Part one: natural potential from mega math

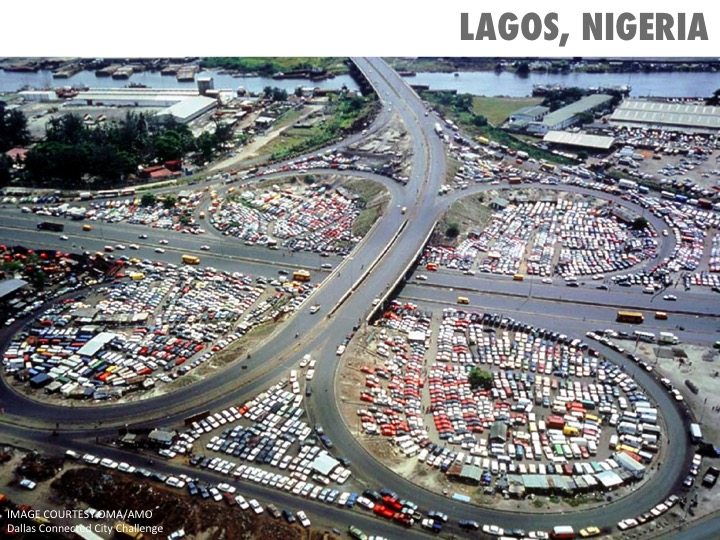

Never before on the Earth or in the entire history of the human condition has something like a megacity been possible, until Tokyo and Mexico City appeared in 1950. Typically defined as a metropolis with 10 million residents or more, projections by the 2009 Edition of UN World Urbanization Prospects suggest there could be as many as thirty megacities by 2025. Over half the world’s population is living in cities and megapolitan regions according to the UN Edition of 2010. As populations migrated from rural areas to cities, megacities and mega regions became more powerful and influential than the nations and countries they inhabit. For instance, the international influence of Malaysia lies in the great commercial hubs of Singapore and Kuala Lumpur.

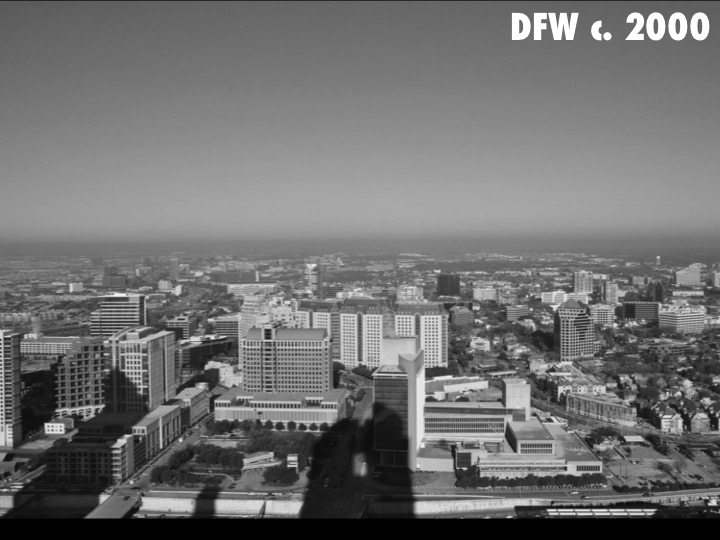

The Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex (an urban agglomeration referred to as DFW) is becoming a megacity. While New York City, Hong Kong or Shanghai are delirious concentrations of skyscrapers, DFW is a textbook example of a twentieth century city of nodes in an agglomeration that is almost entirely suburban. In downtown Dallas and Fort Worth, originally two separate cities, the nodes are building clusters. Once freestanding courthouse towns and county seats, the downtowns now exist as bi-nuclear centers in a vast and sparse geography. Other nodes have formed around cloverleaves and in the former town centers and municipalities that were assimilated by the mega growth.

