A review of Ecodesign for Cities and Suburbs, by Jonathan Barnett and Larry Beasley. 2015. ISBN: 9781610913393. Island Press, Washington. 280 pages. Buy the book.

This book has an unashamedly strong emphasis on the city of Vancouver as a model—a city that has taken a leadership role. “Hundreds of thousands” of people involved in designing the overall plan, as well as area plans for its inner city, with the city government facilitating “a widely supported vision.” Whilst understandably proud of Vancouver’s achievements, the authors are not blind to its problems and acknowledge that the city “still has big sustainability and livability issues.” This awareness is a strength of the perspective offered in this book.

Barnett and Beasley provide a considered and well-articulated description of the problems of modernist zoning that have done so much to destroy the best qualities of urbanism, allied with articulate descriptions of solutions to urban development that are now a well-nigh universal litany (though still observed more in the breach than in substance, thanks to the massive momentum of the motorised modernist miasma).

Six axioms

The book’s six chapters build on four themes:

- Adapting to climate change

- Balancing transportation modes

- Replacing outmoded regulations and incentives

- Reshaping the public domain

Although this is not primarily a theoretical tome, the authors begin by considering the basic axioms, philosophy and ethics of ecodesign before concentrating on describing practical measures, where particular regulatory arrangements or design solutions have been shown to be effective.

The six axioms they set out are:

- Embrace and manage complexity.

- Make population and economic growth sustainable.

- Adopt interdisciplinary practice.

- Always require public involvement.

- Respect natural and built environments.

- Draw upon many design methods.

It’s hard to argue with these as intelligent, progressive and realistic propositions, except one: the idea that population and economic growth can be sustainable. It’s the language of the day, but conceptually flawed. On a finite planet, growth cannot be ‘sustained’ without its corollary of degradation and decline. I found this Axiom (#2) curiously at odds with the authors’ own trenchant observations about the sustainability of cities around the world; they state that “no city can be said to be even moderately sustainable,” a statement I find refreshing when the rhetoric of various international city rankings seems to claim otherwise.

Barnett and Beasley say that the suburbs are where the great innovations of the 21st century will have to be made and, in a sense, it’s hard to disagree. But as a universal guide to the ecodesign of cities and suburbs, the book suffers from being focussed on the North American experience in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Although many would argue that the rise of fossil-fueled sprawl is the quintessential urban (horror) story of our time and deserves to be positioned at the centre of any discussion on designing cities and suburbs, it is still not the primary lived experience for most of the world’s urban populations. A Tokyo ‘suburb’ bears little relationship to the suburbs of Phoenix, and neither of them have a lot in common with the favelas of Brazil.

The authors, and perhaps especially Beasley, who was co-chief planner for the City of Vancouver, are men with considerable experience in the art of convincing civic leaders and planners to make changes in the way they do things so that greater things may be achieved. The tremendous success of the reshaping of Vancouver under Beasley’s influence is testament to that. The writing in this book is consistently clear and to the point. In describing the gradual roll-back of automobile infrastructure in Portland, Oregon, for instance, there are deft turns of phrase as we learn that talk about demolition of more highway viaducts is not “an attack on the car culture,” but is simply removing “excess dedications of land for auto movement.” This is a kind of hypnosis—this is how the planner, the mayor and the highway engineer learn to embrace change and understand that efficiency of movement in an urban environment might be improved by not attacking cars, but by getting rid of roads!

Planners are faced with the challenge of making the transition from the mechanistic framework of 20th century modernism to the profound concern with living systems that our damaged planet and struggling cities demand. The concern is real but, as it is with most of the rest of us, the minds charged with making the changes now needed were trained in the old ways: they lived with the chimera of progress defined by technological advancement, rather than with ecological health.

The book sets out to be something of an omnibus, or at least a kind of primer for the emerging and vitally important practice of ecodesign, and it is comprehensive in its scope. However, it would have benefited from a set of references or a select bibliography that would have enabled readers to follow up on aspects of ecodesign that captured their interests.

The examples are generally well chosen. We learn that Seoul’s Cheonggyechon is “a good example of what we are calling good design, uniting principles of good urban design with restoration of the natural landscape…” Not surprisingly, New York’s High Line Park is included whilst the Promenade Plantée in Paris is granted its due as the “world prototype for adaptive reuse of…nineteenth century rail infrastructure.”

