Re-wilding beckons landscape architects to embrace a logical next step…to release artistic conceits altogether and replace them with the actual landscape type naturally intended, as much as is realistically possible.

Given the emergence of environmental issues at the scale of the planet, the interests, activities, and design works of landscape architects in the last few decades have evolved. Now, highly designed and artfully conceived landscapes include prosaic elements, such as constructed wetlands, areas for wildlife habitat, plants for pollinators, and features that perform as “living machines”. These new concerns have transformed ordinary elements such as drainage and detention features into performance-driven inventions such as biofilters and bioswales.

Since landscape architecture originates from a long and great history of gardens and artistic conceits made with living materials and natural systems, it’s understandable how the discipline continues to sustain the artful and intellectual dimension of landscape design as the new performance-driven landscapes culturally take hold. In fact, the very definition of a garden is any landscape that is charged with metaphorical meanings and abstractions.

Recent images of environmentally motivated works in landscape architecture that include native grasses, wetlands, and oyster beds to improve water quality, will arrange the elements into artful arrays, dramatic forms, and abstract relationships, as if, when all is taken together, the artistry and compositional relationships remain the priority over environmental performance.

In cases where it is appropriate and environmental performance is the priority, re-wilding compels landscape architecture to move beyond image-driven design for its own sake and embrace the full potential a performative landscape program offers. The three following case studies demonstrate that re-wilding does not present an “either/or” choice. Rather, they are extraordinarily compatible if handled with the right kind of attention.

Re-wilding beckons landscape architects to take the next logical next step in the evolution from highly designed landscapes to ecologically driven solutions. That leap, whether it is a small part of larger design work, or the entire work itself, involves letting go of the artistic conceits altogether and replacing them with the actual landscape that is intended, as much as is realistically possible.

This article examines three re-wilding case studies that all were recently built in metropolitan Dallas. Each case study offers a different approach taken to re-wilding, along with the political and economic methods used to achieve them. Dallas-Fort Worth is a compelling platform for re-wilding because the colossal geography, settled at an average human density of one person per acre, has enabled wildlife to take hold in the undersigned spaces between buildings and throughout the watershed network.

As evidence for wildlife in the city, a recent film by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission, titled Bobcat City, is a documentary about a graduate research program studying urban wildcats in DFW. Red fox, coyotes, turkey flocks, beavers, alligators, and river otters are just a few of the wild species frequently seen in DFW. Cities have always had rats, mice and other parasites that thrive with human urbanism. Wildlife, and the attendant food chains are radical and new phenomena that are distinctly and uniquely the product of the twentieth century and its sprawling and sparse suburban patterns.

DFW is also relevant for the topic and for a broader world audience to consider, because the pattern which formed the metroplex is not unique—it is typical, if not identical, to the patterns that also constitute similar cities such as Atlanta, Las Vegas, and Phoenix, as well as the perimeter regions that flourished around the historical centers of East Coast cities in North America and also in Europe. Coming to terms and contending with the problems in Dallas, offers us lessons and examples that could apply to the same generic patterns throughout the world.

The three case studies examined by this article, all in the Dallas-Fort Worth metropolitan area, are:

- The John Bunker Sands Wetland.

- The Airfield Falls Conservation Park.

- The Trinity River Audubon Center in the Great Trinity Forest.

1. The John Bunker Sands Wetland Center

The development of environmental techniques to re-wild is also producing innovative methods to fund and drive their realization. Located just twenty miles from downtown Dallas, Texas, the 2,000-acre John Bunker Sands Wetland Center (JBS) is a model for taking a problem and combining it with a set of other possibilities that, when taken together, enlarge the outcome and cultural impact of all.

For visitors, the outward image of JBS is a nature project and a constructed wetland for public education and use. Situated within a unique, sinkhole-like basin of approximately 4,000 continuous acres, a single, special-use building receives visitors, offering a set of permanent exhibits, flexible galleries, administrative space and open, programmable rooms that are wrapped with glass and broad shaded verandas. Admission is free, and on days the center is open, visitors savor the exhibits and trails that extend throughout the wetlands over levee paths and walkable wooden trestles.