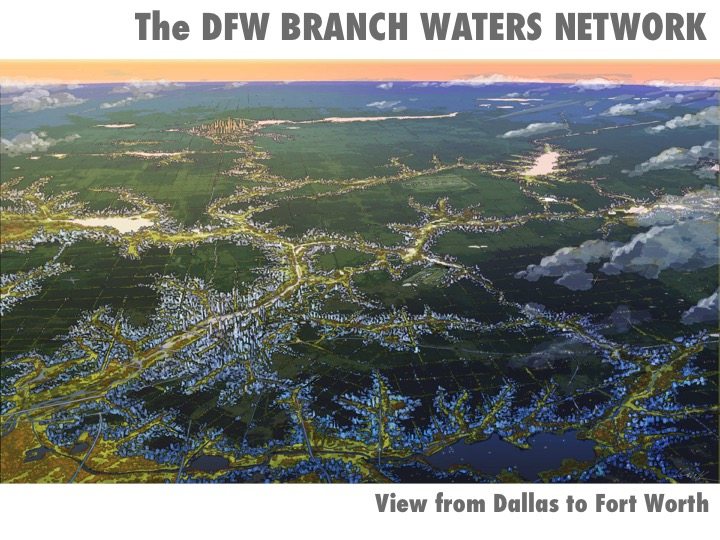

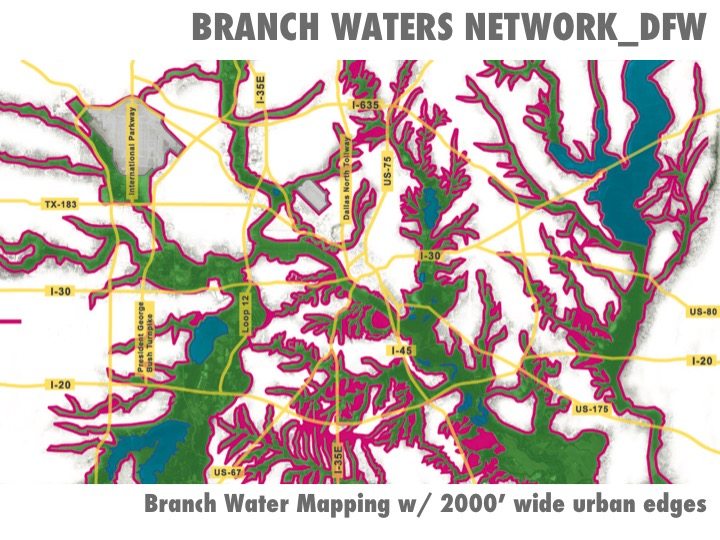

The Branch Waters Network is a concept to use the entire waterway system in metropolitan Dallas–Fort Worth as an attraction to structure a metropolitan urbanism.

The net effect of seventy years of market-driven proliferation is a city that is dominated by shapeless open space and experienced periscopically, through the windshields of cars. Of greater concern is the fact that DFW, and other suburban megacities like it in North America, are statistically impossible to densify.

DFW is the fourth largest metropolitan region in the United States with a population of 6,450,000 residents settled on 5,950,000 acres of incorporated infrastructure. In order to preserve the economic investment of the entire infrastructure by increasing the average density of 1.1 persons per acre to match the 5.5 person per acre density of Portland, Oregon, it would take more than the population of Canada—(5.5 x 6 million approximate acres = 33 million people )—to settle the new, denser, urban footprint. The future of cities—such as Los Angeles, Phoenix, Houston and Atlanta—that generally share the same pattern, density, and math, is potentially vulnerable to social, economic and environmental problems that could particularly affect the areas that are thinly settled.

Architecture and planning are generally without tested theoretical models to retroactively reconfigure vast urban geographies. Daniel Burnham’s overused imprecation to “Make no small plans” sidesteps a stupefying problem, namely that any “big plan” for a mega region will have to criss-cross municipalities, established communities and political structures, none of which are equipped to sustain complex projects that could take decades.

