(Una versión en español sigue inmediatamente después.)

“We must remember that what we observe isn’t nature itself, but rather nature exposed to our method of questioning and perceiving.”

—Werner Heisenberg

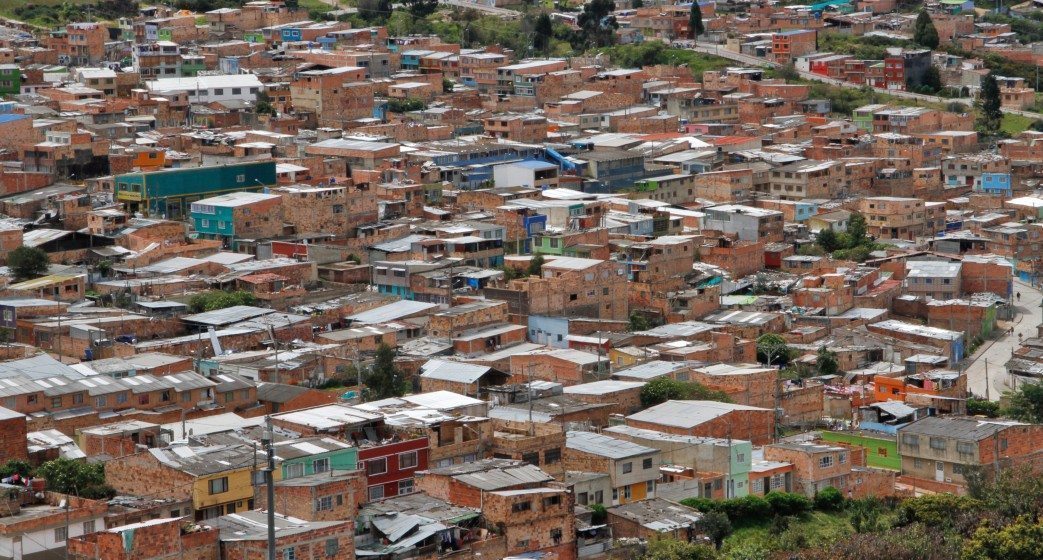

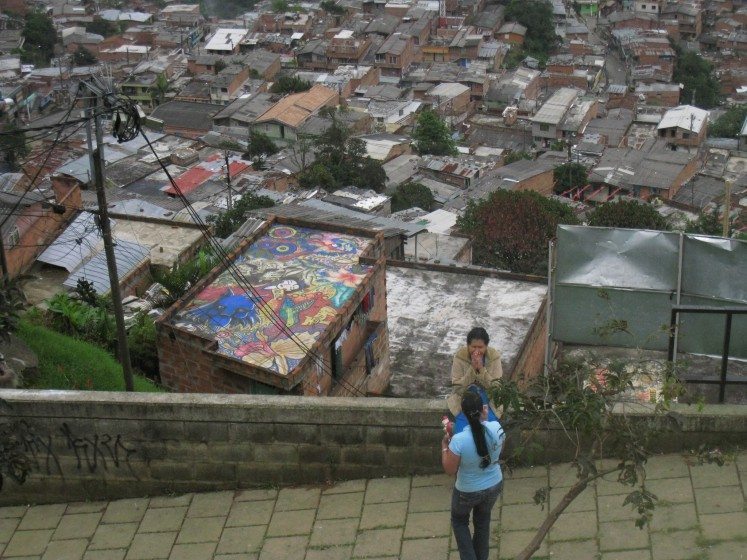

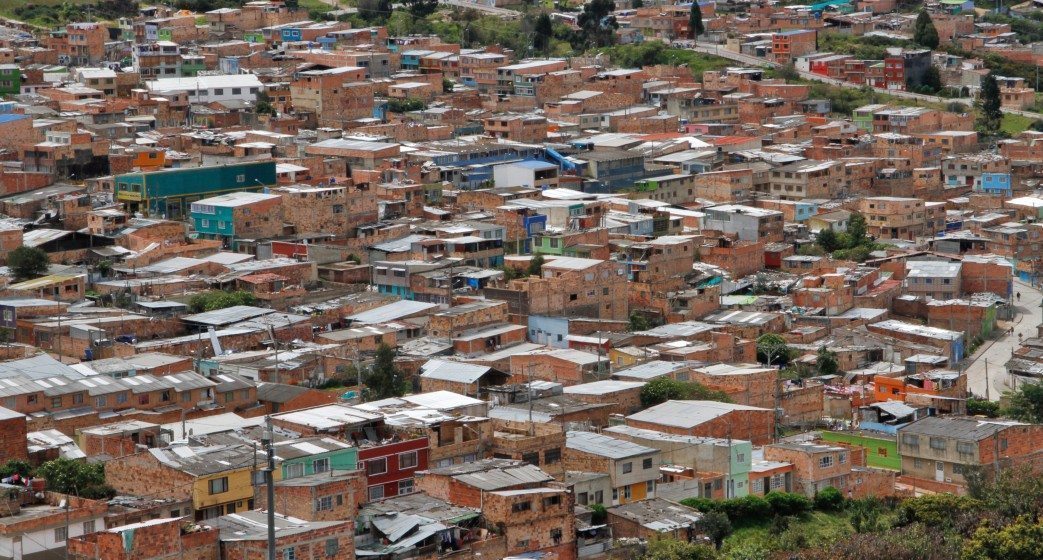

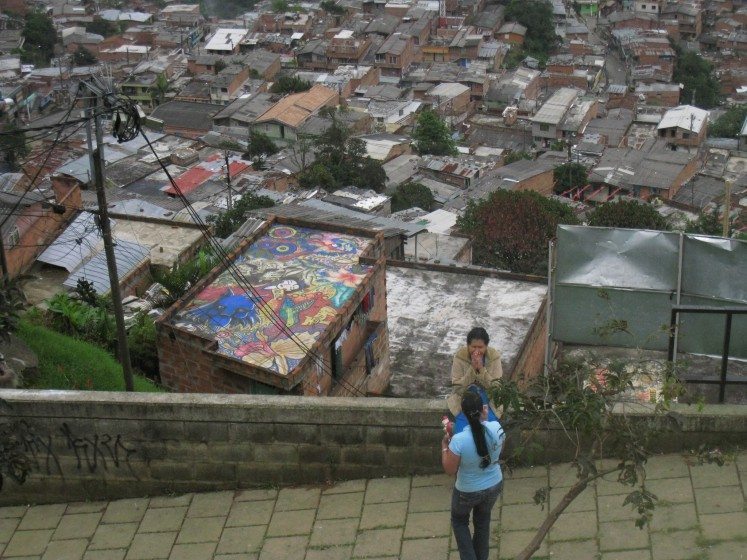

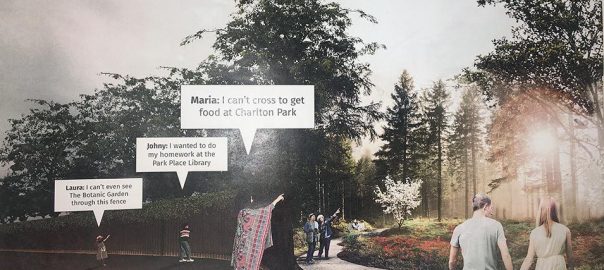

In order to talk about sustainability on an urban level, it is fundamental to have an understanding of the social particularities produced by the historical, economic and cultural context of the territories that belong to each urban center. In Latin American cities, informal growth has primarily occurred due to population displacement from rural areas to large, attractive cities that offer more promising economic and job opportunities. In Colombia’s particular case, both the internal armed conflict and scarcity associated to environmental phenomena, such as water shortages, have greatly contributed to the forcible transfer of whole, and disintegrated families, to places that supposedly offer greater security and stability: large cities where, apart from the above mentioned advantages, there’s better access to government institutions.

