Resilience is the word of the decade, as sustainability was in previous decades. No doubt, our view of the kind and quality of cities we as societies want to build will continue to evolve and inspire new descriptive goals. Surely we have not lost our desire for sustainable cities, with ecological footprints we can afford, even though our focus has been on resilience, after what seems like a relentless drum beat of natural disasters around the world. The search for terms begs the question: what are the cities we want to create in the future? What is their nature? What are the cities in which we want to live? Certainly these cities are sustainable, since we want our cities to balance consumption and resources so that they can last into the future. Certainly they are resilient, so our cities are still in existence after the next 100-year storm, now due every few years. And yet…as we build this vision we know that cities must also be livable. Indeed, we must view livability as a third indispensible leg supporting the cities of our dreams: resilient + sustainable + livable.

Resilience is the word of the decade, as sustainability was in previous decades. No doubt, our view of the kind and quality of cities we as societies want to build will continue to evolve and inspire new descriptive goals. Surely we have not lost our desire for sustainable cities, with ecological footprints we can afford, even though our focus has been on resilience, after what seems like a relentless drum beat of natural disasters around the world. The search for terms begs the question: what are the cities we want to create in the future? What is their nature? What are the cities in which we want to live? Certainly these cities are sustainable, since we want our cities to balance consumption and resources so that they can last into the future. Certainly they are resilient, so our cities are still in existence after the next 100-year storm, now due every few years. And yet…as we build this vision we know that cities must also be livable. Indeed, we must view livability as a third indispensible leg supporting the cities of our dreams: resilient + sustainable + livable.

So this imagining needs a fourth leg. These are the cities of our dreams: resilient, sustainable, livable, just.

Let’s imagine.

We can imagine sustainable cities—ones that can persist in energy, food and ecological balance—that are nevertheless brittle, socially or infrastructurally, to shocks and major perturbations. That is, they are not resilient. Such cities are not truly sustainable, of course—because they will be crushed by major perturbations they’re not in it for the long term—but their lack of sustainability is for reasons beyond the usually definitions of energy and food systems. We can imagine resilient cities—especially cities that are made so through extraordinary and expensive works of grey infrastructure—that are not sustainable from the point of view of energy consumption, food security, economy, or other resources.

We can imagine livable cities that are neither resilient nor sustainable.

And, it is easy to imagine resilient and sustainable cities that are not livable — and so are not truly sustainable.

Easiest of all is to imagine cities of injustice, because they exist all around us. The nature of their injustice may be difficult to solve or even comprehend within our systems of economy and government, but it’s easy to see.

The point is that we must conceive and build our urban areas based on a vision of the future that creates cities that are resilient + sustainable + livable + just. No one of these is sufficient for our dream cities of the future. Yet we often pursue these four elements on independent tracks, with separate government agencies pursuing one or another and NGOs and community organizations devoted to a single track. Of course, many cities around the world don’t really have the resources to make progress in any of the four.

Metaphor

A key problem for us, in all of these concepts, is that they exist so beautifully in the realm of metaphor. They work in metaphor. Everyone can agree that “resilience” is a good thing. Who wouldn’t want that? Raise your hand.

I thought so.

But an operational definition is really about difficult choices. Bringing a word like resilience—or sustainability, or livability, or justice—down from the realm of metaphor is hard because it quickly becomes clear that it is about nothing else but difficult choices. Choices that often produce winners and losers. We have to be specific about the choices involved in resilience or sustainability or livability or justice, and the trade-offs they imply. As societies we have to be explicit about these trade-offs—about their consequences. I think often we don’t have open and fair conversations about these issues because we don’t want to know about these trade offs, maybe not so much because we care about the losers, but because the winners of the world have so much to lose. Think developers who consume green space—often with the government’s blessing—without concern for sustainability issues or accommodations for the less wealthy. Or the growth- and consumption-obsessed nations driving the climate change that may destroy communities around the world, communities that have little responsibility that climate change.

