about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David's dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to "fall back on". So he bought a tuba.

Introduction

Letting go of some of the domestication of our cities might be a hard sell to a mayor. It sounds a little like chaos—like we’re going to stop mowing the grass in the park. But the idea of urban re-wilding started out as a movement to restore some “real” nature to cities, in the form of (relatively) undesigned and unmanaged spaces: space in which nature can be nature. There are potentially biodiversity conservation reasons to pursue re-wilding, but there are also some compelling reasons to do so in the realm of human health and wellness.

So, you get your meeting with the mayor, and she or he is skeptical. What do you say to convince them, both about the cost and the benefits, and how you would go about accomplishing the re-wilding? The mayor is busy and up for re-election: you have 800 words-worth of their time.

Does re-wilding make better cities, or just wilder ones? Explain it to your mayor: why should she or he care about re-wilding? Here are 16 contributions. Perhaps they will provide some inspiration for the next time you find yourself in an elevator with the mayor, or over coffee at a reception.

about the writer

Keith Bowers

For nearly 30 years, Keith Bowers has been at the forefront of applied ecology, land conservation and ecological restoration. As the founder and president of Biohabitats, Keith has built a multidisciplinary organization focused on regenerative design.

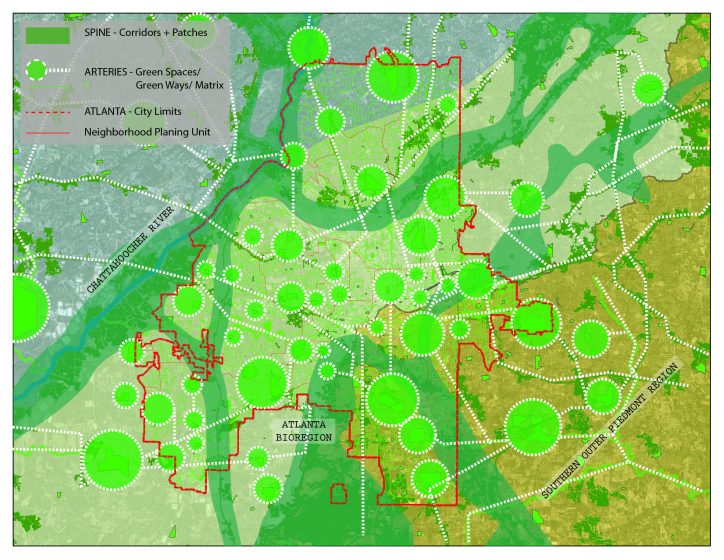

Keith Bowers, Charleston

Yes, of course re-wilding makes for better cities. In fact, mayors should not only embrace re-wilding as part of a culturally rich, socially just and economically robust future for their city, they should also be the primary supporters for re-wilding the countryside.

No, we are not talking about re-wilding Pleistocene era wooly mammoths, but in my mind, we are talking about restoring natural landscape level ecological processes; providing habitat corridors and patches for native flora and fauna; and reintroducing apex predators and keystone species which play a critical role in maintaining the structure of an ecological community.

Protecting and restoring natural ecological processes provides a host of benefits that we often take for granted, including access to clean air, fresh water and healthy soils; carbon sequestration and storage, moderation of extreme events, erosion prevention and flood attenuation, along with habitat for native plants, birds, fish, mammals and insects. All are critical for maintaining the biological health of our ecosystems.

Many cities struggle to implement costly and often ineffective strategies to mitigate the loss of these naturally occurring ecological services. Sustainability plans begin to chip away at these issues, but they are often divorced from the underlying causes that gave rise to many of these problems—a disassociation with the natural world. We have found that embracing and weaving the concept of re-wilding into the fabric of cities can result in a more livable, just, healthy and resilient place.

That said, realizing the vision of re-wilding means breaking down traditional paradigms of how we think about cities, public spaces, and aesthetics. How do we go about re-wilding from a practical standpoint? Our recent work in cities like Baltimore, New York City, Cleveland, San Francisco, Kansas City, and now Atlanta, has underscored the importance of thinking about re-wilding based on three interlaced themes:

- First, we believe that re-wilding needs to be grounded in sound science, yet fully embracing the intangible qualities that make each city unique, that give it its sense of place, that celebrates its genus loci!

- Next, we have found that effective re-wilding needs to encompass a tapestry of richly layered and intricately connected systems of green spaces, greenways, and natural features, at nested scales, interwoven throughout the fabric of the city.

- Finally, re-wilding within cities should address environmental justice issues, ensure that every neighborhood in the city has free and unencumbered access to quality green space, and guarantee that decisions regarding city governance are accomplished through an inclusive, transparent, just and participatory process.

Re-wilding cities can surely address a host of environmental, social and economic issues that mayors would be envious of. But is it enough? No.

First, all cities are highly dependent on the extraction, production, flow, and disposal of goods and services from surrounding regions. This ecological footprint typically encompasses areas of land much larger than the city itself. If a city is truly striving to be sustainable and resilient, then it must consider its full array of long term needs and impacts. Re-wilding can therefore be a wonderful and effective way for mayors to offset their ecological footprint, meet sustainability goals and create a more resilient city.

Second, unlike attempting to re-wild within cities, re-wilding regional landscapes affords the opportunity to reconnect large expanses of fragmented habitat, restore key ecological processes and provide exciting possibilities for reintroducing predators, keystone species and a full array of biological diversity not attainable in cities. Interwoven within a matrix of small towns, farms, transportation corridors and industry, re-wilded landscapes can assure that cities have access to the ecological services and biological diversity that are vital to their long-term health and well-being.

Now, imagine if a string of cities along North America’s east coast began initiating re-wilding efforts within their respective cities. Then, imagine if the same string of cities forged an alliance to help fund a continental re-wilding effort, from maritime Canada to the subtropical Everglades of Florida. The power of these combined efforts would exponentially ensure each cities access to clean air, fresh water and productive soils. It would provide cities with more tools to mitigate climate change and withstand disturbance regimes, and it would boast long-term biological capacity to provide pollination, assimilate wastes, and recycle vital nutrients.

Wooly mammoths and saber-toothed tigers aside, cities now have a real opportunity to embrace re-wilding as a means for a more culturally rich, socially just and economically robust future.

about the writer

Louise Lezy-Bruno

Louise is Deputy Director of the Environment in the Paris Region. An Architect-Urban Planner with a PhD in Geography, she works on the cities-nature relationship. She is a member of the IUCN-WCPA.

