I believe that Urban Planning & Design (UP&D) should be considered a ‘Right’ and brought to public dialogue. The democratization of UP&D would be a significant step towards the achievement of just and equal cities. Exercising this right would be an effective means for bringing about much-needed socio-environmental change.

I believe that Urban Planning & Design (UP&D) should be considered a ‘Right’ and brought to public dialogue. The democratization of UP&D would be a significant step towards the achievement of just and equal cities. Exercising this right would be an effective means for bringing about much-needed socio-environmental change.

The impact of urban spaces on our lives is so enormous that it is necessary to focus on the planning and design undertaken by governments and various private agencies, planning that reshapes spaces continuously through time. As a matter of fact, planning and design can be effective democratic tools of social change and therefore must be brought to public domain and popularized in order to free it from the shackles of manifold control and exclusivity. Moreover, cities are built not merely with physical structures—buildings and infrastructure—but also with social and civic capital, for which building inclusive cities is a priority. Sadly, the two realms are polarized. Barriers between people and development decisions are continuously reinforced by sophisticated government policies and programs. This often leads to unacceptable and unsustainable growth with alarming social and environmental consequences.

Claiming urban planning and design rights has to be understood as part of larger movement for claiming “right to the city,” as much as other democratic rights movements, enshrined in law.

In India, for reasons that suit the policy makers and governments, UP&D are not considered important in defining the nature of cities. Instead, city building is driven by policies without any understanding or assessment of their impact on built-form. By claiming planning and design as a right, people across communities would no more be casually or cynically invited by governments to participate and respond to decisions after their formulation and announcement. Rather, they would have opportunities to engage in the process of decision making right from inception of plans, deciding the objectives and intent of proposals. This demand for planning and design rights goes beyond the generally accepted notion about the limitations of their right of participation.

Public perception in India is that planning requires exclusive knowledge and only few are capable. This must be de-mystified and expose its bluff. It is important for people to not merely respond to change but envision change. Most important, the democratization of UP&D would hopefully facilitate unification of the fractured cityscapes and heal deep social and cultural fissures.

Urban planning and design dialogue

In my own city Mumbai, where I have worked for many years as architect-activist, the exclusion and marginalization of the majority from development decisions has produced critical levels of social alienation and apathy. Meanwhile there has been unsustainable and anarchic growth of the city.

Today, citizen’s movements in many Indian towns and cities are actively engaged, not just in questioning the government’s plans, but also evolving people’s vision and alternatives for democratization. A notable example is Mumbai, where there are two important movements: the Open Mumbai plan, by this author; and the integration of slums into the development plans and programs of the city, by Nivara Hakk, an housing rights movement by slum dwellers. I have been a key participant in both these movements.

