about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David's dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to "fall back on". So he bought a tuba.

Introduction

People like parks of all sizes—clean and safe ones anyway. They like trees and birds, even street trees and house sparrows, as they walk to work. Perhaps they are curious about the occasional dragonfly. Or at turns thrilled or alarmed by a coyote down the road. Enjoy the tranquility of a water course in a busy downtown. People like protection from storms too.

But do people see parks and birds and trees and the rest of urban nature (and its benefits) clearly enough to value them as elements of a well planed city? Do they appreciate the tree pits that suck up storm water? Do they celebrate the wetland that moderates storm surge and is a hatchery for game fish? Do they recognize cities as important sites of conservation?

Is the rich value of urban nature and its services—including economic value, social value, biophilic value, and conservation and biodiversity value—appreciated by citizens and policy makers enough to place them as co-equals at the planning table with transportation, sanitation, housing, and economic development? Do they understand nature as a key element of a city—their city—that is resilient, sustainable, just, and livable?

That’s where we need to be.

But most cities, and most people, aren’t there yet. What information or communications efforts or actions will it take to achieve an urban nature that is truly valued and visible to everyone?

about the writer

Simone Borelli

Simone is a forester and he works at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN as Agroforestry and Urban Forestry Officer.

Simone Borelli

Telling a good story

Everybody likes a good story and, at the end of the day, communication is telling a good, simple, clear, and truthful story. The difficult part is to ensure that you are telling the right story to right people and in the right way. Again, people love trees. There is no doubt that, when asked if they like trees and forest, everybody will answer “yes” without any hesitation. So, why is context critical, when you are trying to communicate and make sure that the community gains a better understanding of the value of the forest and trees that can be found in the cities in which they live?

Regardless of the context, having the benefits provided by nature recognized by the local communities is a key step towards their maintenance over time. Most urban dwellers, however, lack awareness of the key contribution that green spaces provide to their daily life. People living in cities, become progressively less familiar with natural processes and come to give for granted the services that the “invisible” natural environment provides. This is exacerbated by the fact that local communities are seldom engaged in the planning, design and management of urban green spaces. As a result, urban dwellers feel less involved and are less aware of the role that they could and should play in setting priorities for the place in which they live and ensuring that it becomes a “place” that they can call and feel their own.

So, how can we increase the awareness among urban and peri-urban dwellers, other stakeholders and policymakers of the roles and benefits of urban forests and other green spaces? How can this concept become an integral part of their lifestyle and encourage them to be “owners” of their green spaces?

There are many different narratives that have developed in various conditions and that could be included in an effective communication strategy. A powerful tool is that of creating green spaces in degraded areas of the city. In many situations, this has stimulated citizens to actively engage in the management and maintenance of these spaces. In Nairobi, Kenya, for example, a tree planting campaign launched in 2010 by the community of the slum of Kibera led to the planting of 10 000 new trees. The action was strongly supported by the local community, which saw in this action a first step towards an improvement of the conditions of their neighbourhood, making a space into a place for the first time.

This, of course, is not only true in extreme situations such as slums. Involving volunteers and both formal and informal community groups in tree planting and tree caring in public spaces can help raise awareness of the importance of urban forests, while also increasing community capacity in urban forest management (potentially reducing the cost of forest management in the longer term). Some of the better-known campaigns such as the MillionTreesNYC, in New York, were very successful in mobilizing urban dwellers to participate in volunteer group plantings in parks and other open spaces, or to actively engage in tree pruning, education, and advocacy programs. Providing free trees to citizens to plant in their own gardens has also proven to be an inexpensive and effective way of bringing attention to urban forests and trees, as well as other green spaces.

A different but also successful approach is that of certification schemes that has proven to be a very effective means for publicizing the environmental services provided by well-managed urban forests. In Celije, Slovenia, in 2005, the urban forest service and the local municipality launched the “Mestni gozd Celije”, a non-commercial brand aimed to raise local community awareness on the values of the urban forest for the city and to promote local sustainable tourism.

Social media, of course, are being used extensively and have helped sustain very successful awareness campaigns such as the Big Trees Project in Bangkok, which has played a crucial role in supporting the efforts to defend the remaining heritage trees around the city.

Social media, of course, are being used extensively and have helped sustain very successful awareness campaigns such as the Big Trees Project in Bangkok, which has played a crucial role in supporting the efforts to defend the remaining heritage trees around the city.

As a final consideration, it is always simple direct messages that seem to work best. A simple cartoon on the Benefits of Urban Trees that was produced by FAO has already been viewed by almost 400,000 viewers (in the 4 different languages).

about the writer

Sarah Charlop-Powers

Sarah Charlop-Powers is the Executive Director of the Natural Areas Conservancy, with a background in land use planning, economics and environmental management.

Sarah Charlop-Powers

There has been a sea change in public expectations for urban parks. The Olmsteadian ideal of pastoral landscapes comprising rolling meadows interrupted by lakes and fountains has shifted to a broader vision of urban nature that includes wilderness areas, green streets, and community gardens.

Our natural landscapes shape our cities

New York City frequently evokes images of skyscrapers and subways, but the legacy of natural landscapes continue to shape the city. Nature literally serves as the bedrock of human development. While geology has allowed for the construction of tall buildings in some neighborhoods, our coastal areas are characterized by glacial deposits, lending themselves to low-rise construction. Our historic wetlands, located along 500 miles of coastline, provided a historic buffer from flooding. Residents who lived through Superstorm Sandy experienced severe flooding along the coast, especially in areas where wetlands have been filled and altered.

Urban residents need nature

We know empirically that nature in New York (and other cities) is incredibly important for making cities cooler and more flood resistant; there are also many opportunities for urban residents to enjoy positive experiences in nature. Our recent research also shows that urban parks and the nature that they contain is incredibly valuable from a social perspective. In partnership with the U.S. Forest Service, the Natural Areas Conservancy conducted a survey of visitor perceptions of natural areas. In response to a question about where they recreate, more than half of the 1,600 people interviewed reported that they either spend time only in the park where they were interviewed (19.8 percent), or in another public park (36 percent). These findings support the idea that urban open space provides a much-needed outlet for residents, especially those who are less able to travel to suburban and rural locales for a break for urban life. Municipal parks departments and NGO partners are increasingly focused on expanding public programming and creating trails and other amenities that provide opportunities for safe exploration of forest and wetland areas.

Wildlife can thrive in city parks

Research increasingly shows the unique value that urban areas have as biodiversity hotspots, serving as key stopovers in long-range migration routes, as well as providing year-round homes for a surprising diversity of flora and fauna. In 2014, the Natural Areas Conservancy completed an ecological assessment that revealed incredible natural diversity within New York City’s forests and wetlands. Urban centers are frequently located in areas that are historically rich in natural diversity. In the case of New York City, the unique natural features that made the city’s location appealing for human habitation included a compelling combination of northern and southern species, ample game, and a mix of terrestrial and aquatic habitats, which continue to result in a high level of natural diversity. Our inventory of 10,000 acres of city-owned parkland revealed more than 750 plant species and over 60 unique habitats.

Looking forward

As we look to the future, we see that urban parks, especially those that are located in city centers, are frequently overcrowded, experiencing unprecedented levels of visitation. Luckily, less developed parks, frequently near residential neighborhoods, provide a meaningful alternative to overcrowded parks, and provide unique opportunities to spend time in nature. As we look to the future, I believe that we’ll see an increase in the value placed on urban natural areas, where people can engage in a broad range of recreational activities, and also appreciate the quiet and calm of time in nature.

about the writer

Hastings Chikoko

Hastings Chikoko is the Regional Director for Africa at C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group.