Louise Lezy-Bruno, Paris

In 2016, France, and the Paris region in particular, were hit by severe floods. These events made an impression on everyone. They caused contradictory reactions on the results of re-wilding cities:

- Conservation policies of natural areas, especially marshes and wetlands along the rivers, have borne fruit. These protected natural areas played their buffer role for flooding storage.

- Following these flood events, with the receding floodwaters, human-wildlife conflicts increased. The animals spread out, some displaced by the rising waters, others harmful, carriers of disease: mosquitoes, rats, foxes, wild boars.

Regarding the first point, the reactions were very positive on the mitigation role of the natural areas for relieving the flood effects. This confirms the political choices made according to the virtues of nature-based solutions for urban planning. However, the second point reminds that nature can also be perceived as a nuisance.

Urban people recognize the benefits of nature and their desire for wilderness. Yet, they want a sanitized nature without any inconvenience. They dream of an “urban nature”, in the primary sense of the word “urban”: civilized and polished.

Nature conservation specialists thought it was possible to strengthen biodiversity conservation by “naturalizing” cities[i]. But will we succeed in combining nature in the city with the old medieval fear of the wolf? If we can provide answers to this question, we can convince the mayor and other elected officials to progress on re-wilding the city.

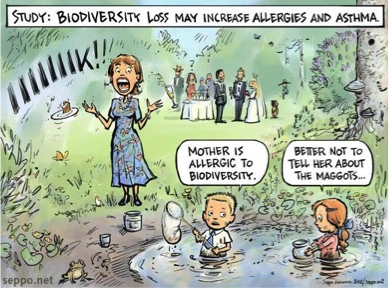

According to the mayor, the usual talk about the benefits of nature in the city is something for professionals. It would even be well integrated by them—architects, urban planners, developers, elected officials. All know the arguments that nature provides a lot of benefits for the city: air quality improvement and reduction of pollution; allergy prevention, asthma reduction and increased immunity; regulation of air temperature and reduction of the urban heat island effect; improved soil quality, regulation of the water cycle, risk reduction, reduced energy use, carbon sequestration.

However, for the citizens, urban biodiversity is the spider that invades their home, the knots of mosquitoes at the lake edge and other mosquito breeding sites, and the wild boars that plow their gardens.

The mayor asks for another speech about nature in the city, new and innovative, of course. For him, the discourse about a functional nature is for professionals. He wants to stand out from his predecessors and to win the support of the voices that count, that of the citizens.

Through the discourse on climate change and loss of biodiversity, the increased pollution, the development of respiratory diseases, the increase of the flood and drought extreme phenomena, citizens have begun to realize the importance of preserving nature in a holistic way.

But what interests the mayor is making his fellow citizens understand the importance of starting with their own garden, their street, their city. It is a matter of demonstrating in practice that when a street tree or a park helps to cool the weather during periods of significant heat waves, people understand that nature in the city does not have only aesthetic virtues.

Whether only a global policy comprising a coherent and balanced package of multiple measures is likely to bear fruit, the path for re-wilding the city must pass through a re-wilding urban people.

For touching the human being, we must explore the symbolic and sensorial values of nature. This is about the guy, in Rio, who goes to the beach at the end of the day just to enjoy the sunset or swim in the sea. The same call of the wild moves the Capetonians to start their day with a mountain bike tour of Table Mountain. A simple walk in a park or public garden in any city in the world is surely less exceptional, but equally relaxing.

What are these urban people looking for? According to Dr. Nooshin Razani, “Within five minutes in the trees, our heart rate goes down and within 10 minutes our brain re-sets our attention span”[ii]. In our hyper connected world, the perception of nature as a haven of peace and calm is extremely important for peoples’ physical and mental health and well-being.

For citizens to be wild again, we must recreate their natural roots, to make them actors of re-wilding cities. Gardening in the city is a way of reconnecting urban people to nature and recreating social links. People can participate on re-wilding public spaces (green a sidewalk, cultivate a community garden) and also their private space to make backyards biodiversity friendly (without agrochemicals, with native species, with using rainwater, etc.).

From the movement to conserve, restore, and reconnect natural areas, the idea of re-wilding cities must be expanded to how to relink humans with nature. The objective now is to spread the word that beyond biodiversity conservation and aesthetic benefits, re-wilding cities provides free recreational areas and improves physical and mental well-being. Nature in the city also offers spiritual values, without forgetting its economic benefits of lower energy costs and increased property values. This is a speech that urban people understand.

According to David Goode, speaking about London, the main lesson we can learn from urban ecology actions is that “gaining local commitment and support was crucial to success”[iii].

This means that the key to success in re-wilding cities is not politics but people.

Notes:

[i] Michael L. Rosenzweig, Win-Win Ecology : How the Earth’s Species Can Survive in the Midst of Human Enterprise, Oxford University Press, 2003.

