According to the old urban paradigm, cities are crime-ridden, car-infested, unhealthy and over-crowded centers of humanity.

Could we conceivably cherish nature, respect others, grow our own food, earn a reasonable living, and enjoy a healthy and equitable urban environment?

Reversal of the old urban paradigm is not yet a given, especially when we take into account that people’s opinions are not usually based on facts, but on their perceptions of reality. I am sure that both contributors to this blog and its readers will agree that in an urbanized world, we should be heavily invested in marketing the new global brand: sustainable urbanism. However, I am not at all sure if this brand is perceived by the majority of city dwellers as worthy, desirable, or even identifiable. Thus, not only do the “country mice”, or rural dwellers, continue to feel superior to their brethren, the “town mice”, but the city dwellers themselves feel their quality of life is inferior in terms of its lack of nature.

I believe that most of us, by nature (not a pun), tend to pursue research or develop specific projects, and it is certainly good to know that many people around the world care about the quality of life in cities and see urban nature not only as a barometer of sustainability, but also as a factor contributing to biodiversity. I understand that urbanism is currently “in”, but for sustainable urbanism to thrive, we are going to have to work much harder.

The change in attitude to cities needs to take place at several levels. I will attempt to address the levels that are easy to identify, but there are probably additional layers to examine.

Individual and “social/cultural” mindsets: it is not easy to see past concepts that many of us grew up with. For example, if we want to breathe clean air, we should go “to the country”; we will find nature “in the country”; and we will grow our food, of course, on farms “in the country”. Even if we live in an enlightened city that has reduced emissions and pollution levels, improved its care for natural resources, and encouraged residents and communities to grow food locally, it does not mean that the residents themselves perceive their city environment as healthy.

Local government: there is a strange disconnect in the understanding of local government leaders: more and more people will be moving into cities, resulting in an ever-increasing need for housing, yet there is a lack of awareness of the need for cities to be really attractive and healthy places to live. It is therefore fascinating to see grass-roots, community-based initiatives building the fabric of solidarity and social frameworks that make neighborhoods livable and happy environments. This is an integral part of the new urban paradigm, in which bottom-up processes are setting the tone for community life. Local governments have grasped the need for urban densification, but will have to work together with their neighborhood communities to understand what is needed to make the renewed neighborhoods livable.

National government: in many countries, yet another disconnect results in the inability of local governments to revitalize their cities because national or regional legislation has impeded, or even contravened, local processes. This means that even when local governments manage to tune in to the needs of their neighborhood communities, their decisions are stymied by outdated national laws. An example from the local arena in Israel is the issue of garbage. The country set national targets to reduce the dumping of solid waste and to gradually increase the percentage of recycled solid waste, separated at source. This is admirable, but local governments were unable to provide incentives for their residents to separate waste at source, since the kind of tax reduction they wanted to offer needed to be approved at the national level. In the resulting impasse, national government continually complained that local governments were not meeting their recycling quotas, while the latter were complaining that they lacked the legislative power to offer their residents a financial incentive to recycle.

Global: It is not surprising that the mindsets that influence individual perceptions are the very ones that establish global trends. After all, experts in the U.N grew up like us: “knowing” that to breathe clean air, to enjoy the wonders of nature, or to grow food, we must head to a rural area.

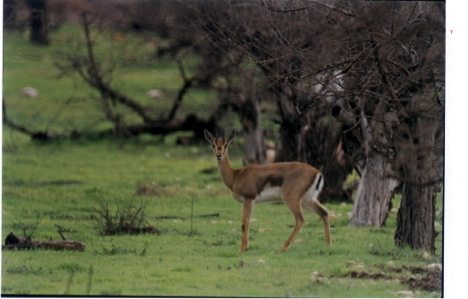

I am writing this contribution to The Nature of Cities in dismay—not in anger, yet with a touch of the innate optimism that has buoyed me through two decades of environmental campaigns, many of which have not only proved successful, but which have also been recognized as “right’’ and which have been vindicated by the establishment that initially rejected them out of hand. I have included pictures of two such examples from my own beloved city of Jerusalem. The “Gazelle Valley Park” and the “Railway Park” in Jerusalem resulted from a massive fights between civil society organizations and the planning authorities. Remarkably, today, those very same planning authorities cite these two parks as the key to sound urban development, each in its own setting.

These two examples illustrate another, equally important aspect of the reversal of paradigms in urban thinking. Local communities are turning out to be key players in the process of branding sustainable urbanism in a way that they never were before. Communities are rising to defend their urban nature, which is often integral to the cultural identity of their neighborhood.

