The other day, I took my two children to the park. We clambered over rocks and logs, slid down slides, and rolled down a large grassy hill.

The park was the Royal Park Nature Playground in Melbourne, and our visit there was a reward to the three of us for having sat through a long, boring meeting. We arrived at the park tired and grouchy, but within seconds of our arrival, all we could see were golden opportunities for fun.

The tension in our bodies had no chance against the joy of being out in the open, indulging in the overwhelming desires to run and move and sing and discover. It was a powerful demonstration of how important it is to have access to spaces that really MOVE you—physically and emotionally—as part of everyday life.

Because understanding the ecosystem services of green spaces is part of my job, it can be easy for the cultural services to become simply items on a list. My experience at the park was a timely reminder that I also need to be diligent about enjoying those benefits for myself. It was also an affirmation that the career I am carving out for myself actually can change our relationship with and understanding of cities. Standing at the top of that hill, I was humbled to suddenly realise: “I helped build this”. Not in any tangible, hands on, or direct way—but indirectly, through my participation in the burgeoning field of urban ecology. The research into the ecology in and of cities I have contributed to is now manifesting as beautiful, multipurpose, engaging parks such as the one I was standing in. That wonderful revelation left me feeling inspired to continue working towards creating opportunities for all city dwellers to have access to places that can have a meaningful and positive impact on their lives.

The pull and push of highly valued green spaces

I am a glass half full person, but I am also a realist. In the days that followed my visit to the park, I started to think about what goes into making a park like that. If I rolled back the turf on that fabulous big hill, what would l find? Where do those beautiful boulders come from, and what will happen if we keep gathering those rocks to use in other parks? Are there enough weathered logs to feed our desire for naturalistic playgrounds? And how can we make sure that these parks are distributed equitably now, as well as into the future? These are some critical questions that I would like to explore in the remainder of this essay.

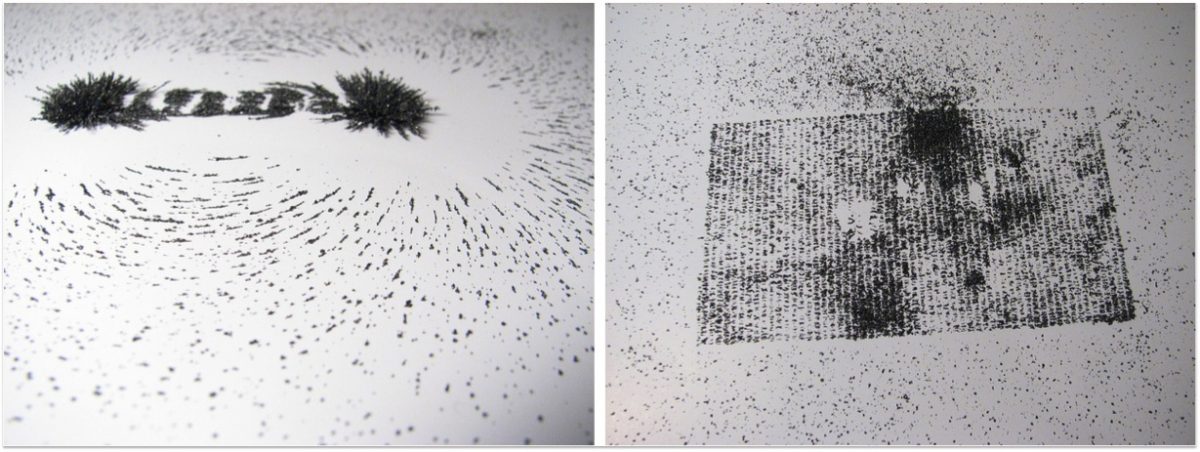

A useful analogy to help with this discussion is the relationships between magnets and metal filings. The forces of attraction and repulsion combine to reveal the shape of the magnetic fields by creating clearly defined areas with and without filings. Some magnets have quite strong fields and produce very clear patterns, whereas others are much weaker and barely make an imprint.

If we think about parks as being magnets in an urban area, the filings are a way of visualising the impact they have on the economic, environmental, and social dimensions of the urban landscape. Outstanding and engaging parks, such as the one I described, have stronger and farther-reaching magnetic fields compared to the smaller parks with fewer resources, which have only a limited effect on a smaller number of filings. However, these strongly magnetic parks also create more obviously binary landscapes, and accumulate a much larger volume of filings.