Conversations on sustainability are dominated by specialized groups that study these processes, seeking solutions and answers, but this has to change.

Along with people displaced by conflict, other people who don’t have access to urban land settle in the city’s periphery, creating out of control, human settlements in which a “natural” and unplanned urban expansion takes place, shaped by its inhabitants. These informal growth areas coincide, not by chance, with the city’s most marginal areas, given that land occupation along the urban periphery has occured in places with difficult access because of strong geographical features like hillsides, river banks, and very steep slopes; areas with no infrastructure and on the fringes of legality, for according to policy, these are unbuildable lands. All of this makes these places highly susceptible to environmental and geological risks such as landslides, forest fires, and floods, among others (Motta C., Sobotova L. 2015).1

Inequality prevails in Latin American cities, and 57% of the population that lives in poverty is employed by the informal sector.2 In this sense, in cities where the informal economy seems to be a common denominator, it’s essential for an integral concept of sustainability to reach everyone, for in the face of urban expansion in which there is minimal planning, neighborhood authorities and residents become responsible for the environmental management of their place and its landscape.3

Currently there are multiple proposals revolving around the discourse of sustainable cities, in which green infrastructure systems are implemented and natural resources are protected to guarantee ecosystem service supply. This discourse, however, is concentrated among scholars, specialized professionals, and a limited percentage of the population. As a result, city planning and its corresponding sustainability proposals are far removed from the people who are building their spaces in terms of trends, as other groups that have settled in these territories have done before them, without taking into account water, vegetation, or open space. Instead, their logic privileges survival and permanence on the land.

In Colombia, small villages in geographic locations where the population is diverse, access is difficult, and the topography is unstable, have been influenced by models of public space transformation found in more densely populated cities like Bogota or Medellin. In Bogota this is evinced in a tendency toward hardened spaces, away from the application of environmentally friendly infrastructure, so although the amount of public space has increased, its quality and its environmental and ecological functions continue to be a challenge. Thus, in cities located in the Amazon, like Leticia and others, we find examples of public spaces that are far from the particular social and climatic context of the place.

This problem is related to a much greater one, which is that in Latin America, public space is still associated with occupied, impermeable space. An example of this is the transformation of many streets into pedestrian thoroughfares, which in terms of prioritizing people over cars is a great advance. But in environmental terms, very few considerations are applied, except for the planting of trees.

Photo: Desiderio Martínez

Cities like Monteria, in Cordoba, show that there are important exceptions. There was an evident appropriation of the riverbank by the community, so when the Mayor’s Office started planning its recovery, and with the people’s collaboration, the forest was preserved and a common space was created for the promotion of social welfare and cohesion processes, even though none of this was included in the urban sustainability principles.

In this case, many concepts that seem limited to experts, but that are actually part of the community’s daily life, are put into practice. Some of these concepts are: resilience, biodiversity management, climate change, sustainability, low impact development, ecosystem services and green infrastructure, among others.

| Biodiversity: according to the United Nation’s Environmental Program (UNEP – WCMC, 2013) the word biodiversity is a compound word derived from the term ‘biological diversity.’ Diversity is a concept that refers to variations or differences within a range of entities; biological diversity therefore refers to variety in the living world.

Climate change (FCCC usage): a change of climate, which is attributed directly or indirectly to human activity that alters the composition of the global atmosphere and which is in addition to natural climate variability observed over comparable time periods. (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – IPCC) Ecosystem Services: this concept refers mainly to the cultural or economic benefits people receive from the ecosystem.4 Green, or Ecological Infrastructure: a network of strategically planned natural and semi-natural spaces and other environmental elements designed and managed to offer a wide range of ecosystem services. This includes green and blue areas, the latter corresponding to aquatic ecosystems, and other physical elements in natural, rural, and urban terrestrial and marine areas. (Conama 2014) Green infrastructure uses vegetation, soils, and natural processes to manage water and create healthier urban environments. The scale of green infrastructure ranges from urban installations to large tracts of undeveloped natural lands and includes rain gardens, green roofs, urban trees, permeable pavements, rainwater harvesting, wetlands, protected riparian areas, and forests. (Environmental Protection Agency – EPA) |

