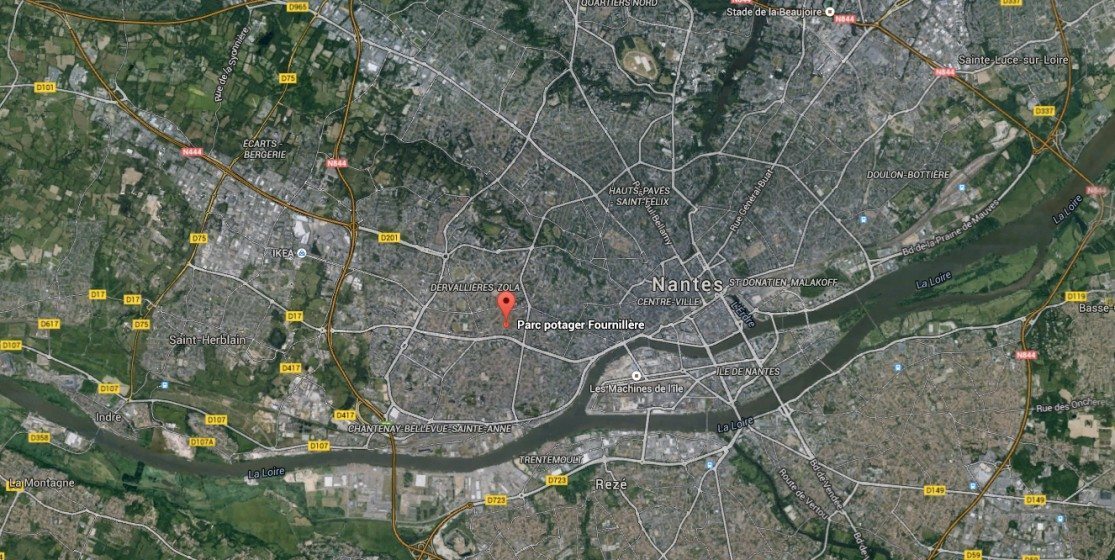

At the end of my last post, Unintended Consequences: When Environmental “Goods” Turn Bad, I raised the idea that sometimes environmental “bads” can also turn good, and that it usually works better when nobody “looks”. I mean that this process works better when the inhabitants take ownership of their living environment and transform it outside of any legal framework or official urban project, as the remarkable history of La Fournillère illustrates: there, inhabitants of the area turned a wasteland for squatters into a very popular park, combining leisure amenities and urban agriculture by the will of the people and with their own priorities. In the end, they manipulated the local authorities to enact their initiative—which was first reputed as “illegal”—into an official amenity.

Let’s start at the beginning and go back to the 19th century, when La Fournillère was just a village west of Nantes, in France. Indeed, La Fournillère was a small village, but it was on the verge of becoming an industrial suburb of fruit and vegetable canneries. Why did canneries decided to locate there? Well, the soil was rich, and the climate permitted cultivation of early vegetables with high added value, such as field peas, baby carrots, or asparagus. These canneries developed a policy of industrial paternalism and provided kitchen gardens to their workers. By 1908, La Fournillère was annexed to the city of Nantes; in the fifties, social housing complexes were built.

The kitchen gardens were still there, and the plot where they were established finally took the name of La Fournillère, while the former village vanished from the collective memory. Now, in 2015, as all the other kitchen gardens of the agglomeration of Nantes disappeared under the growing pressure from real estate development, La Fournillère is still alive and kicking: the plot now covers 3 hectares (7.5 acres) and has become a natural and cultural landmark for Nantes and its region.

What happened? First, a fortunate conjunction of circumstances, then, local people’s initiative and creativity, converged to preserve this improbable greenery in the middle of the city. Together with the social housing complexes came successive infrastructure projects that were supposed to be built, in the spirit of the post-war boom, on the site of the kitchen gardens of La Fournillère; the first one planned was an access highway to downtown Nantes. But as soon as they were designed, they were abandoned one after the other due to local political turmoil. The workers had been evicted from their kitchen gardens, but nothing happened after and the place turned into wasteland.

But the people living nearby—especially those from the social housing, who didn’t have access to nature—had their eyes on this abandoned land and its rich soils. After enough time had elapsed, they made their move! In the mid-seventies and later, one after the other, first at night, next in broad daylight, they progressively occupied La Fournillère. By the end of the nineties, there were more than 70 squatting gardeners at La Fournillère. To get a piece of land there “you simply have to start digging the ground somewhere—a corner that looks vacant—and wait. If nobody’s coming at you, you keep digging and tending your future garden. A few days more, or a week, without any hostility from your neighbors, means that this piece of land is ostensibly yours: you can start fencing, sowing, and socializing with your neighbors, as mentioned by Elisabeth Pasquier, who wrote a seminal book about La Fournillère. Today, two categories of squatting gardeners coexist at La Fournillère.