Without in any way misleading visitors from the enjoyment of their nature outing, the sense of “publicness” that JBS presents conceals the fact it is actually privately owned, as one part of the vast 28,000-acre Rosewood Ranch, a land trust for a significant Texas family. While the idea of shaping public spaces with private hands is not new, it is typically utilized to realize urban parks, cultural institutions, museums, and performance halls, versus as a model for an environmental reconstruction that is publicly accessible. However, there is more to the realization of JBS that makes it an exceptional example of environmental engineering and a model for other places to consider.

For several years prior to the construction of the JBS wetland project, the flat and poorly drained 2,000 acres made the property too wet for agriculture and cattle ranching. Seasonal rains combined with the flat terrain made any kind of land planning and management, unpredictable. Itinerant ponds, potholes, and marshes could appear with seasonal rains to inundate crops. Conversely, in drier years, drought and evaporation turned the network of potholes into a muddy flat that was inaccessible for tractors, trucks, and all-terrain vehicles.

The key that unlocked the potential of JBS, and also solved all the associated land use problems, began with the idea to transform the area into a municipal water storage project for Dallas. By coincidence, the location of JBS is not only close to downtown Dallas, but it is also near a set of regional reservoirs that supply raw water to DFW. Since these reservoirs are also susceptible to drought and unpredictable water levels, JBS stores water that can be transferred to the reservoirs via pipeline to offset the effects of drought.

The environmental engineering that was needed to manage water for the JBS land produced an interconnected system of marshy pools defined by earthen levees. Installing a program of re-wilded wetland plants, a system of trails and trestles for public access, and an iconic visitor center turned what was an otherwise utilitarian water project into a thriving, multi-functional landscape for wildlife and cultural potential.

Educational outreach completes the JBS mission with programs that accommodate visits from elementary schools, wildfowl enthusiasts, birders, and individuals from the city who may simply want a day outing to walk the trail system and appreciate the abundant wildlife. Private groups can also rent JBS for use. During the fall, JBS sponsors a youth duck hunting day that also offers educational seminars in conservation and gun safety.

John Bunker Sands Wetland Center is a model of environmental accomplishment. The clever combination of re-imagining a water conservation strategy, educational outreach, tax abatements, environmental resilience, and making public places with private lands were made cohesive with a re-wilded landscape. Much more can be done with the strategy in other places.

2. The Airfield Falls Conservation Park – Fort Worth, Texas

With any new design movement such as re-wilding, the concept and description have the potential to be misunderstood. Given the great history of landscape architecture as an art and design activity for cultural production, it is understandable that re-wilding could be misunderstood as a renunciation of design and artfulness.

The Airfield Falls Conservation Park in west Fort Worth Texas is one of the newest re-wilding examples which clarifies that architecture and a re-wilded nature can co-exist, not as an option but as a necessity. In this case, the combination and contrast of the two conditions heightens the appreciation and experience of each individually.

During the Cold War, Carswell Air Force Base (AFB) in West Fort Worth, Texas was one of the largest Air Force and military installations for long-range bombing and domestic defense in North America. After the Soviet Union collapsed in 1988, the Defense Base Closure and Realignment Act of 1990 relocated the 7th Bomb Wing from Carswell AFB to Dyess AFB near Abilene, Texas. This resulted in not only a massive downsizing in Carswell’s population but also a significant reduction in size to the airbase geography. Approximately one-fifth of the former area of the base was relinquished to private land speculation. The more modest military outpost that remained is known as the Fort Worth Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base.

In reducing the fenced and secured footprint of the airbase, two regional creeks that were formerly sequestered within the base are now available for public recreation. One of these, Farmers Branch Creek, features a natural set of cantilevering limestone ledges that are the tallest natural waterfall in the north Texas region. Inaccessibility to the waterfall during the Carswell years had made the waterfall somewhat mysterious and legendary in local lore. The project objective was to provide access to the waterfall with a park and trail system. The project purpose was extended by an additional client-driven request to make a state-of-the-art water-conserving landscape.

The Tarrant County Regional Water District (TRWD) under whose jurisdiction the creeks and the parkland are held, wanted the yet-to-be-realized, seventeen-acre “trailhead park” to become the next addition to their vast network of hike and bike trails that already traced other creeks and rivers of their system. The request for a water-conserving landscape would also offer the benefit of introducing park users to water-conserving practices and plant materials that could, by logical extension, eventually reduce demands on the raw water supply as the new lessons circulate throughout the city.

