In the science of natural resource management and planning, we often think about land from a “bird’s-eye” view: parcels on a map that delineate parks, residential properties, and the city streets—for example. Understanding these sites from a “worm’s-eye” view presents a different, more grounded experience of space and place.

In particular, boundary lines clearly delineated on parcel maps may become blurrier when viewed in person. The edge often serves as a porous space of interface and exchange, but it also can be a site of exclusion or division. The ebbs and flows of people moving through these boundaries become visible; the mimicry in forms across land uses and ownership can be observed; and we can detect signs of stewardship, attachment, and expressions of identity. Qualitative methods in social science can open up this grounded experience of place to provide insights about the uses and meanings of urban parkland, which in turn can inform our design and management strategies.

Social assessment of park use

Since 2013, an interdisciplinary team of scientists and natural resource managers at the New York City Urban Field Station and the Natural Areas Conservancy have been undertaking a study to investigate the social dimensions and value of public green space in New York City. This study, a Citywide Social Assessment of New York City Parks and Natural Areas, explored approximately 9,000 acres of New York City parks in an effort to better understand the social meaning of these green spaces. Adrian Benepe previously reflected upon the findings of the 2013 social assessment in a May 2015 TNOC post.

With this portion of the study, we sought to understand: what are the spatial patterns of human park use? We paid particular attention to boundary dynamics at the edge interface between the park and the community, developing a different methodology and protocol for treating the edge. We defined the edge as the area directly adjacent to, but outside, the park boundary. The protocol guided qualitative observation through field notes and photo-documentation of the streetscape and properties adjacent to parks. Unlike the rest of the social assessment, research crews did not conduct interviews on the edge, but took detailed notes of all encounters with individuals who voluntarily approached them to speak.

Porosity: visual and physical access and openness

Across different parks and within each park, we observed large variations in park edges in terms of their porosity: some edges were very clearly marked, with fences or other physical barriers distinguishing between the park and the surrounding neighborhood (Figure 1) while other edges were less distinct (2). Along one of the fenceless edges of Conference House Park in Staten Island, we also observed signs of a bench in the shade of a tree creating an intentional viewshed from a private lawn to the public park (Figure 2).

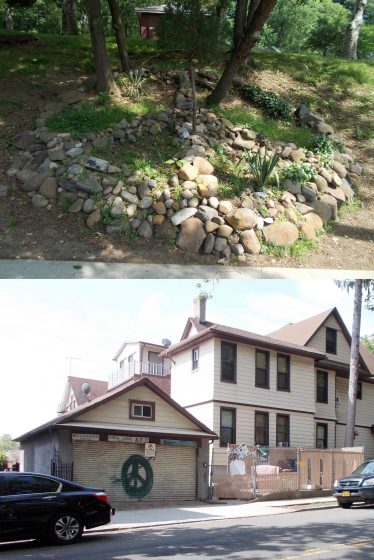

Blurred boundaries: overlapping territories

Occasionally, it was difficult to distinguish between the park and the surrounding neighborhood. For example, in Clove Lakes Park in Staten Island, we saw a small informal garden (Figure 3a) on what appeared to be NYC Parks’ property according to our maps, but also happened to be on the other side of a house at the end of the dead end road. Near Conference House Park, we saw a very large deck that appeared to extend to the edge of NYC Parks’ property, if not onto the park itself (Figure 3b). The deck was around 3 to 4 car lengths, so both its size and its location were unusual.

Many parks are also directly adjacent to private backyards, and we observed different ways that residents had made the park an extension of their backyards. For example, at Clove Lakes Park, we saw a backyard with a row of shrubs planted to distinguish between private property and NYC Parks property, but there was an intentional mowed and unplanted gap between the backyard and the park, allowing for physical access between the spaces (Figure 3c). At Brookville Park in Queens, we saw informal vegetable and herb gardens along chain-linked fences that separated an owner’s property from the park (Figure 3d). We observed that these were likely maintained by a resident or multiple residents, as there was an open gate in the chain-linked fence, and there was often a pile of gardening supplies near that gate.

In simple terms, these overlapping territories can be seen as positive (engagement, stewardship, ownership, and attachment) or negative (encroachment, privatization of public space). Instances of blurred boundaries between park and home should be further investigated in order to understand how urban residents form attachment and meaning to parks and natural areas. At the same time, what may appear as encroachment or privatization may actually stem from the need to create a safe and viable space, suggesting that these types of activities are a form of stewardship and civic engagement.

Mimicry: shared sense of ownership and identity

At Forest Park in Queens, we saw signs of landscaping on the park edge that mirrored the neighborhood side directly across the street and was not found in any other part of the park or other parks (Figure 4). It was unclear whether this landscaping was performed by NYC Parks workers or the community; nonetheless, it is notable that time and effort was invested into creating a sign that linked the park to the neighborhood. We see these acts of mimicry as subtle signs of shared ownership and identity through care and design.