Hastings Chikoko

Fighting urban “green” criminals in African cities

In October 2015, a gang of 12 people murdered two men and raped a woman at Rhodes Park in Kensington, in the city of Johannesburg. The City of Johannesburg responded swiftly with initiatives to curb criminal elements in the city’s recreational facilities to ensure that the value of urban green spaces is not undermined. This has seen End Street North Park in the same city bringing residents to use the park for games, tournaments, and learning exercises.

The value of urban spaces in African cities is sometimes concealed by safety concerns. The fear of urban green spaces defeats the notion of social cohesion that most public spaces are intended for. In my life, I have had two encounters where my personal safety has been threatened at knifepoint. Both encounters happened in different urban green spaces that were created with good intentions—to provide recreation and leisure for people while addressing some ecological goals. My nasty experiences in these two urban spaces justify some reflection on crime in recreational facilities and what needs to be done to make urban green recreational facilities offer good life and not strife.

Urban green spaces are not made safe after they are created, so the solution to criminal elements in urban spaces does not lie in policing alone. The safety starts from people-centred designs of urban green spaces; this includes the understanding of social dynamics of the communities that the spaces are created to serve. There is a holistic package that needs to be considered in addressing public safety issues in urban green spaces and this package is wrapped in an envelope of community ownership and social relevance. This underscores the need to design the urban green spaces in a participatory manner with the communities that the spaces are intended to serve.

For me, a good urban planner is the one who locates an urban green space in an area where help is accessible. To me an urban green space should not be isolated from where the people are. It should be at the centre of the settlement and not adjacent or in the periphery of a settlement. That way, I still feel connected to the community even when I am engaging with the natural aesthetics of the urban green spaces. I also know that should my safety be threatened, help is only a shout away.

Linked to this is the absence of concealment. Designers should be able to include all the features of the park—including the shrubs and bushes without concealing my visibility for more than 10 minutes. Besides the shrubs and bushes, the landscaping and sloping of the park matters to me, too. Unless one is a professional mountain climber, it is not easy to run for safety in an urban green space that is predominantly steep.

Planned lack of concealment should also consider the possibility of my being audible to the community surrounding me. While a waterfall is a relaxing feature in an urban green space, a deafening waterfall does not guarantee safety, as my shouts for help will be obscured.

The number of people using the green space at any particular time minimizes concealment and creates a constant, visible presence. Increasing social and public activities in urban green spaces increases the number of “eyes-watching-over-me” factor, and makes me feel safe in the green space.

Green space designers should also know that I will not step into any “dark” forest just because it is located in a city, unless, of course, I have bodyguards. The placement of lighting in the park and the visibility the lighting provides (whether natural lighting or electricity lighting) informs my decision to use an urban green space.

To achieve all these, municipalities need to adopt an inclusive governance approach that goes beyond the parks, recreation, and environment departments. Different departments must be brought together to deliver every aspect necessary to enable the urban green spaces meet the social, economic and environmental needs, including safety.

about the writer

Marcus Collier

Marcus is a sustainability scientist and his research covers a wide range of human-environment interconnectivity, environmental risk and resilience, transdisciplinary methodologies and novel ecosystems.

Marcus Collier

Old-fashioned thinking

Recently, during the final meeting of the TURAS project, I was interviewed for a national newspaper. I was asked my opinion on a plan to pedestrianize a part of Dublin in front of Trinity College, known as College “Green”. Online public consultation documents have the usual mock-up of what this pedestrianization might look like, yet, despite its name, the images show only a large grey, open area. Not a shrub in sight!

To say the least, there was a lot of public reaction to the article. Amid all the palaver, it became clear to me that a sizeable number of people do not always value urban parks or trees in the way we imagine. It seems that these people do not “see” the same diverse social and ecological values as researchers and practitioners do. Greenery and trees can be threatening. So, how do we convey, or make visible, the tangible and intangible values of urban green infrastructure? One way is to follow the ecosystem service and natural capital route, such as moving to green roofs or sustainable urban drainage systems, which are capable of illustrating in real time how green infrastructure values can be economic and even aesthetic. Another way is through collaborative, co-created processes that draw on social capital networks, build new ones, and have an element of social learning. This can bring the message to a wider, less aware, perhaps less understanding audience. Focussing on the social values of green infrastructure, though, is very difficult to convey without a longer, more involved process.

Perhaps we should return to another “old-fashioned” technique that can be called on to illustrate values—show, don’t tell! When we demonstrated our new green living room in Ludwigsburg, and recently created a mobile version (currently touring Europe), people could directly observe the value of nature by seeing, touching, and smelling it. Nature-based urban comfort zones can fulfil multiple objectives, especially on a hot and noisy day in the city where users can immediately appreciate the relative calm of a green comfort zone. Couple that with beautiful and creative design as well as diverse plant species, and values increase. Urban dwellers really appreciate value when they can experience it for themselves—and frequently begin to demand nature-based solutions of their local authorities as a result.

Thus, it is on us, the academics and the practitioners, to take our curious findings—our working examples, our long-term case studies, and our strange, novel designs—to package them creatively and imaginatively, and to take them onto the road, literally. Bringing green infrastructure to urban communities is about winning hearts and minds, and can make nature-based solutions fashionable instead of intrusive.

about the writer

Sven Eberlein

Sven is a San Francisco-based solutions journalist and whole systems thinker committed to the advancement of ecologically healthy cities and a livable planet. He is currently the publisher and editor of The Art of the Green New Deal, a next generation journal of creative culture shift.

Sven Eberlein

Developing better urban habits

Why is it such a challenge to bring more trees and birds and parks into our urban environments when we know that most humans enjoy trees and birds and parks in their lives? Why is there so much resistance any time a major public infrastructure project is proposed that would daylight a creek, green a median, or turn a congested street into a butterfly sanctuary when nobody ever said they hated creeks, plants, and butterflies? Why are we so attached to an outdated, drab, and fossil-burning industrial-age concrete jungle when solutions are readily available to simplify, beautify, and green our existence?

Fear of change is a powerful emotion. Unfortunately, it takes only a few vocal people with strong attachments to the status quo to stonewall any kind of movement, no matter how beneficial it could be for the common good. The antidote to this fear of the unknown is to make the unknown visible, if just for brief moments and in small doses. This process is like turning on a flashlight in a cave to catch a glimpse of the beautiful paintings all around—once you’ve experienced a snippet of their beauty, you can imagine what it would be like if the whole space were illuminated. And being the social animals that we are, once we know how to shine a light on something new and inspiring, we want to share it with others.

The way to most effectively stage such a natural “interruption” of the regularly scheduled, dreary asphalt programming may vary from country to country and culture to culture. In the United States—a decidedly individualistic society with an innate distrust of government and authority—the most effective way to “change the program”, in my experience, is for individuals or a small group of creative and determined citizens to simply flick on the light switch.

For example, the wildly successful Pavement to Parks program in my adopted hometown of San Francisco did not originate in the city’s planning, public works, and transportation departments that currently jointly administer it. The seed for Pavement to Parks, which is intended to facilitate the conversion of underused spaces in the street into publicly accessible open spaces, was planted over a decade ago by urban visionaries at a small art and design studio (Rebar) who decided one day to convert a single metered parking space into a temporary public park on a plighted downtown street. Feeding the meter its maximum allowed parking time, they created a two hour green space and called it Park(ing).

As the photo of the intervention traveled across the Internet, Rebar began receiving requests to create the PARK(ing) project in other cities. However, rather than replicate the same installation, they decided to promote it as an open-source project, empowering others to create their own parks in their own cities and neighborhoods. This turned into PARK(ing) Day, an annual global event where citizens, artists, and activists collaborate to temporarily transform metered parking spaces into temporary public places. By 2011, there were 975 parks in 162 cities in 35 countries on 6 continents. In San Francisco, there are now over 50 permanent parklets, with new proposals being filed all across the city.

