In November 2016 there was a celebration in London: it had been 40 years since the idea of creating an Ecology Park in central London was first suggested. The event provided opportunities to share memories of those early days and to see how the concept has taken root and proliferated. We met near Tower Bridge on the site of the original park and walked from there along the south bank of the Thames to the redeveloped docklands of Rotherhithe, ending up at Russia Dock Wood and Stave Hill Ecology Park. There was much for us all to learn.

We need to learn from our great successes and ensure that their legacy survives.

The Walk had been suggested by a team who are currently investigating the historical development of ecology parks in this part of London, and I was struck by the fact that most of the people who attended were too young to have known how it all started. It seemed that knowledge of the first ecology park and its achievements had already been lost in the mists of time. It certainly wasn’t history to me, as I had been closely involved, but it made me realise how quickly a body of knowledge can be lost between two generations.

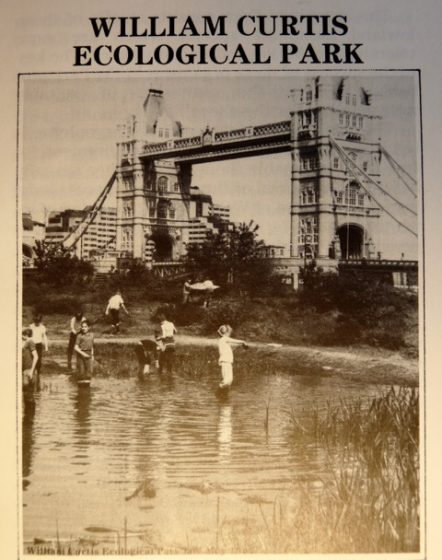

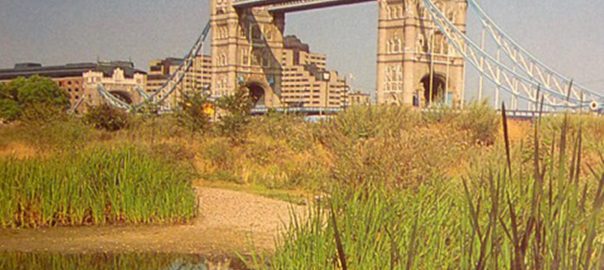

I told the story: how Max Nicholson, who was one of the most influential conservationists in the U.K., persuaded the Queen’s Silver Jubilee Committee that they should create an Ecology Park as part of the celebrations to be held in 1977. His idea was to convert an unsightly patch of derelict land on the south bank of the Thames next to Tower Bridge into a mixture of natural habitats that could be used for environmental education by local schools. I suspect that few of the committee members had the slightest notion of what he had in mind. It was completely novel. But it fitted their aims, which were to improve the landscape along the proposed route of the Silver Jubilee Walkway being planned along South Bank from Westminster to Tower Bridge. Not only would the project remove an eyesore, but it was argued that an ecology park could be created quickly and at a fraction of the cost of conventional landscaping. Given the constraints of timescale and available funding, the committee quickly agreed. The result was that two acres of derelict land were made available on a short-term lease, on the understanding that the park would eventually close when planned development went ahead. The committee also provided the modest sum of £4,000 towards the cost of creating new ecological habitats.

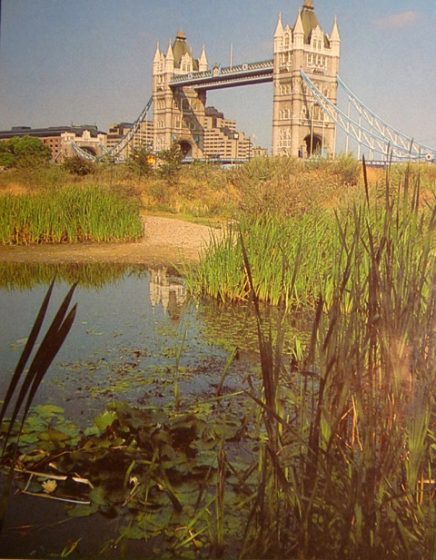

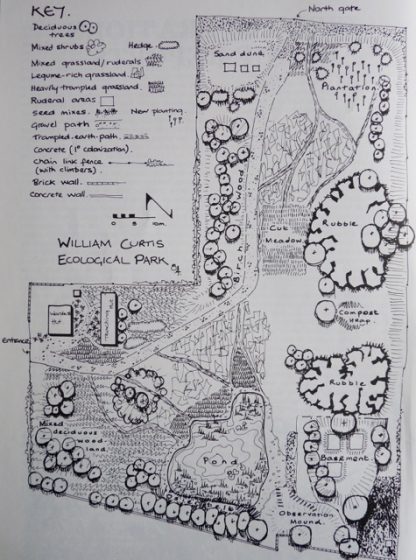

Where did the idea for an ecology park come from? I think it likely that Max Nicholson’s proposal was influenced by the work of Lyndis Cole, one of his staff at Land Use Consultants. She had just written an article in Landscape Design describing Dutch techniques for the creation of naturalistic plant communities in urban areas. She was a real pioneer and it was no surprise when she was given the job of creating the new ecology park at Tower Bridge. Her plan, drawn up in November 1976, indicated the range of habitats to be created, including a small meadow, mixed woodland, willow carr, and a shallow pool. These habitats were inspired by the natural parks known as Heemparks, which had become well established in towns and cities in the Netherlands, where they provided opportunities for inner-city children to have contact with nature.

The new park at Tower Bridge opened in time for the Queen’s Jubilee celebrations in May 1977. It was called the William Curtis Ecological Park, named after the eighteenth century botanist who produced the first flora of London–possibly the first publication to be devoted to urban nature. William Curtis Park was to become another pioneer. Its success took everyone by surprise. Commentators in the media could not believe that such an apparently natural environment could be created so quickly on the rubble of derelict warehouses.

