What if urban resource management and conservation reflected not just the politics and science of the day, but were rooted in creation stories, place-name stories, and personal stories about the relationships people have with place? This kind of thinking is at the heart of traditional ways of stewarding the environment in many remote and rural place-based communities around the globe, but could it also be done in urban settings? If so, how?

Hawaii’s lessons for navigating Island Earth

In September 2016, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature World Conservation Congress took place in Honolulu, Hawaiʻi, the first time it has ever been held in the U.S. Through ceremony, hula (dance), and mele (chants), the opening ceremonies reflected the kinship that people from Hawaiʻi have with land, sea, and sky—and they set the stage for two weeks of events attended by world leaders in the policy and science of conservation.

My time living and working in areas rich with biocultural diversity—such as Hawaiʻi, Tanzania, and Fiji—has taught me the value of promoting and applying local knowledge for addressing health care, conservation, and adaptation to global environmental change. More recently, my thinking about the value of applying particular, place-based ways of knowing has expanded—beyond the places in which these knowledge systems originate and into areas that, on the surface, look quite different, such as cities. The reflections I share here grew out of my participation in Hālau ʻŌhiʻa, the only formal professional and personal development training program in Hawaiʻi stewardship practices for stewards of Hawaii’s Islands’ well-being.

Braiding together personal, professional, and spiritual development

Engaging in this experience elevated the concept of braiding together the personal, professional, and spiritual aspects of life as a real practice, and it also shed light on an ala (pathway) to get there. Although this integrated approach is a foundational concept for many place-based and traditional approaches to environmental stewardship, the scientific approach most of us were trained in deliberately avoids such integration in the name of objectivity. The cover of our training manual reads, “Deepening our connections for the wellbeing of ourselves and honua [planet].” It begs the questions: how can we as individuals be well if our surroundings (people and environment) are not? And how can our surroundings be well if we are not? Starting from the idea that people and place, biology and culture are intertwined and synergistic means operating from a “biocultural axiom of aloha.” I believe this core principal of our course has the potential to inform natural-cultural resource stewardship beyond Hawaiʻi, including and especially in densely-populated, urban, culturally diverse places.

With support from the U.S. Forest Service at the Institute for Pacific Islands Forestry (Hilo, Hawaiʻi), the course was created and taught by Kekuhi Kealiikanakaoleohaililani, an esteemed kumu hula (teacher of hula), Director of the Edith Kanakaʻole Foundation, co-creator and Assistant Professor of the I Ola Hāloa Center for Hawaiʻi Life Styles at Hawaiʻi Community College and more. With the recognition that “natural resource professionals in Hawaiʻi recognize that effectiveness of and personal satisfaction from resource management can be enhanced by integrating multiple knowledge systems into all aspects of the management process,” Kekuhi formed Hālau ʻŌhiʻa. Her invitation letter described the program’s goals—to “both foster a working knowledge of Native Hawaiian perspectives on resources and resource management, as well as to enhance relationships among members of the resources community, such as managers and staff, community members, researchers, and the resources themselves.”

The course was held in the spring and summer of 2016 for one full Friday per month for four months, a weekend immersion experience, and a half-day exhibition to share what was learned with colleagues and family in the fifth month. The majority of participants came from non-profit organizations, government agencies, and educational institutions concerned with resource management.

Some course participants had Hawaiian cultural backgrounds, either by genealogy or by being born and raised in the islands. I have neither, although having lived and worked in Hawaiʻi for almost twenty years, I have developed an understanding of aspects of Hawaiian culture and language. I entered the course with a deep appreciation for this reservoir of information, and realize even now that I have only scratched the surface. I would say, regardless of cultural background or experience, as people who live, work, and care about Hawaiʻi, all of the participants in Hālau ʻŌhiʻa are invested in learning more about Hawaiian perspectives, culture, and traditional ecological knowledge. I left with a greater sense of purpose, more informed and equipped to see and engage in relationships with the social and ecological characteristics of communities in Hawaiʻi, and beyond.

Over the past two years working as a U.S. Forest Service Social Science Researcher with the New York City Urban Field Station, my team and I have been cultivating an understanding of how place-based and traditional ways of knowing can inform natural-cultural resource managers, researchers, and educators more broadly, including in cities. We have been asking: what would a biocultural approach to sustainable resource management look like in New York or another major city? How would it be translated? Would urban resource managers and researchers be receptive?