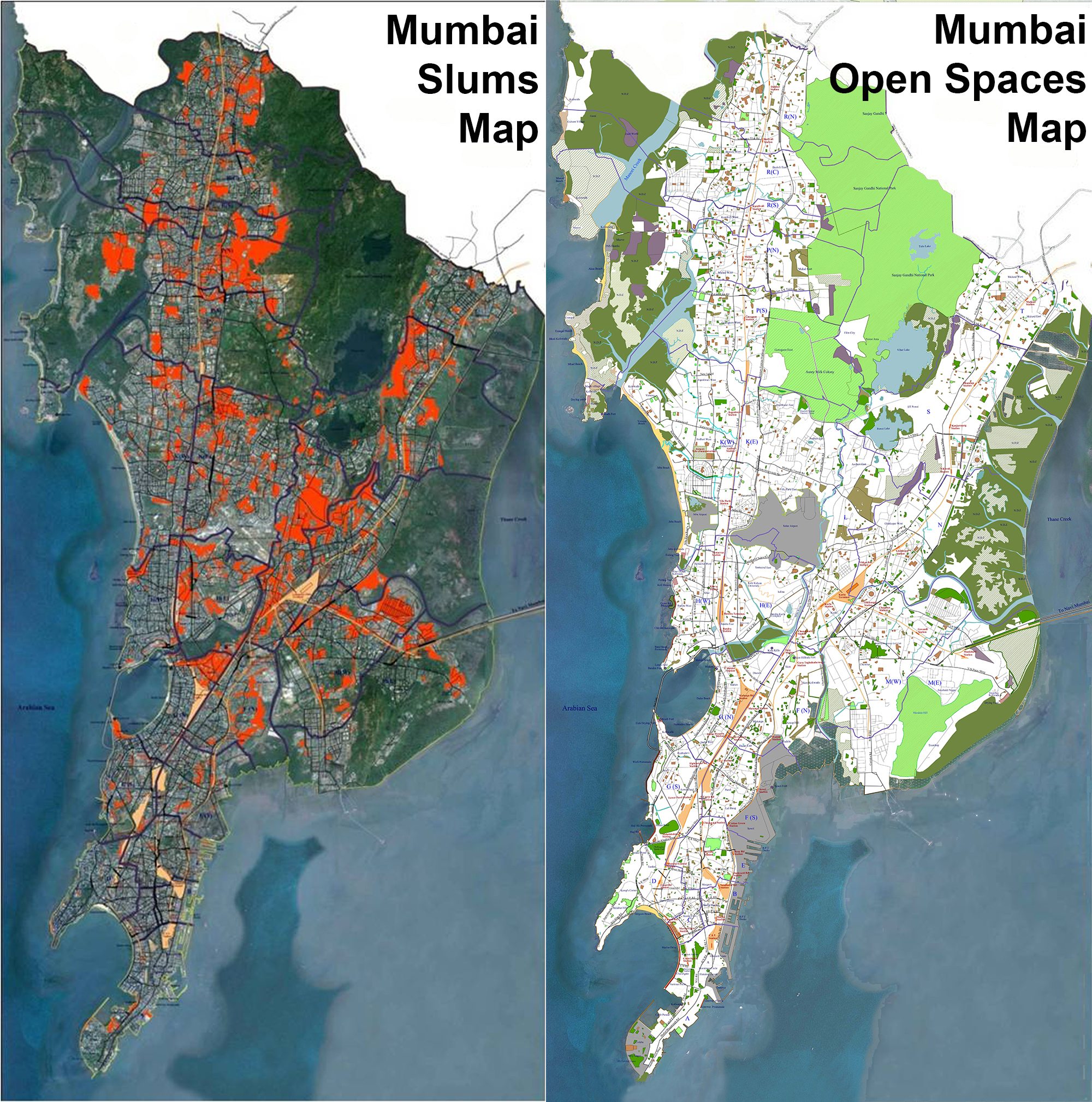

In Mumbai, close to 5.5 million people, constituting nearly 50 percent of the city’s population, live miserably in slums. They occupy just 8 percent of the cities developable land, living under traumatic high-density conditions, without adequate services, infrastructure or open spaces.

Over the years, through various sophisticated slum redevelopment policies, the slum lands are forcibly taken-over for free by private builders. Under this policy existing populations in slums are squeezed to one third of the land they occupied prior to redevelopment. The land reclaimed from slums is built over with expensive housing and commercial projects for sale in the open market. This development model is leading to further slummification of the city and worsening living conditions for slum dwellers. Displacement and dispossession continue to characterize slum clearance and redevelopment schemes. Tragically, there is no space and opportunity for participation and engagement of the slum dwellers in the redevelopment of their areas.

Slums proliferate in Mumbai because there is no construction or availability of affordable housing in the formal market, for both the poor and middle class people. Slums are spread widely, and mostly are informally located (i.e., without government sanction or planning), thus adversely affecting the quality of life and environment of the entire city. As a matter of fact, Mumbai, or Bombay as it was once and sometimes still is called, is referred to as ‘Slum-bay’ by many academicians and activists. A documentary film jointly produced in 1989 by the Indian Institute of Architects and the Commonwealth Association of Architects and co-directed by this author is titled Slum Bombay.

Yet Mumbai’s official development plan leaves them as blank areas, without documenting them, and a detailed mapping of the slums has been avoided over the years. For the first time the city got to see and realize the extent of slums across Mumbai is when this author and Nivara Hakk mapped the physical extent of slum land. This map showed that slums were substantial and contiguous. It exposed the myth that slums occupied most of the open spaces, reserved lands and large tracts of mangroves and other natural areas, posing serious threat to the environment of the city. This had been the incorrect claim of middle and upper class people.

