Mindy Fulllilove, Columbia University psychiatrist and author, likens pedestrian pathways and urban trails to arteries in the circulatory system of a city: essential conditions for creating a healthy city. There is much to be said for neighborhoods that are physically connected, and where it is possible to move across a city easily (and joyfully). A coherent sense of one’s entire city is one benefit, as well as an ability to experience the different ecological zones and habitats there. A well-developed urban trail system delivers substantial health benefits, helps to entice and tempt residents outside, and is recognized as a key positive attribute of quality of life. And it can provide important ecological connections and movement corridors for the many other species with which we share urban spaces.

Many of the cities in our Biophilic Cities Network offer some inspirational examples of the importance and power of investing in networks of urban pathways and trails. For instance, Singapore continues to expand its Park Connectors system, tying together major parks and nature areas, and making it remarkably easy for residents and visitors to experience nature and to spend time walking outside. Some stretches of this network offer especially dramatic perspectives on both nature and the buildings and other built elements that sit within this “city in a garden.” My favorite stretch is the Southern Ridges, where much of the trail is elevated, taking one directly through the tree canopy. The trail in several points floats above and across major roads below, and bypasses ground level car traffic through bridges including the visually striking (and quite biophilic) Henderson Waves. This bridge serves as new vertical public space, as visitors and residents stop to rest or picnic at the top. One walking on this stretch of the Park Connectors is likely to experience a lot of nature, from birds and abundant butterflies to more unexpected nature, such as the Monitor Lizard that I encountered one day on this trail.

In New York City, Mindy Fullilove has been instrumental in creating the so-called Giraffe Path—a 6-mile long pathway connecting seven different parks in northern Manhattan. Hike the Heights is a yearly event that Fullilove and others have helped create, which “invites New Yorkers to explore and celebrate the area’s natural treasures by combining physical activity, art and fun!” One aspect of this event is the “Parade of Giraffes,” where kids create giraffes of all shapes and sizes, which are then displayed in the parks along the walking route.

What are some of the desirable qualities of an urban trail system? It ought to provide opportunities for short meanders, as well as longer treks and, ideally, ought to connect important sites and destinations. Urban trails offer the chance for brief respites, to see and experience nature close to where we live and work, and to provide unique and different ways to see and experience the city. And a trail system ought to accommodate a variety of different ways of moving through these spaces (e.g., hiking, biking, cross-country skiing—popular in northern latitude cities). As an example of the diversity possible in urban trail systems, consider Anchorage, where there are more than 120 miles of paved, multi-use trails, but also 130 miles of “plowed winter walkways,” extensive ski trails and even 36 miles of dog mushing trails!

Once an urban trail network exists, there is still work to be done in stimulating its use, and in getting people outside and walking through the city. Events and celebrations are important, as the Hike the Heights event suggests. Urban trail maps are also helpful (and there is a Hike the Heights Map). Increasingly, iPhone apps can direct, guide and inform urbanites about green spaces, parks and sites to visit (e.g.,TrailLink, developed by the Rails to Trails Conservancy), but they can also be tools for generating spontaneous group walks and hikes, bringing urban residents together for the purpose of walking and hiking (there are a number of apps, such as Gociety and Snowflake, aimed at helping to coordinate social activities and events, such as skiing and hiking).

Urban trails ideally provide access to spaces and places in and around cities that may be largely invisible or difficult to see or access otherwise. The more than five miles of trails allowing access to Mt. Sutro, a prominent green landmark in San Francisco, is an example. The Mt. Sutro Stewards, a volunteer organization, has taken on building and maintaining these trails, and gradually restoring native California plants, in partnership with UC San Francisco. Craig Dawson, co-founder of Mt. Sutro Stewards, has noted the “mystery and attraction” of the mountain, which he grew up exploring. There are typically many such hidden ecological and historical gems that are opened up through such trail building as this. This trail will eventually connect to the longer Bay Area Ridge Trail, a 350-mile trail that circles the San Francisco Bay. One neighborhood space of exploration and mystery can then lead to larger (and longer) urban nature trekking.