So what was it that broke San Franciscans’ old habit of assuming curbsides to be reserved for cars only, leading them to accept a new and officially sanctioned reality in which these spaces could be redesigned into public parks? For one, it took a small group of creative thinkers to re-envision a public space and boldly act on it. Secondly, a number of early adopters spread the idea, creating a necessary critical mass for accepting a new reality. Next, the installations needed to be localized, temporary, and fluid, giving the general public just enough of a sampling to inspire them, without feeling imposing. And finally, city agencies needed to step in at just the right time, seizing the momentum of maximum public support to enshrine the new vision into city policy and to normalize what had previously been unthinkable.

Old habits die hard. However, in urban planning, just as in our personal lives, they can be kicked to the curb if greener and healthier ones are visible, available, and within reach. Change is possible if we enact it together—creatively, and one step at a time.

about the writer

Niki Frantzeskaki

Niki Frantzeskaki is a Chair Professor in Regional and Metropolitan Governance and Planning at Utrecht University the Netherlands. Her research is centered on the planning and governance of urban nature, urban biodiversity and climate adaptation in cities, focusing on novel approaches such as experimentation, co-creation and collaborative governance.

Niki Frantzeskaki

Make time to connect with (in)visible nature!

It is a warm summer in Europe, and it is rather impressive to see how Rotterdam city looks during a heat wave. Experiencing 32 degrees C during August and 28 degrees during September, we are living more than 10°C of the average seasonal temperature. How does the city look? Booming with life: there are people everywhere enjoying the sun, enjoying the socks-free days. Walking in the city, people finally sit on the parks, rather than only walking through them or focusing on how to cut down walking time from home to work through them. But is this really a first opportunity to appreciate nature in the city?

At least in my city, Rotterdam, many people still romanticize nature as a picture from a Monet painting. Beyond the planned and planted perception for what parks are (Buchel and Frantzeskaki 2015), urban parks exist and thrive with biodiversity to be loved by many people in Rotterdam. But to realize what urban nature is about, you need to also “release” the small kid we all have inside us. Wanting to connect with nature, wanting to touch nature in its simplest “form” in cities, people wander in parks, meet in parks, and play in parks. In the sizzling summer we are having, I saw hedgedogs in the Warande of Brussels; I saw kids try to touch and hug seagulls in the Park (Het Park) in Rotterdam, rabbit families in Kralingse Bos in Rotterdam, and yellow snails in Zartpark in Breda; and I listened to crickets during the evening in Park Pwostancow Slakich in Katowice, Poland. For connecting with nature, time to connect is the first requirement, but you also need to give your attention: you need to listen, you need to see, to discover. In our overly communicative world, how many hours are we attached to our screens of all sizes, maybe missing the life that happens around us in the city? To connect with nature, seeing, listening, and being alert for all the experiences the city offers are paramount.

Is this an excuse to just be lazy? Maybe it is, maybe it is a way to find inspiration, to give time for nature, for inspiration, and for discovering the unseen sides of your city. Instead of queuing for a visit to a zoo, to see animals that do not even belong to the continent on which you live, maybe dedicate time to discover the open and often undiscovered urban habitats of life you have around the corner of your house.

Put time into making nature! Many people find gardening therapeutic, but it also goes beyond that. Get your hands dirty, have the passion to change your own land from emptiness to a green patch, to be excited when mockingbirds, parrots, and even owls come by. These represent investments in inviting nature, connecting with nature with your own hands. It is a welcoming act for a more “personal” connection.

But it is not just to make a personal connection with nature that is important; “making” nature in urban gardens established by communities goes beyond the personal and gets into the social. It is about finding new meanings of urban life, making sense of change and connecting with people and place simultaneously. Urban agriculture and urban community gardens are the places of socialization and political activation of urban communities. It is about considering how the actions of today connect with how we can change the future; it is about transforming today to shape the tomorrows of cities. So when you see the community gardens happening in your city, think of them as places to meet, to learn, and to connect with a pulse of change in your own city.

How can you broaden connections with nature? Inspire others by sharing your experience, by changing the stories of what quality time in cities can be. Set the example for those who work with you that discovery and time for connecting with nature and others is not time lost, but time well invested. And for those working closely with urban planners and decision-makers, simply bring them to nature in the cities, allow the connections to work for them and with them, show what the smart city strategies cannot buy and that nature in cities is the greatest investment and inventor of them all.

about the writer

David Goode

David Goode has over 40 years experience working in both central and local government in the UK and an international reputation for environmental projects, ranging from wetland conservation to urban sustainability.

David Goode

Understanding the role of nature goes far beyond its visibility

Talk to anyone in my town about nature in their neighbourhood and you can be sure that they will mention gulls, foxes, and probably badgers. Some see them only as a problem— things that intrude into their lives that need to be controlled. Others enjoy having wild foxes and badgers visiting their gardens and set up night vision cameras to record their activities.

Britain is known as a nation of gardeners and nature lovers. Membership of the Royal Society for Protection of Birds and the numerous regional Wildlife Trusts totals nearly 2 million. Local communities are involved in a vast number of projects to protect endangered species and habitats. But ask them about the issues and hardly anyone mentions green infrastructure or natural capital. These are words from a different language.

Where I live, people know that the city suffers from periodic flooding. Marks on the river wall record past flood levels together with dates. But I doubt whether most who stop to look will make any connection between these catastrophic events and the gradual loss of the natural flood plain as the city has become more and more built-up. River engineers are aware of the problems and there are plans to create a small flood alleviation scheme in the city centre. But the amount of land available to absorb floodwater is extremely limited. The frequency and intensity of extreme weather events are both predicted to rise as a result of climate change. We are already experiencing such episodes in the U.K., as evidenced by disastrous flooding of many towns and cities, where river levels have risen to heights never known before. Despite the colossal impact on homes, businesses, and local economies there are still immense political and economic pressures for local decision-makers to allow new developments and many of these will lie in flood plains. This is wilful blindness on a massive scale.

Designing cities to make optimum use of natural capital requires ecologists, planners, architects and engineers to work together to find sustainable solutions. Green roofs, living walls, and rain gardens are now well established as a new form of ecological architecture that makes sustainable urban drainage a real possibility. But this goes way beyond our everyday perception of nature; it requires an understanding of urban ecology—what makes things work and how we can make them work better.

Making the underlying ecology of a city visible to the wider public is far from easy. We can see Peregrines, and by watching we can begin to understand their story. But seeing the benefits of city green space and nature as an infrastructure supporting economics, health, and human well-being is far more complex. It requires evidence from all these fields. We, the professionals, have that evidence. It is for us to make the case. But we have a problem. Urban nature may be visible, but the processes are not. The vital functions of ecosystems are not readily appreciated until things go seriously wrong. In the meantime, when crucial elements are missing from ecosystems, their absence is rarely understood by decision-makers. We have to make use of every opportunity to publicise the value we gain for free from the natural world.

What will it take to persuade people to take nature seriously? Some opportunities arise in the wake of environmental disasters, when politicians are keen to take credit for new initiatives. Restoration of peatlands on British uplands to reduce the incidence of catastrophic floods many miles downstream is just one example. We can create our own opportunities too. This week there was a major public event in the Royal Festival Hall promoting London as a National Park City. It was packed full of reasons why nature is of value to Londoners. Dr. William Bird, a pioneer advocate of green spaces for health, argued that, “If we were able to connect people to nature in London and have increased access, it would have a bigger health benefit than almost any other intervention in public health.

