New York City is home to more than 600,000 street trees, according to some estimates. But good luck finding any one of those trees on a map—that is, until now. For the first time ever, the NYC Department of Parks and Recreation is working with thousands of volunteers to measure and map every single street tree on every single block in every single neighborhood in all five boroughs of the city.

Every. Single. Tree.

As if the sheer numbers weren’t enough of a challenge, the small army of volunteers—five thousand and growing—is using old fashioned site-surveying techniques to determine the location of all those curbside trees. No GPS. No Google Street View. No satellite imagery. Just a $90 measuring wheel, a plastic tape measure, and a meticulously designed data logging website filled to the brim with sophisticated geometry, cartography, and code. The whole improbable effort goes by the name of TreesCount! 2015 and it’s inviting New Yorkers to finally see the urban forest for all of its individual trees.

Why would one of the most technologically savvy cities on earth choose to map all of it street trees using methods familiar to, say, a seventeenth century Dutch farmer plotting out the boundaries of his land at the southern tip of Manhattan Island? Three simple answers: the method is cheap, it’s reliable, and it’s easy for volunteers to learn. Developed, tested, and refined by TreeKIT during the past five years, the mapping method asks volunteers to measure the distance between trees lined up along a street edge and an easy-to-estimate “start point” at the nearby intersection. You can learn more about the details behind the method here, here, and here (full disclosure: I co-founded and co-direct TreeKIT with my longtime collaborator Liz Barry, another participatory research enthusiast based in NYC). Volunteers have mapped nearly 100,000 trees since the initiative kicked off in late May and the speed with which new trees are added to the map seems to be accelerating week by week.

Mapping street trees is only partly the point of TreesCount! 2015. NYC Parks, the department that oversees street trees in the Big Apple, wants to know what kinds of challenges each tree is facing and how much effort neighborhood volunteers are putting into keeping trees alive. TreesCount! volunteers record the circumference of every tree, their perceptions of the tree’s health, evidence of problems that could interfere with the tree’s growth, and signs of volunteer stewardship—things like mulching, perennial flower plantings, tree guard installations, and more. All of that data will help shape public policy and municipal spending on large scale initiatives to do the yeoman work of urban forestry: digging up and grinding old tree stumps, widening tree beds, removing metal grates encumbering tree roots, and planting more and more trees wherever they can fit.

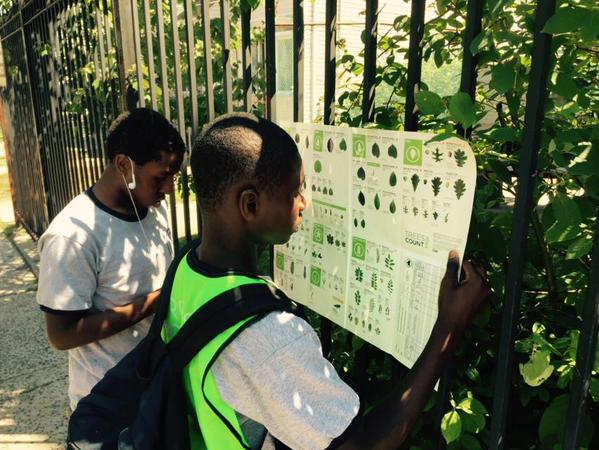

And who are these thousands of volunteers stepping up to stroll along the city’s busy sidewalks wearing garish green safety vests and pushing bright orange measuring wheels? It seems people of all ages and backgrounds have offered to help, with neighborhood-based organizations across the city mobilizing local residents with help from NYC Parks. Volunteers complete an online mapping tutorial before hitting the streets with NYC Parks staffers for in-person training. After about an hour of instruction, they fan off in groups of two or three to map a proscribed area of the city.