Green

Most people in my circles make strong claims about the critical value of nature and ecosystems. Nature is thought to provide key benefits for resilience, such as technical aid to storm water management. Nature—and we way we use it—is the key foundation to sustainability. Nature cleans the air and water. It provides food. Nature provides beauty and serenity for people. This is all to say that nature and “green” provide immense and diverse benefits to societies, cities, and their people.

Do we believe these benefits are real? Are true? I do. If we believe in these benefits, then who should have access to them? Everyone. Does everyone have access to these benefits? No. That’s as true in Cape Town as it is in Los Angeles or Manchester.

If the benefits of green are true—in the broad sense of nature and in our approach to the built environment—then it is clear that issues of green and nature are also questions of justice, and that there is a key and essential role for nature to play in the notion of just cities.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has long had a definition of environmental justice. It intends to specifically address the fact that environmental “bads”—dumps, incinerators, legacies of industrial pollution, and so on—are disproportionally placed in poorer neighborhoods. That’s a fact that results from a host of reasons: inadvertent, economic, political and sometimes more cynical. Here is the EPA’s definition. Environmental justice will achieved:

…when everyone enjoys the same degree of protection from environmental and health hazards and equal access to the decision-making process to have a healthy environment in which to live, learn and work.

Many have written about the limits of this definition, although to me it is pretty strong and progressive, especially the part about decision-making. But it lacks the idea that everyone also deserves equal and fair access to environmental “goods” and the services they provide: healthy food, resilience to storms, clean air and water, parks, beauty. So an improvement to the definition, a more complete manifesto of belief, would be that environmental justice is achieved:

…when everyone enjoys the same degree of strong protection from environmental and health hazards, the same high level access to all the various services and benefits that nature can provide, and equal access to the decision-making processes for both to have a healthy environment in which to live, learn, work, and prosper.

Although some of the world’s cities are better than others in fulfilling this dream, probably none fully achieve it, although more embrace the idea of it. Most don’t even come close.

For example, there is a crisis of open space in many of the world’s cities. My city, New York, offers about 4m2 of open space per capita in the form of parks and plazas. Although the distribution of this open space is not entirely equitable (and some of the parks in poorer neighborhoods are of less quality) New York is to be commended for an explicit PlaNYC (New York’s long term sustainability plan) goal that says every New Yorker should live within a ten-minute walk of a park. We’re about 85 percent of the way to achieving this goal. This is the kind of specificity that can take green’s contribution to livability down from the level of metaphor and into on-the-ground evaluation and action.

Many of the world’s cities don’t fare so well. Although New York is a fairly dense city, Mumbai has 1 percent of the open space per person that New York has, its public commons gobbled up by cozy and opaque relationships between government and developers.

Not that the United States has so much to brag about. The Washington Post reported that in Washington DC there is a strong correlation between tree canopy and average income—the richer people get the benefit of trees. In Los Angeles, areas dominated by Latinos or African Americans have dramatically lower access to parks (as measured by park acres per 1,000 children) than areas dominated by whites. Countywide only 36 percent of Los Angelenos have close access to a park.

These are patterns the world over: when there are open spaces and ecosystem services at all, they tend to be for the benefit of richer or more connected people. This has to change in any city we would call just.

Values

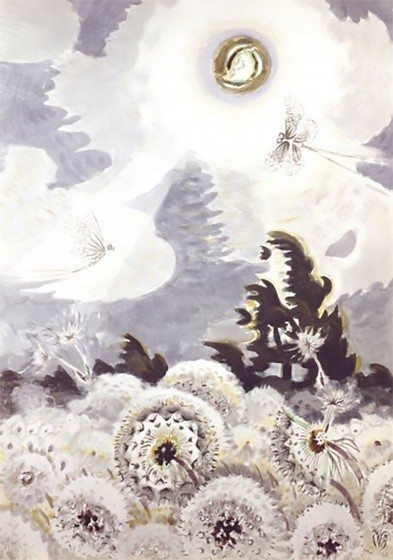

“It is difficult to take in all the glory of the Dandelion, as it is to take in a mountain, or a thunderstorm.”