Yes, we need to use both catastrophe and celebration, and with all the evidence that now exists there is no excuse for wilful blindness.

about the writer

Leen Gorissen

Leen Gorissen, PhD, is an Innovation Biologist and Sustainability Transitions Expert. She is the founder of Studio Transitio. By imitating & emulating nature, businesses and governments can design more efficient, effective and life-friendly innovation strategies that support rather than deteriorate life.

Leen Gorissen

On August 8, 2016, we began to use more from nature than our planet can renew in the whole year. The date at which human consumption passes this marker each year is now called Earth Overshoot Day, and it illustrates the alarming rate at which we extract resources from the Earth. We are exploiting nature to such an extent that we are undermining our life support systems by overfishing, overharvesting, and through deforestation—nature’s regeneration capacity cannot keep up with our pace of consumption. This mismatch in regeneration ability highlights the dramatic disconnect that has arisen between humans and nature, a disconnect that is reinforced by the trend that more people now live in cities than in rural areas, and by our design of urban habitats as concrete jungles crowded with technological distractions that imply we do not need nature to succeed.

However, we are not the only ones that build skyscrapers and cities. Termites, for instance, learnt to build high-rise buildings accommodating thousands of residents without overexploiting their environment. Instead of using vast amounts of energy to keep the inside temperature comfortable, they have designed a smart system of ventilation tunnels, a system that is far more energy efficient than our technological air conditioning systems. Coral reefs have developed underwater cities that use carbon as a building block instead of emitting it, thereby sequestering carbon in their building structures. Forests house an extraordinary variety of species and communities while producing benefits that are exported far beyond their borders, such as air production, climate control, and water regulation.

If we as a species want to endure and thrive on this planet, we will have to learn to develop solutions that work for instead of against life. Luckily for us, a new transformative and interdisciplinary field has emerged that is devoted to learning from nature and consciously emulates nature’s solutions to solve our problem of unsustainability. This field is called Biomimicry, after the words bios, meaning life, and mimesis, meaning imitating (Benyus, 1997). This discipline builds on the logic that nature has already solved many of the problems our societies are struggling with: energy, food production, climate control, benign chemistry, transportation, collaboration, and more. Mimicking these proven and lasting designs can help humans implement sustainable technologies.

Emulating nature’s organizational forms, processes, and systems can help accelerate our transition to sustainability (e.g. Baumeister et al., 2013). As Benyus so compellingly writes: “The organisms that surround us surf the opportunities in their habitat while respecting the limits, and in that frame, they perform what seem to us to be technological miracles. These tightly knit forests, prairies, coral reefs, tundras, and grasslands are the envy of all of us who thirst for a sustainable and equitable world. As a community, they not only create but continually heal and enhance their places. Our places, too. What better models could there be?” In other words, Biomimicry complements learning about nature with learning from nature. If we embed this new framework of inquiry in our educational, design, development and planning programs in cities, it can reconnect and re-align us with nature and offer us a new set of lenses to look at and value nature so that, like natural systems, we can start to create conditions conducive to life. Urban green spaces can thus be regarded not only as place to relax, but also as libraries of smart solutions that work on a finite planet.

References

Baumeister D, Tocke R, Dwyer J, Ritter S, Benyus J. 2013. The Biomimicry Resource Handbook: A Seed Bank of Best Practices. Biomimicry 3.8: Missoula. 280 p.

Benyus, J. 1997. Innovation inspired by nature. HarperCollins, NY.

about the writer

Cecilia Herzog

Cecilia Polacow Herzog is an urban landscape planner, retired professor at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro. She is an activist, being one of the pioneers to advocate to apply science into real urban planning, projects, and interventions to increase biodiversity and ecosystem services in Brazilian cities.

Cecilia Herzog

Safer, healthier, and more socially active urban spaces for all

Certainly people all over the world love parks, squares, and other open green spaces. But there are some essential factors to attracting and maintaining social use of these areas: they must be safe, comfortable, and filled with plenty of people (who attract more people). Many are not beautifully designed, but the ambience created by large trees, pleasant gathering sites, and nice pathways close to dense urban areas make those places a neighborhood magnet.

Once, I did a research project in one of the most attractive open spaces of Rio de Janeiro—Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon front—and when I asked why people loved to use the space, they responded that it was the beautiful scenery of the surrounding hills, the statue of the “Christ the Redeemer” on the top of one of those hills, and the water view. In spite of being simultaneously underneath a tree’s shadow hearing birds sing and beside degraded and eroded lagoon banks, with sewage smell emanating from the contaminated waters, and the noise of the heavy nearby traffic surrounding them, the park users noticed neither the good things coming from the local biodiversity, nor the bad things coming from of all types of pollution.

I was intrigued to know why they couldn’t see, feel or understand the multiple factors producing that local landscape context. I was concerned: if the park’s users liked things as they were, why would we need to change and improve the quality of their environment? To address this lack of public understanding, I, together with some fellows, founded the NGO Instituto INVERDE, which aims to educate and promote green infrastructure and urban ecology locally. We organized monthly lectures in one of the most beloved parks of Rio de Janeiro, Parque Lage. During more than four years, we invited myriad scientists, landscape architects, public officials, and researchers from many fields of knowledge related to the urban landscape. It was a great experience, and the response was really unexpected.

Then we started giving lectures and INVERDE gained recognition, becoming part of the Environmental Committee of the City of Rio de Janeiro. Together with some local public officials, I had the opportunity to organize seminars to educate and raise awareness about the work that was already being done by the Mosaico Carioca. Ultimately, our actions culminated with the first Green Corridor of Rio de Janeiro, under the leadership of Silma Santa Maria (head of the Conservation Units of that region), the design of EmBya Lanscapes and Ecosystems, and DeF, an urban design studio. The local residents became aware of the treasure they had next to their homes and became engaged, supporting and fighting to take the project forward. It was a process built from a win-win situation, even against the negligence of the city administration.

Social media is key in the process of education and raising awareness to protect and enhance urban nature. In the last few years, my writings for TNOC have focused on how people are falling in love with nature and natural processes via bottom-up movements that focus on urban food production, pocket forest planting rallies, urban trees planting and protection, and the reinsertion of hidden rivers and creeks in the tissue cities, and urban agroforestry, among others. Those movements are increasing in scale and expanding in Brazil. Lawns in parks are becoming targets of these ecological regenerative actions, and people are learning why they need nature in their urban front yards, local parks, squares, streets, or any residual space. These community members are developing new social skills. Collaboration is the key word that translates this new social behavior, which not only encourages people to praise natural features, but drives them to rethink their lifestyles, patterns of consumption, and waste production in all forms. Gradually, people are changing the very foundation of the money-oriented societies they live in. As a consequence, new forms of economy are rising, such as Instituto Chão (an NGO) in São Paulo, which successfully implements a solidarity economy focused on organic, locally grown, fresh food, which employs local people in its store and has became a staple in a trendy neighborhood of São Paulo.

As a result of these movements, a new ecological aesthetics is transforming not only public spaces, but residential gardens as well. For many people, cleaning is not an obsession anymore—they care for the leaves that fall and cover the soil, they compost organic residues to feed their plants naturally, they protect water springs in parks. As a landscape designer, I love these outcomes of working with nature and people to transform our common places with rich biodiversity—whether native or non-native, but productive—that attracts more and more people to this beautiful, life-based-movement. The consequence is safer, healthier, and more socially active urban spaces for all.

about the writer

Seth Magle

Seth Magle is the Director of the Urban Wildlife Institute at the Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago, Illinois. He has studied wildlife in urban areas for nearly twenty years.

