Why do we plant what we do in our personal gardens? It turns out it’s driven by a complicated mix of personal philosophy and social posturing, which sometimes are at odds. And, it turns out, in South Africa and many other countries, we don’t even plant our own gardens. This is done by “unskilled” and immigrant laborers. We talk a lot about gardens in the nature of cities, but what of gardeners, especially as part of the labor force?

In South Africa, most middle class homes will have a gardener. Gardeners in this country are nearly always men and, reflecting the apartheid history of our country, are nearly always black. Gardeners are generally paid as unskilled labor at shockingly low rates. Shamefully, gardeners in South Africa are still often referred to as garden ‘boys’. One can only speculate that making grown men feel diminutive in this way arose as a function of historic issues around race, gender, and hierarchy, where the garden is traditionally the domain of the woman of the house and having a ‘boy’ working for a woman, in her space and taking her orders, was somehow more socially acceptable than having a man working for her.

Origins aside, the term persists today, suggesting that little has changed in relation to race and power in this particular arena in South Africa in the last 20 years. South Africa’s unemployment rate is measured conservatively at over 25 percent (Statistics South Africa, 2014). Gardening is an entry point to the job market for supposedly “unskilled” labor. A graphic example of the dire need for work and the role of ‘gardener’ as a catchall entry point is given by Kingdon and Knight in their 2001 paper on unemployment in South Africa, which reported a staggering 39,000 applications for 35 permanent jobs advertised for gardeners and cleaners at the University of Cape Town (Kingdon and Knight, 2001). Many gardeners do find themselves in more permanent positions, but must often juggle a number of gardening jobs on rotation through the week. In addition to local South African men, gardening has become a common occupation for migrant labor in South Africa.

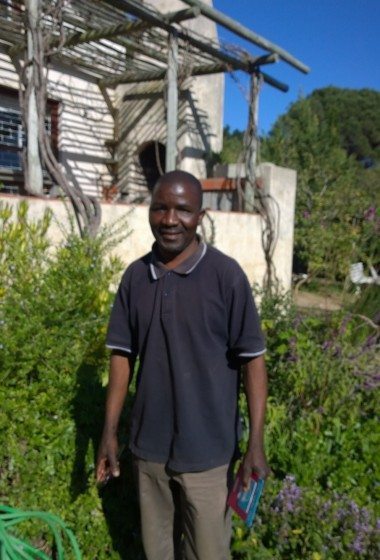

The men who tend these gardens make large contributions to the overall ecology and ‘nature’ of our cities. Interested in the dynamics between those directing their garden desires (garden owners) and the implementers of these desires (gardeners), I decided to speak to some gardeners in Cape Town. What brings them into this field of work? How do they view their roles as the ‘enactors’ of other people’s views of nature and greenery? For the purposes of this essay, I only spoke to a handful of gardeners, but this marks the start of a larger project and more interviews will be necessary to confirm the preliminary views noted below. Out of respect for concerns around privacy, in particular for those foreign nationals working in South Africa who expressed concerns about legitimacy and xenophobia, the names used here have been changed. However, interviewees were mostly happy to have their photographs taken and shared.

With the exception of one migrant gardener from Malawi who is a professional teacher, all the gardeners I spoke to consider themselves skilled workers with a deep understanding of plants, nature, seasonal cycles, and soil. Several of the gardeners I interviewed voluntarily shared photographs with me by mobile phone of the gardens in which they work: their desire to share pictures of their work is indicative of pride in that work. All the garden photographs shared in this blog are courtesy of Isaac Mgedezi and Samson Malunga. The universal willingness to be interviewed and the enthusiasm with which gardeners approached the interview gave me the impression that this was a group of people who had never been asked about their jobs in a professional manner and were delighted to have the opportunity to share their views and insights. I make particular reference to this as I am confident that this is not how these men are perceived by most people that employ them. The first ‘discomfort’ I will note emerges here, around perceptions of ability, understanding, and professionalism.

“We are farming people”

All the gardeners I interviewed had grown up in rural neighborhoods and gardened alongside parents or grandparents as children. All had fond memories of these childhood spaces or ‘first landscapes’ and were confident that these early experiences had informed their interests in nature and gardening. The Malawian gardeners all looked somewhat dumbfounded when I asked where they learnt their gardening skills, and while they noted that they grew up in family gardens, the much more emphatic response was generally: ‘I am Malawian, we are farming people’.