[ii] https://baynature.org/article/brain-nature-healthy/

[iii] https://www.thenatureofcities.com/2017/10/15/can-learn-past-successes/

about the writer

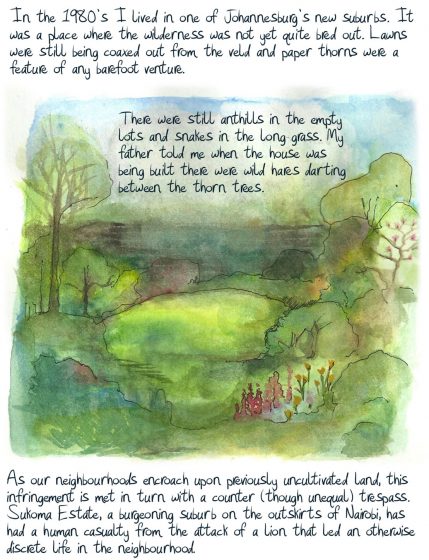

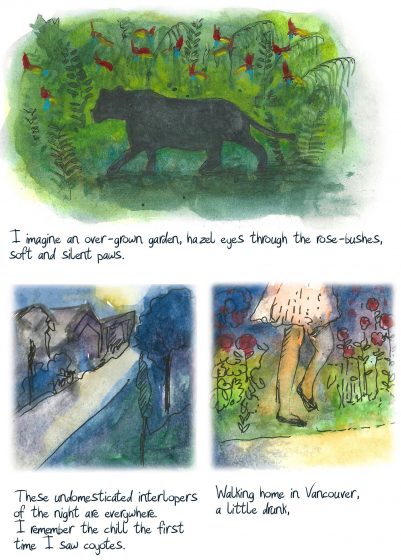

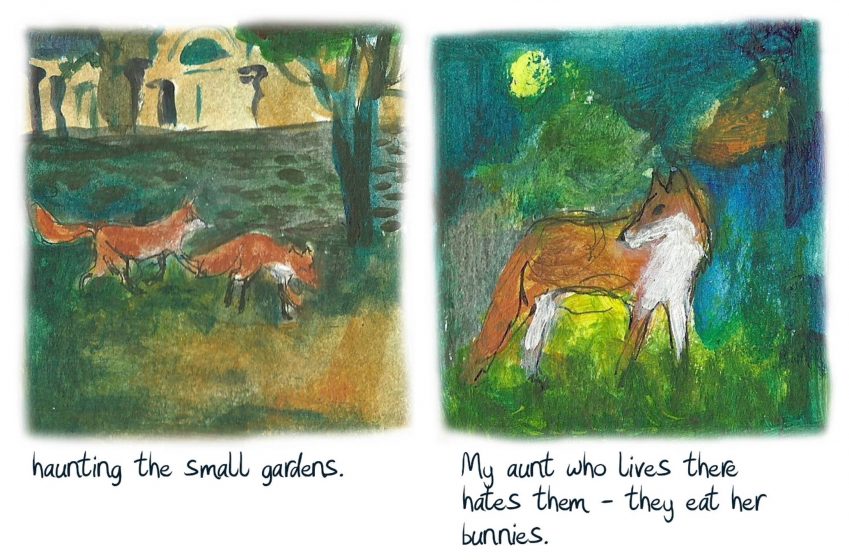

Katrine Claassens

Katrine Claassens' paintings reflect her interest in climate change, urban ecology, and internet memes. She also works as a science, policy and climate change communicator for universities, think tanks, and governments in South Africa and Canada.

Katrine Claassens, Montréal

A longer version of this story can be seen here.

about the writer

Don Dearborn

Don Dearborn is a professor in the Biology Department at Bates College in Maine, USA, where he teaches and studies evolution and ecology.

Don Dearborn, Lewiston

The affluent can always buy wilderness access. What about everyone else?

Let’s flip the question for a moment. Instead of “Why wilderness?” let’s ask “Why cities?” Economists would say that cities are efficient places to live and work, if you’re not a hunter-gatherer or a subsistence farmer. Cities offer shared infrastructure, economies of scale, facilitation of trade, facilitation of consumption. In that sort of modern economy, people’s jobs are removed from nature. Our entire lives are removed from nature. We have more money than time, so we buy food instead of farming or hunting, buy water instead of living near water, buy petroleum-based heat to stay warm at the flip of a switch, buy electricity to make our lives more convenient, buy special soap for our time-saving dishwashers. But despite these urban conveniences, we still feel the allure of wild places, and thus the more affluent among us buy access to nature the way we buy everything else. We buy it with the purchase price and the taxes on homes in affluent neighborhoods adjoining nature reserves, and we buy it with weekend getaways to the wilderness outside of town.

If cities are so great, why do we spend this money for access to wild places? Because wild places speak to us in profound and intimate ways that stretch back into our personal and evolutionary pasts, when we were inextricably connected with the land. As an affluent person who works in a city, I drafted part of this letter while visiting a quiet, empty lake in the Maine mountains (USA), two or three weeks after the peak of autumn foliage. I felt like I had stepped into another world, far from my normal routines and the stress of work and life in a small city. My sense of realignment was partly because of the physical distance from the things that drain my attention and energy on a daily basis. But a more powerful contributor to my realignment was the simple wildness of the place. In nature—but not so much in groomed parks—there is silence, and there are surprises. There are mysteries. Crayfish waiting patiently beneath stream-bottom rocks. Salamanders under wet, rotten logs. Plants in perpetual slow-motion battles for access to sunlight. Animal noises that defy easy identification. These things demand us to be present in the landscape, in the moment, in a way that is restorative.

Research demonstrates the impact of wild places on human health. I’ll ignore here all the clear financial benefits that urban nature can provide via ecosystem services—pollination, stormwater control, reduced heating and cooling costs, and more. Such benefits are compelling and surprising in their scale, but here I want to focus on the most direct impacts on humans. To wit, a healthcare study showed faster recovery from surgery for patients whose hospital windows overlooked trees rather than a brick wall. Others have shown that access to nature—even urban nature—reduces mental fatigue and helps people see their problems as more manageable. Forests improve air quality, which leads to better respiratory health. (A recent study suggests that one in six deaths, globally, are connected to pollution. One in six!)

Developmentally, wild places provide kids with crucial opportunities beyond what they get on an iPad or a football field. Kids need unstructured play, especially in wild places that connect them with nature—places that demand agency and creativity, that teach them to judge and manage risk; places without a cushioned landing on shredded tires. Agency, creativity, and risk assessment typify successful leaders in business and in society. And even if not leaders, we need these future-grownups to become good stewards of our planet, which will hinge on the extent to which they connect to the natural world as kids.

People in power are disproportionately affluent, and if politicians decide that cities don’t need or deserve wild places, those same power brokers will still have their weekend getaways to the mountains, the coast, the lake. Urban re-wilding can help provide equal access, because it can be accomplished inexpensively and locally to all neighborhoods. Untamed wild spaces are cheaper to create than manicured parks with fancy facilities and groomed lawns and seasonal flower beds, and they have no maintenance costs. If you don’t need these spaces to be part of the maintenance circuit of your landscaping crew, they don’t need to be centrally located. This flexibility, combined with the low establishment cost, makes it cost-effective to create wild spaces all over the city, to provide local access to everyone. And it doesn’t take pristine starting material—you can allow wild growth on abandoned lots and brownfield sites, and let nature take its course. Cities are economically inevitable, but the idea that urban wild places and the economy are incompatible is an argument put forward by people who will have access to wild places regardless of how accessible those places are.

The less affluent will have no such luxury. Bring nature to the people.

about the writer

Ian Douglas

Ian is Emeritus Professor at the University of Manchester. His works take an integrated of urban ecology and environment. He is lead editor of the "Routledge Handbook of Urban Ecology" and has produced a textbook, "Urban Ecology: an Introduction", with Philip James.