Signage and wayfinding are other important elements, and maintenance and safety are critical as well. Anchorage has one of the most extensive systems of urban trails anywhere, and an army of citizen-volunteers—through a program called Trail Watch—patrol and monitor the trails, equipped with their cell phones and identifiable by their visible arm bands. Biophilic Cities Network partner city Vitoria-Gasteiz, capital of the Basque Country in Spain, has an extensive network of trails, with the ability to reach fairly distant municipally-owned forests, and has installed unique trail signs that graphically depict the distance to each destination, allowing hikers to decide where they want to walk and explore given the time and effort they have to expend.

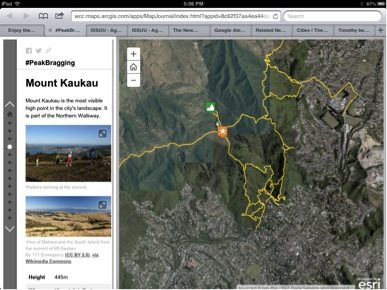

Getting urbanites out and hiking the city and its environs remains a challenge, and some cities are using some clever strategies. Wellington, New Zealand, another of our partner cities in the Biophilic Cities Project, has been running a campaign to encourage residents to hike its extensive network of trails. Throughout its summer 2016, residents are being encouraged to hike to the top of one of twelve peaks in the city and to post a creative photo with the hashtag #PeakBragging. As the City’s parks page suggests, it’s a friendly chance to give your friends some “gloativation to get outside and be active.” The photos posted are exuberant and funny, and do provide a glimpse of the magical views awaiting residents. The city awards prizes for the best photos and makes it easy to participate by providing a series of interactive maps of the spaces and trails around these peaks. One of these interactive maps, for Mount Kaukau park, is provided below.

Thinking about the many potential ways that humans move across a city further helps us to think about the needs of the many other species we share city spaces with, and how they must move around as well—we need to be equally concerned with their movement and safety. A notion of the city as habitat understands that there are many biological routes and pathways and trails followed by non-humans (from fish and bird migration routes to micro-movements of insects, amphibians and small mammals crossing streets and city spaces). Singapore has been a leader in this regard. They have an initiative called “Nature Ways,” aimed at creating biological connections and corridors between biodiversity-rich sites in the city. Singapore NParks is responsible for planting new trees and vegetation to ensure these connections, and there are now some 60 kilometers of Nature Ways there.

Other cities, from Brisbane to Edmonton, have invested in wildlife bridges and passageways to ensure biological connectivity for humans’ co-inhabitants in the city. Edmonton has adopted an engineering manual that enshrines wildlife passages (of various sizes and types) as a regular design consideration in future infrastructure projects. The city has built 27 wildlife passages to date.

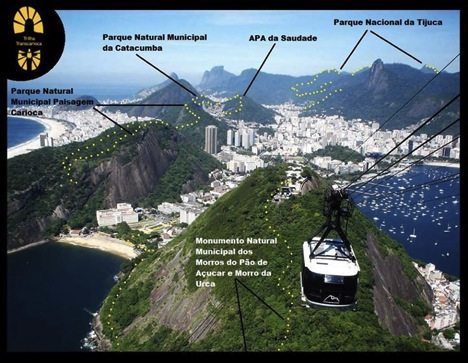

Trails have the ability to physically connect different and important elements of nature in a city, to provide biological connections and linkages and to create important spaces for bringing people together. One of the most ambitious urban trail projects is the Trilha TransCarioca, a trails network under development in Rio de Janeiro. As the maps below indicate, it would traverse that city, allowing a resident to travel from shore to mountaintop, linking major parks and ecosystems, including the city’s iconic Tijuca National Park. I spoke recently with Pedro Menezes, who came up with the idea for the trail some twenty years ago and is finally seeing it come to fruition. The vision is audacious indeed—eventually, it would extend 250 kilometers in length’ already, some 120 kilometers have been built and are open to the public. Providing movement corridors for species, such as toucans, is one of Trilha TransCarioca’s primary goals. “We also want the trail to put the Rio population closer to its nature,” Menezes tells me, “so they can cherish more, appreciate more the value of it, both in terms of recreation, but also in terms of ecosystem services…” So far, volunteers have largely driven the effort, with more than 2,000 volunteers actively involved. “The enthusiasm is great,” Menezes says, telling me about a recent volunteer training event where they expected 250 to sign up, but instead had more than 1,000 people. Such an urban trail is clearly a matter of pride for many, and will certainly become a highly valued aspect of the Rio urban experience.