The five-acre area off of Pumphrey Drive in Fort Worth, where park users arrive, coincides with the historic location of the former base commander’s house. All that remains of the commander’s residence are a few foundation walls, the stone curbing of a circle driveway, and a D-shaped concrete terrace that provided a pleasant creek view which was frequently a meeting place to discuss military strategies amongst officers and politicians. The five-acre arrival area also required a program of architectural elements for visitors, set into a re-wilded, water-conserving landscape.

A water-harvesting car park is the first element that visitors encounter. The car park demonstrates two tree and understory examples of how to make shade in paved areas; with tightly spaced live oaks on one side, and a low, non-irrigated gravel paver landscape on the other side. Grading precision directs stormwater into a horsetail reed planted bio-swale and also toward a flume that cascades some of the stormwater into a rain garden pond. Rows of tables that encourage picnics form a line and edge between the car park demo and the open lawn that is planted with Habiturf®, a native grass mix that is the trademark of the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center in Austin, Texas.

Two wings and the tail section of a McDonnell Douglas C-9 Nightingale Transport Jet were donated to the park by the air base for display. Instead of treating the three aircraft pieces like disparate sculptural objects, the design team elected to reassemble them as a dramatic structural tri-pod that forms a gateway arch to the trail system. The 100-foot wide wingspan of the display was also re-wired to illuminate the navigation lights of the wingtips and tail section. Low energy LED lighting extends the conservation lessons of the park, as does a set of night lighting fixtures that are the same as those used by the US Air Force. Both considerations extend the conservation mission of the park and also the history of the site.

Lastly, a shaded family picnic shelter made of powder-coated steel sections re-use the foundation walls of the base commanders house and repurpose the extended patio for park users. All of the architectural objects stand in abject contrast to a natural landscape that is either untouched or enhanced with additional eco-constructing plant species. The use of Habiturf® ties it all together.

The arrival area, containing the display of architectural objects, exits into the second park section; a quarter mile long path, re-wilded with 30,000 pollinator-attracting plants. Once across the existing creek bridge, the six-foot-wide concrete path parallels the creek ensconced by dense tree cover and shade of the creek edge. This “Butterfly Walk” concludes at another bridge over the creek, where the waterfall is reached in a short distance. Nothing at or around the waterfall was touched or modified by the design project.

After testing to confirm the water quality in the creek, the TRWD allows visitors to get into the plunge pools of the waterfall. Children splash and play along with pets that are restrained by a leash.

When experienced, the Airfield Falls Conservation Park offers three sequential landscapes that progress from a re-wilded field with architectural objects, to bio-filtering landscape surfaces, to an untouched and preserved natural waterfall. The image of the front area in particular, with its orange and white, airfield elements and the monumental scale of the historic jet display, is a landscape of mismatched wild and architectural elements.

Bobcats, turkey flocks, foxes, coyote, river otters, and countless avian species have been sited at Airfield Falls Conservation Park. At sundown, when the airfield lights turn on, and the nearby air base broadcasts Taps, visitors note seeing the park mingling wildlife with a re-wilded landscape of nature and architecture. As a case study, the lessons it offers establish an alternative set of possibilities for re-wilding and landscape architecture.

Airfield Falls demonstrates how re-wilding can enlarge the impact of a project done with a modest budget. In lieu of the cost of reworking an entire site with design, the select and strategic introduction of architectural objects transforms the untouched landscape into a perceivable intention. It also demonstrates that re-wilding need not be thought of as a precinct that is two-dimensionally separate from or adjacent to a project context. Instead, Airfield Falls became a re-wilded field condition dotted by highly designed architectural objects. The added coincidence that the re-wilding was agreeable to the existing wildlife already present at the two site creeks confirmed the appropriateness of the idea and also served as a lesson for similar circumstances.