Ian Douglas, Manchester

In absolute contrast to the practice of re-wilding as adopted in remote wilderness areas far from major human settlements, re-wilding in urban areas means removing the influence of the dominant organisms in the urban ecosystem: people. Urban areas are clearly the localities where human beings have most modified the work of natural processes and have most altered climate, hydrology, terrain, vegetation and animal populations. Urban re-wilding is the process of removing human intervention from patches of ground and allowing nature to proceed to colonise and occupy such areas without further human interference. Sometimes such processes happen deliberately, as when a former mine waste tip of abandoned factory site is left unused and gains some protection as a part of a peri-urban country park or “wilderness”. (In Manchester, there is a derelict sewage treatment plant that has become totally re-vegetated and remains undisturbed because it is securely fenced). At other times the processes follow drastic human action. I am old enough to remember the recolonization of bombed areas of the City of London, England, after the Second World War. Similar re-wilding is probably happening now in the destroyed cities of Syria and Iraq.

I used to tell students in my lectures on the urban environment that “nature fights back”. In Manchester in the 1990s, I took urban ecologists to Pomona Dock at the inland terminus of the Manchester Ship Canal. Abandoned 20 years previously, the dock wharves had been colonised by multiple invasive plants, from the usual suspects, such as Buddleia, to many rarer species. A few years later all the wild vegetation was cleared. However, redevelopment did not occur. Nature has fought back again and twenty more years on, tree saplings are reappearing among the invasive plants.

However, human beings are introducing species to the urban wild all the time. Feral cats and dogs abound. Exotic pets escape (or are illegally released) within towns and cities. The whole history of plants that escape from gardens and harmful invasive species, such as Japanese knotweed, is well known, but is also an inadvertent contribution to urban “re-wilding”.

However, people seem to wish for a designed, controlled urban re-wilding, with preferences for the presence of certain species: native plants without the invasive species; a diversity of birds, without the escaped parakeets or feral cats. Probably such controlled urban re-wilding is merely a version of the creation of public parks the way the Olmsteds created spaces in New York, Chicago, and Seattle. In Britain, with inadequate expenditure on public services—such as urban parks and environmental protection—re-wilding may be occurring by default, through reduced mowing of grassy areas and general neglect of tree-covered spaces.

For me, whatever happens adds to the interest and fascination of urban ecosystems and makes them interesting for us all, particularly our children and grandchildren, to explore and enjoy. Letting nature take its course is good medicine to help us cope with our urban ills.

Ana Faggi, Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires flourishes in October and November, being the perfect time to visit the city and its green spaces. The brightness of the urban green and the multiple colors of the flowering trees are its main attractions.

A very significant green space is a historic garden: the Rose Garden located in the Tres de Febrero Park. The garden created in 1914, is three hectares (ha) and is a cultural and historical heritage place. This a beautiful place, with about 18,000 rose plants of diverse varieties, is also a tourist attraction (Fig. 1)

In the world, roses are the most preferred flowers. It is that, regardless of their fragrance and beautiful forms, roses are a love symbol. The symbolism comes from ancient times: Greeks and Romans identified their respective goddesses of Love, Aphrodite and Venus with roses.

When the Rose Garden blooms it is filled with people who marvel at the variety: roses of different colors, sizes, shapes, structures, perfumes and names that celebrate princes and princesses, or outstanding personalities. The Rose Garden is one of the most important green areas of Buenos Aires not only for the roses but also for its design that includes, in addition to the beautiful bridge at the entrance, a large pergola also in Greek style, a jetty next to a small lake and a temple. It is an ideal place to walk, to contemplate or take pictures.

But what are the ecosystem services that such a green area provides? Undoubtedly it has a great historical and cultural value. However, the area that requires a lot of landscaping, gardening and maintenance work does not provide habitat for wildlife. There are no insects, and only few birds like doves or sparrows.

A contrasting situation that shows the importance of including re-wilded areas in the middle of the city is the garden at the National Museum of Natural Sciences where I work (Fig. 2). There, about ten years ago, a project of re-wilding a sector of a conventional park was carried out and was consistent with the idea of local conservation. Therefore, in just 0.8 ha, a wild garden was created to show visitors and school children the typical vegetation of the Buenos Aires region. It includes riparian and dry forests, grasslands and a constructed lagoon.

The multiplicity of habitat types favors the diversity of wildlife. More than 150 species of plants that include trees, shrubs, grasses, and epiphytes are the habitat for 36 species of birds and large amount of insects (Fig.3). This small patch of green provides many ecosystem services from support, and regulation to provision in addition to cultural benefits.

The multiplicity of habitat types favors the diversity of wildlife. More than 150 species of plants that include trees, shrubs, grasses, and epiphytes are the habitat for 36 species of birds and large amount of insects (Fig.3). This small patch of green provides many ecosystem services from support, and regulation to provision in addition to cultural benefits.

It is a garden that shows that once the local vegetation is installed, the associated fauna—that one believes absent—returns to the city. It is also a good example of an urban green area that does not need maintenance or special care. No need to water, no insects are fought or chemical additives are used. It is a resilient place where all is in balance, everything is recycled; and it is the best justification to the mayor of the city as to why he should care about launching projects like this to increase native natural assets in the city.

The re-wilded garden might be mysterious to many visitors. As the city sprawl and the natural landscape disappeared, people lost contact with the natural, pristine vegetation of the city where they live. The garden allows people to know the local flora.

The leafy forest, the crunching of branches and the sounds of nocturnal insects are also a perfect setting every October to celebrate Halloween. The little garden becomes a “mysterious forest” as witches to the cry of Samhain receive many children in costume (Fig.4).

about the writer

Lincoln Garland

Lincoln is Associate Director at Biodiversity by Design, an environmental consultancy in the UK. Lincoln has been working as an ecologist and eco-urbanist in consultancy, academia and for wildlife NGOs for more than 25 years. He has a particular interest in developing sustainable ecologically informed landscape-scale approaches to development and land management, with a particular emphasis on the urban realm and ecotourism. Contact Lincoln by email: [email protected]

Lincoln Garland, Bath

I have been asked to set out here my standpoint on the opportunities for implementing urban re-wilding in my city of Bristol and also other UK cities. Urban re-wilding is an offshoot of the wider re-wilding movement, a relatively new approach to nature conservation that has been rapidly gaining momentum over the last decade.