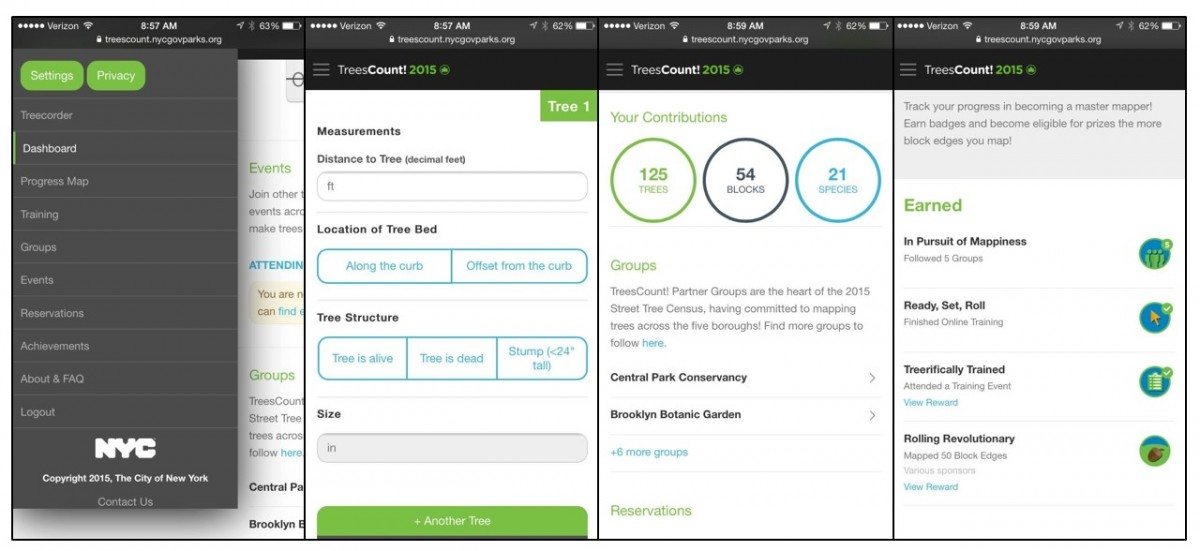

The whole thing hinges on an elaborate and elegant website developed for TreesCount! 2015 by the incredible team of geo-coders, designers, and developers at Azavea, the Philadelphia-based B-corporation behind the celebrated OpenTreeMap currently in use in cities around the globe. Volunteers can sign up on the website, complete their online training, track mapping progress in any given neighborhood, and check out blocks to map on their own time (after earning the right to do so by attending a training event and another group event hosted by a local organization or NYC Parks).

The website also contains the Treecorder, where volunteers log all of the data they collect in the field and submit it to NYC Parks for quality review. The Treecorder builds on previous efforts by TreeKIT to craft a mobile data entry platform for its mapping method, and the original nugget of code that translates distance measures into mapped points still lives at the heart of Azavea’s intuitive and user-friendly application. Volunteers can interact with the site on any tablet, mobile phone, laptop, or desktop computer, and all of the site code was given an open source license so other cities can adopt and adapt it for their own needs in the future. Anyone involved in building web-based platforms that support citizen science projects would do well to spend some time exploring Azavea’s handiwork. They’ve set a new standard for excellence in this specialized area of web engineering and design.