Seth Magle

Valuing invisible nature

We are asked to consider the notion of a “truly visible” urban nature. I’d like to pose a glib question in response to this one, a question that simultaneously anthropomorphizes and oversimplifies the topic, and thus would probably give my scientific colleagues a collective heart attack. Does nature want to be visible?

I ask because much of it clearly does not. In studying animals, and particularly mammals, in the urban sphere, one is struck by the care they take to avoid detection by us. We can all point to the exceptions—the tree squirrels that chatter away from the safety of a tree, bounding here and there without evident concern for the silly primates below, the indifferent pigeons, and the like. But in North America, the coyotes, the rats, the foxes, the raccoons clearly do not want our attention. They go to great lengths—adapting to be more nocturnal, finding the least occupied portions of the city, watching carefully before crossing the streets—to avoid human notice. It is estimated that thousands of coyotes roam around Chicago, but in the very rare cases when one generates a conflict with humans, it’s worthy of local news coverage. The city is their home, and they will happily eat our leavings. But us? No, they have no apparent interest in being seen by us.

In fact, we have created evolutionary pressure on these species that ensures they remain concealed. A raccoon that makes a habit of scratching at people’s doors or tipping over trash cans is more likely to be the target of a call to animal control. The outcome of that call, in turn, will probably render that raccoon much less likely to pass his or her genes on to the next generation. Humans have generated a crucible that rewards invisibility, and so each new generation of wildlife gets a little bit better at evading us, even as they make their homes where virtually all of us are.

But clearly, the question posed to this roundtable isn’t about visibility in a crude sense. We are instead supposed to consider how to make people more aware of the animals that share their neighborhoods, invisible or not. But here, as well, we have a conundrum or two.

People call me frequently when they spot an opossum, or a coyote, or something else they didn’t expect moving through their yard. “What do I do?” they often ask. “Not a thing”, is my usual response. But they rarely find this satisfactory. Someone, they usually inform me, needs to catch it, move it. They have to do something. It does not belong here is a refrain I hear often. “It does, though”, I usually gently reply. “If you really want to do something, get a picture. Put it on Facebook.”

Sometimes this advice is received well. More often it is not. We are not always comfortable with the notion of visible wildlife intruding into what we see as a humans-only domain. It’s not just visibility we’re seeking. It’s not enough to simply know that we aren’t alone in the city. We need to accept it, to celebrate it, and then, perhaps, to carefully engineer it.

How do we create an urban nature that people are not only aware of, but rejoice in? This task is somewhat easier for wildflowers and oak trees than it might be for prairie dogs and little brown bats. People are not excited about the raccoon that makes a den in their attic, and with good reason. But what made the raccoon choose to do that? What is it about attics that attract raccoons? How many raccoons can an urban area support, what will they eat, and how do the answers to all of these questions impact hundreds or thousands of other species that interact with those raccoons? It takes more than just scientists to grapple with these issues; we need economists, sociologists, city planners, architects, and more.—not to mention much more space than is allocated for this thinkpiece.

From the science side of things, we work to generate this new urban nature through complex monitoring and analyses designed to understand urban wildlife behavior, and by so doing, determine how to build urban green space that both maintains wildlife and reduces human-wildlife conflict. This is what my colleagues and I spend rather a lot of our lives working on.

But from a psychological, and perhaps deeper, viewpoint, my hope is that we build this urban nature by inspiring a sense of place—an awareness that we all live in a form of nature, one with myriad unseen connections and interactions. There is ecological theater happening around us every day—animals are in a desperate hunt for shelter, for mates, for food, within a hundred yards of you, no matter where you are. It does not need to be visible to inspire.

about the writer

Polly Moseley

Polly Moseley is a producer and PhD candidate at Liverpool John Moores University, working on applied research on social and cultural values underpinning urban ecological restoration work in North Liverpool. Her first degree was French & English Literature from Oxford, and she is interested in linguistics and place-based narratives. Highlights of her career involve intercultural exchange with Grupo Cultural AfroReggae and street art with Royal de Luxe, and land artists in Nantes. Her current projects include building the Scouse Flowerhouse movement and preparing a public campaign for the restoration of a beautiful, heritage Library building. Polly has spent a total of 22 years on kidney dialysis and has dialysed in 180+ centres. She plays fiddle and loves wild swimming.

Polly Moseley

Until last November, I lived on the shores of Crosby Beach, which since 2006 has become synonymous with “Another Place”. This is the name of the artwork comprising 100 bronze sculptures conceived by Anthony Gormley and scattered over the 3km of sands and mudflats, with their foundations sunk into the depths of the earth and their heads rising above the waves at high tide. They cover a stretch which bridges the cranes and containers of the superport, with the far-reaches of Formby’s detached estates and red squirrel reserve.

Fernando Pessoa’s statement that “the function of art is not to be pleasant; art’s purpose is to elevate” seems all the more important when populism is masking, debasing, and corrupting public opinion.

Granby4Streets is a Community Land Trust in Toxteth, the ward up the hill from where I now live. Toxteth, like many areas of northern England, has undergone dramatic change involving demolition of many historic streets, and has lost many of its vibrant shops. Residents of several streets in the area resisted eviction and stayed and stayed for many years. Eleanor Lee is one of these residents, whom I had the pleasure of meeting this year, and who described two clear factors in bringing about the positive change which has gathered momentum over the last few years. The first of these changes is the street planting; the second was the market. The street planting came first and it is ad hoc and sprawling, humourous and joyful mixed with a hint of anarchy.

Granby4Streets is a Community Land Trust in Toxteth, the ward up the hill from where I now live. Toxteth, like many areas of northern England, has undergone dramatic change involving demolition of many historic streets, and has lost many of its vibrant shops. Residents of several streets in the area resisted eviction and stayed and stayed for many years. Eleanor Lee is one of these residents, whom I had the pleasure of meeting this year, and who described two clear factors in bringing about the positive change which has gathered momentum over the last few years. The first of these changes is the street planting; the second was the market. The street planting came first and it is ad hoc and sprawling, humourous and joyful mixed with a hint of anarchy.

Last year, Assemble, a collective of architects from London, won the Turner Prize—the U.K.’s most coveted fine art prize—for a Winter Garden concept within 2 of the terraced houses on Eleanor’s street. This concept is to conserve a public space, which will also be an artists’ residence space within the street, which is now being refurbished. Eleanor’s dream is for this handful of streets to become the greenest triangle in Liverpool and she is on her way to realising it. When questioned by national media, Assemble don’t claim the responsibility for this work. They credit the energy of the residents they worked with and, unusually, they even smile at the definition of being labelled as artists.

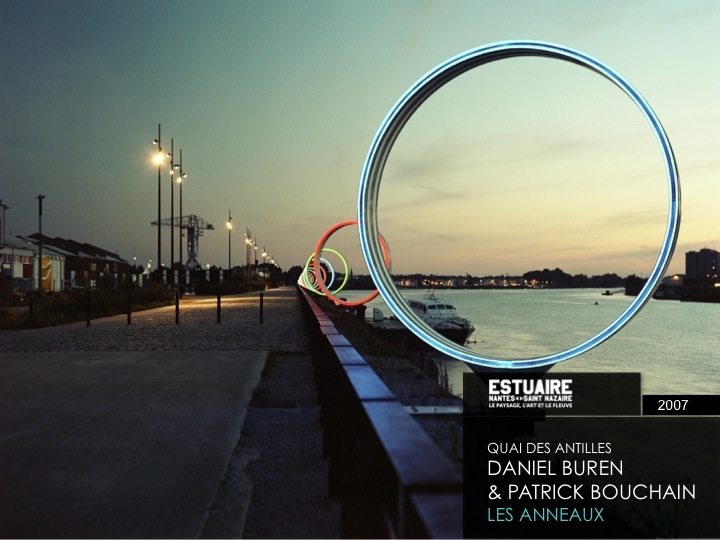

The French have never drawn lines between artists, gardeners, or chefs, and in a recent national poll, 15 percent of people equated culture with agriculture. Nantes, which was European Green Capital in 2013, has had a 20+ year trajectory with a civic leadership which prioritises arts, particularly street art. This has, in recent years, accelerated the popularity and importance of environmental policy and visibility of green spaces. From labelling plants growing out of cracks in pavements, to courgette mountains on roundabouts, a massive open-air cantine where you pick your own herbs, and the “stations gourmands” dotted along the river bank, Nantes has blended iconic artworks with inviting greening interventions, and has let the public take the lead in activating them. Lending frames through which people can take a different view and provoking action rather than prescribing it is surely a more sustainable way of making nature visible.