Integrated Biodiversity Management: process through which actions for the conservation of biodiversity and its ecosystem services, such as knowledge, preservation, use and restoration, are planned, implemented and monitored in a specified social and territorial scenario with the purpose of maximizing social welfare by maintaining the adaptive capacity of socio-ecological systems on a local, regional and national scale. (Alexander Von Humboldt Institute)

Low Impact Development: works with nature to manage stormwater as close to its source as possible. LID employs principles such as preserving and recreating natural landscape features, minimizing effective imperviousness to create functional and appealing site drainage that treat stormwater as a resource rather than a waste product. (Environmental Protection Agency – EPA) Resilience: “the capacity of a system, be it an individual, a forest, a city or an economy, to deal with change and continue to develop. It is about how humans and nature can use shocks and disturbances like a financial crisis or climate change to spur renewal and innovative thinking.” (The Stockholm Center of Resilience)5 Sustainability: making use of resources without depleting them. Sustainable development: development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. (Panel on Climate Change – IPCC.) 6 Transformational Adaptation: “a process through which fundamental attributes of a system are changed in response to the climate and its impacts.” (IPCCC 2014) |

On one hand, the terms above must be simplified in order for the people who live and build informally to understand them, and on the other, there must be a recognition and examination of existing practices that represent these concepts in informal settlements. The informal neighborhoods located on Bogota’s Eastern Mountains are important examples to consider. This mountain range is a 32,124-acre (13,000 hectare) forest reserve thanks to the wealth of its biodiversity and water sources, and it’s the city’s Eastern natural boundary. There are very heterogeneous neighborhoods here, with privileged sectors as well as and informal settlements. In the latter, representing marginal parts of the city, there are examples of social organization in which proposals with sustainable intentions are visible.

Specialists should work more closely with the population, not just during consultations, but through entire processes, and they should be more receptive in learning about people’s day-to-day risk management strategies and environmental problems that are framed by sustainability.

One of the clearest and most widespread practices is the use of local, communal aqueducts, which in the absence of a proper water supply and sewage system, make use of the mountain’s ecosystem services. In this sense, taking care of the water sources becomes directly related to sustenance, which is why these processes are related to the recovery, use, and care of the streams, another important practice that has taken place in the mountains, and the need for a sustainable use of natural resources is evident. There are additional interests linked to environmental protection and maintenance, such as projects that stimulate mountain use by civilians and increase the city’s public space. Agroparque los Soches, Parque Entre Nubes, and Reserva de la Sociedad Civil del Umbral Cultural Horizontes, among other parks and reserves, represent the possibility of the Eastern Mountains becoming a benchmark for the concepts presented here, not just for the mountain dwellers, but for every citizen.

The acknowledgement of existing practices in the Eastern Mountains brings to light how the communities faced with the greatest environmental challenges appropriate the experts’ terminology. Their location, on the Reserve’s border, makes their impact on the ecosystem even greater, and exhibits unique relationships to the environment. Although formal and informal construction in these territories must be suspended, working together with informal settlements is crucial for a sustainable city to exist. Thus, the discourse by scholars and experts must have a greater dialogue and exchange in local settings.

Ecobarrio Villa Rosita. Photo: Diana Wiesner

Ecobarrio Villa Rosita. Photo: Diana Wiesner

The discussion on the democratization of conversations about sustainability is now open; as an example:

| Biodiversity Management: Placing value on the variety and differences of living beings and promoting healthy relationships among them. | Resilience: Ability to recover from something.

Risk Management: What mothers are permanently doing with their kids. |

| Climate Change: Climate changes that have become standard. | Sustainable: That which can be sustained in time. |

| Ecosystem Services: Benefits we get from nature, such as food, water and recreation.

