A review of Projective Ecologies, edited by Chris Reed and Nina-Marie Lister. 2014. ISBN: 1940291127. ACTAR, Harvard Graduate School of Design. 314 pages. Buy the book.

Several months ago, I reviewed Landscape Imagination, a collection of essays by James Corner, a professor at University of Pennsylvania and the landscape architect who designed New York City’s celebrated High Line. Composed over twenty years, his essays examine the many factors hindering the advancement of the cultural medium of landscape. One factor Corner repeatedly addresses is the hoary old dichotomy between nature and culture still pervasive in landscape architecture—the belief in a pristine nature separate from humans.

While the essays in both collections are exquisitely written, I am hard pressed to imagine contemporary built landscapes that actually represent the challenging ideas conveyed in either book. This dichotomy between landscape as idea—in academic writing and imaging—and the actual production of landscapes—in the common client/contract model of practice—is not new. Nor is it unique to the discipline. But like nature versus culture, the idea versus practice dichotomy leaves landscape architecture ill equipped to work effectively in a world of quickly hybridizing landscapes.

Projective Ecologies aims to recover a critical sense of ecology for the design professions because they operate at the intersection of nature and culture—particularly landscape architecture, since its medium holds unique environmental, social, and existential opportunities and responsibilities. Emerging from a multi-year research initiative at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, Reed and Lister drew on Foucault’s The Archaeology of Knowledge to present three “parallel genealogies,” or intellectual traditions, dealing with the concept of ecology: natural sciences, the humanities, and design.

Projective Ecologies aims to recover a critical sense of ecology for the design professions because they operate at the intersection of nature and culture—particularly landscape architecture, since its medium holds unique environmental, social, and existential opportunities and responsibilities. Emerging from a multi-year research initiative at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, Reed and Lister drew on Foucault’s The Archaeology of Knowledge to present three “parallel genealogies,” or intellectual traditions, dealing with the concept of ecology: natural sciences, the humanities, and design.

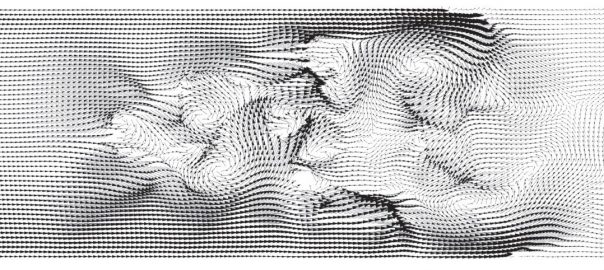

Reed and Lister abandon any hope of editing a chronologically linear exploration of ecology across the disciplines. Instead, they take a cue from it, and tend a wild garden of vines and sprawling, root-like ideas with no center and no linear narrative. While it was once believed that ecosystems were linear, gradually and steadily reaching stability until disturbed by an external force, it is now understood that change is built into them. Biologist Robert E. Cook eloquently explains this paradigm shift in his essay “Do Landscapes Learn? Ecology’s “New Paradigm” and Design in Landscape Architecture” (1999). For Cook, ecosystems depend on change for growth and renewal.

All of the essays are at their best when they investigate the consequences of design and planning operating from the old paradigm in ecology. Jane Wolff demonstrates how decades of decisions and actions from within the old paradigm made Hurricane Katrina such an unprecedented disaster for New Orleans. The complex hybrid ecological systems that have emerged in New Orleans are making rehabilitation efforts nearly impossible. David Fletcher discusses how Los Angeles River revitalization efforts are led by goals to fix the river rather than understand what it has become. This desire to return the river to a “natural” state threatens its urban ecologies, which have adapted to perform significant ecological functions independent of human agency.

Erle C. Ellis, a professor of anthropogenic landscape ecology at the University of Maryland, further explains why these dichotomies are so troublesome in his contribution “Taxonomy of the Human Biosphere.” Ellis defines our new geological epoch, the Anthropocene, as “the completion and permanence of human influence on the terrestrial biosphere.” He argues that the Anthropocene began roughly 10,000 years ago, when humans first started planting crops. The epoch really got underway with the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. Anything that was not altered before is now undergoing rapid changes caused by human-induced climate change. The future of all species, including our own, sits entirely in our hands. Ellis makes a case for understanding and managing our anthropogenic biosphere by moving beyond the mythology of humans as destroyers of a pristine and fragile nature, a theme that is central to the nature versus culture dichotomy. Since this cultural perception of nature does not actually exist in the reality of a biosphere that is now a hybrid of nature and culture, it will not empower us to create nurturing landscapes in the new epoch. Likewise, if we cannot get our most innovative and challenging ideas out of books and into real landscapes, we will squander an opportunity to determine a proud future.

The essays offer three important perspectives of ecology to better understand ecology as a model of the world and the agency exercised by design and planning in shaping that world. The first perspective from Projective Ecologies is that ecology has transcended its origins as a natural science. The expansion is trans-disciplinary, cutting across the natural and social sciences, history and the humanities, design and the arts. It also pertains to the pervasive co-opting of ecology as an overused metaphor for any general idea about environment or as a poorly understood stand-in for the idea of dense networks of connectivity (see any recent issue of Forbes or Fast Company in which entrepreneurs explain the “ecology” of their multi-million dollar “ecosystem”). In Christopher Hight’s essay “Designing Ecologies,” he declares ecology among the most important epistemological frameworks for the environmental narrative of our times. But because of ecology’s expansion—and, consequentially, its descent into simplistic truisms that everything is interlinked and interacting—it loses its meaning as a specific idea. Reed and Lister say, “few designers have ventured beyond the metaphors and mechanics of these two-decade-old models to design effectively for adaptation to change, or to incorporate learned feedback into the designs, or to work in trans-disciplinary modes of practice that open new apertures for the exploration of new systems, synergies, and wholly collaborative work.”