With the exception of one gardener who sometimes takes his son to work with him when he helps out in a community food garden close to his home, none of the gardeners was currently raising his children with the same degree of exposure to gardens and gardening that he had in his own childhood. While the gardeners have confidence and pride in their role in molding the gardens of our cities, the lowly pay and lack of professional recognition and security are all aspects they do not wish for their children. Their repeated references to very low wages, persistent poverty, the constant need to search for extra days of work here and there, and the relief expressed by those who have permanent jobs, all speaks to the very difficult emotional and economic space occupied by gardeners in South Africa.

Another apparent discomfort emerges around issues of power and autonomy. Gardeners expressed deep frustration at not having their views and understanding of the workings of plants and soil taken seriously. This is a consistent theme: gardeners feel the garden owners who, in their view, have less understanding about gardening, should be more willing to listen. Isaac said, ‘I get frustrated when my expertise is not respected … I really understand soil and what can grow in different soils’.

There are, of course, references made to particular garden owners who do consult their gardeners, who open opportunities for discussion, and—in one instance—who even allows the gardener to accompany them to the nursery and on the odd shopping trip. However, these cases were certainly the exception. One gardener expressed irritation at having to share his workspace with another gardener who comes on a different day. Andrew Makwena says, ‘I don’t like to work with others. I speak to the seeds and flowers I plant and don’t want someone else interfering with that’.

In addition to not liking the interference of others in the work of the garden, Andrew gave a fascinating insight into the frustrations of working in space owned by others. He talked of pruning roses and then watching buds emerge and going every day to see how a single bloom is coming along, only to arrive at work one day to find the flower ‘gone, cut off and taken away into the house’; his immense disappointment and irritation at this aspect of working in other’s gardens was apparent.

Dream garden

I asked each gardener what their own dream garden would look like. Most called for more order, less mock wilderness; all desired an element of productivity, with a food garden included. All wanted a lawn on which to ‘lie in the sun’ and ‘play with the kids’. On the whole, they wanted flowers, too, with a particular preference expressed for Agapanthus africanus flowers. Only the teacher, Devout Masuso, an economic refugee currently working as a gardener, expressed impatience over the planting of flowers, saying he would not waste his time with flowers but would plant his favorite Malawian fruit and vegetables such as ‘impiru’, a leafy green which he described as quite delicious. One gardener drew a blank in response to my question, responding, “I really don’t know. I can’t imagine. I think you need money to be able to dream like that.”

Most of the gardeners acknowledged sharing information on plants and gardening techniques with other gardeners they know. Several agree that they move plants around, in particular from the gardens they work in to those of their rural homes. Isaac says the last time he went back to the Eastern Cape to see family, he took several cuttings of flowering plants home with him. The gardeners’ homes in Cape Town are generally too small to allow for any gardening. Spaces are shared, overcrowded, and not owned by the gardeners themselves.

My interviews suggest that gardeners in South Africa occupy a shadowy space where they seldom fall under the direct gaze of anyone in their professional lives. They all relished the opportunity to speak of their work and expressed frustration at being under-recognized in their professional capacity. Discomforts are evident around recognition and autonomy. My interviews reveal a community of interested and engaged gardeners with a keen understanding of the plants, seasonal rhythms, and soil; they are hungry for professional recognition. These men operate in networks where they share ideas, information, and plants with each other. They are working in multiple gardens in our cities and green spaces in our broader landscapes. These are the people who tend the 20–30 percent green cover that our gardens represent in the ever-increasing footprint of the cities of the world. I think there needs to be greater social acknowledgement, greater engagement with these critical players in our urban ecological space. The informing role of gardeners certainly warrants further investigation.

Just as in real life, the representation of gardeners in literature is few and far between. Where reference to gardens abound, the gardeners are largely overlooked. A quick inventory gives us little more than the foolish, two-dimensional gardeners in Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, old Ben Weatherstaff in Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden, and Michael K in J. M. Coetzee’s The Life and Times of Michael K. [picture of the Alice in Wonderland Gardeners] Michael K demands the most attention, and ideas around gardening and being a gardener are threads that weave their way throughout the book. K gives us the best plea for the gardener, suggesting the gardener’s role as knowledge broker between the earth and those that live on it:

‘… enough men had gone off to war saying the time for gardening was when the war was over; whereas there must be men to stay behind to keep gardening alive, or at least the idea of gardening; because once that cord was broken, the earth would grow hard and forget her children, that was why.’