3. The Dallas Trinity River Audubon Center (TRAC)

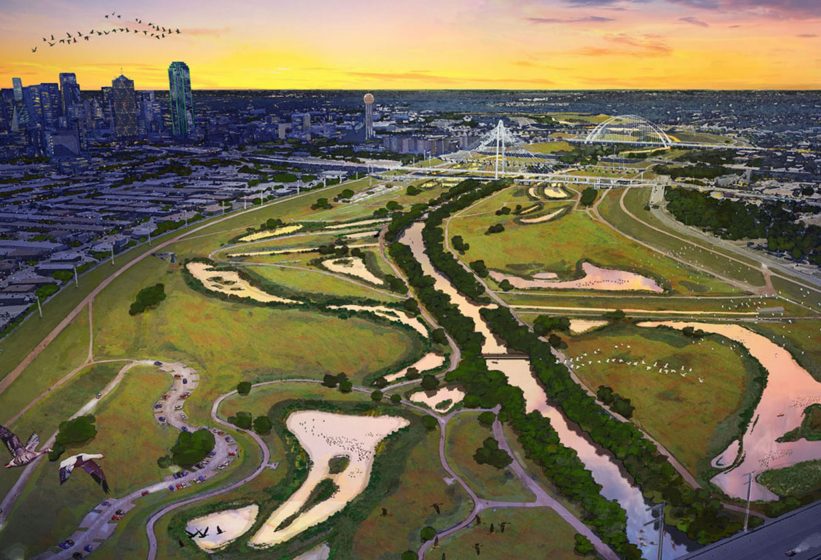

Dedicated in 2008, the Dallas Trinity River Audubon Center sits on 120-acres of reclaimed land and illegal dump-site that exist within the vast, 10,000-acre Trinity River Floodway corridor. Located safely above the inundation line of the Trinity River flood management corridor, the Center exists between a climax community of riparian trees and hardwoods known as The Trinity River Forest to the south and an eight-mile, levee-protected and grassed conveyance area to the north.

The location of TRAC near the threshold where the grassy conveyance transitions to the forest, anticipates a forty-year-long desire by patrons and stakeholders in Dallas to realize the entire 10,000-acre corridor as a publicly accessible urban park. Over four decades, nine distinct plans have been developed by acclaimed and internationally renowned landscape architects. While a recent plan by MVVA is proposed for the area between the two new highway bridges by Spanish architect, Santiago Calatrava, no federally approved plan, nor a means to fund another one, currently exists.

The Trinity River Center epitomizes and embodies the national mission of The Audubon Society: what is good for birds is good for everyone. TRAC was specifically developed to fulfill two purposes: “the production of habitat for indigenous and migratory birds”, and to “serve as a place that will form a nature connection between visitors and the environment”. Education is the common product of both goals, since “people don’t tend to care about things they don’t understand”, notes Lucy Hale, the current director. The more people who understand how songbirds are the coal mine canaries of the environment, the more they can appreciate the critical role of nature, the environment, and their relationship to both.

While the architecture at TRAC is charged with abstractions, dramatic cantilevers, and poetic meanings, the re-wilded landscape around it is pure prose. Consisting of seven miles of publicly accessible paths, dotted with blackland prairie potholes, the re-wilded landscape has produced a compelling reason for its existence.

The Dallas Trinity River Audubon Center is a textbook example of twentieth-century writer Sigfried Gideon’s notion of “the machine in the garden”. But where Gideon’s twentieth-century machine suggests a highly designed garden that is human-made, re-wilding offers a new kind of garden that is wild. Such a contrast, taken to a practical and poetic conclusion, heightens the potential and experience of both.

Summary

A re-wilded landscape can offer an experience of beautiful wildflowers, song birds, and fall color. But they can also include encounters with poisonous snakes, wildcats, undesirable plants, and other species who are unhesitant to defend themselves during face-to-face encounters with people. Even the seemingly bucolic and shaded environment of the Great Trinity River Forest has inadvertently drowned fishermen caught and overwhelmed by floodwaters from a deluge that occurred far upstream.

The realities of a re-wilded landscape demand that individuals set aside the distractions of cell phones and their ubiquitous internet access, which allow individuals the privilege of moving through environments while unaware of their surroundings.

In this respect, re-wilding begins to strike a philosophical chord. For humanity to sustain a beneficial relationship with the environment and planet, Nature and how people relate to it, cannot be ignored. Perhaps it is this attribute which best recommends re-wilding as a new and conscious objective for cities.

Kevin Sloan

Dallas-Fort Worth

Leave a Reply