On the one side, some of the former evicted gardeners—or their children—came back. They are locals, who descended from Brittany or Vendée (French regions). They are few and they stick together in La Fournillère. They keep closely connected via common emblematic activities, such as pétanque (bocce tournament), aperitif (before-dinner drinks), or barbecues. This category of gardeners is made of poor but not marginalized people. They live in substandard one-family houses: usually old people with a small retirement pension or younger poor workers. They know how to cultivate a small piece of land.

On the other side is a completely different category. These gardeners come from the disadvantaged social housing complexes around La Fournillère. The new ones have different origins and ethnic backgrounds, being mainly Portuguese and North Africans. They are usually unemployed and live on social benefits. For them, “owning” a piece of land at La Fournillère is a way of getting of keeping active: in these new gardens they can develop a social network inside, but also outside, their own community. It is not all about vegetables and fruits, really. These gardeners are called “les autres” (the others) by the “local” gardeners that form the first category, but they represent an overwhelming majority, with nearly 4 gardeners out of 5. For them, La Fournillère is a place were they can settle symbolically—a “circulatory area” (territoire circulatoire), within the meaning of Alain Tarrius, and a place where they can grow roots literally.

Usually, both groups ignore each other. But there is, nonetheless, an element of solidarity that brings them together: they all are fully aware of how precarious and uncertain the future of La Fournillère is. They are squatters and they can be expelled at any time. These gardens don’t exist officially. Both groups know they have to be united to respond effectively to any of the many menaces that threaten their plot—a new urban project, theft and vandalism in their gardens from people from outside, etc. Such a situation fosters social links.

In the early 90s, the new city council of Nantes took interest again in La Fournillère, but this time with the project of creating a neighborhood park there. First, the gardeners were in shock. Most of them went claiming that if the city were going to stick its nose in their gardens, they’d rather leave the garden. But then, something happened. In a sudden about-face, both groups of gardeners—the original and the new gardeners, the “locals” and the “others”—started uniting their forces and organizing themselves collectively to impose their view on this project: they wanted their seat at the decision-making table and went for it. They also knew that the game of illegally occupying pieces of land couldn’t go on forever: it was time for them to make their situation legal, preferably in their own terms. A form of collective intelligence emerged, and with it the seeds of a collective identity.

Rather than making demands and organizing protests, they decided to draw out an in-depth report on the actual situation at La Fournillère, providing an exact overview with maps of the different pieces of land, including the spatial pattern of the different gardens and their history, all of which was realized with the help of Elisabeth Pasquier. The report displayed the long work of clearing and planting that they had done as well the public goods they had created, and illustrated the social and ecological value of these gardens for the whole city. They demonstrated that La Fournillère worked quite well as it was, whereas the project developed by the municipality could very well fail and destroy the whole site, unless it took into account their experiences and included the organization of La Fournillère as it currently stood. And finally, they claimed that they wanted to be decision-making partners in the project.

This time, the planners of the city of Nantes played smart. They understood that the opposition of the gardeners to the project was not just a negative NIMBY reaction, but the expression of collective knowledge and skills. Once they saw that what was happening—the emergence of an alternative proposal with strong local community (and, therefore, elector) support, they agreed to discuss with the gardener’s collective. According to both parties, the negotiations were no picnic, but at the end of a long process—and against all odds—the city council decided to support the gardeners’ alternative project and to abandon its own proposal. The alternative project envisioned a park organized around the existing kitchen gardens and organized under the form of islets or patches. Paths for walkers and runners entwined with these islets, connecting them. In the very center of the park would be a venue for initiating visitors to the recycling of material and waste in urban gardening, including waste sorting and composting to enhance biomass and biodiversity. The gardeners determined themselves what would be the rules for living together in the park: more frugal and wiser water-management; a ban on cutting any tree in one’s own gardens, since trees are considered to be common resources; etc.

What was the outcome of such a mysterious alchemy?

Let’s pay a visit to La Fournillère today. Placed in the middle of the city, La Fournillère is a particularly charming and unusually large urban greenspace. In essence, it is a weird farming plot that you can only reach by walking: to get there, one must take two narrow lanes that lead to a kind of huge clearing covered by gardens, scattered trees, and bushes. There, large, colored water tanks surround shacks made out of recycled materials, isolated or gathered in small patches. Plastic strips flapping in the wind form a strange parody of fencing. A maze of service alleys spreads around five key items: three wells, a pond, and an improvised pétanque court. Two larger paths cross the whole area. They were created by the footsteps of thousands of people: traversing La Fournillère is a shortcut for many men and women going to school, to work, or simply to the market in Nantes. And such a lovely shortcut it is, with flowers, trees, birds everywhere, wonderful scents, and friendly people. As a bonus, it gives the thrill of crossing a no man’s land without any official regulation, outside the world of master plans—a brief taste of freedom in an otherwise ordered life.