The work pictured above was a first move to reconciling the redundant shipyards on the Île of Nantes to the Loire Estuary. Reconciliation can be a function of art, though the timing and pacing of work is as critical as it is for conductors, choreographers and comedians.

The time it takes to build public-private sector coalitions has been vastly underestimated by the U.K. government. In Nantes, the duty of care for public space remains a clear public responsibility. The success of artworks to elevate debate about energy, about environmental issues, about adaptive environments and urbanism will only breathe if it is not prescribed, and if we harness the technologies available to artist innovators to fly with their dreams. I see in the hangars of Airbus the same creative forces at play as in the workshop of Royal de Luxe or the drawings of Jules Verne. Bridging the gap between research, innovation, art, and science—between human interventions and the outer realms of what is possible—is a collective responsibility.

about the writer

Ragene Palma

Ragene Palma is a Filipino urbanist currently studying International Planning at the University of Westminster, London, as a Chevening scholar. Follow her work at littlemissurbanite.com.

Jean Palma

Shades of green are medicine to the eyes and lungs in a congested, smoke-filled metropolis such as Metro Manila. A highly dense, built-up environment; millions of inhabitants; and a busy atmosphere require breathing spaces and green parks.

An interesting approach to integrating nature with design comes from one of the Philippines’ top estate developers. Ayala Land uses the biophilia hypothesis in landscaping, taking into account how people and nature thrive together. This is evident in how they use a variety of natural elements, from fishponds to flowering vines atop walkways. The firm’s use of native plants and trees better fits the local ecosystems, allowing nature to flourish without the need for adaptive maintenance.

Other efforts to make nature visible include bio-walls and vertical gardens along tunnels, footbridges, and arterial roads. These green elements are refreshing to look at against solid, cemented areas.

Landscaping, government initiatives, and legislation are very important in incorporating nature into any urban setting. But transitioning it into a cultural norm goes beyond the aforementioned pieces. The appreciation for nature and efforts of a household or community to incorporate greeneries and gardens into its environment go a long way towards putting urban nature on a pedestal close to issues such as resettlement, livelihood generation, and solid waste management, which are much-discussed issues in the Philippines.

While Filipinos are a people that are generally in touch with nature because of the archipelagic setting and the vast agricultural lands of the Philippines, a highly urbanized environment and the economic challenges of a developing country restrict communities from easily including plants and animals in their residences. Limited spaces, such as units as small as 18 m2 in condominiums, are dedicated to more practical house needs than creating pocket gardens that people find difficult to maintain, for example.

Awareness about the benefits of having nature as a standard element in urban areas—better health, less costs for infrastructure, and scientifically-based improvements in emotions and moods—should be encouraged. Initiatives to create “visibility” at a personal level may be small, but in a collective state, they create a sense of understanding and belonging among those who champion urban greeneries. Such projects also influence those who do not practice urban gardening because of the curiosity green spaces induce, and the aesthetics they display.

Best practices to increase green spaces should be encouraged in urban planning. These include urban agriculture, increased area allocations for garden parks in land use plans, and greenery programs in communities, among other strategies. The integration of these practices in land use and development plans, which are translated to tools of implementation at local levels, is critical to achieving visible elements of nature.

about the writer

Jennifer Sánchez

Jennifer works at Universidad de Costa Rica as a professor and at Parque La Libertad, an urban project from the Ministry of Culture as environmental educator.

Jennifer Sánchez Acosta

Working in an urban park to make visible the benefits of this kind of place is an actual part of my work. I can say that using this area to involve school students in outdoor sustainability education activities helps to make manifest one of the main social contributions that natural spaces bring to cities: raising awareness about the importance of sustainable development, and, more importantly, engaging students in projects and individual actions towards eco-efficiency.

Costa Rica is highly regarded as a green country; it is famous for its protected areas and its biodiversity, which our kids learn about at school. Children from both urban and rural parts of our country learn about the importance of conservation to ensure great benefits for our country and the world. However, in the urban areas, the importance and benefits of conservation seem to be invisible, since there is no “apparent” nature to be preserved. That’s why, recently, many NGOs and some other civil organizations have been working in introducing urban residents to the natural environments found within cities.

People care about the history of the parks; they like to know how old the trees are and to hear about the conservation objectives of the place. They need to be taught about the direct benefits of having such places as part of the city. We work hard to rescue and recreate the natural environment of San José and to encourage citizens to engage in practices that are being forgotten, such as growing one’s own vegetables, taking care of one’s garden, and rescuing communal areas to turn them into natural places that the whole community can enjoy.

I’ve learned that one key action to making nature more “visible” is to introduce people to the spaces—not just building or preserving “green places“, but getting people to relate to the place. To achieve this, we need to bond people to the parks by incorporating elements in the parks that help people bond to them, while planning the design of new spaces into which we can incorporate historical and social elements that appeal to users’ interests, and, in spaces that have already been built, by implementing strategies to increase their appeal.

I think parks and other natural areas in the cities need to speak directly to people. We need to work face-to-face with groups of people interested in learning more about these spaces and letting them help us to engage more and more people in the use of our parks. The immediate benefits are tangible: I often hear people saying that being at the park makes them feel relaxed, helps them to connect to nature, and that they enjoy their time outdoors. It should be easy to incorporate into those feelings an appreciation for all the benefits that nature gives our cities.

about the writer

Richard Scott

Richard Scott is Director of the National Wildflower Centre at the Eden Project, and delivers creative conservation project work nationally. He is also Chair of the UK Urban Ecology Forum. Richard was chosen as one of 20 individuals for the San Miguel Rich List in 2018, highlighting those who pursue alternative forms of wealth.

Richard Scott

We live in challenging times for green space. The U.K.’s Green Belt, which rings our cities, is up for grabs, and is gradually being picked over. We find ourselves having to straddle fences to make a stand. Our green spaces are becoming globalised like High Street fashion, as experiences are standardized and our world is dumbed down—or they just get built on. As in evolutionary theory, it’s order out of chaos, seeking ways to build landmarks to change mindsets and raise aspirations.

It is important to pass energies between places and build real collaborations, rather than just sharing logos. Recently, we have made some headway on this, with our own Tale of Two Cities flagship project in Liverpool and Manchester. These areas, which suffered mass demolition and mass transit, have witnessed major social upheaval and have huge stories, from the potato famine and the decline of the docks, to the origins of Rolls Royce and post-industrial change.

The best bits are the things you really remember. The seed sowings, when we heard the songs for the first time, or the simple exchange of wildflowers between a Liverpool and a Manchester School. The smiles, moments of laughter, embarassments, heroic failures (occasionally), and real success stories. It’s about life stories, and sharing them, and adding them up to link to other people who can do the same. This way, you can dive deeper into ecology and its complexity from a simple seeding.