More importantly, our mapping put forward a larger vision for slums redevelopment and their integration with the city. The need for comprehensive planning and design finally got acceptance in the government parlors and housing policy documents. The Slums Redevelopment Authority under the state government has now begun a detailed mapping exercise and is considering a new slums redevelopment master plan.

In one of the largest slum demolition and eviction drives in India, ordered by the court, a protracted struggle waged by the over 75,000 slum dwellers families (over 400,000 people) residing in the Sanjay Gandhi National Park. Nivara Hakk challenged the order, demanding rehabilitation first. Brutal attacks by the demolition forces of the government, deploying armed forces and helicopter surveillance, led to many homes being crushed and lives lost. After legal interventions, the court amended their order of eviction, proposing to the government to undertake rehabilitation of the eligible people at an alternate location and only then carry out demolition.

Nivara Hakk conducted this rehabilitation, successfully carrying out a participatory planning and design exercise, and organized the slum-dwellers into co-operatives at the new site for management and maintenance of their buildings and common areas. Today, more than 12,000 families proudly occupy their new homes.

On the other hand, Mumbai is a unique city having a vast and diverse extent of rich natural assets, covering nearly 240 km2, or approximately 50 percent of the city’s total area. These include, wetlands, mangroves, creeks, rivers, watercourses, creeks, hills, forests and beaches. Sadly, over the years, we have not only turned our backs on these valuable natural areas but have continued to abuse them. Rampant destruction of these sensitive areas over the years by land sharks and real-estate agencies has led to threatening environmental situations. Yet the development plan for the city does not document them in detail nor does it record their boundaries and areas. Through the “Open Mumbai” plan, we have demonstrated how creating open spaces all along the natural areas would enable their integration with the city, put them to daily life experiences and ensure their protection through citizens vigilance.

The lack of transparency in planning and urban land use demonstrated by these examples is a problem world over, as governments and their various agencies publish specific plans and projects for public knowledge and response, doing so with a set of severely imposed conditions. In many instances the relevance and need of the project itself is seldom open to question. Instead, they tend to engage the public with technical details with which most people cannot engage. As a result, only select individuals and groups respond with their suggestions and objections. Such a situation has lead to systematic exclusion of large sections of the public who are adversely affected by the very plans that should benefit them. For most people, their interaction and relationship with the city is limited, apparently by design of those in power.

A key objective of open dialogue in land use and planning is to inform and educate the public on the ideas, objectives and impact of various plans and development programs that are promoted not just by governments but also by powerful private agencies that have achieved specific development rights. This way people who are detached from the city can get closer to it. Ironically, urban design as a tool has been most often used to promote discriminatory and exclusionary practices, as in Mumbai and other Indian cities, operating within the confined and barricaded city spaces.

Values: a paradigm shift for cities

Today, planners and architects are operating within a web of contradictions. With market driven city builders being increasingly obsessed with construction turnover, they have come to consider designers as mere service providers. In turn most designers express very little or no concern for larger socio-environmental causes. The prevailing context of exclusion and discrimination, and the city’s fragmentation, along with environmental abuse, has to be radically altered towards the achievement of social and environmental unification. These objectives have to form the basis of urban planning and design programs, leading to a paradigm shift in the idea of cities and their built forms and structures. This shift requires going beyond the obsession with viewing cities only through the lens of financial valuation and into an assessment of socio-political and environmental economy.

Public dialogue ensures that governmental organisations and elected representatives are answerable throughout their tenure and not just during election period, turning urban development into a dynamic, vibrant and sustainable process.

Let’s review an example from Mumbai. Recently the Municipal Corporation and the state government put forward the new Draft Development Plan 2012-2032. The plan was clearly anti-people and detrimental to the ecology and environmental interests of the city. It avoided the question of slums redevelopment and their integration with the city, and proposed plans that would further cut down the meager open spaces. Mumbai has a miserable ratio of less than 1.5m2 per person open space. In comparison, London has 31.68, New York, 26.4, Tokyo, 3.96.