The UK includes no meaningful areas that approach bona fide wilderness; our landscape is the product of 1000s of years of cultural influences rather than untamed nature. Re-wilding, however, aims to restore to the UK (and elsewhere) large-scale core wilderness areas and dynamic natural ecosystem processes. While some wilderness engineering may initially be required to re-establish apex predators and keystone species, ultimately the aim is to allow the process of natural ecological succession to take its course with no or very limited human-based intervention, as the successful reintroduction of such species is intended to deliver self-regulating ecosystems.

There are certainly opportunities for introducing re-wilding in rural parts of the UK, in particular in upland regions where, without subsidy, agriculture is economically unviable for the most part. With respect to the UK’s cities, nature should also be allowed to take its own path in certain select locations to create some semblance of wildness. I am unconvinced however that re-wilding is the appropriate terminology or the approach to wildlife restoration that we should be pursuing in UK cities at any meaningful scale.

The large expanses of greenspace that would be required to recreate fully functioning wildwood, including relatively large numbers of herbivores and viable populations of naturally scarce predators at the top of food chain, are simply not available in our cities, where space is increasingly at a premium. Sustainable urban design should be seeking to avoid low-density sprawl and instead promote compact, transit-oriented, pedestrian-and-bicycle friendly urban development that provides easy access to services. This development model is crucial for tackling congestion and for reducing CO2 and other harmful emissions. Given this compact city imperative, the proposition of devoting large areas of urban space for re-wilding in anything approaching its true sense is untenable.

The suggestion that brownfield sites could provide the large areas required to implement urban re-wilding is particularly worrisome. While post-industrial landscapes can support a wealth of wildlife and should be preserved for this purpose in a few select locations, they must primarily be set aside for redevelopment as part of sustainable urban densification strategies.

Proponents of urban re-wilding might counter that it is a caricature to imply that they wish to revert to something akin to the Pleistocence epoch, where woolly mammoth and cave lion, brought back from extinction through genetic engineering, freely roam across our cities within vast tracts of newly created forest and grassland. Rather they contend that their vision for urban re-wilding is much more modest in its objectives. Perhaps the UK’s many large urban parks provide alternative, more moderately sized opportunities for re-wilding. Many of these do include large expanses of tightly mown amenity grassland that would seem to provide space for unruly nature to reassert itself, and indeed there are examples of this being encouraged in Bristol’s parks and elsewhere. But even in these greenspaces there are multiple competing interests that significantly limit the scale of possible change.

Some authors/practitioners respond that there should be no minimum area thresholds for wilderness and re-wilding from an ecological perspective, frequently quoting Aldo Leopold who declared that “no tract of land is too small for the wilderness idea”. While it is true that ecosystems can be considered at the microcosm, there really is not the space available to recreate complex self-sustaining food webs, with meaningful ranges of predators and prey, in accordance with the true principles of re-wilding.

Even ignoring the seeming disregard for matters relating to population viability analysis and the principles of island biogeography, other concerns remain. In those small areas where nature can be left to its own devices, many people may have a profound dislike for the outcome that sometimes emerges. Negative comments may be expressed relating to perceptions of safety, the appearance of neglect, reduced accessibility and visual/aesthetic preference. With respect to the last of these concerns, while education programmes can attune people’s valuation patterns, within an urban context a great many people will continue to favour more ordered, manicured environments. Undeniably, a previously accessible urban greenspace that has been left to nature, which then rapidly succeeds into a monoculture of impenetrable bramble or butterfly-bush, is unlikely to be well-received by most local residents.

A woodland brimming with wildlife and resounding with the chorus of birdsong can take far more time for nature to deliver by itself than many people are prepared to wait. Furthermore, the idyllic deciduous woodland scene that most people in the UK probably assume to be wild and natural, is in fact attributable in no small part to human activities dating back 100s and sometimes 1000s of years, including coppicing, clearances and hunter-gathering. Prior to and overlapping with man’s influence, grazing by aurochs (the wild ancestors of cattle), deer and wild boar would have produced large sunlit glade areas and open-structured woodland, which would also be impossible to replicate in an urban context without significant human intervention.

The disturbed nature of urban soils is likely to be another major limiting factor, impoverished as they frequently are in terms of seedbank, organic material and soil organisms. Without active management newly emerging urban woodland would also be subject to degradation by trampling, visual and noise disturbance, fire, invasive species, effects of predatory pets etc. To reiterate, unencumbered natural succession may well produce landscapes in urban areas dramatically less visually and ecologically appealing than anticipated.

Putting these objections to one side, if we are asking a separate question, should we be endeavouring to create an ecologically rich urban realm, including more street trees, urban meadows and copses, perennial borders for pollinators, sustainable drainage systems, restored rivers, living architecture etc., then count me in. As an ecologist and eco-urbanist this is my raison d’être (see Figures 1, 2 and 3). However, suggesting that these practices are somehow novel and then grouping them all under a new urban re-wilding banner, which many appear to be doing, dilutes the concept’s true spirit, potentially rendering it meaningless.

Perhaps in response to the difficulties I have outlined, some authors have suggested that the definition of urban re-wilding be broadened even further, encompassing cultural urban ecosystems, and allowing for repeated interventions to retain early successional stage habitat to benefit particular species. Such interventions may indeed be desirable in many circumstances but should not be conflated with re-wilding. Surely the concept of re-wilding mustn’t be contorted to such an extent that it is all things to all men.

In summary, to casually refer to re-wilding as incorporating the majority of urban habitat restoration practices, undertaken at almost any spatial scale and even including the maintenance of cultural landscapes through ongoing human stewardship, debases the concept. The excessive flexibility being allowed for in defining urban re-wilding would seem to reflect the fact that the opportunities for implementing it in its true form are not generally available in UK cities or indeed within many cities in other parts of the world. The prospects for re-wilding are diminished further by the fact that many cities are progressively prioritising the multiple sustainability benefits associated with compact city living. The absence of true re-wilding in our increasingly densified urban realm should though not concern us per se. With vision and creativity there still remains multiple opportunities for re-wilding in rural areas, and also for integrating and experiencing a rich array of wildlife within the urban environment, all be it in a more managed, and unashamedly ‘designed’ context.

about the writer

Amy Hahs

Dr Amy Hahs is an urban ecologist who is interested in understanding how urban landscapes impact local ecology, and how we can use this information to create better cities and towns for biodiversity and people. She is Director of Urban Ecology in Action, a newly established business working towards the development of green, healthy cities and towns, and the conservation of resilient ecological systems in areas where people live and work.

