“We all know the sound of two hands clapping. But what is the sound of one hand clapping?” says a famous Zen Koan. At first consideration, it seems impossible to conjecture about the “just city” without having already in mind what is an “unjust city,” and vice versa. But my opinion is that this is wrong: It is possible to define what a “just city” is per se. To give flesh and substance to this essay I will focus on Paris and sustainability. First, because they are my fields of expertise, but also because sustainability and justice are two alleged priorities cited lavishly by the planners and elected officials to promote their urban policies. Their doxa considers that these two priorities are perfectly synergistic, but they are not. Planning for one may produce redlines in the other: sustainable policies often increase social injustice, as shown by Elizabeth Burton in a large sample of UK cities, or by Neil Smith when he denounces the veil thrown over profoundly unfair environmental dynamics that involve the departure of socially vulnerable people out of newly gentrified ecological neighborhoods. In fact sustainability and justice are like two rival brothers, and combining them in urban policies is certainly challenging.

“We all know the sound of two hands clapping. But what is the sound of one hand clapping?” says a famous Zen Koan. At first consideration, it seems impossible to conjecture about the “just city” without having already in mind what is an “unjust city,” and vice versa. But my opinion is that this is wrong: It is possible to define what a “just city” is per se. To give flesh and substance to this essay I will focus on Paris and sustainability. First, because they are my fields of expertise, but also because sustainability and justice are two alleged priorities cited lavishly by the planners and elected officials to promote their urban policies. Their doxa considers that these two priorities are perfectly synergistic, but they are not. Planning for one may produce redlines in the other: sustainable policies often increase social injustice, as shown by Elizabeth Burton in a large sample of UK cities, or by Neil Smith when he denounces the veil thrown over profoundly unfair environmental dynamics that involve the departure of socially vulnerable people out of newly gentrified ecological neighborhoods. In fact sustainability and justice are like two rival brothers, and combining them in urban policies is certainly challenging.

Thus, a sustainable city should result from the confrontation—or the synergy—of choices made by multiple actors, each acting for its own concern. But usually, only elected officials, developers and technical staff are invited at the table, which is a big mistake. All those who are affected by the decisions should be involved in the process of decision-making, as shown by the failure of the Trames Vertes et Bleues (Green and Blue Grid) in the region of Paris (a land management tool for the preservation of biodiversity). Local and regional authorities forgot a few things when fixing them. They forgot that livability, justice and sustainability are technically three different things, but three things that should contribute together to what the people affected by their policies will call a “good environment.” A “good environment” is one in which the improvement of environmental conditions stricto sensu (water quality, air, biodiversity, etc.) leads to improved living conditions. A polluted environment can be a place where life is good. Conversely, an environment with clean air and clean water can be quite intolerable as evidenced by windswept segregated social-housing complexes settled in the middle of nowhere, where the quality of life is low. The developers of Trames Vertes et Bleues just didn’t care to ask the people what a “good environment” was for them, even less did they make room for them at the decision-making table, as I explained in a recent paper. Do you know that the current regional master plan of Paris proposes—as an important mean to foster sustainability—a quantitative objective of 10m2 of public green area per inhabitant? As though it were sufficient to display “green” to become suddenly sustainable. Amazing, isn’t it?

In fact, urban sustainability should be about designing a new social contract that addresses the following questions: What type of society do we want to live in? Which compromises are necessary between the goals and interests of the different actors?

Well, the very notion of a social contract has a lot to do with justice—at least social justice—right? Which raises a tricky issue: What can we say about “Justice and the City?” (No, it is not a new sitcom, it is a real question.)

Let me dig into my own history to answer this question as clearly as possible. I was born in Paris. I grew up in a neighborhood called La Goutte d’Or, east of Montmartre, bordered by railways, technical facilities, and railroad tracks. Not a nice place to live. In the 19th century, Émile Zola set there the plot of his novel L’Assommoir, depicting it as a miserable slum. In the sixties, it was a highly disadvantaged place, characterized by substandard housing and violence in the streets. It still is.

I remember that in the seventies the Paris City Council initiated a program of urban renewal: libraries, parks and gardens (square Léon and square Amiraux-Boinod) were created, as well as swimming pools (piscine des Amiraux, piscine Bertrand Dauvin). Did it change anything? Not even the slightest. The content of the trashcans still littered the streets. Substandard housing was still there. So were the drug dealers and thugs. What happened, or better, what did not happen that should have? Well, nobody frequented these new libraries, parks and pools. The population stuck to its usual way of living, as if these amenities were not for them. They were perceived as vague threats, put there only by the will of planners and local moguls, rather than opportunities for a richer life. It was not so much a matter of access and capability really. The people decided not to use them, because they considered that they didn’t belong to their world. They built an invisible wall between themselves and these amenities.