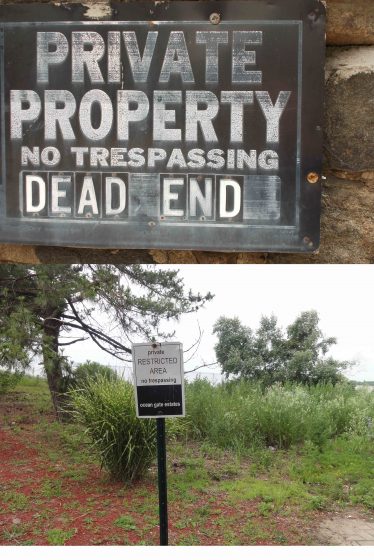

Exclusion: boundary marking and contested meanings

While some signs showed integration between the neighborhood and the park, we also observed signs of a desire to erect clear boundaries between the neighborhood and the park. At the edges of Brant Point Wildlife Sanctuary and Dubos Point Wildlife Sanctuary, residents installed fences along with “Private Property: No Trespassing” signs to clearly mark the border between public and private land (Figure 5). Similar signs were also posted near Alley Pond Park in Queens and Wolfe’s Pond Park in Staten Island (Figure 6).

Portions of Brookville/Idlewild Park in Queens are very wet and marshy. Numerous residential street- ends adjacent to the park occasionally flood in heavy rains. We interviewed one neighbor who told us about her work in stewarding this edge of the park. Her family had collected money to remove storm debris after Hurricane Sandy, out of concerns over aesthetics and the potential for mosquitoes to breed, which could be vectors for West Nile virus. She had made requests to her NYC Parks Borough Forester related to nuisance trees. At the same time, she was maintaining a small, manicured garden, directly on the edge of the park, saying, “This is mine, I claim it!” Clearly, these neighbors feel a strong attachment to this edge garden, though they do not venture into the wetlands beyond the edge.

Overall, park edges can convey information about the surrounding neighborhood’s attitudes towards their own private property in relation to the park. While some residents appear to welcome the blurry boundaries between the park and the neighborhood, other residents feel the desire to make those boundaries explicit and marked, through signage and through stewardship practices.

Re-designing the edge: Parks Without Borders

In policy and planning circles, there has been a recent acknowledgement of the importance of the park edge. The City of New York launched a new program in 2015 titled Parks Without Borders to improve the entrances, accessibility, site lines, and edges of New York City parks (NYC Parks 2016). Drawing upon extensive community input and voting, NYC Parks selected eight showcase parks across the five boroughs of New York City to receive a new design treatment of their edges that will create a more seamless public realm between the park, the sidewalk, and the street. This effort is informed by NYC Parks Commissioner Mitchell Silver’s background as an urban planner and as a former president of the American Planning Association. Silver presents this initiative as good planning and design put into practice.

In a dense city of 8.5 million people, the square footage to be gained from a redesign of the park edge and its interface with the public right of way is not an insignificant amount of open space. While the eight showcase parks will receive the most extensive design treatment, NYC Parks is already implementing these design strategies into new capital investments whenever possible.

One underexplored area to investigate and consider is how the edge of natural areas—woods, meadows, and wetlands—can be designed to invite use, exploration, and stewardship while still providing valuable habitat to many species, including rare and sensitive ones. Certainly, different strategies will be required for natural areas abutting recreational parkland, open water, private property, and public streets—but all of these present opportunities for thoughtful trail design, wayfinding, entrance points, public art, and interpretation.

The worm’s eye view is the view of the park user, of the street ethnographer, and of the section drawing in an urban design. It is crucial to bear in mind as we make decisions about how to design, manage, and program our edges and interiors. The edge is an interstitial space between public and private realms that can draw us toward or away from our parks and natural areas.

Lindsay Campbell, Novem Auyeung, Michelle Johnson, Erika Svendsen

New York City

about the writer

Novem Auyeung

Novem Auyeung is a Senior Scientist, Division of Forestry Horticulture & Natural Resources, NYC Parks. Novem guides conservation, research, and monitoring priorities for the Division.

about the writer

Michelle Johnson

Michelle Johnson is a research ecologist with the USDA Forest Service at the NYC Urban Field Station.

about the writer

Erika Svendsen

Dr. Erika Svendsen is a social scientist with the U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station and is based in New York City. Erika studies environmental stewardship and issues related to hybrid governance, collective resilience and human well-being.

Thanks to those that choose to integrate the park into their space vs. marking the boundary with a wall or fences. When the above is possible, then many more can enjoy the space.