Pippin Anderson

Cape Town

References cited

- http://www.statssa.gov.za/presentation/Stats%20SA%20presentation%20on%20skills%20and%20unemployment_16%20September.pdf

- http://www.csae.ox.ac.uk/workingpapers/pdfs/2001-15text.pdf

“The gardeners in Alice in Wonderland are out painting the flowers. ‘Would you tell me,’ said Alice, a little timidly, ‘why you are painting those roses?’ Five and Seven said nothing, but looked at Two. Two began in a low voice, ‘Why the fact is, you see, Miss, this here ought to have been a red rose-tree, and we put a white one in by mistake; and if the Queen was to find it out, we should all have our heads cut off, you know.”

Hi Pippin

I agree a difficult life for these men earning minimum wage. However your comment about the gardeners wanting more order betrays, I think, the real story with regards their skills level. I’m 48 and have had many ‘gardeners’ since about 30 years of age. Only once or twice a week.

About 5%, if that, know anything at all about plants and so I know that your survey was either highly selective or biased. The ‘gardeners’ I’ve known slash and burn. They know huge trenches around grass edges. They know picking up every last leaf and weedy looking plant from the ground. Creating swathes of red sand, sometimes even sweeping the sand. Lopping off shrubs with hedging shears. Piling up sand around tree trunks. I could go on.

Quite honestly most white people in SA are also rather ignorant about horticulture so there is little teaching going on. People are more about landscaping than plant care and most remember their mother saying the sand should be constantly turned, not knowing horticulture has moved on from those old practices.

But your article suggests that these men have green fingers. When I’ve started teaching them, whether Malawian or not, I find they haven’t known or been taugh about soils, photosynthesis, or even when to water or plant names beyond the obvious. Certainly in South Africa, certainly the Zulu men learn from swept ‘farm’ gardens back home.

Besides old men, there are almost none who don’t want to leave to become a plumber or find another better paying job. There is no money in this line of work, so by definition there are no skills being developed. So gardeners who find a knowledgeable employer like me don’t stay long enough to learn much. Not blaming them either for that.

A true gardener is rare among the educated but among the uneducated even rarer. An instinctive love for plants and nature has somehow been stamped out of people and just cultivating that appreciation is an uphill battle.

So what is the purpose of this? Mainly just unloading my frustration. But maybe it’ll give you some feedback from a gardener.

And the answer for the homeowner? Be rich and willing to pay someone to stay or limit the scope of their work. For the men I suppose it can only be education against the odds. Townships and bantustans didn’t teach them a love for nature for its own sake. Littering is endemic here. The difficulty with teaching gardening is inspiring the initial but essential passion for nature. One finds black horticulturalists now, but compared with the black population it’s a tiny group. Even within the similarly historically deprived Indian population there is a relatively smaller group of people who want a garden as opposed to a paved courtyard with a potted lollipop tree.

i live in south wales u.k, and am approaching 50, and am currently unemployed, when asked by my children what woulid i like to do, i reply either baking or gardening, as i get into my middle years and see our world population grow i believe that agriculture and horticulture will be one of the world’s sought after employees on a national scale, so to those garden boys head up you have a wonderful skill set which will benefit you all your life.

I do my own planting, but call in a garden service to prune trees.

I garden for biodiversity and was Googling – gardening Cape Town. Not much which is blog or interesting reading to be found. But it did eventually bring me to your article.

Dear Melinda

Thank you for your comment – the slow response is partly due to the site being hacked…and my life being constantly hacked too (by children, students etc). I was so delighted to read the article link you posted. I really enjoyed it and felt the ‘call to arms’. I think the issue of discomfort is an interesting one and something we all need to embrace in the environmental revolution that the world so badly needs. It is most certainly needed in the South African context, and there are once again stirrings I believe towards necessary (and often uncomfortable) conversations.

Kind regards, Pippin

A really good article. Gardeners are very special people – so much knowledge hidden or taken for granted. Very interesting to read about South Africa and the slow steps towards equality.

Perhaps some readers might find this link interesting – it’s an extract from the South African judge Edwin Cameron

http://ohrh.law.ox.ac.uk/bram-fischer-dissent-and-challenge-from-within/

Melinda Janki, IUCN Urban specialist group