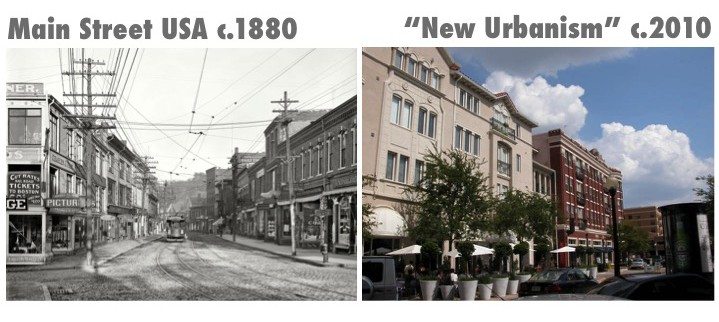

Moreover, planning as a potential solution quickly descends into a conundrum, considering that the great planning models and pattern books of the 19th century arose to develop cities and an urban form, not to retrofit vast geographies where the land is already atomized into private ownership and sliced apart by a fully realized infrastructure. The so-called New Urbanism, while honorable in intention, attached its sympathies to the myth of the small town and a nostalgic association with traditional architecture. America has not been a network of small towns since the 1800s.

During a March 2013 lecture at the Dallas Museum of Art, Professor Kenneth Frampton of Columbia University poignantly recalled a phrase that someone had written onto a rendering of a 1950s utopian city while it was on display at the New York Museum of Modern Art in the late 1980s.

“There are no cities anymore.

We are incapable of making cities anymore.

The machine is incapable of making cities anymore.

We’ll have to get used to living in the jungle.”

—Unknown

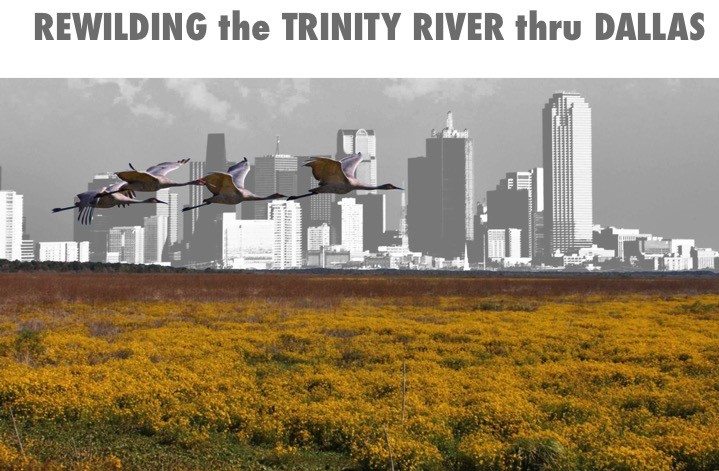

The image of a jungle city—a confused and chaotic mechanical landscape—is provocative and dramatic. Short of accepting that a blighted “jungle” of abandoned and depopulated geographies is statistically pre-ordained for the future of a suburban megacity, perhaps Frampton’s use of the word “jungle” isn’t only a metaphor, but rather a clue that the landscape and natural waterway network of a city could inform and drive an urban solution.

Where planning or pie-in-the-sky abstractions might present a challenge to the rugged individualism of American culture, the same culture seems to understand and generally appreciate nature and the value that it offers—qualitatively and economically. In lieu of conventional notions for planning, it may be more possible to develop a strategy—a game of nature driven rules for individual projects—that, taken together, could lead sprawling populations toward an orderly rearrangement and a new and unprecedented urban form that is connected by a living fabric.

Part two: the Dallas-Fort Worth Branch Waters Network

The Branch Waters Network is a concept to use the entire waterway system in metropolitan Dallas–Fort Worth as an attraction to structure a metropolitan urbanism.