When we met and were influenced by “Landmarks” author Robert Macfarlane, we saw that making nature visible is clearly about a magical way of responding in language to ideas of nature, place, and landmark in respect to conversation and surroundings, inspiration, and self-pilgrimage. It’s a playful thing for children or just anyone feeling free enough to reflect and observe the world and dare to invent a new word, rather than just accepting the world as frozen—as we can easily do, through the notion of seed banks and collections, which are important, but which touch few, or don’t grow anything.

This links back to a Time of Gifts, when the gift was the beginning of a journey, and reflection on where this can take you. The idea of generosity of spirit and sharing that places and people bring together is an enormously strong mechanism to make things happen, and ignite the imagination. It’s extraordinary what people can gain from knowing the name of a plant and telling its personal story and being fascinated by that. Ultimately, green spaces in cities are about being kind, to nature and ourselves.

It is often healthy to try and grasp what made something fresh and important in the first place, to remind ourselves of that whilst working to stimulate others. Often, it is the delight of a transforming moment which gives people the feeling of being part of the world, like a fleeting moment reflecting with a rare animal or butterfly. These indefinable, enabling moments hold the power to define the way individuals respond and react to green space in a way that transcends normal experience.

As the world leaps urban, it’s the urban places that have the key to the future. This is why it’s so important to connect the hot spots of energy and talent. Tale of Two Cities has been so important because it has reached more people as active participants and passers-by than any other work we have done. By drawing on the assets of two proud neighbours, with their wealth of trade, sports, and cultural links, the flowers have enabled us to orchestrate exchanges between large organisations, grass-roots charities, and individuals with flair.

The sparks can fly, and suddenly personal connections we made with China are informing a new Wildflower Centre in Chengdu, which has grown 54 species of wildflowers released from Kunming Institute of Botany to enable similar creative projects in one the world’s fastest growing cities.

In the future, fewer will have the countryside on their doorstep. We need to both play with nature and take it seriously. We all too often contain and bottle ideas rather than running with them. The most inspiring places are where people have been able to do that for a long time, like Nantes and Amstelveen, places which ratchet up work to set real gold standards.

Most importantly, it’s about the warmth of connections and the way we make our days count, without being discouraged or distracted, and the need for individuals and organisations to work flexibly to collaborate and deliver. We just produced a seed packet for an arts project in Liverpool called The Liverpool Perennial, with artwork by artist Jamie Reid, who produced the iconic sleeve for Anarchy in the UK by the Sex Pistols.

We have to make nature visible if the world’s wilder places are to have a chance and society to reap joy from the benefits. As we build a new Northern Flowerhouse here in the Northwest, it is about creating movements, and taking the Flowerhouse principle to the Northern Hemisphere.

about the writer

Chantal van Ham

Chantal van Ham is a senior expert on biodiversity and nature-based solutions and provides advice on the development of nature positive strategies, investment and partnerships for action to make nature part of corporate and public decision making processes. She enjoys communicating the value of nature in her professional and personal life, and is inspired by cooperation with people from different professional and cultural backgrounds, which she considers an excellent starting point for sustainable change.

Chantal van Ham

With a growing urban population, the benefits of nature both for quality of life in cities and to respond to challenges such as climate change, drinking water supply, and health are becoming clearer and clearer. Not many cities and their citizens are truly aware of the values of nature for their futures. What sets the cities that do make the connection with nature from those to whom nature is invisible?

Some of the messages I took home are that there is a clear connection between nature, culture, and development that is all too often overlooked, and which is essential to finding common ground in a spirit of partnership and collaboration.

Green roofs, bird-friendly building design, natural landscapes that work with indigenous plant species, urban trees, and urban agriculture are all equally valid ways to attract attention to the valuable services that nature provides to cities. However, to attract attention to the services of nature, there is a need for a broader perspective that connects the urban landscape with the ecosystems surrounding it, integrates nature within planning and decision-making, and gives a voice to the ideas of citizens.

In the context of severe water scarcity in Brazil, São Paulo state has committed to restoring an ambitious 300,000 hectares of degraded land by 2020. As part of the restoration programme, the government is working to improve water quality, to increase access to water by restoring 20,000 hectares of riparian forest in the state, and to recover springs. This initiative demonstrates how a political decision that unites different actors, such as public and private companies, public power, and civil society can lead to effective investments in natural solutions, bringing multiple benefits to water-stressed cities.

Urban parks are at the heart of connecting citizens with nature in cities. Chapultepec Park is to Mexico City what Central Park is to New York, with 18 million visitors annually, 60 percent of which are families. A citizens group, together with city officials and park administrators, set themselves the goal of creating a master plan to preserve, restore, and remodel the park. In a unique effort for Mexico, half of the funding for restoration was collected from individual donations, including one million donors at metro stations and supermarkets. This shows clearly how much citizens value nature in their cities and what their participation in urban planning and development processes can lead to.

One more example related to the world’s water crisis that I would like to highlight is a new conservation and impact investment model developed by The Nature Conservancy called Water Sharing Investment Partnerships (or WSIP). Sustainable water management will mean reducing consumptive use without compromising economic returns or crop production. This will require strong government leadership and a well-functioning water market. Such a market can provide financial incentives for improving water’s productivity by enabling those willing to use less water to be compensated by those who need more water, or those who want to return water to the environment. Such a system can only work if there is a good understanding of the value of nature and a willingness to act to give water back to ecosystems in order to ensure the sustainability of water supply.

NatureForAll is IUCN’s new global movement founded on a simple idea: the more people experience, connect with, and share their love for nature, the more support there will be for its conservation in the future. I hope this will provide some new inspiration and collaboration to make nature part of everyone’s life, bringing together different worlds, as only jointly can we create more visibility for nature.

about the writer

Gavin Van Horn

Gavin Van Horn is the Director of Cultures of Conservation for the Center for Humans and Nature, a nonprofit organization that focuses on and promotes conservation ethics.

Gavin Van Horn

From visibility to voice

“There! There!” Every summer now in Chicago, my son and I tune into the otherworldly buzz of cicadas. They play built-in tymbals on their bodies, marking the season with courtship crescendos that rise and fall through waves of humid air. It would be hard not to hear them in my neighborhood when they reach their symphonic peak. Seeing them is somewhat trickier. But once you put your nose close to a trunk, get eye-level with an exoskeleton still fastened with a pincer-like vise to the underside of a tree limb, you probably won’t be able to stop seeing them. “There! There!” my son shouts, and we marvel at the world abuzz over our heads and the many lives active under our feet, where the next round of cicada nymphs will quietly bide their time until summer returns.

This gets to the heart of the question of visibility, which is a matter of more than what is within eyeshot. For anything—any person, any other creature—to have value, we must first be able to “see” this being as a subject, something that has its own interests, its own claims on our shared place. Visibility is drawing what is otherwise inconspicuous to us into the sphere of our moral attention. This simply means “seeing” something as a member of our community—not just just as background noise, but as an important voice in our decision-making. Not just as background scenery, but as a visible character within our story.

Making urban nature visible and valuable depends on storytelling. Writer John Tallmadge captures this understanding well with the following observation: “So much of the quality of our lives depends on relationships, which can’t be weighted, measured, quantified, or even directly observed. We use stories to make them visible” (p.24, in The Way of Natural History). Stories, at their best, crystallize what is most meaningful to us. They orient us and hold up a vision of the world—an ethic for how to live well. They make the unquantifiable visible.