Green Infrastructure: Water – nature sensitive design. |

|

In order to achieve participatory processes in Bogota’s Eastern Mountains, we propose the promotion of pacts with the land and among neighbors, which include proposals for friendly behavior and best practices with the environment. This is how the Mountains of Bogota Foundation promotes the pact with the mountains, from each individual inhabitant of the region.

These pacts pursue the restoration of our relationship with nature, and the teachings of inhabitants of rural areas who live together with risk, and seek to teach common sense practices that respect life cycles. For this to take place, citizens must reconnect with the discovery of what’s simple and vital, using concepts such as “the common good” in order to produce ethical and socially responsible day-to-day behaviors with the environment.

Regarding public policies, there are indicators that measure a city’s environmental impacts, such as: proximity, equality, amount of public space in area of influence, pedestrian accessibility, and public safety. It’s important for these best environmental practices to become part of public policy. Equally important is the consolidation of the landscape as a common asset, as well as the implementation of new quality indicators, such as the “resilience indicators of the soul” proposed by Professor Wilches.

From the voice of a country preparing for a time of post-conflict, it’s essential to aim at building communities that appropriate an eco-friendly culture, as well as to acknowledge, from a human perspective, existing environmental practices in different urban settlements in order to strengthen the dialogue that will allow for a real transformation, with the public’s participation, of the landscape.

Diana Wiesner

Bogotá

Notes:

2 — Patricio Zambrano Barragan. IADB (Inter-American Development Bank,) Resilient, Inclusive and Innovative Cities. International Symposium on Urban Ecology, Bogota, 2015.

3 — This is not an attempt to promote or foster informal land occupation, but rather a search to generate solutions for habitation models in said areas.

5 — http://www.stockholmresilience.org/21/research/research-news/2-19-2015-what-is-resilience.html

6 — https://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/glossary/ipcc-glossary.pdf

* * *

Democratización de conceptos hacia la resiliencia desde el alma

“Tenemos que recordar que lo que observamos no es la naturaleza en sí misma, sino la naturaleza expuesta a nuestro método de cuestionamiento y percepción” — Werner Heisenrberg

Para hablar de sostenibilidad a nivel urbano, resulta fundamental entender las particularidades sociales, producidas a partir del contexto histórico, económico y cultural de los territorios pertenecientes a cada centro urbano. Dentro de las ciudades latinoamericanas el crecimiento informal se ha dado principalmente por un desplazamiento de la población desde zonas rurales hacia grandes urbes atractivas, principalmente por ofrecer oportunidades más prometedores respecto a su producción económica y oferta laboral. Particularmente, en el caso colombiano, el conflicto armado interno, así como escasez asociada a fenómenos ambientales tales como carencia de agua ha contribuido fuertemente al traslado forzoso de familias enteras, o desintegradas, hacia lugares que ofrezcan “supuestamente” una mayor seguridad y estabilidad, es decir, grandes ciudades, en donde, además de las ventajas anteriormente planteadas, tienen mejor acceso a instituciones gubernamentales.

Las conversaciones sobre la sostenibilidad esta dominada por grupos especializados que estudian estos procesos y buscan encontrar soluciones y respuestas, pero esto tiene que cambiar.

Al igual que las personas desplazadas por el conflicto, diferentes personas que no pueden acceder al suelo urbano, se asientan en la periferia de la ciudad, conformando fenómenos de asentamiento humano “sin control” en los que se da una expansión urbana “natural” y poco planificada hecha por los propios habitantes. Estas zonas de crecimiento informal coinciden, no fortuitamente, con los lugares de mayor marginalidad en la ciudad, pues la ocupación de lotes en la periferia urbana se ha dado en zonas de difícil accesibilidad y servicios por la presencia de fuertes accidentes geográficos como laderas, bordes de ríos, pendientes muy inclinadas, entre otros sectores sin infraestructura y al margen de la legalidad debido a que son zonas no construibles según las políticas de suelo. Lo anterior, hace de estos espacios altamente susceptibles a riesgos ambientales y geológicos como deslizamientos, incendios, inundaciones, entre otros (Motta C., Sobotová L. 2015).