Seizing upon the familiarity of nature and how North American culture typically assigns value to it, the ribbon like strands of shade, water and continuity of the DFW system, have the capacity to retroactively re-form a future urbanism into living filaments that attract density, transit systems and reconstituted ecological systems. Segments of the DFW Branch Waters Network are already complete.

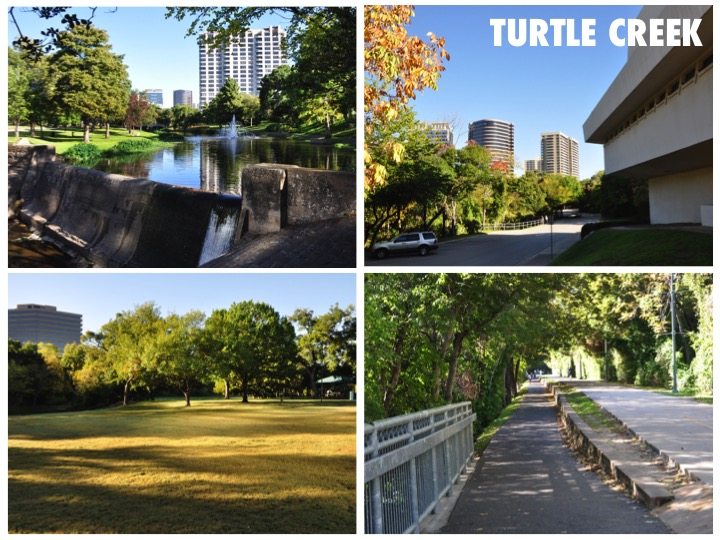

The seven-mile long Turtle Creek corridor in Dallas is the only part of a 1912 comprehensive plan prepared by George Edward Kessler, a German-born education planner. Kessler’s vision transformed an otherwise featureless ravine into a city walk for education in art, architecture, history, nature and citizenship, by adding a set of parks, sports fields and passive activities to the linear corridor, as well as a chain of lakes, weirs, trails and bridges. Turtle Creek Boulevard ties it all together.

From 1950 to 1980, the location and natural beauty of Turtle Creek gave rise to several condominium towers along the edges as well as a theater designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. As evidence and a demonstration of the urbanizing potential of nature, the concentration of civility and density along Turtle Creek is an exception to the cultural raison d’être in Texas, that luxury and the good life typically means an estate lot or a sprawling Southfork-like ranch. Considering that DFW is on the same latitude as North Africa and frequently one of the hottest places in the U.S. during summer, the 100-year old example of Turtle Creek is a model for a landscape-driven DFW and a useful case study for other metropolitan cities.

Contemporary with Kessler’s Dallas Plan, the 1911 construction of a lake and park on White Rock Creek in East Dallas produced DFW’s closest example of an Olmstedian park. White Rock Lake is a 1,200-acre reservoir set within a 1,600-acre public park that includes the Dallas Arboretum, two boating and sailing marinas, passive recreation areas and the Boathouse Cultural Center, circumnavigated by a continuous bike and pedestrian trail and the continuous tree cover of White Rock Lake Park extending to the Trinity, which is the river that established Dallas and Fort Worth.

