A review of A Sequel to Suburbia: Glimpses of America’s Post-Suburban Future. By Nicholas A. Phelps. 2015. ISBN: 9780262029834. MIT Press. 248 pages. Buy the book.

James Joyce suggested that the creative work of an author—and I also include the work of an artist or landscape architect—presumes the intellectual level of the audience that is needed to appreciate it. Having attempted to read Ulysses myself and come up short, the remark makes a lot of sense. After a few pages of author Nicholas A. Phelps 2015 book, Sequel to Suburbia my mind drifted to Joyce’s wisdom and to the question: For whom and for what purpose is this book intended?

The title Sequence to Suburbia is engaging, especially to a planner and landscape architect, like me, interested in the problems and the design potential of the unprecedented suburban pattern. The caption of the book that follows, Glimpses of America’s Post-Suburban Future, should extend the attraction to city planners, professors, or practitioners, implying that the book is forward-looking, useful, and will offer productive insight for one’s own work. On these points, the book will not disappoint, especially if the reader is familiar with the problem of the modern city and how to restructure it as a theoretical activity that is principally academic and research-tempered.

Enthusiasts of urbanism and landscape will encounter familiar issues and “contradictions” of suburbia in the forward and exposition of book. For example, the promise suburbia made for a new kind of civility that would be settled in nature but never materialized as garden, green and diverse mix of urban uses were replaced by optimized homebuilding strategies. But in addition to other, frequently alleged problems of suburbia, such cultural decentralization, lost human potential through travel distances and the consumption of natural resources, Phelps adds that some time after World War II, America as a whole gained from the movement of business out of cities, while the outer suburbs themselves barely benefitted, as simultaneously, the inner cities bore the cultural and financial costs. The familiar précis and recitation of topics sets up an expected delight and twist in the direction of the book.

Books about The New Urbanism such as The Geography of Nowhere, by James Howard Kunstler, or alternatively, counterarguments that are pro-suburbia such as Robert Bruggeman’s Sprawl; A Compact History, tend to polarize the debate with mercurial, and at times, snarky rhetoric. While Phelp’s research-driven exploration seems to lean towards the former in the beginning, the text takes an unexpected change of direction with the following.

Books about The New Urbanism such as The Geography of Nowhere, by James Howard Kunstler, or alternatively, counterarguments that are pro-suburbia such as Robert Bruggeman’s Sprawl; A Compact History, tend to polarize the debate with mercurial, and at times, snarky rhetoric. While Phelp’s research-driven exploration seems to lean towards the former in the beginning, the text takes an unexpected change of direction with the following.

Quoting Phelps, “Yet, if the Zeitgeist is of a sequel to suburbia waiting to be written by some architects, planners, and civil society organizations under the manifesto’s of a New Urbanism, TOD, smart growth, and the like, that picture is not one received by all. Indeed – and here’s the rub – arguably, the majority of citizens, architects, planners, politicians, land speculators, and construction, banking, and insurance companies are happy for the story of suburbia to carry on.”

What is perhaps the best contribution by the book, and one that recommends it as an additional to any shelf on the topic, is the realization that Phelps is studying suburbia with an open mind. In lieu of the pedantic or preachy, this transforms the book into something that the reader can appreciate objectively by considering that perhaps the question of suburbia isn’t a matter of replacement or the need for a sequel but rather its refinement. This is a refreshing counterpoint to broader debate about suburbia that in some cases can unfortunately descend into a kind of uncritical zealotry. Considering the author’s background, the writing style and prose that delivers the book’s objectivity may be a challenge for professionals to appreciate.

Nicholas A. Phelps is a professor of urban and regional development at University College London. A prolific writer, his online dossier indicates that he has written fifty-some books and published articles across a spectrum of major academic journals. It is interesting that Phelps wrote Sequel to Suburbia, since his primary academic field is economic geography, not planning or urban design. The statistics, quantities, and economics that dominate the intellectual world in which he dwells are unquestionably part of a city. But in a city, the quantitative co-exists with a qualitative realm that includes a vast and unmeasurable dimension of human emotion, wonder, and imagination. The two together make the true city.