Las ciudades en Latinoamérica predomina la desigualdad y el 57 % de la población que vive en situación de pobreza esta empleado en el sector informal. En este sentido, ciudades en donde la informalidad parece ser el común denominador, resulta fundamental que el concepto integral de sostenibilidad debe llegarle a todos, pues, de cara a procesos de expansión urbana con baja planificación, son los agentes y habitantes de los barrios quienes se vuelven responsables por la gestión ambiental de su lugar y paisaje.

En la actualidad es posible encontrar múltiples propuestas en torno al discurso de ciudades sostenibles, en los cuales se implementen sistemas de infraestructura verde y se protegen sus recursos naturales para garantizar la oferta de servicios eco sistémicos. Sin embargo, este discurso se encuentra concentrado entre los académicos, los profesionales especializados y un porcentaje limitado de población.

Producto de ello, los términos en los que se planea la ciudad, y sus respectivas propuestas sostenibles, resultan alejados de las poblaciones, las cuales están construyendo sus espacios de manera tendencial como lo hacen otros grupos asentados en el territorio, sin contemplar temas como el agua, la vegetación o el espacio libre. A cambio, se privilegian lógicas de supervivencia y permanencia en el territorio.

En el caso de Colombia, las pequeñas poblaciones localizadas en lugares geográficos de población diversa, difícil acceso y topografía inestable han estado influenciados por los modelos de transformación de lo público, como se observa ciudades de mayor densidad como Bogotá o Medellín. En Bogotá, lo anterior se ha evidenciado en una tendencia hacia espacios endurecidos y alejados de la aplicación de infraestructuras ecológicas, por lo cual, si bien el Espacio Público ha aumentado en cantidad, la calidad de su función ecológica y ambiental sigue siendo un reto. Por tanto, ciudades localizadas en el Amazonas, como lo es Leticia y otras ciudades aparecen ejemplos de espacios públicos , que no corresponden a su contexto social, geográfico y climático .

Esta problemática se asocia a una escala mayor, pues el Espacio Público en Latinoamérica todavía se asocia con la connotación de espacio construido e impermeable. Un ejemplo de ello es la peatonalización de varias vías vehiculares para el disfrute peatonal, que en términos de la priorización del peatón sobre el vehículo automotor, es un gran avance, pero en términos ambientales se aplican muy pocas consideraciones, salvo la inclusión de la arborización.

Ciudades como Montería, Córdoba, muestra que existen excepciones importantes. Allí, se evidenciaba una apropiación de la ronda del río, lo cual permitió que al momento de plantear una recuperación de la ronda por parte de la Alcaldía e integrando a la población, se velara por mantener la arborización del lugar y por generar un espacio en común que promoviera el beneficio social y los procesos de cohesión, a pesar de que esto no estuviera planteado dentro de los principios de sostenibilidad urbana.

En este caso, es posible observar que se ponen en práctica múltiples conceptos que parecen limitados a los expertos, pero que en realidad hacen parte del cotidiano de las poblaciones. Algunos de estos conceptos son: resiliencia, gestión de biodiversidad, cambio climático, sostenibilidad, desarrollo de bajo impacto, servicios ecosistemicos, infraestructura verde, entre otros.

| Adaptación transformadora:

“Es un proceso capaz de cambiar los atributos fundamentales de un sistema, en respuesta al clima y sus impactos”. IPCCC 2014 Biodiversidad: Según el Programa Ambiental de las Naciones Unidas (UNEP- WCMC, 2013) la palabra biodiversidad es una contracción del término diversidad biológica. Diversidad es un concepto que refiere al rango de variación o diferencias entre un rango de entidades; de manera que diversidad biológica refiere a la variedad dentro del mundo viviente. |

Infraestructura verde- Infraestructura ecológica:

Red estratégicamente planificada de espacios naturales y seminaturales y otros elementos ambientales diseñados y gestionados para ofrecer una amplia gama de servicios ecosistémicos. Incluye espacios verdes (o azules si se trata de ecosistemas acuáticos) y otros elementos físicos en áreas terrestres (naturales, rurales y urbanas) y marinas* (Conama 2014) |

| Climate change (FCCC usage)

A change of climate, which is attributed directly or indirectly to human activity that alters the composition of the global atmosphere and which is in addition to natural climate variability observed over comparable time periods. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Desarrollo de Bajo Impacto: works with nature to manage stormwater as close to its source as possible. LID employs principles such as preserving and recreating natural landscape features, minimizing effective imperviousness to create functional and appealing site drainage that treat stormwater as a resource rather than a waste product. La Agencia de Protección Ambiental (Environmentral Protection Agency -EPA). |

Resilience: is the capacity of a system, be it an individual, a forest, a city or an economy, to deal with change and continue to develop. It is about how humans and nature can use shocks and disturbances like a financial crisis or climate change to spur renewal and innovative thinking.” The Stockholm Center of Resilience

Sostenibilidad: A diferencia de la sustentabilidad, implica el aprovechamiento de los recursos sin agotarlos. |

| Green infrastructure uses vegetation, soils, and natural processes to manage water and create healthier urban environments. The scale of green infrastructure ranges from urban installations to large tracts of undeveloped natural lands and includes rain gardens, green roofs, urban trees, permeable pavements, rainwater harvesting, wetlands, protected riparian areas, and forests. La Agencia de Protección Ambiental (Environmentral Protection Agency -EPA). | Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) |

| Gestión Integral de Biodiversidad: Proceso por el cual se planifican, ejecutan y monitorean las acciones para la conservación (conocimiento, preservación, uso y restauración) de la biodiversidad y sus servicios ecosistémicos, en un escenario social y territorial definido con el fin de maximizar el bienestar social, a través del mantenimiento de la capacidad adaptativa de los socio-ecosistemas a escalas locales, regionales y nacionales. Instituto Alexander Von Humboldt | Servicios eco sistémicos:

This concept refers mainly to the benefit that people receive from the ecosystem, if they are cultural or economic. |

Los términos anteriormente planteados requieren por un lado, que se dé una simplificación del lenguaje para los agentes que habitan y construyen informalmente el territorio, y por otro, que se reconozcan y se examinen las prácticas existentes en los asentamientos que representan los conceptos anteriormente mencionados. Un ejemplo importante para ello es el caso de los barrios de origen informal ubicados en los Cerros Orientales de la ciudad de Bogotá. Esta cadena montañosa se constituye como una Reserva Forestal de más de 13.000 hectáreas debido a su riqueza en biodiversidad y fuentes hídricas, y representa el límite natural al oriente de la ciudad. Allí se encuentran barrios de enorme heterogeneidad social, pues es posible encontrar tanto sectores muy privilegiados como asentamientos de origen informal. En estos últimos, que representan zonas marginadas de la ciudad, es posible hallar ejemplos de organización social que se visibilizan algunas propuestas con intenciones sostenibles.

Los especialistas, por una parte deberían trabajar mas cercanos a la población, no solamente en consultas sino durante todo el proceso y ser mas receptivos en aprender igualmente sobre los procesos cotidianos de resolución del riesgo o de problemática ambiental que la propia gente realiza y que se enmarcan dentro de la sostenibilidad.

Uno de las prácticas más claras y reiteradas es el caso de acueductos veredales y comunitarios que, ante la ausencia de un servicio de acueducto y alcantarillado, han logrado hacer uso de los servicios eco sistémicos de la montaña. En este sentido, el cuidado de las fuentes hídricas se convierte también en un interés directamente relacionado con la subsistencia, razón por la cual estos procesos vienen relacionados con la recuperación, uso y cuidado de las quebradas, otra práctica importante que se ha dado en el territorio de Cerros, evidenciando una necesidad de hacer un uso sostenible por los recursos. Adicionalmente, ligado al cuidado del entorno y el mantenimiento del mismo, vienen otros intereses, como la creación de proyectos que fomenten el uso de la montaña y aumenten el espacio público de la ciudad. El Agroparque los Soches, el parque Entre Nubes, la Reserva de la Sociedad Civil del Umbral Cultural Horizontes, entre otros, han representado la posibilidad de que los Cerros Orientales se conviertan en referentes de los conceptos planteados para la sociedad civil y no sólo para quienes habitan en los Cerros.