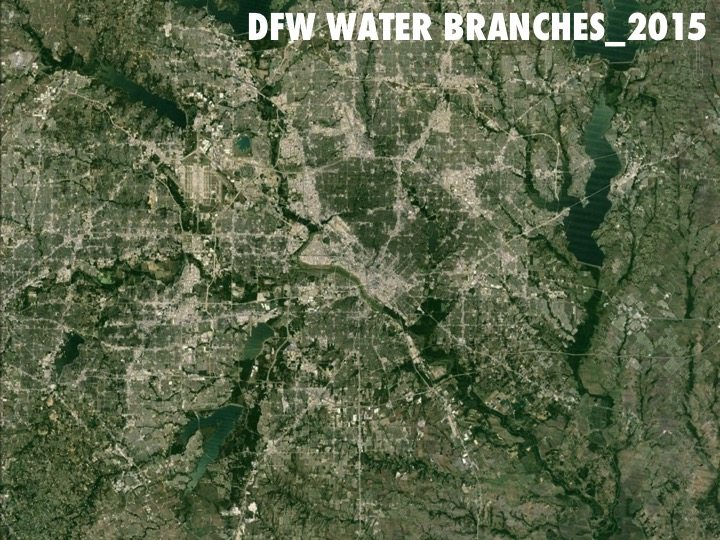

When observed in satellite view, the waterway branches of forested creeks, ravines and rivers within the metropolitan area look like the veins of a leaf or a colossal tree that has been flattened and espaliered onto the Blackland Prairie. The water branches traverse an urban geography that is 60 to 70 miles wide east to west, 40 to 50 miles wide north to south.

When the most obvious branches are mapped, there are over 300 potential miles of water branches that would double the real estate value along each side, considering each branch has two outside edges. In Dallas County alone—which is one of eleven that comprise the DFW metropolitan area—over 90 percent of the natural drainageways are intact and unimproved.

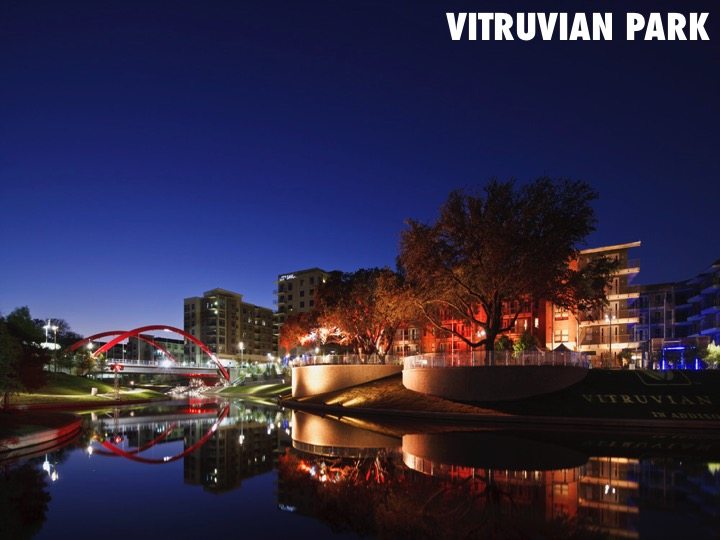

Vitruvian Park in North Dallas (Addison) configures a high-density mixed-use urban enclave on 112-acres that is organized by a 17-acre spring fed park. Completed in 2008 and master planned by my studio, Kevin Sloan Studio, the urban blocks of the five and 11-story fabric present a conventional street wall urbanism to the avenues and a contrasting, modernist repetition of residential wings to the park so that the outdoor courtyards between seamlessly key into the preserved vegetation of the public park.

The seventeen-acre park, also designed by Kevin Sloan Studio, is fed by Farmers Branch Creek, which is also part of a vast network of sheet springs that exist throughout the Blackland Prairie region. In lieu of the dramatic artesian springs of the Texas Hill country near Austin, North Texas springs move slowly and laterally over a continuous limestone shelf until the erosion of a ravine daylights and receives the water.

In order to raise the southeast corner of the master plan out of the flood plain, the excavation at Vitruvian Park was a logical extension of a natural process of day-lighting the sheet flow for an urban park that would naturally gather density. Vitruvian Park also demonstrates that nature and landscape are effective tools that can overcome suburban suspicions of density by offering an urban-like enclave that isn’t in a downtown center.

For enthusiasts of modern architecture, the Dallas Urban Reserve is an example that combines water branch urbanism with low impact development to form a residential enclave of 50 lots. Urban Edge Developers in Dallas funded and developed the project on a 12-acre site that was abused for 55 years as an illegal landfill, as contractors opportunistically dumped Sheetrock, pipe, shingles and other debris in creating what amounted to an industrial earthwork.