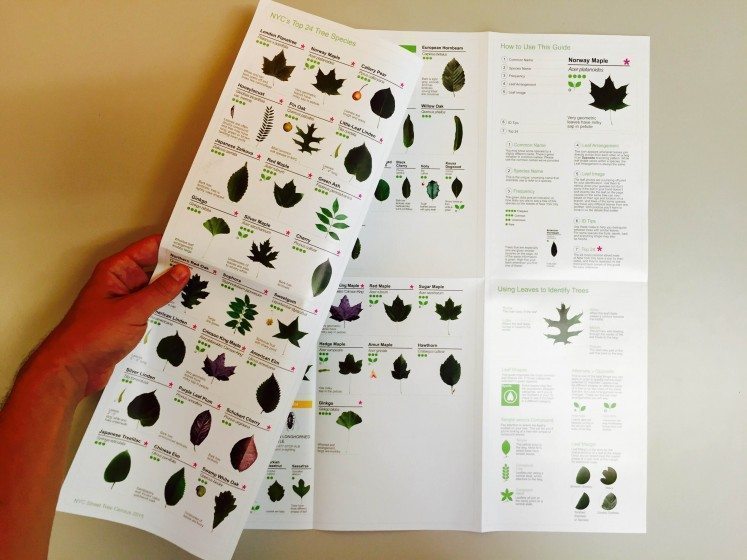

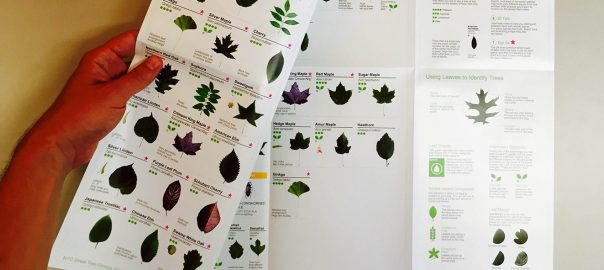

In addition to developing the mapping method that drives TreesCount! 2015, TreeKIT worked with NYC Parks to design and iteratively refine both the online and field training experiences for volunteers. Ray Cha, a user experience designer with extensive knowledge of online learning platforms, joined the TreeKIT team for this portion of the project. The online learning experience is interspersed with short self-assessments and ends with an “Explore Your Knowledge” quiz that gives volunteers immediate feedback on their understanding of the material. TreeKIT also designed an innovative street tree stewardship identification guide, pulling in horticulture and design expert Emily Vaughn to create the 16-panel foldout guide that NYC Parks is giving out to every volunteer. Dr. Alex Paya, an expert in tree science with a knack for Photoshop, contributed a collection of beautifully processed leaf images for the high-resolution guide, which is printed on tear-proof and waterproof paper for mapping in all kinds of weather.

More than sixty local schools, non-profit organizations, and government agencies signed up to serve as partner groups for TreesCount! 2015, hosting training sessions, leading special mapping events, and organizing volunteers to join the effort in every corner of the city. Partnering groups were given the chance to claim a batch of blocks to map on their own local turf, making this census much more of a grassroots initiative than previous tree counts held ten and twenty years ago. As of late July, the Washington Square Tree Counters—a group that formed in response to the census—has already mapped more than 90 percent of the blocks in their patch of Manhattan. They found just over 1,000 trees scattered across the neighborhood. AFROPUNK 2015, a massive music, art, and culture festival slated for late August, is giving out tickets to volunteers mapping trees across a wide swath of Brooklyn. Every one of New York City’s five boroughs is represented by a partnering group, and new groups can still sign up to participate until TreesCount! 2015 wraps up later in the fall.

NYC Parks plans to make the data harvested through TreesCount! 2015 openly available to the public, just like it did with the two previous tree counts (though both ’95 and ’05 were, strictly speaking, just tree counts rather than efforts to make accurate tree maps). A public-facing tree map, sponsored by the city, may someday serve as a convening ground and coordinating tool for the thousands upon thousands of NYC volunteers that help the city care for street trees. Until then, the TreesCount volunTreers (yes, just like the Treecorder, the pun was intended) have plenty of mapping to keep themselves busy.

Philip Silva

New York City

I really enjoyed your post about the TreeCount! initiative here in NYC. I think that technology can be a great way to make it easier for city governments and citizens to better understand how to make meaningful changes towards urban sustainability initiatives like tree planting and management.

I am currently a Masters student at Columbia University (also a Cornell grad!) and am taking a course in Urban Ecology. I wanted to reach out and see if you would be willing to conduct a short 5-10 minute interview about urban tech data solutions like TreeKIT, Azavea and Treecorder and how you think other NYC environmental initiatives could benefit from a similar data tools. Looking forward to hearing from you!

This is amazing. I have been recommending this kind of study for the city of Hyderabad in Telangana, a southern state in India. It has not got any takers in the government. I would love to get more details of the initiative and maybe I can try once more to convince the local civic body to take this up in Hyderabad.

I’ve seen those volunteers hard at work on my own Brooklyn block. Congratulations on a well-conceived and important program, a key step in raising awareness of the role our trees play in creating a greener, more resilient city. — Elana M., urban planner and urban studies adjunct professor.