Citizens groups, NGO’s, workers, slum-dwellers and even the middle class organized public meetings in protest. Concerted effort to build public opinion forced the government to recall the plan and start the process all over again. Earlier appointed consultants for the preparation of the plan were terminated and the municipal corporation in charge of it is presently going through public hearings, evaluating over 50,000 suggestions and objections filed by individuals and organizations. Hopefully a more acceptable plan will emerge reflecting the development needs and demands of all the people.

Such participatory momentum needs to be sustained and expanded, not just in Mumbai, but also in all towns and cities across India, and today, there are such movements around the country. They are of vital importance.

Rights to concessions in a neo-liberalized world

From rights to concessions is yet another oppressive social and political trend that has come to prevail, particularly evident in the neo-liberalised world. Public freedom and rights over a wide array of issues that affect life in cities have been turned into matters of negotiation and concessions, leading to reductions in open space and little opportunity for public participation. Land deals are led by private agencies bargaining for concessions in monies and goods rather than engaging in issues of basic rights. It is only when there are people’s uprisings that the governments begin to grant fringe or peripheral benefits to the public under the guise of public largesse, without altering the very foundations upon which colonization, exclusivity and private empires are built across cities. Increasing commodification under expanding markets has engulfed basic social and human development needs, and has substantially eroded fundamental rights of most people.

But there is light at the end of the tunnel due to the innumerable rights struggles the world over. People’s collective’s are intervening and participating in the development and governance of public spaces, for example in movements to reclaim Mumbai’s waterfronts, led by various citizens groups along with this author. For management and governance of these waterfronts, a tri-partite between citizens, government and private agencies has been established with the residents association at the top of the pyramid.

Similarly, housing rights movements by Nivara Hakk has forced governments to reluctantly recognize land rights of the poor. But, policy after policy continues to doll out concessions to regulate people’s demands in measured doses, without altering the fundamental premise of permitting land grabs for real estate business interests by private agencies.

The way forward

Considering neighborhoods as the base for organising movements for effective democratization of UP&D is key. Such an approach facilitates local people’s active participation in matters concerning their area, which they know best, while influencing the city’s planning and development decisions.

Through a neighborhood-based development approach it would be possible to decentralize and localize projects and their designs, breaking away from mega-monolithic planning and design ideas with enormous investments that impose unbearable burdens on the lives of most people. Neighborhood based UP&D approaches would also facilitate closer interaction between people and their elected representatives. Importantly, neighborhood work creates a more collaborative approach to city and place making. The various movements reclaiming public spaces in Mumbai — the seafront development in Bandra; the Juhu beach redevelopment work; and the “Juhu Vision” plan with work along the watercourses called Irla Nullah — have amply demonstrated the gains of neighborhood based approaches to city development. For citizens, these projects have allowed the immediate reclamation, redesign and re-programming of public space.

With public space being the main planning criteria, we hope to bring about a social change: promoting collective culture and rooting out alienation and false sense of individual gratification promoted by the market. Our experience of neighborhood actions in Mumbai has come to confirm that such initiatives can influence long- term change in ways cities development is understood. Interventions by citizens, as in Bandra, Juhu and other areas of Mumbai, would have never been anticipated by a ‘master plan’ for the city.

Conclusion

Urban Planning & Design can be oppressive. But on the other hand it can be progressive and liberating. As city spaces have been fragmented and colonized, reflected in the growth of gated communities and other exclusive spaces, it is our challenge to use UP&D tools to network the disparate spaces and people into a cohesive and accessible city. It is only through active dialogue and participatory programs that individual, family and community relationships can be nurtured.

Claiming ‘urban planning and design rights’ has to be understood as part of larger movement for claiming “right to the city,” as much as other democratic rights movements, enshrined in law. To claim Urban Planning and Design rights is to assert peoples’ power over the ways in which our cities are created, with a determination to build socially and environmentally just and democratic cities.

P.K Das

Mumabi

The Just City Essays is a joint project of The J. Max Bond Center, Next City and The Nature of Cities. © 2015 All rights are reserved.

Leave a Reply