Although houses by Tod Williams and Billie Tsien have been constructed and others by Hanrahan Meyers Architects of New York and Kieran Timberlake of Philadelphia were proposed, the subdivision is prevented from dissolving into an architectural expo because of the vigorous and visually cohesive landscape of a continuous bio-filtration street. Sloping asymmetrically to convey storm water into a system of repetitive filtration beds planted with bald cypress, pond cypress and horsetail reeds, a single two-way street connects an existing 1950s subdivision at the entrance into an existing water branch that is White Rock Creek Greenway.

The project was awarded a 2011 ASLA Award of Excellence and has been nationally and internationally recognized by journals such as Topos and Eco-Structure. Kevin Sloan Studio conceptualized the bio-filtration street, designed the landscape architecture and collaborated on the development planning with DSGN Architects of Dallas.

Green ribbon urbanism

Nested along any branch waterway, mixed-use edges and building enclaves would offer the forest and nature on one side and the civility of streets, squares, and neighborhoods on the other. Turtle Creek and the addition of the Katy Trail in the last fifteen years—a rail-to-trail conversion into a shaded promenade—are contemporary examples that further support the urban potential of building the entire drainage network in DFW into an urban system.

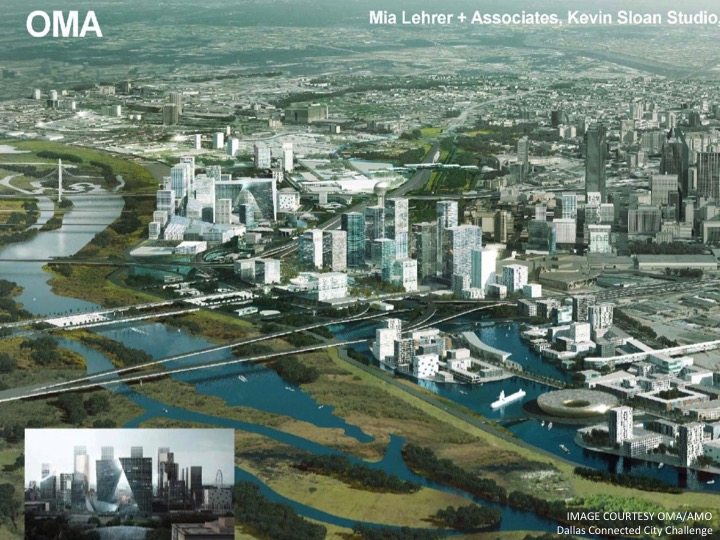

While other projects throughout DFW are currently in development along various sections and unrelated segments of the metropolitan branch waters, they are typically seen as railway conversions into hike and bike trails, or as stand alone mega-visions such as the great Trinity River projects in the downtown environs of Fort Worth and Dallas.

No larger vision yet exists to see the common thread of all of these separate projects as stepping-stones that could produce a new and unprecedented ribbon-like urbanism tracing the shaded and continuous corridors. Considering how the sprawling low density urbanism of DFW is typical to North American cities and the perimeter rings of European and Asian centers, the Branch Water network could also be seen as a paradigm and potentially a palliative to provide connection, cohesion and a memorable character to a largely generic pattern.