Charles Burchfield (1893–1967) is legendary for his watercolor landscapes, painted near his Buffalo, NY, home. He was also a great journalist and over his lifetime wrote over 10,000 pages in various handmade volumes. It was there, on 5 May 1963, that he wrote the quote above.

And so they are difficult to take in, both for their beauty and their complexity. How can you describe and assess them? Convey them to one who hasn’t seen? You finally stumble, awestruck, into saying that they are “beautiful,” or “majestic,” or just “amazing.” But all of us—as scientists, decision-makers, participating citizens—typically have to comprehend, describe and quantify such entities and then communicate the results in ways that aren’t hopelessly obscure—that are somehow specific and not just metaphorical. That is, we need to communicate a very complicated thing in a simple, essential and, above all, useful way.

And so they are difficult to take in, both for their beauty and their complexity. How can you describe and assess them? Convey them to one who hasn’t seen? You finally stumble, awestruck, into saying that they are “beautiful,” or “majestic,” or just “amazing.” But all of us—as scientists, decision-makers, participating citizens—typically have to comprehend, describe and quantify such entities and then communicate the results in ways that aren’t hopelessly obscure—that are somehow specific and not just metaphorical. That is, we need to communicate a very complicated thing in a simple, essential and, above all, useful way.

We need to communicate what we value and build our cities accordingly.

Words like improvisation and imagination and intuition can sound awkward in the context of city-building and policy. Yet these are the very abilities that we require to be able to see past and beyond the details—this object is here, that process is there—to create and understand how a vast and majestic thing works and how it might change.

Perspective is another important word—a sense of what you value in the vision you are creating. The Dandelion seeds are close up in Burchfield’s picture. He values them. The sky is there too. You need to see the patterns and perspective and not only the details—the beating of the heart and not just the heart’s location in the chest.

How do you “take in” a complicated multidimensional thing like a mountain? Or a park? Or a community garden? Or a city? Or justice? It starts with an act of imagination.

It is this act that requires of us that we imagine, in specific terms, what the just city would look like. I think it would look something like the modified EPA definition I presented above. We already know what this just city doesn’t look like. You probably just have to drive around your own city. (My apologies if your city has solved this. Shout your solution from all the rooftops and soapboxes. The world needs to know.)

We need the imagination to dream about what this just city looks like, the nature of it, if you will. And then we need the courage to make it happen on the ground, by creating actual urban plans that address justice explicitly, that put justice into literal practice, in law and regulation and real action, the imagining of, say, the EPA definition, in detail, in all cities around the world.

To say this requires a sense of hope. Given the distance we have to travel to achieve just cities, in greenness or most any other sense, we have to hope.

A closing idea from Buzz Holling

One key [to resilience] is maybe best captured by the word “hope.”

Although Buzz Holling was an original elucidator of the ecological resilience concept, here he used a word that is fundamentally a human concept. What does it mean to hope? At its most basic, it is a desire for and the belief in the possibility of a certain good outcome.

So, here’s my vision of the just city. It’s green. It’s full of nature’s benefits, accessible to all. It is resilient, and sustainable, and livable, and just. It is a city that has a clear and grounded vision of what these words mean. It acts on justice and the place of nature in the city. It has the hope to believe that these things can can be achieved, and the courage and faith to bring them to life.

David Maddox

New York

The Just City Essays is a joint project of The J. Max Bond Center, Next City and The Nature of Cities. © 2015 All rights are reserved.

Very inspiring David

Integrating nature into our urban planning, design holds the promise to make cities more resilient, more livable happier and finally prosperous places.

Thanks !!!

Bringing metaphor down to earth and engaging it directly. Absolutely.

Thank you for this inspiring piece, David.

Wonderful essay. Thank you.