The park was also an immediate success with local schools. It was booked solidly for classes through every term. Two teachers were appointed, one for younger children and the other for teenagers. They were learning fast on the job, developing teaching aids that were related specifically to the urban environment. The rate of colonisation by plants and “mini-beasts” exceeded all expectations, and this provided a wealth of material for detailed studies of urban ecology. The increasing diversity of butterfly species from six to 21 over seven years was particularly dramatic. It demonstrated very clearly what is possible in the middle of a large city.

The William Curtis Ecological Park closed in 1985 to make way for new developments. During its short life, it had over 100,000 visits from local schoolchildren. It provided a link with the natural world that was a new experience for these inner-city children. For some, it was a place they will remember all their lives. But the park left another legacy that persists. It paved the way for other, more permanent ecology parks in the new development zones along the Thames and in the redundant docklands. In the mid-1980s, the charitable trust that ran William Curtis Park rebranded itself as the Trust for Urban Ecology to promote these and a host of wider initiatives. Some of the ecology parks created at that time still exist today. One of these is Stave Hill in the old docklands of Rotherhithe.

So we return to our celebration, for it is 30 years since Stave Hill was constructed, and we wanted to see how it has fared. We walked through the new residential district, along canals and waterways with bridges and bollards dating from the time when this was a hive of maritime activity. Russia Dock, where the ships brought timber from Siberia, is no more. It was filled in and planted with native trees in the 1980s to form Russia Dock Wood, part of the ecological landscape that has become so characteristic of Rotherhithe. We arrived at Stave Hill to find the Trust for Urban Ecology (now part of Conservation Volunteers) still going strong. The trees have grown and matured since I was last there in the 80s, but the vision is the same.

There has been great continuity at Stave Hill. Rebeka Clark has been working there since 1989 and still runs things today. She points out that everyone has gained from the far-sighted vision established in the early years at William Curtis Park. I am glad to hear that those words are not forgotten. As well as all the structured educational visits to Stave Hill, there is a more informal monthly children’s club, Kids@StaveHill, and a program of volunteer days for local people on Wednesdays and Saturdays. The park also provides opportunities for corporate teams from banks and investment companies to gain experience in environmental projects. These volunteers find themselves building bat boxes or constructing bee walls, as well as doing their fair share of habitat management in the wetlands and woodland. Their contribution amounts to over 700 days of work every year.

The park also benefits from people undertaking community service. Others use the park to complete their John Muir awards. Every year, in May, local residents are invited to join a dawn chorus walk. This year, they were treated to a great surprise: the song of a grasshopper warbler coming from the reed bed at Lavender Pond nature area. A wetland warbler in the middle of a housing scheme!

The ecology park still seems to get by on a shoestring budget, but what impressed me was the way it is supported by the community. People here know what ecology means. They have lived next to an ecology park for 30 years. Their children have come here from school and many residents have volunteered to help. The park is part of the community. For many of these people, knowledge of kingfishers, cormorants, hedgehogs, and herons is part of life.

From those small beginnings near Tower Bridge, a new philosophy has taken root. Stave Hill is not alone. Camley Street Natural Park, created in the 1980s on a disused coal yard at King’s Cross, has become one of the most successful nature parks in the U.K. and is a showcase for the London Wildlife Trust. Another is the Greenwich Peninsula Ecology Park, a four-acre wetland along the banks of the Thames constructed in the late 1990s as part of a major housing scheme and managed by Conservation Volunteers (which has now absorbed the Trust for Urban Ecology). The project officer, Tony Day, tells me that the vision created by the William Curtis Park is still firmly with them at Greenwich Peninsula Ecology Park. Last year, the park had 12,000 visitors and a host of activities, including 48 school visits involving 1,200 schoolchildren. They also had six work experience placements and provided material for 27 higher education projects in Environmental Management, Product Design, and Landscape Architecture.

These are places created specifically for nature to thrive in the city. They are places where local people, and particularly children, can relate to the natural world. We need more of them.

But we also need to retain the knowledge and experience gained in these endeavours.

The legacy of the early days of ecological parks in London still exists in written records, especially in the annual reports of the William Curtis Ecological Park and the Ecological Parks Trust, together with its successor, the Trust for Urban Ecology. They contain much information about the projects carried out as part of the educational programmes, together with detailed accounts of the monitoring of ecological changes. This is valuable material that needs to be more readily available. I am glad to hear that the team investigating the history is intending to digitise these archives. But there are other records, too, in the form of published papers and books by some of the people involved. We need to ensure that practitioners today do not lose sight of these sources.

David Goode

London

***

Here are just a few of the key items that tell the story in more detail:

Cole, L. & Keen, C. (1976) Dutch techniques for the establishment of natural plant communities in urban areas. Landscape Design 116, 31-34.

Lyndis Cole. 1986. Urban opportunities for a more natural approach. In: Ecology and Design in Landscape. Bradshaw et.al. Eds. Blackwell Oxford.

Jeremy Cotton. 1982. The field teaching of ecology in central London – The William Curtis Ecological Park 1977-80. In Bornkamm et. al. Eds. Urban Ecology Blackwell Oxford.

Malcolm Emery. 1986. Promoting Nature in Cities and Towns: a practical guide. Croom Helm and Ecological Parks Trust.

David Goode. 1986. Wild in London. Michael Joseph (see pages 179-181).

David Goode. 1989. Urban Nature Conservation in Britain. Journal of Applied Ecology 26, 859-873.

David Goode. 2014. Nature in Towns and Cities. Collins. (see pages 318-9).

David Nicholson-Lord. 1987. The Greening of the Cities. Routledge (see pages 120-122).

Leave a Reply