Nearly every page of this book has a one-liner or quotable passage that sums up critical ideas or information pertinent to making cities work through better design:

“We need to recognise that housing for everyone is a benefit for everyone.” (p.125)

“The bottom line for shaping cities is that neighbourhoods matter” (p.128)

“Walking is fundamental to our overall experience of a desirable city.” (p.181)

The challenge in implementing ecodesign is to transform ‘isolated successes into general practice.’ (p.209)

“Correcting obsolescence in the current regulatory regime is essential to the achievement of ecodesign.” (p.229)

“Regulations should not just avoid the worst consequences; they should strongly engender the best results.” (p.229)

Climate change and blind spots

The chapter on Adapting to Climate Change and Limiting Global Warming is strong on concern for sea level rise which, given the extent of the world’s cities that are under immediate threat, is understandable. The experience of cities dealing with rising sea levels and storm surges is instructive. Various examples of responses to climate change are noted in this book, from raising the building datum of the Marco Polo Terraces in Hamburg, Germany, to over 8 metres above sea level, to the barrages in London and Singapore and the efforts being made to create sea defences for New York City. Apart from sea level rise, climate change affects food production and ecosystem stability. Ideally, cities should burn no fossil fuels whilst providing excellent accommodation for their citizens. The examples of solar housing in Freiburg, the sustainable new district in Stockholm; Masdar, in the UAE; and Vancouver’s False Creek, all illustrate practical solutions to this kind of aspiration.

Many Australians, including myself, are concerned about climate change and sea level rise and, increasingly, the frequency and severity of bushfires. There has recently been a particularly severe and unexpected fire in West Australia, just outside Perth, in which almost the entire small town of Yarloop was destroyed by fire. Remarkably, only two residents died. The first reaction of residents afterwards was that the town should be rebuilt in the same place or close by. An excellent point made by Barnett and Beasley is that “Over time, adapting to increasing forest fire danger is comparable to adapting to sea level rise, but at some point the cost of maintaining houses in some locations will become untenable. Some areas will need to be rezoned as too dangerous for permanent habitation.” Denial runs deep in human culture—or is that resilience?

The authors identify three blind spots in the North American planning system:

- Land treated as a commodity rather than a living, complex, integrated ecosystem.

- Uses and densities separated—“We now know clearly that urban success is about mixing uses and densities in an almost endless variety of ways.”

- Zoning systems based on arbitrary categories rather than functional elements, “perpetuating social distinctions from the 1920s.”

Sprawl is hard-wired once built, but it is embedded in regulatory ‘software’ first. Getting rid of regulation that hampers desirable development (in the terms of this book) is not ‘free-market’ deregulation, but sensible pruning of redundant excrescence resulting from planning systems that were born in the early throes of modernism and were too brittle to evolve.

China has its own variants of the kind of prescriptive regulations that have done so much to promote sprawl and damage livability in North America and the anglo-centric ‘New Worlds.’ It would behoove Chinese planners to absorb the lessons of this book—one notes that Beasley has been an advisor to Tianjin in China. There are now many planners and urbanists in China who understand that the business-as-usual of industrial-consumer-capitalism is far from providing best practice outcomes for business, citizens or the environment.

Consumers, or citizens?

Part of the problem of tailoring one’s language to fit the dominant paradigm is that it then reinforces that paradigm. The authors presumably use the word ‘consumer’ because it fits the dominant paradigm of modern discourse, which seems to uncritically define everyone as a ‘consumer,’ but this paradigm is, in many ways, what this book is setting out to challenge.

‘Citizen’ comes from the very root of ‘city’ and denizen, marking someone as living in a place. A consumer is just an end-user, a purchaser of goods. Consumers are inherently powerless, whereas citizens have rights and obligations and roles in the society of which they are part, and which do not depend on whether they buy anything. The homeless and dispossessed are as much citizens as any property owner and, in what’s left of modern liberal democracy, they have a right to vote and engage in the political process that is not defined by how much they own or spend. I take issue when the authors argue that following ecodesign principles requires substantial and sustained involvement of people in the design and management of regulations and so forth, but then proceed to argue that the political process is for citizens, whereas the design process is for consumers. Why the separation? Using ‘consumers’ as a general term for people who live in cities is the same kind of newspeak that calls a corporation a person.

It is dangerous to diminish the concept of citizenship in any way, and particularly dangerous to define people as consumers. If there is a blind spot in the planning system because it views land as a commodity, rather than as a living system, then that can only be confounded by viewing citizens as consumers. The distinctions here are critical. Consumers are defined in relation to commodities, in a variant of the capitalist system that is recent in human history and has reduced the richness of life to little more than a kind of marketplace.

The authors’ agenda is fundamentally radical, but they are writing for the mainstream. Writing about the challenges of mixed-use development, for example, they note that “Looking out at a balcony filled with bicycles, barbeque equipment and storage boxes can upset office workers because they say it diminishes the business feel that they prefer.” Solutions to this aesthetic conundrum, apparently, include things like opaque railings. I’d like to have seen an argument for some cultural change, especially as Vancouver does provide an excellent example of a city that has made an enormous and successful change to both its planning culture and regulatory environment to favour mixed-use, density, social diversity and family-friendly environments in the city’s downtown. Importantly, it also stresses the role of landscaping and the use of trees, vegetation and convivial outdoor spaces to make the city work the way cities should.

The observations in this book are all cogent and to the point. For example, regulations for Compact Mixed-Use Urban Centres “should allow a richly compatible combination of activities, directed toward the totality of the place that is being created rather than just the integrity of any one use.” But whereas there is attention to detail for the ‘hard’ infrastructure associated with such things as the management of stormwater—down to the level of illustrating a rain barrel—there is no equivalent attention paid to any detailed means by which natural systems might be nurtured and integrated with human demands. Clearly, nature is to be respected and accommodated in the ecodesign ‘vision,’ but I was left with the sense of it being tolerated rather than embraced. There are no examples of wildflower meadows or wildlife corridors in the book, for instance, that might have provided solid examples of natural systems solutions.