Environmental consequences

If the current status quo for parks is to deliver open areas of turf with a tree canopy, then increasing the number of large or naturalistic parks, with undulating land forms and a diversity of physical features (such as rocks), will require a far greater quantity of physical materials during the construction phase. Where will these materials be gathered from, and what is the ecological impact that results from their relocation? Are the ecological benefits of improved habitat diversity in urban landscapes dwarfed by the associated depletion of habitat elements in more “natural” landscapes? There is no single answer to this question, as it will depend on the contractors, their suppliers, the local context, and a multitude of other factors. However, the first step towards fixing a problem is recognising it exists. By questioning and tracking the net impact of a park, we can develop a better understanding of whether the construction of these spaces is truly justified by their impact on the ecology of our planet.

Social justice and equity

Magnets exert two key forces: attraction and repulsion. The simplest demonstration of these forces can be found in toy train sets, where the carriages connect through magnets. The carriages stick together through the force of attraction. However, if you take a carriage off the end of the train and try to reconnect it using the wrong end, the force of repulsion pushes the carriages away from each other, and the train no longer pulls the carriage.

Parks with strong magnetism can potentially exert the same forces of attraction and repulsion for people. A great park will draw people to it, even from larger distances. However, such parks also hold the potential to push other groups of people away. For example, the development of a “great” park may increase surrounding land and rental prices, thereby making it unaffordable to many long-term residents of the neighbourhood. In our efforts to provide better parks without creating a social justice divide, we need to identify additional mechanisms to ensure that when strongly magnetic parks are built for disadvantaged communities, the same communities will continue to be able to enjoy them into the future.

Economic forces

Too often, the things that start out as a consideration of the triple bottom line (social, environmental, and economic forces) eventually get made on the basis of the original, single bottom line: money. Parks with strong magnetism cost more to design and to build than a basic “trees and turf” park. There are also unanswered questions about how much new maintenance approaches will cost compared to the current mulch, mow, and spray approach that we currently appear to be comfortable with. If a new style of ecological parks is going to be more widely adopted, then we need to start integrating the requisite ecological maintenance into the design to minimize the ongoing costs of management. We also need to start recording the maintenance costs for the parks that are built in order to establish the business case for (or against?) a change in the type of parks we build in our cities. As the management costs increase, there may also be more incentives to engage local residents to assist in caring for the parks. This would have the added advantage of providing opportunities to strengthen social bonds within communities, and to connect more people with nature.

A deeper appreciation for parks can change their magnetism

If sustainability is about making more effective use of our existing resources, then there is a case to not only build great parks, but also to explore how we can “re-use and recycle” our current parks to raise their perceived value in the community. Is it possible to adjust the magnetic fields of a park in ways that maximise their magnetism for people and biodiversity, yet minimize the ecological and economic impacts? For example, can simple stewardship activities change the relationship that residents have with their local park? Can simple changes in park management deliver improved biodiversity outcomes, or extend the range of benefits that a park can deliver? How can the ecological or social benefits of parks be increased while the essential design is unchanged? Expanding our park networks in the most sustainable way may require us to see every park—regardless of their many and varied forms—as an asset to be nurtured, improved where possible, and more fully and universally appreciated. In our roles as professionals and citizens, exploring this dimension could be the greatest sustainability challenge of all.

If the magnetism of parks helps shape our cities, how can we use the arrangement of magnets and strengths of magnetic fields to maximum effect? Strongly magnetic parks have been used regularly to shape cities (think emerald necklaces and green spines, for example). Yet it is possible that all parks have the potential to act as magnets and contribute to shaping our cities. If this is the case, how can we use our full diversity of parks to “tune” cities and deliver positive results across the triple bottom line, now and into the future?

The focus of this essay was clearly on parks and how they contribute to efforts at creating sustainable cities. However, many of these same dilemmas and challenges apply equally to other components of our built environment, including buildings, roads, artificial night lighting, water sensitive urban design, and the plethora of other infrastructure present in cities. As I walk through my city’s streets, I now wonder about the magnetism of all of these things that I see, and think about the trails of iron filings that they have created. It affects my vision, but it also makes it even more apparent that truly sustainable cities are only possible where we minimize the detrimental environmental, economic, and social impacts, and then actually take the time to value and appreciate the benefits. This valuing process is the essential ingredient for moving an idealistic search for sustainability into a meaningful way of life.

Amy Hahs

Melbourne

It is my impression that far fewer children (and old people) are attracted to urban parks now that feeding ducks and other birds is forbidden. The next generation will be less empathetic towards nature. If white bread is not healthy why not provide bags of seeds that can be bought.