Nowadays, La Goutte d’Or has become a “Sensitive Urban Zone” (ZUS), a prioritized urban area characterized by high percentage of public housing, high unemployment, low percentage of high-school graduates, and huge security issues. For the record, it was the ZUS that were misrepresented by Fox News in January 2015 as “no-go zones”.

As a teen, each and everyday day I crossed another invisible wall to go to a Parisian high school in Montmartre, which was already a fashionable place to live. Lucky me! My father was a refugee from Spain, and I benefited from a better cultural background than most of the kids in my age group. I skipped a grade and had the chance to integrate into a high school outside La Goutte d’Or. Out of more than 200 kids in my neighborhood, only three of us had this option. When I wonder what my other schoolmates became, I feel a bit depressed. Anyway, three of us were going to school out of La Goutte d’Or, and I remember our discussions: Why do we never meet our old friends there? Why do they never cross the line? We did, everyday, and nobody ever treated us badly. There were no official boundaries, no gates confining them in a ghetto. They could go to the cafés, to the movies or just walk the nice streets and hang out there. But they didn’t. They didn’t feel like they belonged to this other Paris.

What does my experience say about justice and the city in Paris? It says that people suffering from bad living conditions, are not only victims of planning procedures, hidden political agendas, segregation or whatever else—or at least they are not only victims in need for help. They also are actors whose choices, convictions and presuppositions contribute to maintain, to worsen, and even in some cases to create the miserable condition in which they live. In the case of La Goutte d’Or internal social barriers got transformed into internal spatial barriers—invisible walls.

These invisible walls go both ways. Let’s turn our attention to the case of Seine-St-Denis, north of Paris. The place has a very negative image, both for its inhabitants as well as for the Parisians living outside. It is associated with environmental shortcomings due to its industrial heritage. The prejudice remains very strong despite deindustrialization forty years ago and despite many major urban regeneration programs, among them sustainable neighborhoods and green areas. To this day it is a “bad area” and a stigmatizing place to live in. It is not a coincidence that almost all of last year’s French urban riots took place in the large housing complexes of Seine-Saint-Denis. As mentioned by Susan Fainstein, desirable end states and the forces to achieve them should be contemplated simultaneously in urban planning.

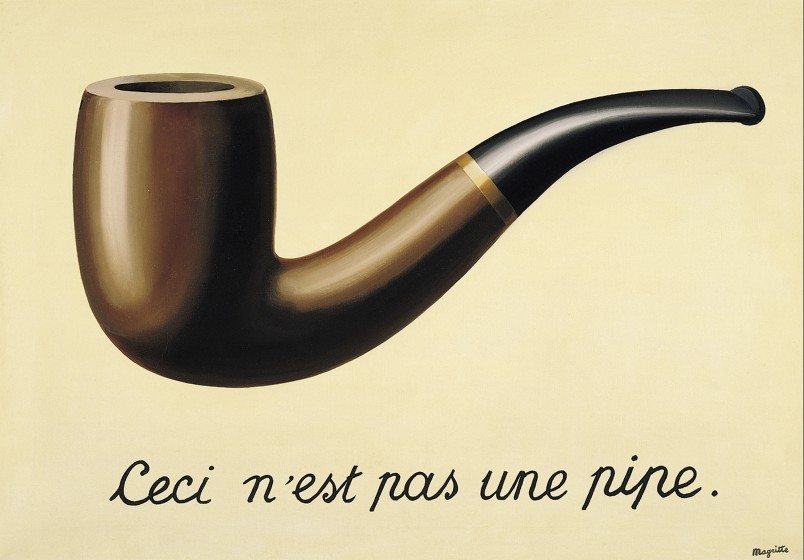

This means that fostering a just city is not about repairing previous mistakes to help people reduced to the status of “victims.” It is not about undoing what seems unjust. It never works. The expressions of injustice are exactly what they look like: expressions, representations, and symptoms that something has been going wrong. They are like the pipe in the famous painting of Magritte, called “The Treachery of Images.” It shows a pipe, and written under it are the words “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (This is not a pipe). This statement means that the painting itself is not a real pipe. You can’t smoke it. You can’t touch it. Similarly, the expressions of injustice are the result of complex dynamics. We cannot make things better only by opposing the expressions of injustice in the city. It would be like treating a disease only by addressing only the symptoms, or trying to smoke the pipe of Magritte.