Perhaps Phelps’s familiarity with his own quantitatively-driven field explains the impoverishment of drawings, diagrams, and the kinds of maps that one might typically expect in a text that outwardly appears to be about urban planning and design. If sensibilities, such as those reflected by The New Urbanism, represent a raison d’être, Phelps’s somewhat non-orthodox exploration of suburban planning and analyses of American suburbanism is heightened by his roots in English culture. Here he examines North American suburban patterns with the cool objectivity of a foreigner studying a specimen from a distance, versus, say, how an anthropologist might take on a similar project by living within a culture to more thoroughly understand the non-quantitative idiosyncrasies that can elude data collection.

The book is modest in length, which makes it approachable as a reading project. Eight chapters are organized onto 180-pages and a 51-page appendix that includes footnotes and an index to support them.

The overview in Chapter One advances the central question of the book: “While the shine has worn off the outer suburbs of the ‘first modernity’ (a term Phelps frequently uses, which is of his own invention) is there sufficient documentation and cultural agreement and intellectual consensus to glimpse the makings of a distinctly new post-suburbanity?”

From this point, the text proceeds with an admission that a cohesive field of suburban study and a nomenclature of its many vaguely defined parts has yet to emerge. In reinforcing this point, Phelps provides a useful enumeration of terms that have attempted to capture the essence of the spatial vagueness of the American metropolis and its different constituent elements, including:

- Galactic Urbanization

- Post-Metropolis

- Edge City

- Technoburbia

- Edgeless Cities

- Boomburbs

He concludes the exposition by offering that a recent—planetary urbanization—may “end the terminological proliferation”.

The next six chapters are organized into symmetrical sets of three that mirror each other in content construction. Chapters 2, 3, and 4 explore three distinct theoretical assessments of American suburbia by Phelps; they prefigure a set of case studies that demonstrate the same set of three assessments that continue in Chapters 5, 6 and 7.

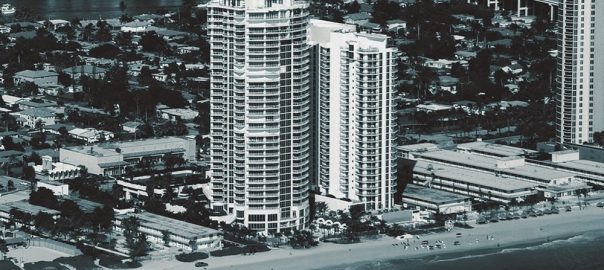

Respectively, the case studies are: Chapter Five, downtown Kendall, Florida near Miami; Chapter Six, Tyson’s near Alexandria, Virginia (formerly known as Tyson’s Corner until the city elected to reconsider its brand identity and drop the second word); and Chapter Seven, the expansive suburb of North Chicago, Schaumburg.

While the three case studies offer a kind of small, medium, and large geographical examination, their selection raises critical questions, especially in how Phelps points out that each example possesses somewhat unique qualities. It is curious that cities such as Phoenix, Houston, or Atlanta, which are textbook demonstrations of a vast and generic proliferation of suburbia that is unaffected or unmodified by the interference of geographical circumstances and natural features such as rivers and mountains are not included. And the musings of James Joyce became relevant again in considering the summary offered in Chapter Eight which leaves the question of suburban reform, revision or diminishment, open and inconclusive.

For whom and for what purpose is this text principally written? Clearly, it seems to favor academics and theoreticians doing research. Urban enthusiasts who are more accustomed to the flowering and nostalgic concepts of the New Urbanism will find this text turgid and frustrating when they encounter simple points enveloped in fog. Consider the following, “The prospects for the reworking of suburban space are crucially dependent on the extent and manner in which any rescaling of the state can address corollaries to private accumulation.” I understand all the words, but not when they are put together like this.

Those who expect that a new book about suburbia will reinforce their particular view of suburbia—either pro or con—even before turning the first page, may encounter a refreshing challenge. Wading through the rhetoric takes some work and persistence to reach the ultimate realization that Sequel to Suburbia, while skeptical of the topic on the one hand, remains open to the consideration that suburbia is an established cultural fact at this point in history, more in need of refinement than elimination. In this respect, the title, Sequel to Suburbia, becomes clearer as a question than as a declarative or imperative. To embolden the readers as their own arbiters sets the book apart as a text that is intelligent, refreshing, and useful.

Kevin Sloan

Dallas–Fort Worth

Add a Comment

Join our conversation