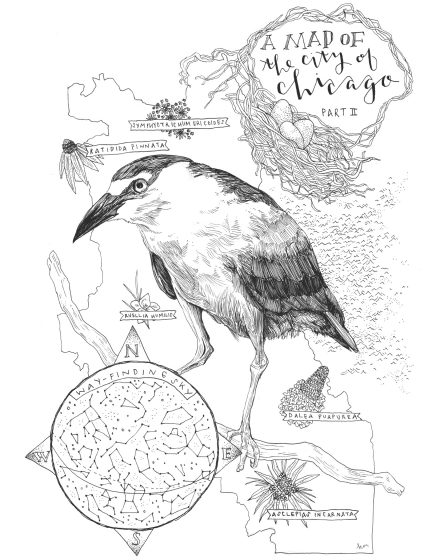

I’d like to share a pair of maps that demonstrate how stories of urban nature can change. When my friend and illustrator Keara McGraw moved from the suburbs to Chicago, she brought with her a fairly common set of assumptions about the relationship between nature and the city. In one of her illustrations, she captures a number of presuppositions many people have about the city, whether or not they are conscious of this.

As you can see, the outline of Chicago’s city limits serves as the container for a lot of emptiness, other than the “cement,” “smoke,” “buses,” “trains,” “pollution,” and “smog.” In this depiction, you need to get away from the city to find “lots of nature and stuff.” Without a proper counter-story, I’m afraid this is the mental map of urban nature that many people continue to carry in their minds.

To Keara’s credit, she was open to seeing new things. Perhaps because she’s an artist, she knew how to “be there,” present to the grace and beauty that was once obscured by or absent from her mental map. Once she began learning about the plants and animals that make this city such an exciting, life-affirming habitat for so many, her map changed.

Keara’s new—and by no means final—map reveals a completely different understanding of the city. The central figure in the map may be familiar to those who know their birds. Black-crowned night herons are a state endangered bird in Illinois. They once nested on the far southeast side of Chicago, but now have moved their colonial nesting arrangement to the heart of Chicago, a mere 2.5 miles from downtown. By all accounts, they are thriving. By the hundreds. Their rattling qwawks and croaks fill the urban tree canopy every spring through fall as they hatch and fledge their young. The herons are living reminders that nature can flourish in our cityscapes.

Just like Keara, we all have mental maps. Our stories draw the lines on them, tell us what to expect, what’s possible. Where nature can be found.

In a book I co-edited, City Creatures: Animal Encounters in the Chicago Wilderness [reviewed at TNOC here], one of our goals was to further a re-storyation of Chicago. We invited our readers to see Chicago, and all urban areas, as multispecies communities. If we perceive our own stories as entangled with the lives of other creatures in the city, we’re more likely to consider their needs, bear witness to their struggles, and take them into account in decision-making, whether that involves planting milkweed for monarch butterflies, designing buildings in a way that discourages bird strikes, or restoring large habitats with other species in mind. Stories may be our most ancient and possibly best means of fostering empathy. They engage our imaginations, creating a space in which we can consider the living realities of others.

A final point: from visibility and value emerges voice. Stories of place that reveal urban areas as lifeworlds—as valuable shared habitat populated by multiple unique and curious subjectivities—can change our mental maps. The show goes on with or without us, whether or not our mental maps are attuned to urban nature. But if we do want a more comprehensive story of place, one in which other species are central to our mutual thriving, this requires not only telling stories—making visible—but listening. Voice. I hear the cicadas again. The voices are all around us.

about the writer

Mark Weckel

Mark Weckel is a conservation scientist and manager of the high school Science Research Mentoring Program at the American Museum of Natural History

Mark Weckel

City kids’ perspectives on making the green more visible in the gray: equal parts media and education, and a dash of force

I would imagine that for many us—readers of and contributors to TNOC—we think about how to make urban green nature more obvious and relevant all the time. But we are both the preacher and the choir. We are the converted. Whether it is innate or learned, we accept the idea that nature humming through our cities is as normal as the rumble of its subways (and in both cases, we always want more!).

Today, I am a conservation scientist at the American Museum of Natural History, where I manage the Science Research Mentoring Program (SRMP). Each year, 60 NYC high school students have the opportunity to join the lab of one of the Museum’s researchers. As an initiation into SRMP, the class spends a week at Black Rock Forest, just north of the city in the Hudson Highlands, hiking (a lot), turtle trapping, star gazing, and bird watching. It’s new, scary, and tiring. It’s also the best damn thing they’ve done all summer. The only complaint I get—every year—is that they only get to go once as part of the program.

So, using my captive audience of city kids, I did a little research to help me answer this round table’s question: how can you sell green nature to an urban audience? How can you make the public need more of something that many didn’t know they wanted? After our trip to Black Rock, I asked all of the kids if their experiences had changed their perception of nature, and what they thought could be done to make green nature more visible to their friends and families back home. Here’s what they had to say:

A bigger and wilder Central Park: Central Park occupies the premier spot in the Pantheon of NYC parks. And for good reason: we are still looking to Vaux and Olmstead’s 19th century visionary masterpiece for 21st century solutions to the Anthropocene. While there are many other parks to learn about and love, Central Park will always be a flagship—and therefore a symbol—of our ideals. My kids wanted to really push the envelope: make it bigger and “wilder” to showcase urban biodiversity, big and small.

1Million Trees is not enough: Although students were familiar with NYC’s successful afforestation effort, they wanted more regular opportunities for observing biodiversity. A few of them of suggested sidewalk meadows (Million Meadows project, anyone?) replete with habitat for butterflies and grasshoppers.

The Need for a Media Blitz: Several students gave suggestions that are already in place (e.g. NYC bird walks, or hiking trails through “Forever Wild” areas). Perhaps that’s why they also pointed to the need for more PR highlighting NYC’s natural wonders. Students suggested signage similar to those you’d see on nature trails, but along sidewalks highlighting facts about street nature. Subway ads might be a good way to go, too. Perhaps the ubiquitous green and red stick figures that tell New Yorkers that poll dancing is not acceptable subway etiquette could teach us about quirky NYC natural history, from our once famed (and now rebounding) oysters to our Gotham whales.

DOE: Put NYC Parks in your curriculum – So many of my students wished that they knew more about NYC nature as children. They argued that visiting parks and observing their flora and fauna should be part of the Department of Education’s core curriculum for elementary schools. Students should not just learn about ecology; they should learn about NYC’s ecology. And it should be immersive. As one student said, “Hiking for four days, staring at the night sky, setting your feet on the bumpy rocks, and jumping through streams . . . I was interacting with nature closely, not just observing it.”

Resort to force – Somewhat unexpectedly, several students said we need to find ways to force people out of their comfort zones because Black Rock had forced them out of theirs (Disclaimer: we don’t force our student to do anything! Picking up a millipede or wading through muck to check a turtle trap is all voluntary). Said one student, “Despite the fact that I’m still not keen on insects, I feel that being in the forest and surrounded by them for a few days, I’ve grown more accustomed to them and I can only imagine how I’d feel after more time in the forest.”

These suggestions came from students still on the high of their week at Black Rock. As with my experience in Belize, leaving the city interrupted their normal life and provided the distance, stimulus, and discomfort necessary to reflect. Hopefully, they will bring some of this newfound appreciation back to NYC. However, as close as Black Rock is to NYC, it’s not feasible to lead transformative disruptive excursions for 8.5 million residents. Whether my students’ ideas are practical is debatable; however, we will need more of this creative brainstorming from New Yorkers from all walks of life as we look to bring micro-transformative disruptive excursions to their everyday existences.

about the writer

Mike Wetter

Mike Wetter is Executive Director of The Intertwine Alliance, where he leads a coalition of 112 organizations working to integrate nature into the Portland-Vancouver region.

Mike Wetter

Lessons from an urban alliance: three ways messaging about nature is different in cities

As a coalition of more than 150 organizations, resident engagement with nature is fundamental to our mission. Here are three things we’ve learned in our ten years of work on this topic:

1. Start with what they already value