Amy Hahs, Melbourne

I’d like to invite you to consider this proposition for how you can leave a lasting visible and highly valued legacy in this city and be remembered as a visionary leader by this generation of residents and all those who follow after. This legacy is not embedded in bricks and mortar, sports stadiums, or public buildings, but rather in the infinitely more enduring legacy of landscapes, human wellbeing and sustainable prosperity, delivered through the vehicle of “re-wilding” our city.

The concept is a simple one. Throughout human history, our existence and living conditions have been intertwined with the landscapes in which we live. The natural world can inspire a sense of wonder, awe and delight; but rarely do we expect these feelings as part of our everyday experience as city-dwellers. Yet there are many “wild” things that we can include in our cities.

Here are three reasons why your commitment to re-wilding our city will ensure that you are remembered for the positive legacy you made in preparing our city for the future.

Adaptive capacity and resilience to future environments

We need wild places in our city to provide us with a barometer for environmental change and how we might respond most effectively. In the face of changing climate and increasing human populations, the most innovative cities are now looking to incorporate natural infrastructure such as plants, water and soils as part of the essential service delivery for their city. Their reasoning? The natural world has repeatedly proven its ability to deliver clean air, water and food; be incredibly difficult and expensive to replicate with technical solutions, and demonstrated enormous capacity to respond to, adapt and outlast every disturbance it has encountered. No other materials or systems can boast of such an impressive track record! Wild places are not only the canaries in our coal mines, they are also the emergency systems that can lead us back to safety.

Inspiration and prosperity

When you enter a wild space, the sound changes. You can see things that are not present in a more cultivated landscape. In Australia, we have wild things that are found no-where else in the world—spotting a platypus, koala, or echidna in the wild feels like you have been given a gift.

What new things would become possible if our cities residents and workers were able to encounter these experiences during their lunchtime walk?

Humility and leadership

In our fast-paced, highly connected world it can be easy to feel overwhelmed by the things we are trying to do. Wild places can help to remind us to remember the bigger picture. By visiting wild place we can recalibrate our understanding of where we fit in the world, and bring our problems back into the scale of the human world. They also provide our kids with spaces where they can exercise their imagination, creativity, problem solving, strength, balance, and extend their understanding concepts like risk, change, care, and responsibility.

Today represents a critical point in our city’s future, with a predicted doubling of the human population over the next twenty years. The decisions made today shape the fabric of our city in the future. Yes, wild spaces need to be well planned to protect both the environment and the people who spend time there. The process of re-wilding may even challenge us to rethink and reframe the things we thought we knew. But we have many tools and signposts that can help ensure we can identify and overcome these challenges.

We need wild spaces in our city for all sorts of reasons. For some people it will be the sounds, smells and immersive experience akin to the concept of forest bathing in Japan. For others it is a place for curiosity—where they can exercise their imagination, creativity, problem solving, strength, balance, and extend their understanding of concepts like risk, change, care, and responsibility. Or perhaps it is an opportunity to feel a sense of awe or beauty, or to seek inspiration from looking at life at its most complex, and also its most simple.

Wild places are the free radicals keeping the residents of our cities healthy and well, and businesses innovative and prosperous. Who wouldn’t want to be responsible for leaving a wonderful legacy like that!

about the writer

Keitaro Ito

Keitaro is a professor at Kyushu Institute of Technology and teaches landscape ecology and design. He has studied and worked in Japan, the U.K., Germany and Norway and has been designing urban parks, river banks, school gardens, and forest parks.

Keitaro Ito, Fukutsu City

The tidal flat in our town is very important wild habitat for species like the horseshoe crab (Tachypleus tridentatus), the black-faced spoonbill (Platalea minor, only 3,500 population on the world) and many kinds of fish and shellfish. It is called “Tsuyazaki tidal flat”, located in south part of Japan. This place has been nominated as one of the 500 most important wetlands in Japan. However, these days, the horseshoe crab population is decreasing, as are some shellfish and some seaweed species. I guess one reason for these declines is the lack of sand from around the area to resupply the coastal beaches.

In the 1970’s, there was no road around this tidal flat. Water and sand flowed freely into it from the surrounding hills. In the 1980’s the road around the tidal flat was constructed. I think this road stopped the flow of sands that supplied the tidal flat. These sands formed the sandbank that served as the habitat for the many living creatures. So I think we need to re-wild this area. My idea is to construct “small under paths in the road”. The costs associated with this re-wilding effort would be minimal, and we could use the road as usual. With the replenishment of the sand bank, the horseshoe crabs would be able to lay their eggs and the population would increase.

We have undertaken environmental planning in our town in 2017. https://www.thenatureofcities.com/2015/10/25/collaborative-project-in-city-planning-for-urban-biodiversity-in-japan/

Now we are moving to the practical studies in some sites in this city. Work on three important projects has begun: (1) preserving the sea coast pine forest; (2) restoration of the bamboo forest; and (3) nature restoration in the tidal flat.

The emphasis of the third project, nature restoration in the tidal flat, is my proposal to build a small under path for supplying small amounts of sand and water from the hill to replenish the tidal flat. This small under path proposal should be implemented to change not only the tidal area but also to improve the sea coast sand formation. Last year two sea turtles came back to this area to lay their eggs. These nests had to be relocated to incubation boxes for hatching because there is insufficient sand along the sea coast for successfully hatching sea turtles. This unnatural process is due to loss of habitat.

By creating the small paths for supplying the sands and water to the coast we are re-wilding the place and changing the future. The sands would be reconnecting the ecological network. We usually see and feel the environment around us is stable but I think we need some disturbance for habitat and our future. For example, the forest is regenerated by natural disturbance like strong wind, water and so on. When large trees fall a gap appears in the forest making way for a new generation of trees to grow.

In urban areas, the roads and city structure are sometimes too fixed by impervious concrete that tends to prevent small disturbances. Of course, disturbances that are too big are life-threatening. But I think small disturbances are needed for keeping a healthy environment even in urban areas.

about the writer

Mark Hostetler

Dr. Mark Hostetler conducts research and outreach on how urban landscapes could be designed and managed to conserve biodiversity. He conducts a national continuing education course on conserving biodiversity in subdivision development, and published a book, The Green Leap: A Primer for Conserving Biodiversity in Subdivision Development.