Branch variety

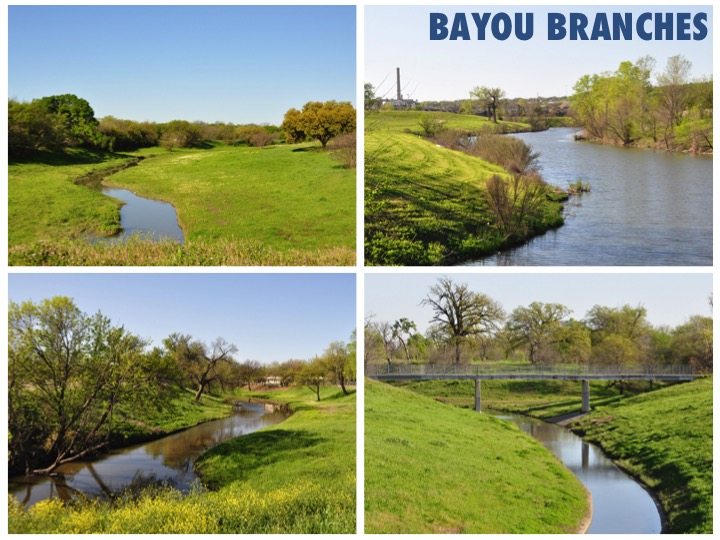

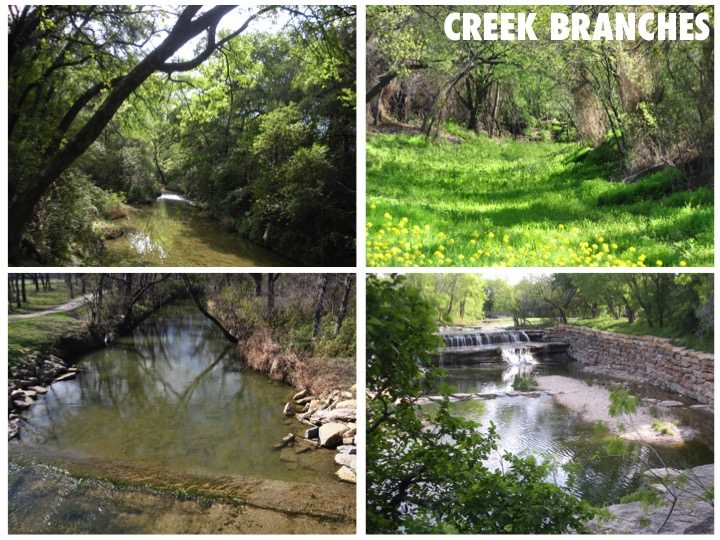

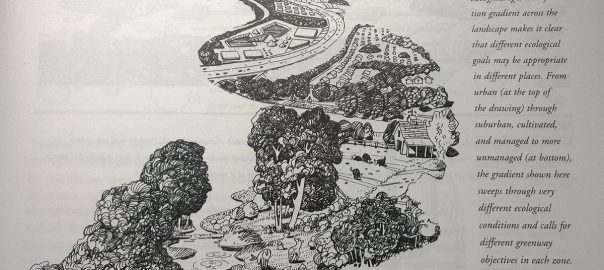

The Branch Waters concept does not presume that the English landscape of fine lawns, azaleas and towers of Turtle Creek should proliferate throughout the entire DFW drainage network. The existing characteristics of the riverines and their potential are as numerous and varied as are the landscape types that could be added. Ultimately, communities along the network should develop a program that fits the distinctive needs of their respective branch.

In the lowest and flattest geography of the waterway system, fragments of the former Trinity River in Dallas, known as The Meanders, now operate as flood sumps. In their current condition, they are more akin to the static waters of a bayou than a creek with a current. A project known as the Trinity Strand has taken steps to add a pedestrian and bike trail above the high water mark of a particular piece that courses through the Dallas Design District.

Creeks and ravines that slope to the natural Trinity floodplain often convey a brook-like flow of water that, over eons, has cut ravines through the soft limestone and caliche geology. Many of them are sheet springs and numerous street names are clues, such as Kidd Springs, Spring Valley, and Marsh Lane. Most are protected by the Army Corps of Engineers, but the third branch category typically cradles an ecology of hardwoods that established over time in the deep topsoil that accumulated in a valley or ravine. Many of these exist along the West Dallas escarpment or in north and south Oak Cliff and seasonal rains create intermittent flows.

