An image of expanding cities is associated, in most people’s minds, with the shrinking and gradual disappearance of urban nature.

The revalorization of urban nature is both an incipient opportunity for change and a potential recipe for disaster.

The importance of urban nature is begin redefined with new values: of recreation, relaxation and, ultimately, of possession—private ownership and possession, that is—finding expression in diverse forms.

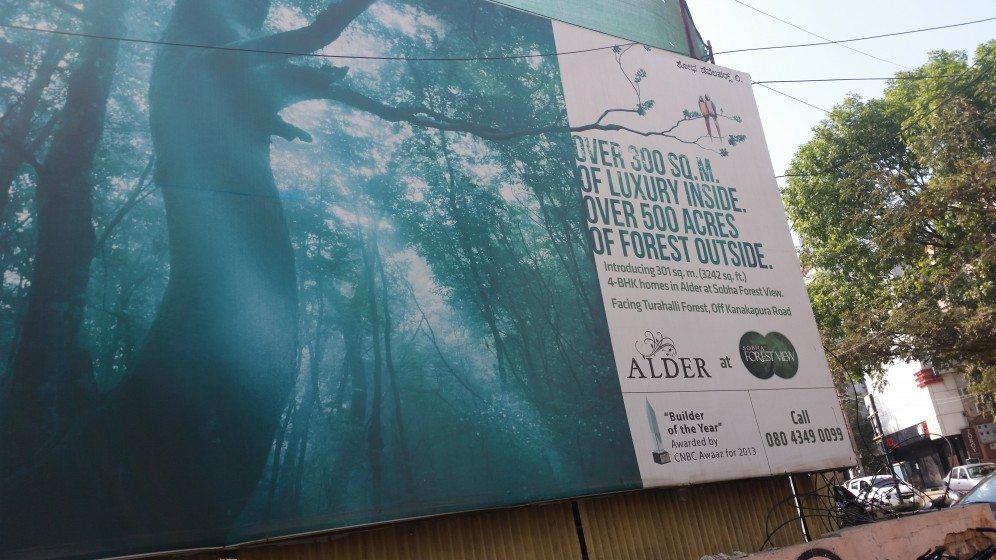

Advertisements for real estate developments are a hotspot for the revalorization of urban nature. A quick look at the urban visual landscape of Bangalore—at the eye level of what used to be the treeline, dominated by majestic avenue trees—shows a vast expanse of real estate advertising, much of which is targeted at the wealthy, advertising the sale of apartments and homes that range anywhere from $US 200,000 to over a million dollars.

Advertisements for real estate developments are a hotspot for the revalorization of urban nature. A quick look at the urban visual landscape of Bangalore—at the eye level of what used to be the treeline, dominated by majestic avenue trees—shows a vast expanse of real estate advertising, much of which is targeted at the wealthy, advertising the sale of apartments and homes that range anywhere from $US 200,000 to over a million dollars.

To differentiate themselves, many projects identify themselves as “green” by using terms such as “pristine,” “lake,” “green” and “woods” prominently, and somewhat indiscriminately. For instance, just next to Bangalore’s extremely polluted Bellandur lake, an advertisement for an apartment complex “iWoods” stands out, somewhat bizarrely juxtaposed with a view of toxic foam overflowing from the lake. Another developer advertises “luxury lake-front green homes” that are “pristine” located near the same polluted lake. The irony of the situation should be obvious, yet these homes sell fast and appreciate in price.

Living near a well-maintained lake is a luxury for any urban resident. The Kaikondrahalli lake, an oft-cited example of a community-restored and managed lake in Bangalore, organizes an annual lake festival attended by thousands, with children using leaves, flowers and stone art to decorate the area. They enjoy the now unusual experience of observing and listening to the calls of a lake brimming over with coots, moorhens and ducks.

Living near a well-maintained lake is a luxury for any urban resident. The Kaikondrahalli lake, an oft-cited example of a community-restored and managed lake in Bangalore, organizes an annual lake festival attended by thousands, with children using leaves, flowers and stone art to decorate the area. They enjoy the now unusual experience of observing and listening to the calls of a lake brimming over with coots, moorhens and ducks.

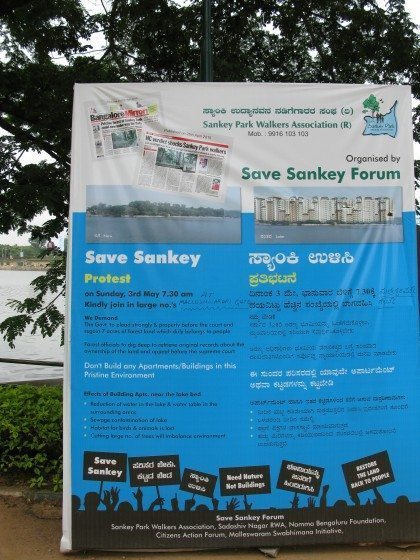

Other lakes, such as the Sankey Lake, promote outdoor exercise with special equipment for senior citizens. Yet the biodiversity and ecological quality of these lakes, which are actively maintained by groups of local residents, are being threatened today by construction in adjacent, ecologically sensitive floodplains and forest reserves. This presents a truly ironic situation: the same construction industry that packages and advertises the presence of urban nature as a resource to be enjoyed by their future residents contributes heavily to the dwindling and disappearance of these resources.

A further step along the evolution of this new urban aesthetic is the complete repackaging of urban nature as a private resource. Thus, new residential communities advertise private butterfly gardens, private streams and even private lakes. Others advertise the exclusivity of locations adjacent to forest reserves. Some claims are frankly bizarre, such as an advertisement that describes an idyllic environment where trees are so happy, “their roots don’t touch the ground.” Readers of these advertisements, meanwhile, are left wondering if the people who create these advertisements have had much practical experience with planting and maintaining trees.

Some would argue that the revalorization of urban nature is a good thing, and perhaps it is, in part. Certainly, if compared to the city aesthetic that the above advertisement portrays, of a baby seeking to live close to shopping malls, I think one can safely assume that we need a renewed public conversation about the importance of nature in cities. I cannot think of an actual baby who would be happier if taken shopping rather than on a lakeside stroll. I would also hope that it is obvious why access to lakes is more important for the well-being of cities and city residents, compared to shopping malls. But the devil is in the details. Who owns this nature? Whose needs does it serve? And will the advertisers who benefit from the real estate value of access to urban nature actually join forces to protect and restore urban ecosystems as public goods?

One path forward, proposed by some planners in Bangalore, is to add a “green tax” to high income residences located around lakes, forest reserves and other public urban ecosystems, ensuring that real estate development contributes to a fund for ecosystem protection. We need a sustained conversation to discuss the feasibility of such measures, looking at the experiences of other cities.

The revalorization of urban nature presents both an incipient opportunity for change and a potential recipe for disaster. We need a renewed, public discussion about these values, even as our developing urban aesthetic needs a ‘reset and reboot’.

Harini Nagendra

Bangalore

Leave a Reply