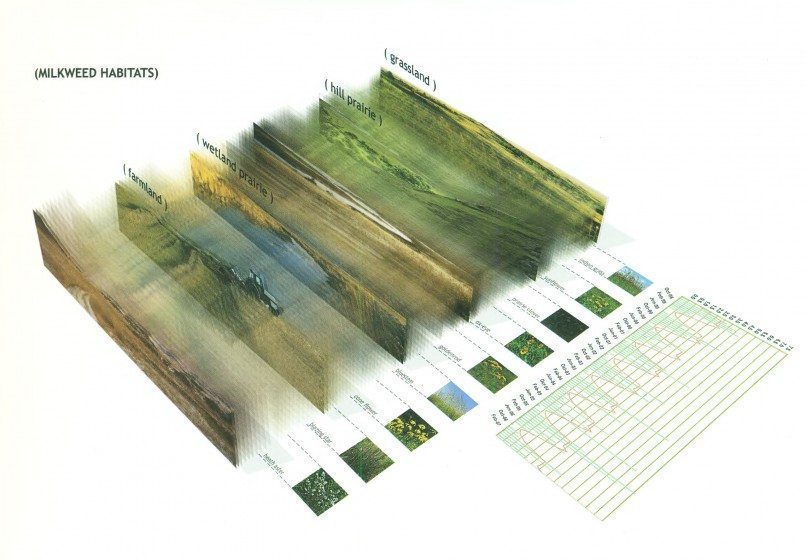

The second perspective from Projective Ecologies (as implied by the title) is that ecology is actually a plural concept, spanning a broad spectrum of fields. Some of the specialized areas of ecologically oriented research that have emerged, include: landscape ecology, human ecology, urban ecology, applied ecology, evolutionary ecology, restoration ecology, deep ecology, the ecology of place, and unified theory of ecology. These appropriations are responses to the importance of ecology as model, metaphor, and medium for the interrelationships between plants, animals, and the physical, biological, cultural, and experiential world. In a hybrid world of nature and culture, singularities—such as ecology existing outside the city, and urban as external to ecology—no longer exist.

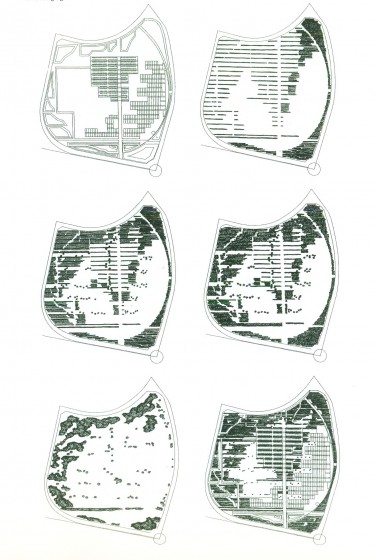

The third main perspective in Projective Ecologies is that ecology holds projective potential for the design disciplines. Reed and Lister explain that, “as ecologists are limited by their conceptual models of ecosystems rarely able to be tested on ecosystems themselves, the term projective thus embraces the creative and speculative ambitions of representation.” Reed and Lister model a speculative and creative approach with the very structure of their book, layering essays, drawings, and other graphics in an effort to bring new connections and new ideas to light. Chris Hight explains a projective ecological program of design as less about organizing matter or even catalyzing processes, as much as it is about researching the critical junctions and “pressure points” of systems. Projective Ecologies proposes a synthetic understanding of ecology as a medium of thought, exchange, and representation for design.

While Projective Ecologies raises many questions about the future of ecology and urbanism, it left me asking one critical question: “What is next in the lineage of the project?” We can surely anticipate similar collections of essays and drawings from ecological thinkers. But how does ecology as a medium of thought, exchange, and representation translate to the messy realities of our cities? How does it translate to practice more broadly? How do mid-career practitioners like myself “catch up,” so to speak, with advancements in the ecological paradigm shift since we were in landscape architecture school? How do we become familiar with the realities of a hybridized world shaped by cultural intention and natural process?

Jane Wolff asks a question in her essay, “Cultural Landscapes and Dynamic Ecologies: Lessons from New Orleans,” that is applicable across hybrid landscapes: “What can be done to address the tension between what we know and what we do? With enough public investment, the technical dilemmas posed by New Orleans and southern Louisiana could be addressed successfully. The most significant obstacles to progress are cultural. The need for public literacy about New Orleans’s hybrid ecology suggests a new role for landscape and urban designers, who have the skills to mobilize, represent, and synthesize information about current conditions and more resilient alternatives.”

Perhaps attaining more widespread ecological literacy should be the first goal in breaking down the “nature versus culture” and “ideas versus practice” dichotomies plaguing landscape architecture. As practitioners, taking responsibility for our own knowledge will allow us to better use our skills and creatively mobilize, represent, and synthesize information for the public. These goals may not be practical within the dominant model of practice where methods are monetized, outputs are commoditized, and the march of ecological time is suspended to create landscapes with instant appeal. But the world depends on us to learn from ecology and create hybrid forms of ideas and practice that enable us to better understand the ecosystems and human populations we impact through the landscapes we shape. Offering up the insight that we may not be making the most of a diverse and complex concept of ecology, is, perhaps, the greatest success of Projective Ecologies.

Anne Trumble

Los Angeles

Great review thanks Anne!