The book is, overall, supportive of the basic tenets of New Urbanism and the authors acknowledge that New Urbanism projects in North America are important exemplars. But they point out that New Urbanism developments have all been ‘one-off,’ special case, up-market, single developer creations that are hermetically sealed from the regulatory framework (and often the transit system) of the cities that have allowed their development.

Design with nature?

In the index of this quite comprehensive volume, you won’t find the word ‘resilience.’ Most TNOC readers would probably consider ‘urban ecology’ and ‘wildlife’ to be important considerations in any discussion of ecological futures for cities, but none of these features in the index. Neither will you find ‘citizens,’ ‘natural systems’ or ‘ecosystem.’ It’s not that these topics aren’t covered (e.g., Anne Whiston Spirn and natural systems are mentioned, and their importance recognised), but they are key words that I expect to find when interrogating a book about ecodesign, and I was surprised that they weren’t there. ‘Animals’ don’t feature in the index either. The role of animals in the city, whether wild or companion, is neglected, or, at least, not dealt with specifically.

One shouldn’t expect any single book to be encyclopedic, but when the topic is inherently about systemic thinking, design and the integration of cities with nature, it raises certain expectations. Whereas there is strong material and many concrete examples throughout the book, the role of ecology is not presented with the same degree of specificity. This book is very much about the human part of the urban system. To provide the missing balance, I’d recommend reading it in conjunction with Michael Hough’s classic Cities and Natural Process (he’s not in the index either).

A thoroughly sound discussion of the public realm is a real strength of this book—sufficient to grant its entry into the library of any urbanist—but its value as a key text for ecodesign would have been enhanced by an equivalent emphasis on the realm of all the non-human species on which, ultimately, the public realm depends for its existence. The authors acknowledge these, noting that the public realm has been “exploited without reference to natural systems, and their potential to facilitate a connected web of ecosystems has been ignored.”

As the authors put it, “Ian McHarg’s well-known injunction to design with, not against, nature will have to become a basic principle of development regulation. It is certainly a fundamental tenet of ecodesign.” When McHarg made the case that architects, planners and engineers should work with natural systems and not try to construct against them in his 1969 book, Design With Nature, he was developing ideas going back through the lineage of Mumford, and Geddes, and the Tao. But the point is well made by Barnett and Beasley that McHarg’s experience of the evolution of natural systems was “so slow that for practical purposes nature could be considered to have a stable structure.” Now, under the influence of global warming, nature is changing rapidly and, as a consequence, “the issues he identified (are) even more urgent.”

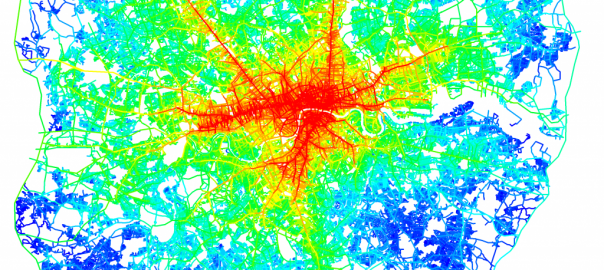

Nearly half a century after Ian McHarg put forward the basic concept of what we now know as GIS, using tracing paper overlays and hand drafting, we have computer systems that enable sophisticated mapping of this kind to be done swiftly and accurately, and to be readily distributed in a way far beyond the reach of pre-computer copying techniques. This makes Barnett and Beasley’s call for the use of GIS maps as the legal basis of development decision-making, so that ecosystems can be properly integrated into planning, an entirely reasonable proposition.

It is because the authors clearly speak from experience that one can read and believe a statement like, “The agenda of a discretionary regulatory system and transactional development management process can embrace anything relevant in the modern city; nothing is too complex to be incorporated.” But nature doesn’t engage in negotiation, it provides the fundamental environment within which human transactions take place, so it’s difficult to accept that this process “…can broker neighbourhood conflicts and reconcile settlement and ecology in fine variations that represent the reality of the natural environment and human expectations.” (p.228)

Dancing with nature

The prospective readership for this book would obviously include students of the subject, but it should find a wider readership. Many will be familiar with the basics of ‘ecodesign,’ but may not have access to such a succinct description of what has been achieved in practical terms to introduce ecocdesign initiatives to cities. As such, the book is a valuable reference for policy planners and elected representatives. Active citizens stand to be informed and empowered by this book; I would imagine that almost all TNOC readers would find it of interest.

Yes, I did want this book to make more of a song and dance about nature, but it is a very good book, packed with information and quotable material, and it left me pondering, yet again, the question of how we can transfer from the careful world of not saying the wrong things to a world in which we can be forthright about the absolute needs of nature as part of how we make cities.

Paul Downton

Adelaide

Add a Comment

Join our conversation