La Fournillère is also a social theater, where the gardeners perpetually reinvent values and attitudes to live together, as well as learn new agricultural skills. These kitchen gardens—predominately maintained by men, though a bit less recently—give these grown-ups a place where they can get away from it all and become kids again, a gang of Tom Sawyers playing in the wild, a modest parenthesis in their ordinary lives, since at the end of the day they’ll go back home. At La Fournillère, they mimic their household environment to better subvert it: a painting is clamped to the wall of a shack, but outdoors; a former doormat is turned into a blackout curtain, while an old curtain becomes a doormat. They indulge themselves by putting things in the garden that wouldn’t be permitted anywhere else in the city: a doll’s head impaled on a pole, a teddy bear crucified on a picket fence, pinup posters stuck to the walls of the shacks with the mention “beware of the bitch” (“Attention pute méchante”), etc.

Gateway Park (Huntington Station) – source villagetattler.com

Naturally, when you ask them why they do these things, the gardeners always have a rational explanation: the doll was found in a garbage can and is used to protect the tip of the stake; the teddy bear is used as a scarecrow; and so on. Sometimes the explanation is: “It is just fun”, as with the pinup posters. But hidden behind these simple explanations, developed so matter-of-factly, are some really weird and meaningful features: why are all these figures—the doll’s head, the teddy bear, the pinup—always positioned so as to look outwards, right in the eyes of the visitors? Why doesn’t the gardener cover all his stakes, if it is a matter of protection—especially considering that the tip of the unique covered pole protrudes from the doll’s head? Why is there such a proliferation of human and animal figures among the installations exhibited in the gardens (I previously spared you the description of a huge inflatable Casimir, an anthropomorphic orange dinosaur, which was the main character of a French kids’ TV show in the beginning of the 80s) or of big toy soldiers? Are these anthropomorphic setups there to protect the gardens when the gardeners are not there? Curiously enough, it appears that painted anthropomorphic figures are frequent at the entrance of the community gardens like in New York, for example at Gateway Park in Huntington Station. Are they some kind of kamkokolas? (The inhabitants of the Trobriand islands in Papua New Guinea fitted kamkokolas—vertical poles on which two smaller diagonal poles rest, where spirits are supposed to live and watch over the gardens— at every corner of their gardens). All these figures can be seen as attempts by the gardeners to take ownership of the gardens and protect them.

Apart from the magic of the place and its beauty, the gardens of La Fournillère also are kitchen gardens and have, as such, straightforward economic interests: cabbages, potatoes, and other vegetables are planted to feed the family year-round. Protecting this interest is a good reason to erect the gate-keepers discussed above, even though they are mostly symbolic.

One of the many merits of La Fournillère is surely that, in marginal lands, very different people found a way to build something really beautiful, to live together there and, finally, to stand up together to bring their views to the planners of the city in a very constructive way. As such, it is a symbol of what can be done when everybody gets involved in the planning procedures. La Fournillère is about the right to decide and the power to create, renewing and deepening what Henri Lefebvre calls Le Droit à la Ville (Lefebvre 1968).

The example of La Fournillère also gives us insight into how interstitial abandoned urban areas may be one of cities’ main seedbeds of creative innovation. To return to my opening point, it is about how environmental “bads” can be turned into environmental goods: in this case, an environmental that gives consistency to the whole urban fabric of Nantes emerged from what otherwise might have been a space of environmental bad. Though it may have been unwittingly, the gardeners’ actions contributed to the preservation of Nantes’s urban identity.

As I discussed in a recent paper (Mancebo 2015) a city does not arise from the sole will and skill of architects, planners, surveyors, and politicians. Like a golem, a city has to be nurtured and molded by its inhabitants, which finally put their values in its mouth to bring it to life. And such a process needs time. Quite differently from the frenetic timeline and knee-jerk reactions to any opposition that elected officials and planners, guided by their own short-term interests (the next election, compliance with construction deadlines etc.), impose on urban policies, La Fournillère is a wonderful example of the proper use of slowness (Le bon usage de la lenteur) in urban planning, as depicted by Pierre Sansot (Sansot 2000). Grasping what happened at La Fournillère eventually means deciphering the eternal game between what the authorities, whatever their form, try to impose on the social fabric, and what the social fabric—here, the gardeners—impose on the authorities, through deception or force, through confrontation or bargaining. It is all about how people take ownership over their own city.

François Mancebo

Paris

Works Cited

1. Lefebvre H., 1968, Le droit à la ville, Editions Anthropos, Paris.

2. Mancebo F., 2015, “Insights for a Better Future in an Unfair World – Combining Social Justice with Sustainability”, in Transitions to Sustainability, Mancebo F., Sachs I. eds, pp. 105-116, Springer.

3. Sansot P., 2000, Du bon usage de la lenteur, Rivages Poche.

Add a Comment

Join our conversation