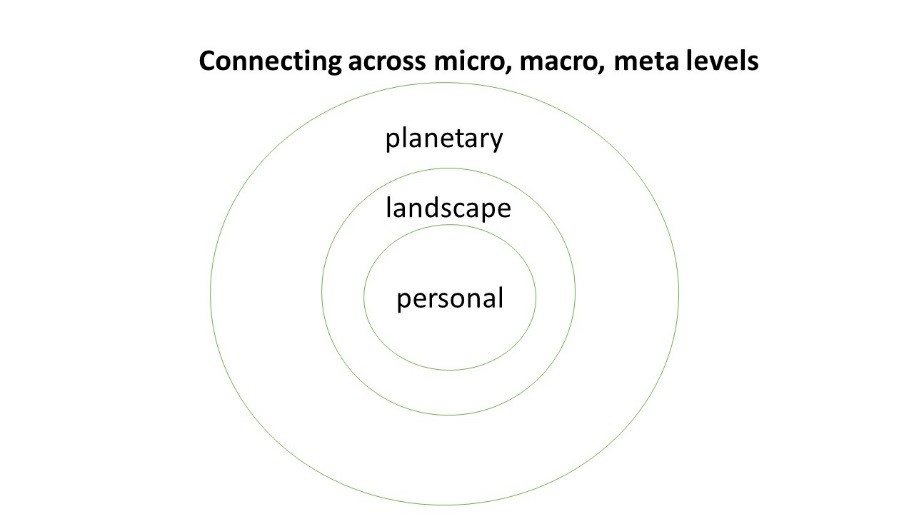

Connecting across micro, macro, and meta levels

In addition to thinking about connections across personal, professional, and spiritual levels, Hālau ʻŌhiʻa has inspired me to think about connections across micro, macro, and meta-levels. In the Hawaiian language, these are: kiʻi ʻiaka, kiʻi honua, and kiʻi ākea (at the personal level, the landscape level, and the level of planetary consciousness).

We began by applying this framework to understanding various koʻihonua (cosmology) and kaʻao (myth, conscious awakening) from around the world. Kaʻao are windows into other people’s worldviews. Common themes they share across space and time are: creation, recreation, and rebirth, among others. A theme that particularly struck me is that “the sacrifice becomes the creation,” evident in a number of kaʻao. We read and discussed accounts from the Arctic that relay the fate of Sedna, whose fingers were chopped off by her father Anguta as he threw her over the side of his kayak into the sea. Her fingers became seals, walruses, and whales, foods on which Arctic peoples rely. We listened to the Norwegian account of how Ymir was killed by his brothers, who then used his corpse to create the world—blood became oceans, skin and muscles became soil, hair became vegetation, and so on. Many of us are familiar with biblical stories of creation and sacrifice, which were also discussed as kaʻao. It was more than fitting to have this conversation in a landscape where Pele, the Hawaiian Deity associated with volcanoes, continues to take away and create land through the ongoing activity of Kīlauea.

I thought of my own experience giving birth and the sacrifices all parents make for their children, but this discussion also conjured images of a seed and its development. Who could imagine that by splitting open its own skin, and seemingly self-destroying, that a life force thousands of times larger and stronger than the seed itself develops? As a class, we discussed how these stories also teach us about what we have in common, how we see the world and our place in it. Kaʻao are important for all of us, including resource managers, because they influence how we see our relationships (responsibilities and rights) to places, and therefore how we care for them (or not). In other words, they influence stewardship behaviors.

If we see places and their features as family, and recognize that a great grandparent, parent, and child are family members as much as a mountain, stream, and ocean, then the relationships are quite profound, as are the responsibilities we feel to them. In the words of Kekuhi, the relationship between people and land needs to be based on “kinship” rather than “commodity” if we are to live sustainably. As a class, each of us researched, memorized, and recited our genealogies, which situate us within our ancestral and landscape kin relationships. I described my generational connections to my Solvenian great grandparents, my Polish grandparents (via Chicago), and the mountain, stream, and watershed where I live now on Oʻahu.

Taking this a step further, what if we recognize that we are not just related to but a part of and even the same as the landscape and water features, plants, and other animals that surround us? This concept of kincentric ecology is also echoed in many longstanding traditions around the world. Kekuhi wrote, “Because we possess the same subatomic structures that stars, earth, ocean, air, plants, and all manner of animate and inanimate forms, is it not natural for kanaka to constantly change as well?” If you see yourself as equal to another being, you are more open to learn from it rather than about it in an objective way.