El reconocimiento de las prácticas existentes en los Cerros Orientales muestra la manera como los términos usados por los expertos se apropian y se usan en las poblaciones que precisamente encuentran mayores retos ambientales. Su ubicación en el límite de la reserva hace que su impacto con el ecosistema sea aún mayor, presentando maneras particulares de relacionarse con el entorno. Si bien la construcción formal e informal en estos sectores debe suspenderse, el acompañamiento y participación por parte de asentamientos informales es fundamental para tener ciudades sostenibles, lo cual implica que los discursos académicos y de expertos tengan un mayor diálogo e intercambio en escenarios locales.

Se abre la discusión a simplificar los términos como ejemplo:

| Cambio climático: Cambios en el clima que se han vuelto cotidianos. | Resiliencia: Capacidad de recuperarse de algo. |

| Gestión de la biodiversidad: Valorar la diferencia y variedad entre seres vivos y promover sus relaciones saludables. | Sostenible, es lo que se puede sostener en el tiempo. |

| Gestión del riesgo: Lo que las madres hacen permanentemente con sus hijos. | Servicios eco sistémicos: Los beneficios que da la naturaleza como alimentos, agua y recreación. |

| Infraestructura verde: Diseños sensibles con el agua y la naturaleza. | Sustentable: lo que se sostiene a sí mismo. |

Para lograr procesos participativos en los Cerros Orientales de la ciudad de Bogotá se propone promover los pactos con el territorio y con los vecinos, dentro de los cuales se promuevan propuestas de comportamientos amigables y buenas practicas con el lugar, es así como ejemplos locales la Fundación Cerros de Bogotá promueve el pacto con los cerros desde cada habitante de la región.

Estos pactos buscan restituir la relación con la naturaleza, aprender de la población de las zonas rurales, que convive con el riesgo y enseñar prácticas de sentido común que respetan los ciclos de vida. Para ello, es fundamental volver a conectar al ciudadano con el descubrimiento de lo simple y lo vital, valiéndose de herramientas como la inclusión del concepto de “bien común”, con el fin de que se genere un comportamiento ético y social responsable con el medio ambiente en la cotidianidad.

En cuanto a políticas públicas, es posible encontrar indicadores que dan referencia acerca de los impactos ambientales de una ciudad, tales como proximidad, equidad, cantidad de Espacio Público próximo a su población de influencia, accesibilidad peatonal y seguridad ciudadana. Sin embargo, es importante que éstos se conviertan en una política pública de buenas prácticas ambientales, de la misma manera que consolidar el paisaje como un bien común y hacer uso de otro tipo de indicadores de calidad como los que propone el profesor Wilches: “los Indicadores de resiliencia desde el alma”.

Desde una voz de un país que se prepara para un “posconflicto” es fundamental apostar a construir comunidades que se apropien de una cultura ecológica, así como reconocer, desde lo humano, las prácticas ambientales existentes de los diferentes asentamientos urbanos con el fin de fortalecer un diálogo que permita lograr una real transformación del paisaje con participación pública.

Diana Wiesner

Bogotá

Sobre The Nature of Cities

Notas:

2 — Patricio Zambrano Barragan. BID, Ciudades resilientes, inclusivas e innovadoras. Simposio Internacional de Ecología Urbana, Bogotá. 2015.

3 — Con esto no se pretende promover ni fomentar la ocupación informal del territorio, sino que se busca generar soluciones a los modelos de habitación en dichas zonas.

5 — http://www.stockholmresilience.org/21/research/research-news/2-19-2015-what-is-resilience.html

Leave a Reply