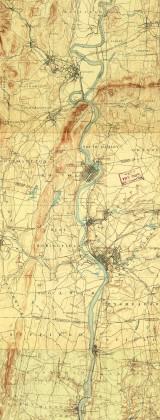

I left Springfield to study architecture in 1974, two years after passage of the Clean Water Act of 1972. The first watershed association in the U.S. was established the Connecticut River Watershed Council two years before my birth in 1956. I can measure my return to the Connecticut River Valley some four decades later against the socio-ecological changes in the water and land of the Connecticut Valley as the result of water management following the introduction of Environmental Protection Agency in 1970, but most importantly, the social urge to abandon the old industrial centers, and build a new city within the old tobacco and corn fields of the Connecticut Valley.

As William Cronon has demonstrated in his book Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists and the Ecology of New England,new social practices can completely alter an environment in a generation. Comparing 17th century explorers accounts of the first encounters with the Native American landscape of New England with the with descriptions of the colonial landscape at the end of the 18th century, Cronin situates historical change within socio-ecological processes tied to belief systems and economic practices. He concludes that the deep ecosystem knowledge that the Native American’s had was not recognized by the colonists bent on an attitude of “land improvement” rather than ecological stewardship.

Returning home, I felt a similar kind of urban knowledge was lost, as my parents’ “greatest generation” lost contact with the institutions, social alliances into which they were born.

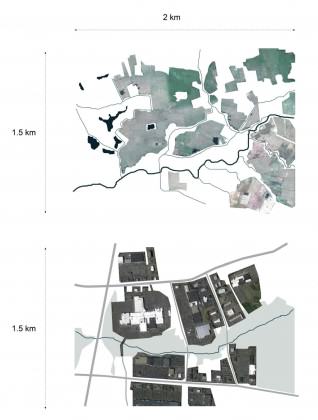

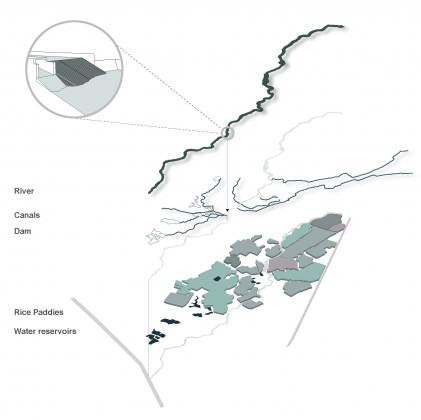

This year I began an urban design research project on recent urbanization in the Mae Ping River Valley city in Chiang Mai, Thailand. My research framework is to compare indigenous and scientific practices in water management in relation to urban resilience in the face of climate change as part of a sabbatical leave generously provided by The New School. I was drawn to Northern Thailand in order to understand the famous muang fai gravity-fed weir and canal based irrigation system for wet paddy rice farming that evolved over many centuries. My home in Chiang Mai affords me an intimate view of this system along the Mae Kuang River, a few hundred yards below a community-managed weir.

For a New Englander, this flexible, adaptable and resilient water management practice reminded me both of the wetland engineering qualities of the native North American beaver, and Native American socio-ecological knowledge described by Cronin. The muang fai remain remarkable examples of community based natural resource planning, design, management, adaptation, and resource sharing, even in the face of extreme pressures of urbanization and centralized government development policy.

This work, far afield, as has often been the case during the previous decade of my life, has been regularly interrupted as I try to return to the place of my birth and upbringing to care for my parents, aunts and uncles as the normal end cycles of human life take its toll on their generation. What started as an exploration of indigenous socio-ecological practices in Thailand has resulted in an inverted telescope looking at the American landscape from Southeast Asia, much as Benedict Anderson describes in The Spectre of Comparisons. Through this inverted telescope, I began to compare the muang fai system’s network of irrigation dams and canals to the Connecticut Valley’s legacy of beaver dams and industrial mills.

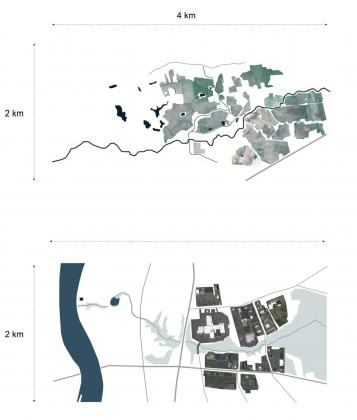

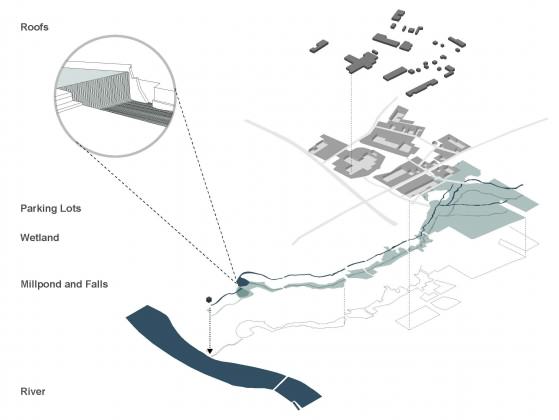

Around Springfield, alongside and replacing this concentration of early urbanization at water power sources exists a landscape of shopping malls, industrial parks and housing subdivisions, which since the 1970’s has been more and more carefully managed through the creation of point-source water pollution restrictions, wetland boundaries around non-point pollution sources. Since selling our family house in the city of Springfield, I have a close-up view of this new landscape. I now often stay on of the hotels clustered at exit 47E on Interstate 91, just over the state line from Springfield. Motel 6, Red Roof and Hampton Suites all have robust storm water management systems between their parking lots and the Freshwater Brook in Enfield, Connecticut, and the shopping malls at Enfield Square and Enfield Commons form a super-block with the fenced brook as its ecological “commons”.