If the kaʻao of a particular place and its original people is not readily accessible, one could expand and go more regionally, or think about the kaʻao in a more contemporary context. As a framework for outreach, researchers and managers could ask: What are the kaʻao of the people connected to that place today? How did they get there? Where did they come from? Who are their families? Their watersheds? Their mountains, trees, and waters? Are these elements the same or different from “home”? What are their accounts of sacrifice and (re)creation? In what ways are people sustained by their natural environments and by urban green space? What elements or characteristics are as valuable as their own family members? Open community meetings to share these stories in the early stages of engaging communities with conservation, restoration, or resource management have the potential to inform resource managers about the meanings and attachments to place that community members have. Such participatory meetings would also strengthen rapport and set a tone that demonstrates the desire for co-learning and reciprocal learning.

Learning from a place, not just about a place

Learning about something is to objectify it, which implicitly means to be above it. But learning from it means seeing ways it connects to your own life or a something greater. I love this idea. This approach requires humility, respect, and a mind that is receptive. In Hālau ʻŌhiʻa, we operationalized this approach by learning and practicing a ritual protocol to ask permission to enter a place, whether it is a building, home, or forest. When I recite the Mele Komo, a chant, it acknowledges that I am anticipating learning when I step through a door or across a path. Kekuhi told us, “If you don’t ask permission, you have nothing to learn.”

Before and during our class field trips to meet with people who embody relationship to place on the leeward side of Hawaiʻi Island, we discussed this theme of learning from places and the social-ecological memories they carry. The mission statement of Hui Mālama I Ke Ala ʻŪlili (HuiMAU), a non-profit culturally-based stewardship group in the Hāmākua district, says: “We are committed to re-establishing an ʻŌiwi (Native Hawaiian) presence in Hāmākua Hikina, and envision the ʻāina [usually translated as land, but can also mean sea—literally, “that which feeds”] of Hāmākua Hikina restored as places of abundance, where kamaʻāina [children of the land, native born people] are healed by the spiritual forces, sustained by the natural and cultural resources, and elevated to higher levels of consciousness by the ancestral knowledge of these (HuiMAU).

We can also learn from our “plant people” and our “animal people” (Kekuhi’s affectionate terms for plants and animals). For example, dryland forest plants dropping their leaves during drought to conserve energy and water are seen as a lesson for people to adapt to a drying climate, something I heard from a cultural-ecology restoration specialist in North Kona years ago. In Kawaihae (North Kona District of Hawaiʻi Island), Hālau ʻŌhiʻa visited Nā Kālai Waʻa and listened to Uncle Sonny Bertelmann (Pwo navigator and captain of the traditional Polynesian sailing vessel, Makaliʻi) convey the story of his teacher, Papa Mau Piailug, who told him about how people learned navigation from migratory animals—whales and birds. Kekuhi explained to us that when the koholā (humpback whale) expel mucus and water through their blowholes as they move across a seascape, they are helping us remember and tell stories that connect us to Oceania more broadly. Her teenage daughters performed a hula composed by her husband at the cliff’s edge that drove home this message at a deeper consciousness level, beyond language.

Relationships to place are strengthened when you know the names and the stories of the landscape and the beings that inhabit them. As Hālau ʻŌhiʻa, we approached this through kaʻao (described above), learning place names and the stories behind them, as well as spending time engaging the land through stewardship in each place we visited. Although it was gratifying to see how our sweat equity transformed places, Kekuhi reminded us that it’s not how many weeds we remove, or how many plants we plant, that is appreciated; what is most important is what we learn and how we understand our time and purpose in the place at that time. Stated simply: it’s all about relationships.

Reflecting on potential applications in urban areas, the idea of learning from a place underscores the importance of place-based research, embedded knowledge, fieldwork, and the importance of researchers and mangers really “being in” and “connecting to” place. A ritualized “entry” into the field or learning environment (natural area, meeting, workshop, etc.) to set the tone for learning from a place could be done in any setting, including NYC. The protocol itself could be created by or adapted for each project or team, based on their values and experiences. It could even be a silent expression of intention or reflection by the group.

Through my work in NYC, I have heard an appreciation for these ways of learning. Richie Cabo, Director of the Citywide Nursery of the Division of Forestry, Horticulture, and Natural Resources in New York City, shared with me, “We are so much like trees that we don’t realize…we have a lot to learn from these guys.” Perhaps the way forward is to encourage and publicly describe the value of these ways of learning in a professional context. I expect they would resonate with the broader public as well. In all cases, being able to learn from a place is enhanced when one is an informed observer who is attuned to place, reminding us of the importance of building relationships.

