My vision for a just city is one where design and its power as a tool against inequality is leveraged for the benefit of all residents. As the director of design programs at the National Endowment for Arts, and one of the U.S. government’s primary advocates for good design, I spend a lot of time with mayors and other leaders advocating for the power of design. In the words of Charleston, South Carolina Mayor Joseph Riley, a mayor is “the chief urban designer” of his or her city. Even so, most mayors require education on what design can do—and what it cannot do.

My vision for a just city is one where design and its power as a tool against inequality is leveraged for the benefit of all residents. As the director of design programs at the National Endowment for Arts, and one of the U.S. government’s primary advocates for good design, I spend a lot of time with mayors and other leaders advocating for the power of design. In the words of Charleston, South Carolina Mayor Joseph Riley, a mayor is “the chief urban designer” of his or her city. Even so, most mayors require education on what design can do—and what it cannot do.

Why does design matter to the just city?

Yet there are forces of inequality that are outside design’s reach as a tool. A just city will have fairer tax and fee codes to balance community resources for all of its citizens. A just city will crack down on predatory lending and other detrimental banking practices. A more just city will have better paying jobs to help lift people out of poverty. A more just city will listen to the #Blacklivesmatter protestors and look at policies to address the unjust penal and policing system. None of those are design issues. Still, design can play a role. Here’s how:

Creating a better public realm: Mayor Riley likes to talk about how every citizen’s heart deserves to sing in public spaces. These are the spaces in the city that all of us own—the places where we can mix and build understanding across economic and racial barriers. It is vitally important that they are designed the right way, and often, they are not. How a building meets the street matters, the materials you use matter, and the scale and size of spaces and buildings matter. It has been proven that better designed streetscapes and public spaces typically have less crime, higher pedestrian activity and increased economic activity. If done correctly, public space can also have multiple other benefits too, such as the Main Terrian park in Chattanooga, Tennessee, which cleaned up a polluted site in a historically disadvantaged neighborhood (environmental justice benefit) and has public art that encourages exercise (public health benefits).

Many people (and NEA grantees) across the country are dedicated to making better public spaces. I advise you to go seek out their suggestions. It is important you empower not only the designer in the creation of public space but also the public at the same time.

Maintaining infrastructure: The maintenance of the designed part of cities, the buildings and infrastructure, matters. It shows respect for the entire public when you respect the public space. A just city is well-maintained across all of its neighborhoods. At the most basic level, the public infrastructure needs to work. Public water systems impact public health. Street lights lead to safety. It is all connected. Dr. Mindy Fullilove urgently talks about how the aging lead pipes in historically underserved neighborhoods are poisoning the children and holding them back in educational ability—maintenance matters. Even where you put flood infrastructure matters. In Fargo, ND, the huge drainage basins they built in response to the disastrous flooding of the Red River tore apart some of the most disadvantaged neighborhoods. To fix this mistake, they have used NEA funds to work with artists and designers to rethink the spaces as community commons for the neighborhoods—spaces to gather and be active that can also flood.

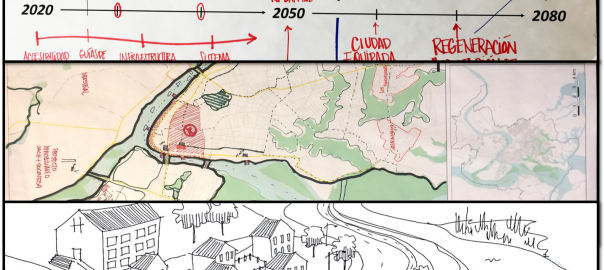

Improving connectivity: Transportation is a design issue. It helps determine street life, walkability and much more. Because of the gentrification of strong market cities and the hollowing out of the inner core of weak market cities, many lower income people have moved to the first ring of suburbs, which are often poorly served by public transit. This trend means if they do not have cars, they are unable to easily access the economic centers of their community. Some cities are responding to this trend better than others. In Atlanta, there are stories of people taking Uber to the nearest bus line because it is not walkable. Whereas in Houston, the city is redoing all of its bus lines—literally throwing out the map and starting over – in order to better serve lower income residents. What it all boils down to is people need to be able to get to jobs, and not everyone can afford a car and gas. If we want to create accessible cities with economic opportunity for all, we must design better transportation systems.

Zoning for progress: There may be no topic more important to urban designers and more impenetrable to the public than zoning. These are the laws that regulate land use in most of America. They must be modernized if we want to build thriving, inclusive neighborhoods. Too many communities try to work within outdated regulations instead of tackling the issue head on, or they use zoning as a way to keep existing power systems in place—regulating affordable housing out of communities, for instance. It is a tool that must be used carefully though, as evidenced by the recent backlash to the rezoning plans in New York City. The intention was to help the market build more affordable housing, but instead the plans have led to a gold rush of speculation of the existing properties and begun to price out longtime residents.