Like the Rio trail, many of our best urban trail networks occur along water, offering impressive vistas of nature and responding to our innate tendency to find places of “prospect and refuge.” Coastal cities from Oslo to San Francisco to Sydney offer examples of how walking, jogging and hiking can place one in close proximity to the marine world. The Boston HarborWalk and the new San Francisco Blue Greenway are positive examples of this trend.

Few coastal trails are as impressive in length and diversity of experience as the Waterfront Trail, which now extends some 1,600 kilometers along the edges of Lake Ontario and Lake Erie and beyond (and is managed by the nonprofit Waterfront Regeneration Trust). Running through downtown Toronto, the trail connects some 80 communities and many parks, including the Rouge National Urban Park, Canada’s first urban national park. The trail has the special value of connecting urbanites to the larger Great Lakes landscape, serving as an important boon for tourism and economic development (a yearly multi-day bike ride, called the Great Waterfront Trail Adventure, has become a signature event).

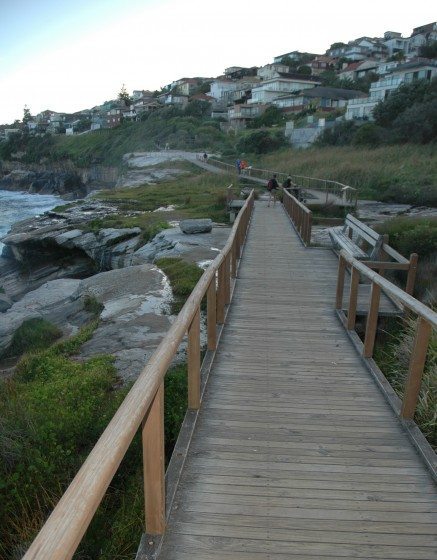

Years ago, we lived for a time in Sydney, Australia, and were especially impressed by the availability of walking and hiking along the steep edges of that coastline, connecting beaches and providing dramatic views of the ocean and shoreline. Relatively simple wooden structures hugged the coastal cliffs, with ocean pools and other stopping spots along the way. From our home in Coogee Beach, we often traveled along the Coastal Walk south, sometimes north. It was a remarkable aspect of daily life, at once recreational and therapeutic, a multi-sensory adventure that brought us in daily contact with the immensity and wildness of the South Pacific Ocean.

These kinds of urban trails and pathways, which bring us in close proximity to water, represent an important element of blue urbanism. But many cities are going even further, now commonly thinking about the potential of blue trails that exist on or in the water—along riverways and waterways that could be traversed by canoe, kayak or water taxi. In our partner city of Milwaukee, there is an Urban Water Trail and there is an elaborate network of water trails in New York City, connecting all five boroughs there. Wellington has even established a snorkel trail, a part of the Taputeranga Marine Reserve. Increasingly, our notion of an urban trail must include and extend into the marine and aquatic realms (not just beside them).

How cities might equip citizens to make the most of these water trails is an interesting question, and I am intrigued by recent experiments with some form of canoe-share or kayak-share, similar to (or in combination with) bike-share systems now common in cities around the world. Purchasing a canoe or a kayak is a significant monetary obstacle, and creatively making such bluescape vehicles easily usable, for short periods of time, would be helpful indeed.

To return to Fullilove’s metaphor, biophilic cities require a healthy circulatory system of trails and pathways to provide social and biological connections. But they also allow us explore, to discover, to experience (close to where we live and work) moments of exhilaration and awe, and to provide vantage points and perspectives that allow us to see the whole of a place, and to understand where we sit within this urban ecological tableau.

Tim Beatley

Charlottesville

Tim. Thank you for report on “The Value of Urban Trails”. Check out my website, NatureTrailMap.net.

NatureTrailMap.net makes it possible to use 200 miles of urban nature trails in San Antonio, Texas as a way to experience nature, and, as a transportation system.

With NatureTrailMap.net you step out of a nature trail and then touch a bus-stop icon for the next bus.

Tim, your words are like a fun magical trail. You don’t quite know what to expect around the corner! Providing the trail that is close to home and yet dismisses all auto mass, noise, pollution and infrastructure is as relaxing as a bath with a favorite beverage!

The value of such path systems are a mark of a town! So, one can leave the city of heavy action and calm right down to a joyful journey which rewards with peace and tranquility. I would encourage anybody to seek places that help them restore/relax and gain a appreciation for their urban paths!