Learning the songs, stories, plants, and animals of a place from the local perspective can be a way for resource managers to connect with people and place. In some cases, these can be humbling experiences, demonstrating that local people (including non-scientists) are experts with lessons to teach to managers and researchers. These other ways of knowing are important for resource managers because they inform praxis. But, what about cases when the history or the songs of a place are not known? Or the people who hold that information are unknown to the managers? Can these be created together by people today who are not ancestrally tied to that place? Can a group’s history or mission statement be seen as this type of story? Can the process of knowing a place’s kaʻao foster place attachment (aloha ʻāina, love of the land) for resource managers themselves? Given the cultural heterogeneity of New York City, kaʻao associated with a place or a place-based community present or past can be numerous and layered. Deciding which ones to focus on should be a collaborative process—or, in some cases, there could be room for all of them, in the spirit of work that is place-based, but not place-bound, to borrow a phrase from my colleague Lindsay Campbell.

The process always needs to be localized, project-based, and place-based. To help guide the process, each project needs to think about its goals. In Hawaiʻi, they may be to foster and maintain cultural practices and traditional ecological knowledge associated with those practices in order to support natural-cultural resource management. In other places, such as NYC, it may be to support ecosystem functions while also allowing multiple cultures and user-groups equal access to and sense of ownership over green (and blue) space.

Function over form. Focus on the living practice, not particular objects

Discussions of native verses non-native species can be polarizing, but the idea that natives = good and non-natives = bad is an oversimplification. Instead, the concept of functional ecology allows the integration or acceptance of species that are not native to the area, yet are valuable because of the roles they play in maintaining ecosystem functions. I see this idea akin to what follows.

Because of the inextricable links among people and place, the stewardship of natural resources must also steward the practices, stories, and meanings people have for those places. The future of a particular landscape may depend on the stories, practices, and meanings we share with each other. Yet, we need not get hung up on which ones are the “authentic” or “right” ones. Cultures, like ecosystems, are dynamic. Just because their components change over time does not necessarily mean they are less valuable or inauthentic. The importance of maintaining the living practice so it can continue to adapt and evolve rather than “preserving” any particular cultural artifact or aspect of traditional knowledge is a theme I heard during my time in Hālau ʻŌhiʻa, one that echoed what I had learned previously through my place-based research in North Kona, Hawaiʻi. In the words of systems thinking, flexibility promotes resilience. During our cultural immersion weekend, one of the sites we visited was the ancient residence of Lonoikamakahiki, a prominent ruling chief of Hawaiʻi. Some of this stacked stone structure remains, but it has partially been built over by a tennis court and pool, and it is surrounded by vacation condos.

With reverence, we quietly weeded around the site and removed tennis balls that littered the sacred space. Later in our discussion, one of the participants talked about how unsettling it was to see the site disrespected by the developers and even by those staying at the condos, some of whom just stared at us from their balconies as we mālama-ed (cared for, steward-ed) the ancient residence of Lonoikamakahiki and then chanted together to the kai (ocean). Kekuhi commented that the condition of the residence and adjacent heiau (temple) (which are not reconstructed) is not the most important thing. The important thing is that the practices, relationships, and memories associated with the place live on. More than once, I heard her say that knowledge isn’t lost. People haven’t forgotten, they just need to be reminded, an expression that echoed what I have heard in my place-based research in North Kona, where one woman explained, “We have our characteristics and our system to show what this land has. We’re not lost. It’s not forgotten. The ground still has it. The castor oil plants come back, the ground hasn’t forgotten. We’ll see the younger generations coming back to produce this system with the knowledge they’ve had.” At Ko‘a Holomoana, the navigational heiau (temple, sacred structure) cared for by Nā Kālai Wa‘a (a non-profit organization founded on promoting traditional Polynesian voyaging), it continues to be a source of knowledge and inspiration, even though there is uncertainty about the original meanings of the pōhaku (stones) and their placement.

The deep memories are still there. The place still serves its function. People still engage in a reciprocal relationship with the place, even as the land is up for sale now. Hearing that the land under this incredibly important cultural site is for sale made me think about the vulnerability of places in Hawai‘i (and other places, including urban ones), and how the greatest threat is the ignorance (not knowing, or maybe not remembering) associated with real estate development. This threat is also linked to seeing the land as a commodity rather than kin. It raises the question, how can inevitable change (including real estate development) at the landscape level honor people-place relationships and our ongoing need to connect to nature and to each other in generations past, present, and future?