Engaging all residents: Residents must be part of the urban design process. They must not only demand good design but also support and reward it. History has shown good design does not happen without public input. Most of the design people I know who care about inequality are asking important questions right now: When does design matter to the civic engagement process? How can it give voice to the previously unheard or underserved? How can design help them take control of the development decisions in their own neighborhoods? We at the NEA are working with field partners to expand on what we already know: designers can help residents see what proposed change could look like sooner rather than later through temporary or inexpensive installations, and design processes can help residents envision their own future in inventive ways. I suggest you check out the work of the Kounkuey Design Initiative in the Coachella Valley in California to get a sense of what design can do to engage and give voice to residents. They are one of many designers working in this space.

Experiment: We all know that there is limited funding out there to support our cities. To combat this, be experimental. Try small things. There has been an explosion of “tactical urbanism”—a fancy term for small temporary projects—happening across the nation in which designers and others act on their own initiatives to solve urban problems. Parking Day is one example of such works—it’s when people create a temporary park in a parking space. While some probably think these projects do not address the big issues needed to be addressed in a just city, I have seen many of them impact their communities in important ways, such as the Market Street Prototyping Festival in San Francisco, in which the Planning Office is using temporary experiments to learn about what works before they undertake a massive rebuilding of the street. We’re seeing experiments all over the place and in unexpected places—take the work of Emily Roush-Elliot, an Enterprise Rose Fellow working closely with residents of Greenwood, MS. As a first step to engage this historically disadvantaged African-American community, Emily and her co-workers took a muddy lot and, using a few concrete pavers and some benches, created a small new park. This space brought residents out of their homes to discuss housing and economic needs and set forward a whole series of activities that are chipping away at years of disinvestment and distrust. Inequality will die from a thousand cuts, not a silver bullet.

Don’t forget about beauty: Aesthetics are subjective, but good design is not. In 2010, the Knight “Soul of the Community” study investigated just why people move somewhere. It asked the question: “Great schools, good transit, affordable health care and safe streets all help create strong communities. But is there something deeper that draws people to a city—that makes them want to put down roots and build a life?” After interviewing more than 40,000 residents over three years, the top three answers for why someone loves living in a place shocked almost everyone—they are “social offerings, openness, and aesthetics.” Doesn’t a just city build the place that people want to love? Don’t all residents deserve beauty? Many people have made the case as to why beauty is a tool for justice—the most famous being Elaine Scarry in her landmark work “On Beauty and Being Just.” While it is a must read, I do prefer the TED talk of another author in this series, Theaster Gates, who, amongst other ideas, makes a great case for how beauty begets beauty; beauty is a positive beacon shining a light to show that change is possible, and hence beauty can change how people act.

Design Matters

Remember, design is a tool—not a solution. It is imperative that when trying to build a more just city you remember the anthropological history of a place and understand what has shaped it up to this point. Any leader or resident or designer must dig into the history of a place and look at the policies that have shaped it. If you do that and use the tools of design the right way, I am convinced that design will matter, that engaging smart designers will help as we try to bend the arc of history towards just cities.

Jason Schupbach

Washington

The Just City Essays is a joint project of The J. Max Bond Center, Next City and The Nature of Cities. © 2015 All rights are reserved.

Hi Jason,

Really appreciate your understanding about city development. A very well articulated write up covering most of the aspects for city development. I am Huzoor Choudhry from

India, am a free lance designer working with the local Government authorities for Cultural based city development, also am a fellow member of The British Museum London and have been doing work on visitor visual experience for museums in Egypt (in collaboration with BM London). So, i design & manufacture cultural art installations & various other urban requirements for cities in India.

Regards

Huzoor Choudhry

Hi Tyler,

Agreed! Thanks for your comments and kind words!

best,

Jason

Hi Alexandria,

Thanks so much for your comment and your kind words. We’re working all the time to support designers (and artists) role in creating a more equal world. You might want to check out our work on ‘social impact design’ available here: https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/Design-and-Social-Impact.pdf

It covers a lot of the issues that have come up in the questions you asked.

Feel free to reach out to me with any follow up questions – [email protected]

best,

Jason

Jason,

A great essay and, as an architect, it is a refreshing point of view to read. I certainly agree with all of your bullets, but I’ll add that I think your words underscore the idea that “design” supports an idea of influence and capability in our built environments and all that they influence (which as you point out, is almost everything). I find that we, as a culture, have a tendency to get caught up in the (admittedly strong) inertia of “how things are done” or “the way it is.” While not inconsequential, these boundaries can be more mental than physical. Designers, along with the communities they support, have the capacity to change the course of our realities. While far from easy, positive evolution is certainly within our grasp.

Thanks Again-

Tyler

Thank you for your essay, it was interesting to hear the point of view of a practitioner. I particularly enjoyed your sections on the importance of beauty and experimental design.

As you say, design is a powerful tool. However, design can be a powerful tool for creating both equality and inequality, as you demonstrated through the example of the drainage basin in Fargo, North Dakota. In your experience have you found it difficult to negotiate the creation of design that promote equality over inequality, of design that is created with intentionality, and that addresses real issues?

Thank you for your essay!