This means that fostering a just city is not about repairing previous mistakes to help people reduced to the status of “victims.” It is not about undoing what seems unjust. It never works. The expressions of injustice are exactly what they look like: expressions, representations, and symptoms that something has been going wrong. They are like the pipe in the famous painting of Magritte, called “The Treachery of Images.” It shows a pipe, and written under it are the words “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (This is not a pipe). This statement means that the painting itself is not a real pipe. You can’t smoke it. You can’t touch it. Similarly, the expressions of injustice are the result of complex dynamics. We cannot make things better only by opposing the expressions of injustice in the city. It would be like treating a disease only by addressing only the symptoms, or trying to smoke the pipe of Magritte.

Oh, wait a minute . . . but we tried for decades and are still trying, with nothing to show for it but gutted neighborhoods.

Two or three years ago, I paid a visit to La Goutte d’Or. Nothing had changed. Well, actually it is not all that true. The environmental goods that rained down La Goutte d’Or—parks, plazas, cleanups, etc.—produced some results, though very slowly, and not the ones that were expected. In the last two or three years the structure of the population has begun to change in some patches, such as place de l’Assommoir, villa Poissonnière or rue Polonceau. An embryonic gentrification is underway there, with a continuous and lasting rise in house and apartment prices (+ 144 % in only 4 years). Where are the evicted people relocating? Who knows? If this is going to be the only result of these “repairing” policies, it really is a miserable one.

The more top-down repairing planning procedures, the fewer results. Building a just city is something different, completely. It requires involving everybody in the decisions and the definition of the policies, not only of their neighborhood but also of the city as a whole, as I showed in a recent article where I developed how local actors, non-market organizations, local communities and individuals able to form self-determined user associations should be involved in the making of the city. The just city requires the right to decide and the power to create, renewing and deepening what Henri Lefebvre calls Le Droit à la Ville (The Right to the City).

It’s sitting everyone at the table, so that all the inhabitants understand that the urban affairs are also their affairs. It is about erasing the invisible walls. In a very recent post for The Nature of Cities. I showed how the inhabitants of La Fournillière—a neighborhood of the French city of Nantes—erased one of these walls by turning a wasteland into a very popular park, combining leisure amenities and urban agriculture. They did it outside any legal framework, but they knew how to play the eternal game of deception and force, confrontation or bargaining with the local authorities, so that at the end of it their reputed “illegal” initiative turned into an official amenity.

I don’t pretend that sitting everyone at the table will suddenly make poverty, segregation, or lack of access disappear. It will not. But such an approach—even if insufficient—is the necessary condition to design and carry out a just city.

François Mancebo

Paris

The Just City Essays is a joint project of The J. Max Bond Center, Next City and The Nature of Cities. © 2015 All rights are reserved.

Thank you for your comments Alexandria,

You can find some answer (at least mine) to your interrogation, in another posts at TNOC (“The Nurtured Golem: A Nantes Neighborhood Transforms Environmental Bad into Good”). I think that we (policy makers, activists, social workers, planners, politicians etc.) cannot “give” the citizens anything, and certainly not restore confidence through willful actions. Is our purpose making “everyone to act within the same framework”, or creating the conditions in which they can discover by themselves how they can act (with as many different ways as there are different people)? In this perspective (and in my opinion), we should act like midwives, i.e. leaving “blank areas” where people can develop their own vision of the city, build their own world, and take ownership of their environment. Only then, is it possible to accompany their actions and give their creation a legal framework within the city: This way, they get a seat at the decision-making table of the affairs of their city, which results eventually in breaking the “invisible walls”: Once you feel you are considered and recognized for what you do, and once realize that you can you’re your own decisions…. you become an actor and it changes everything.

Thank you for your essay, I appreciate the Magritte touch.

I especially appreciated your conversation on ‘invisible walls’ and all citizens as actors. I read about an initiative done in Bogota in the 90s by Mayor Mockus (I actually read about this in another just cities essay), which reminded me of your essay. Mayor Mockus used top-down approaches to reengage the citizens who were accustomed to things like corrupt policemen and an inefficient government.

In your essay you discuss the importance of a bottom-up approach and engaging everyone in the building and decision making of the city. I completely agree with this sentiment, but I also wanted to add that sometimes the citizens have become so detached that they need to be reengaged. Need their faith restored in the government, and the processes.

I was wondering if you had any thoughts on this. On how to engage citizens in the conversations, how to give them access and give them a voice, as you say everyone in the city is an actor, how can we get everyone to act within the same framework?

Thank you.