Mark Hostetler, Gainesville

Elevator moments with a mayor

1. Economic: One of the first things I would mention to the mayor is that targeted areas could be re-wild without any cost to the city. These areas in particular, would represent a cost savings over the long term. How? Maintained parks are an annual cost to a city. Re-wilding portions of these parks would eliminate some maintenance costs. One would simply calculate how much money is being used to mow turfgrass and maintain structures to make the area accessible to humans, such as park benches, lights and light poles, etc. Once maintenance costs for proposed re-wild areas are calculated, the savings could be used to restore these designated wild areas. In fact, the costs to start the restoration process would decrease over time, resulting in a savings to the city. For example, if planned re-wilding areas costs $50,000 a year to maintain, then this money could be used to initially create these wild areas. Over time, these costs would decrease as mother nature takes over and only minimal maintenance is needed. There is a working example of this in Pinellas County, Florida. The county has created an initiative to have a portion of county parks to return to nature. Called “no mow” zones, the essential idea of this effort is to restore low traffic areas in county parks to native fauna and flora (see http://www.pinellascounty.org/park/no_mow.htm). The public is still invited to explore these wild areas, signage informs residents about the project and explains the transitional period and that going back to nature takes time. Money saved from not mowing these areas goes towards the signage and restoration activities (e.g., removing invasive exotics).

2. Selection, Restoration, and Maintenance: Once the go ahead is given to re-wild areas, the next step is to determine low traffic park areas that have some vegetative structure that would readily revert to nature if given a chance. For example, marked re-wild areas can be near natural areas where seeds would be dispersed by wind or by wildlife. I envision a dynamic marketing campaign to engage the local community in this selection process, creating excitement about the natural area to come. Other particularly attractive areas for re-wilding include manicured parks that border semi-natural areas. Park areas near these semi-natural parks would be given priority to go wild as the nearby natural areas serve as a seed source for the restoration process. Think of the seed rain coming from the nearby natural areas, helping to establish native plants. Eventually, restored areas next to existing natural areas would make a bigger, natural patch and thus more habitat for wildlife.

Most likely, some built structures (e.g., paved areas) would be removed and perhaps some native plants would be planted to jumpstart the restoration process. Funds for these activities would come from the money saved from not mowing/maintaining an area. Residents in the area could come to “plant a tree day” becoming actively involved in the restoration process. Some areas may need invasive species removal; another opportunity to include the local community. Educational signs placed around then re-wilded areas explain the process of restoration (as it could take many years and may go through several scraggly stages). Construction of a walking trail around portions of the perimeter with one or two access points would lead people into the interior of these areas to experience the sights and sounds of nature. However, education near these access points should indicate how visitors are stewards and the importance of limiting human impacts (e.g., staying on trails, not dumping yard trash into the interior, and no pets).

These wild areas should not be thought of as pristine, no exotics at all types of areas. Although management would be needed to control some particularly nasty invasive plants (not to mention exotic animals such as feral cats/dogs), we should think about restoring urban habitats in terms of “reconciliation ecology.” Here the goal is not to return to pristine, indigenous habitats but to implement strategies that simply increase the diversity of native species in cities. Conserving species diversity where people live, work, and play means providing areas where nature takes over a bit. We can have parks that are geared more towards humans—think mowed areas with some large trees, playgrounds, etc. But for city inhabitants to understand and experience their true natural heritage, we do need more wild areas where the primary landscaper is mother nature. Many iconic species, such as migrating birds, require these wild areas as habitat, and would not occur in cities without them. Overall, there is an understanding that wild areas are still influenced by and are accessible to humans that live nearby. The trick is to minimize the negative impacts and to maximize positive impact to native species and humans alike.

To the mayor, I would describe these wild areas as controlled chaos. Here, the wild areas are bordered with maintained features such as trimmed vegetation, perimeter trails, and even sculpture. It would not cost the city any additional money. The mixture of manicured parks and re-wild areas is critical to house a variety of species in cities where people can enjoy and become aware of their natural heritage.

about the writer

Jala Makhzoumi

Dr Jala Makhzoumi is an Iraqi architect and academic who specializes in landscape design, with expertise in postwar recovery, energy efficient site planning, and sustainable urban greening.

Jala Makhzoumi, Beiruit

Rivers and streams are the surest way to re-wild Mediterranean cities in the twenty first century. Regardless as to how big or small, people and nature have for millennia competed to benefit from the climatic sheltering and rich environmental resources of riverine landscapes. Rivers swell up with the melting of snow and during the rainy season but many remain dry for the rest of the year. With the exception of large rivers, however, streams and dry watercourses are undervalued, slowly vanishing in coastal cities, swallowed by building encroachment. Many are used to dump solid waste and sewage. As a result, they are channelized and diverted into culverts, their memories erased from the collective memory of the urban inhabitants.

Abuse and misuse has come to undermine the potential of rivers and dry watercourses to enhance the quality of living for the urban inhabitants if restored to their natural state as healthy ecosystems and living landscapes. Re-wilding urban streams is undeniably visionary and a huge challenge. The benefits however are equally immense. Healthy watercourses, no matter how small, have the potential to form green corridors that punctuate the urban fabric and provide distinctiveness and a sense of place. Similarly, seasonal fluctuations, rather than being a problem, remind urban inhabitants of the cycles of nature in an otherwise timeless existence. A restored, healthy ecosystem will demonstrate nature’s regenerative power, its ability to restore and sustain. The river landscape becomes once more a wildlife habitat and a place where people experience nature. Just as significant is the revival of the river memory, often inseparable from that of the city and its inhabitants. The river becomes an amenity landscape, a place to promenade and cycle, to rest and reflect away from the stressful environment of the city. Above all, rivers are ecological corridors that ensure landscape connectivity. As such, they re-anchor the city in the larger landscape and link terrestrial ecosystems with coastal ones.

The opportunity to put my words into action presented itself to me in a project in the city of Saida, Lebanon[1]. Like all coastal cities in the country, Saida streams and two small rivers punctuate the landscape, many covered and forgotten. Speaking to older residents I was amazed and inspired to learn that rivers were still alive in the collective memory even though they had long disappeared from sight. Restoring Saida’s rivers, promoting their use as green corridors and amenity landscapes became integral to the future vision and strategic development framework proposed by the project team.

At first, my proposal for reviving the streams was ridiculed and opposed by the municipality, the client. Their argument was that there were no rivers, only sewers. I persevered arguing that the process was long but doable. The first step is to embrace the concept of re-wilding[2] and convince municipal authorities that rivers are not a “problem” that requires a solution but a potential that should be seized and capitalized. Once convinced, restoring the riverine ecosystem begins with redirecting sewage discharge away from the river channel and separating stormwater from sewage discharge. Demolishing the concrete encasement and restoring the soft river verges can follow. The choice of planting is also critical. Here, the vegetation of healthy rivers will provide inspiration and guidance.