Circumventing red tape

In addition to the cultural, environmental and economic merits of the concept, the Branch Waters has a built-in potential to avoid problems and bureaucratic red tape that often stymies typical plans and/or grand urban visions.

Given how the waterway system in DFW is largely intact and continuous—as it typically is in most cities—no additional land acquisitions, eminent domain takings, bond programs, or the usual gauntlet of political approvals are needed to incrementally accomplish the urbanism, one project at a time. Rather, it might only need a simple set of guidelines to construct spatial relationships between the new urbanism and any water branch.

Summary: resilience or irrelevance

The Branch Waters Network also has the potential to address two significant economic and environmental questions that Dallas-Fort Worth and other Endless cities are facing, especially in the U.S. Southwest. “World leaders now understand that the future of any nation will be disproportionately delivered by megacities and metropolitan regions,” notes Bruce Katz, economist and geostrategist with the Brookings Institute. In order to sustain their relevance on the world stage, any metro must attract talent, retain talent, generate and export their own unique economy, and flourish into a culture that can compete with other world cities. Where baby boomers would move to a city after getting a job, millenials and Gen-X generations do the opposite—they move to a cities that offer walkability, parks, nature and a quality of life they desire, then they find a job.

In so-called “business-friendly” cities, such as Dallas-Fort Worth, Phoenix, Houston and Atlanta, that offer income potential and tax incentives, the sprawling geography was constructed in haste and left out the kind of urban, environmental and cultural qualities that are now a first priority for individuals, families and even corporations.

After a highly publicized national competition, the Boeing Company elected to relocate their Seattle corporate offices to Chicago in 2001, alluding to Dallas-Fort Worths’s “lack of cultural amenities.” The sting of the loss set into motion an array of civic project that included the Wyly Multi-form theater by OMA, The Winspear Opera by Foster & Partners, the City Theater by SOM, an addition to the Booker T. Washington Arts Magnate School by Allied Works, and a downtown parks master plan by Margreaves and Associates in 2003 that identified 19 park sites in downtown. The Branch Waters Network can be seen as a logical extension of the downtown projects applied to the entire geography of Dallas-Fort Worth that would develop a more appealing urban form by drawing new urban densities to the edges of the metropolitan waterway network.

The environmental questions may be even more stupefying. Studies issued in February 2015 by Cornell and Columbia Universities aligned with other environmental studies that indicate a 50 to 80 percent chance that Texas and the American Southwest may experience a 35-year long drought—a mega-drought—sometime before 2100. Such an event would be catastrophic to DFW or any metro, potentially forcing the de-population of the city, the abandonment of entire parts of the city, public parks and certainly any irrigated landscape or use in order to conserve water.

The existing natural waterway system in DFW is where the region’s longevity might be secured. It is where the mature trees, water and any environmental quality currently exist. Gathering urbanism along the edges of the network would anticipate the mega-drought and forestall the potential for individuals and companies to flee the metropolitan area, while also generating an orderly rearrangement of the unsustainably suburban pattern into a form that would be more resistant to calamities and natural disasters.

The potential for a mega-drought and the eye opening realization that the generic pattern cannot be statistically urbanized potentially belies a much larger economic rationale to support the formation of the Branch Waters Network in DFW and other cities where a similar natural system exists.

World and national leaders understand that megacities and metropolitan regions will disproportionately deliver the future for any nation. For metros to be relevant and competitive on the world stage, they must retain talent, attract new talent, generate and export their own unique economic production, and flourish into a culture that can compete successfully, in both domestic and world markets.

Every city currently competing on the world stage has one or more features that cannot be copied by another metro. By logical extension, the qualities of a city are now part of a broader strategy for a megacity or region to remain relevant on the world stage. The Branch Waters Network and the ribbon-like urbanism it could form may be the physical, spatial and environmental distinction Dallas-Fort Worth needs to endure.

Kevin Sloan

Dallas-Fort Worth

Leave a Reply