In addressing the intricacies of the global transition from a rural to an urban world, I believe we should include the urgent need for a change in our perception of the role of nature in cities. Not only do residents fight to protect nature in their neighborhoods, realizing the important role of local flora and fauna, as well as the cultural values of our urban landscapes, but academics of global repute recognize that cities have an important role to play in protecting biodiversity. This role can be fulfilled much more effectively if we adopt the model of the inverted biosphere, whereby the large city at the center of a metropolitan hub recognizes its responsibility for the sensitive bioregion around it, along with the smaller towns and villages in the region. This model is being developed with considerable success by the Jerusalem Bioregion Center for Ecosystem Management by addressing cross-boundary issues together with the other stakeholders in the bioregion and by understanding the irrelevance, to this shared thinking, of statutory municipal or geopolitical boundaries.

The urban challenge facing the world is both simple and complex. Some will say this is the final and most tragic phase of a process that began with the industrial revolution. The continuing influx of individuals and families to cities in search of a livelihood, or, in some cases, the influx of desperate refugees fleeing persecution or a climate event disaster zone, is indeed producing a new generation of slum-dwellers alarming in its proportions.

This might imply that in cities that are neither in a disaster zone nor severely impacted by disaster, all is well. And yet, while it is true that there are many wonderful examples of sound urban practice, these are somehow the exception, while our job is to make them the rule. From the perspective of years of leadership in the environmental movement in Israel, and from a full term of office as Deputy Mayor of Jerusalem, I find myself taking a somewhat simplistic approach, and often wonder if that is perhaps the very thing we all need in our urban thinking, planning, and managing—simplicity. Just as when we set up an aquarium and want the fish in it to thrive, we put in appropriate plants to generate oxygen, and the kind of shells and stones that we believe will make them feel comfortable (although nobody really knows what a comfortable fish feels….). Why can’t we do the same in our cities? Why can’t we plan cities to be as beautiful and as healthy as possible for all the diverse communities living in them?

It is true that the approach to cities began to change when, in 2007, we were told that more than 50 percent of the world’s people were already city-dwellers. The current estimation is that by the end of the 21st century, 90 percent of us will be city-dwellers. This is an extraordinarily dramatic shift, compared with 15 percent of the world’s population living in cities at the beginning of the twentieth century. 2,500 years ago, when Aristotle penned his famous sentence, maintaining that “Man is a political animal”, meaning that human beings like to live in organized communities such as cities, he surely didn’t expect us to go so far….

One useful development came in the 1980s, when global city networks began to be established, and cities around the world began to talk to each other about their common challenges. Within their own countries, cities felt that their national governments were not always the partners they should be, and were strangely pleased to find that this was the case in other countries too. By the 1980s, the U.N was already talking about sustainable development but— being a community of nations, not cities—found it hard to relate to cities at all. The only U.N agency that actively concerned itself with cities was UN HABITAT, which is responsible for human shelter. The reason for its engagement with cities was simple—most human shelter occurs in an urban context.

In 2016, UN HABITAT will be hosting HABITAT III, focusing on the conditions of urban communities around the world. UN HABITAT has requested its member states to mitigate the disconnect between national and local governments by establishing national urban policy, to be debated and worked out by a national urban forum. In my simplistic world, this is a minor revolution in global thinking, since it recognizes a disturbing reality whereby national legislation often serves as an impediment to achieving urban sustainability, instead of assisting cities as they strive for a sustainable future.

This minor revolution is the latest in a short history of progressive actions. At the WUF (World Urban Forum) held in Naples, Italy, in 2012, Dr. Joan Clos, Director of UN HABITAT, requested member states to formulate urban policy at the national level. By the next WUF, held in Medellin, in April 2014, the process was already well under way and a special UN HABITAT team had been set up to visit countries and regions where nascent national urban forums were taking the first steps in “thinking urban” at a national level. In 2012 and 2014, delegations from my country, Israel, attended the WUFs. We appreciated the significance of Dr. Clos’ request and the possible benefit this could have for our country.

Israel is a tiny country which is already more than 90 percent urbanized, but has only just begun to think of the national implications of its intensive urban development. Profoundly influenced by the UN HABITAT vision, we have taken the first exciting steps towards the establishment of the Israel Urban Forum, which is to be launched in Akko in November 2015. There is a steering committee for this process, which has brought together representatives from government ministries, local government, academia, businesses, and NGOs. We are discovering just how many stakeholders there are in the urban arena and are inviting them all to contribute to an urban celebration in Akko, which will mark the creation of a multi-sectoral and multi-disciplinary platform for the better understanding of sustainable and equitable urbanism. We hope that the main product of our Akko conference will be the launch of the Israel Urban Forum in its capacity as a body of urban thinkers, that will continue to ponder the most intelligent solutions for the multiple challenges facing not only each city individually, but also the country as a whole, in the sense that it represents the collective of all the cities in Israel.

As Chair of the Steering Committee of the First Israel Urban Forum, I feel a burden of responsibility, as all of us who love our cities must surely feel at this time. In a 90 percent urban world, it seems that global sustainability will depend on urban sustainability, while the latter will depend on our joint ability to ensure that the cases of best practice in planning and management of our cities become mainstream—no longer the exception, but the rule. I would posit that on this front, failure is simply not an option.

Naomi Tsur

Jerusalem

Leave a Reply