While in Northern Thailand I am studying new patterns of urbanization in relationship to indigenous water management practices based on diverting water to wet rice paddies. In New England I witnessed the development of more and more intricate water management obsessed with removing water from parking lots. While the control of non-point pollution from America’s ubiquitous asphalt parking surfaces has put us at some distance to water bodies in everyday life, it has also successfully contributed to the remarkable restoration of the Connecticut River Watershed as a whole.

However, the New England mill, like the Northern Thailand muang fai provided an example of direct engagement with water, but based on renewable energy rather than subsistence food production. Through this study I hope to develop design tools combining scientific knowledge about maintaining ecosystems, with socially resilience indigenous practices of adaptation and self-reliance.

Twin Storms

The ancient volcanic ridge of the Holyoke Range cuts across the Connecticut River between Northampton and Holyoke, Massachusetts, creating the famous oxbow scene for Thomas Cole’s seminal landscape painting View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts after a Thunderstorm. Like the river, Interstate Route 91 now cuts through the weathered ridge forming the northern edge of Jean Gottman’s Bos-Wash megalopolis, and travelers with skis strapped to their roofs know they are entering the heartland of rural New England when they pass through the Holyoke Range.

A similar feeling of arrival greets a driver from Bangkok when crossing the last ridge of mountains separating the ancient valley Kingdoms at Lampang and Chiang Mai, as one descends into the broad belly of the Ping River Valley into the domain of the ancient Lanna Kingdom in Northern Thailand. Teak forests give way to a fertile plain of villages, fruit orchards and rice paddies. A vast, intricate and indigenous irrigation network maintains a lush green carpet among a patchwork of new resorts and subdivisions, even in the dry months of the monsoon cycle.

By coincidence, cross mountain drives across both river valleys last year revealed the urgency of new design and water management practices to enhance urban resilience in the face of climate change. In August, 2011, I found myself traveling in the wake of the late season Typhoon Nok Ten, which dropped an unprecedented amount of rainfall across the already monsoon saturated mountains and plains of Northern Thailand. The storm triggered in the following months the most devastating flood in Thai history, crippling the high-tech and automobile industrial estates in the Central Plane north of Bangkok. I was back in the U.S. for less than a week when I again found myself driving in the wake of a devastating storm as I returned to New York on the tail of Hurricane Irene. Unlike Hurricane Sandy in October 2012, Irene spared the coast of the megalopolis from the feared storm surge, but like Nok Ten, Irene released an unprecedented amount of rain into the upstream watersheds, especially the Connecticut River and its tributaries.

While Cole’s painting is said to metaphorically depict the clash between civilization and nature, the scene depicting a severe thunderstorm about to descend on a peaceful agricultural valley depicts a very real event of ecological disturbance. The twin storms heightened my sense of urgency in discovering how the urbanized countryside in both Connecticut and Ping River Valleys might be designed to be more resilient in the face of unpredictable weather patterns. The initial study begins with close observations in the two sites in early spring through late summer of 2012.

This blog post takes the form of a photo-diary, beginning in April, the Thai New Year, in New England, then taking in the second-crop rice harvesting and new year planting cycle in Northern Thailand, before returning to the wet beginnings of late summer back home.

April, 2012, Enfield Commons, Connecticut, May, 2012 Ban Nam Rongkuhn, Chiang Mai

A dry spring allowed me access to Freshwater Brook, enabling me to conduct an initial survey of the various drains, catch basins, pipes, retention ponds and wetlands. A winter of snow removal and salting had ended the month before. Arriving in Chiang Mai at the end of dry season, it was time for stream dredging and embankment construction for flood control and second rice crop harvesting.

May-August, 2012 Ban Nam Rongkuhn, Chiang Mai, August 2012, Enfield Commons, Connecticut,

With the start of the monsoon, I had the opportunity to watch initial plowing and dike rebuilding and the first diversion of water to nursery rice paddies. Next the surrounding fields were plowed, and transplanting occurred just before I left in early August. Some fields were more simply planted with a broadcasting method.

Returning to New England during a period of end of summer thunderstorms, I was able to further investigate the effectiveness of the water management techniques used in the various parking lots at Enfield Square and Enfield Commons.

Chiang Mai’s waterways are hard working elements in a productive agricultural landscape, and could use some of the care devoted to the Connecticut River and its tributaries. However, Enfield’s parking lots could learn from the intricacy of the social networks around Chiang Mai’s muang fai system. Other than Black Friday, intense day of shopping the day after Thanksgiving, the lots are rarely fully occupied.

Rather than concentrating landscaping on the periphery of the asphalt, perhaps parking areas could form paddies, sometimes filled with cars, sometimes with water, sometimes used for agriculture, and sometimes with public events. Both sites would benefit from investment or reinvestment in micro hydropower.

Water is central to the nature of cities, as a source of productivity both economically and ecologically.

Brian McGrath

New York City USA

Add a Comment

Join our conversation