During our time together as Hālau ʻŌhiʻa, I took note of and came to a deeper understanding of multiple ways of remembering: through listening to and perpetuating the mo‘olelo (histories) of wahi pana (storied places); through stories and teachings from kūpuna (elders) of one’s own ‘ohana (family) or from another ‘ohana or even from another island nation (as was the case with Papa Mau Piailug of Satawal, Micronesia, teaching the first pwo navigators of Hawai‘i); from observing the behavior of plants and animals; and from observing and listening to our children, who can remind us of the magic in the world and inspire us to live pono (righteous) and with reverence for the wonder that surrounds us. All of these ways of remembering help connect us to place and to each other.

In the context of NYC, these themes of continuing practices (without getting fixated on the details of the authenticity of the cultural objects or species, which are certain to transform over time and across the space of migration, land use change, and ecological succession), and of the threats related to “forgetting” and to real estate development, are certainly relevant. Erika Svendsen suggested to me that perhaps some New Yorkers just need to be reminded and inspired to connect or reconnect to places in their own way. She and Lindsay Campbell have written about how people make urban spaces sacred. If feeling connected comes from admiring the arch of a bridge or a river of yellow taxis as much as admiring an upland forest or coastal salt marsh, we can appreciate all the relationships we have with our landscape on a deeper level. Through our own research at the New York City Urban Field Station, we have documented how New Yorkers engage with nature through ritualized practices that connect them to place and support social-emotional-spiritual well-being.

We’ve been working on bringing the social, cultural, and spiritual values associated with urban nature to the forefront (Svendsen et al., in press) so they can be considered on equal ground with other ecosystem services such as provisioning, regulating, and supporting services. Although I have a heightened awareness for why lessons from Hawai‘i could be applied in urban areas like NYC, there are many conversations to have and details to work out. Here I propose questions to consider in initiating conversations as we take the next steps in this journey:

- How can we, as researchers, managers, and policymakers, recognize and embrace the sacred nature of stewardship in our urban work?

- How can resource managers understand human engagement with the environment, including acts of stewardship and the values people hold for a place, as part of the critical functions of a place?

- How can urban resource managers consider the cultural and psycho-social-spiritual aspects of a social-ecological system on par with native species conservation, native habitat protection, erosion control, clean air, and clean water?

- Can these be incorporated into goals for urban green spaces and natural areas?

- How might they be assessed and monitored over time?

Inviting and allowing time for discussing those questions could also be part of conversations about how personal, professional, and spiritual development have intersected or might be integrated in the future. There are prominent conservationists, other scientists, and philosophers who have written about this topic—including a recent TNOC post, Ecology of One—and these writings could be shared as a neutral (non-personal) way to introduce the topic. Through my experiences with Hālau ʻŌhiʻa, I have seen how these kinds of discussions can strengthen our appreciation for and commitment to stewarding place. Ways to introduce this might start with one person sharing their own experiences and perspectives at the beginning of a regular team meeting or devoting a half-day workshop to the topic.

Far beyond my own personal reflections, others are recognizing the potential of amplifying stewardship lessons from Hawaiʻi. The Hawaiʻi Commitments from the IUCN describes “Aloha ʻĀina” as an “inherent part of the traditions and customs of Native Hawaiians” that “embodies the mutual respect for one another and a commitment of service to the natural world.” The document also highlights three critical issues: the nexus between biological and cultural diversity and the role of traditional knowledge, the significance of the ocean for conservation and sustainability, and threats to biodiversity. The document concludes that “Embodying Aloha ʻĀina globally will help address the tremendous environmental challenges we face.”

The themes of environmental kinship and interconnectedness resonate throughout our experiences as human beings, from urban to rural landscapes, from temperate to tropical climates. Refocusing our attention in those areas has great promise to help us navigate our life on island earth.

Heather McMillen

Honolulu & New York City

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the U.S. Forest service for supporting both this training opportunity and my time participating in it. I owe a depth of gratitude to Kekuhi Kealiikanakaoleohaililani for shining the light and teaching the course. Thank you to my NYC colleagues, Erika Svendsen and Lindsay Campbell, who supported my participation in the course, encouraged me to write this, and provided valuable comments. Thank you to Christian Giardina, Kainana Francisco, Claire Gearen, Laura Booth, and David Maddox for providing valuable comments and suggestions. Thank you to my fellow participants in Hālau ʻŌhiʻa who enlightened me and also provided some of the photographs in the blog. Thank you to my friends and family who helped care for my son, Eli, while I traveled to participate in the training and thank you to Eli for the ongoing creation and inspiration.

Reference cited

Svendsen, E., Campbell, L, and H. McMillen. Stories, Shrines, and Symbols: Locating well-being and spiritual meaning in urban parks and natural areas. Journal of Ethnobiology, special issue on urban ethnobiology. (Scheduled for October 2016)

Add a Comment

Join our conversation