The vision proposed by the project became the inspiration for local activist groups[3] that continue to fight to realize the project vision, working on the ground, to secure funding to clean the river, hold community meetings to raise awareness.

In choosing to talk about rivers, my aim is to demonstrate that re-wilding can and should be a place and culture-specific approach. Re-wilding Mediterranean coastal cities would differ fundamentally from bringing nature into cities in temperate climates or those in arid regions. Can we use the discussion platform provided by TNOC to explore different ways of re-wilding? Another facet of re-wilding worth exploring is the role of the various stakeholders, local NGOs, municipal authorities, and the public at large, in the long-term process of inviting nature back into our cities.

Notes:

[1] For details of the project, Saida Urban Sustainable Development Strategy, see http://www.medcities.org/web/saida and http://www.medcities.org/documents/22116/0/USUDS+Brochure_eng.pdf/1b0711ef-4e2f-4a1e-9bee-5858de9b22f0 accessed 04/11/2017.

[2] The term I used was ‘greening’, which implies cleaning the riverine environment and rehabilitating the watercourse as amenity landscape.

[3] https://lilmadinainitiative.wordpress.com/ accessed 06/11/2017

about the writer

Juliana Montoya

Juliana Montoya is a researcher at the Humboldt Institute, Colombia, where she works with biodiversity in urban-regional environments. She is an architect with a Master of Science degree in Conservation and Use of Biodiversity. Her main interest is to promote urban biodiversity as a crucial element of city planning, with a special emphasis on the role of citizens in territorial management.

Juliana Montoya and Juan Azcárate, Bogotá

(To read this post in English, see here.)

Asilvestrando ciudades: Una perspectiva desde la biodiversidad latinoamericana

Analizando la idea de asilvestramiento de las ciudades (re-wilding cities) como espacios que permiten la vida de especies de forma natural y espontánea en lugares diferentes a su área original, nos lleva a pensar en la ficción de cómo sería el mundo sin nosotros. Alan Weisman en su libro The World Without Us, nos muestra el impacto de la desaparición de los seres humanos y la forma en que las ciudades se habrían de deteriorar dando paso a la naturaleza. Esto nos lleva a imaginarnos un paisaje de ruinas asilvestradas y preguntarnos si esta conformación de lo silvestre y la infraestructura humana, ¿nos ofrece un escenario de mejores ciudades?.

En la planeación tradicional de las ciudades, ya existía una concepción higienista y aséptica de la naturaleza. Una idea del orden impuesto y el control sobre lo que no conocemos o sobre las otras formas de vida y con una postura estética de lo bello de la naturaleza bajo el hacha del orden del color y las alturas como mecanismo paisajístico. Esta domesticación de la naturaleza en las ciudades lo leemos incluso en cartas de Francisco José de Caldas (científico, ingeniero militar, geógrafo, botánico, astrónomo, naturalista y periodista de la antigua Colombia) que a inicios del siglo XIX percibía lo salvaje y desconocido como caótico y sinónimo de peste y enfermedad. A esto, Caldas dice que “…al encontrarse impresionado por la exuberancia de la vegetación andina (…) las plantas se han esparcido sobre la superficie de los Andes sin designio, y que la confusión y el desorden reinan por todas partes” por lo que entonces determina que “la única forma de controlar la selva es haciendo con ella precisamente lo contrario a domesticarla: exterminarla” (Pinzón, 2011).

Sin embargo, hoy en día podemos entender la interdependencia que tenemos con la biodiversidad de la cual hacemos parte y cómo en la medida en la que reconozcamos los procesos ecológicos en la planeación de las ciudades es que esto podría desafiar el modelo urbanístico tradicional (Montoya y Garay, 2017) en busca del bienestar para todos los seres vivos.

Pensando ahora en cómo evolucionar en la construcción colectiva de mejores ciudades a través del asilvestramiento urbano donde la naturaleza puede ser natural y beneficien la salud y el bienestar humano, es cuando se nos ocurren ideas para convencer a un alcalde a desafiar el modelo urbanístico tradicional:

En las áreas urbanas, los espacios públicos resultan ser un espacio nostálgico en nuestras ciudades ya que nos ofrecen recreación, esparcimiento, deporte, identidad, ocio y demás, relevantes para la dinámica de los habitantes urbanos. Normalmente las ciudades colombianas poseen bajos índices de m2 de espacio público accesible por habitante. Es por esto que dentro de los elementos que componen lo verde de las ciudades, podrían existir una nueva categoría de infraestructura verde como espacios de asilvestramiento urbano espontáneo, que pueda albergar más equitativamente la multifuncionalidad de un área verde (más allá de la típica oferta de espacios para perros y para juegos infantiles) con altos niveles de biodiversidad y una oportunidad para una apropiación social del lugar.

Esto le aportaría también a aumentar los espacio público de la ciudad por habitante, por lo que mejoraría sus indicadores y se podrían generar proyectos de acciones locales para la biodiversidad (Montoya, 2016). Por ejemplo, sería interesante medir y comparar los costos-beneficios de los desiertos verdes (gramas, césped) con lotes baldíos o residuos viales que favorezcan el desarrollo espontaneo de lo silvestre y que esté sujeto a la construcción colectiva. Esto también podría resultar en proyectos educativos ambientales que nos orienten a cómo percibir la belleza que hay en la maleza por su función ecológica, por la sucesión hacia el asilvestramiento de las ciudades y por la convivencia con la fauna “temida” como chuchas, abejas, murciélagos (Mejía, 2016) que cumplen papeles determinantes en los ecosistemas de la ciudad.

Es interesante ver la propuesta de la Nueva Agenda Urbana de ONU-Hábitat bajo la insignia de “ciudad para todos” incluyendo la idea del asilvestramiento urbano en donde se puede permitir que lo silvestre encuentre un equilibrio en la ciudad y que busque la real accesibilidad para todos, incluso de lo silvestre.

References

- Weisman, A. (2008). The world without us. Macmillan.

- Pinzón, F. M. (2011). Una geografía para la guerra: Narrativas del cerco en francisco José de caldas. (spanish). Revista De Estudios Sociales, (38), 108-119.

- Montoya, J., y Garay, H. (2017). Desafiando el modelo urbanístico. Naturaleza urbana: Plataforma de experiencias. En Moreno, L. A., Andrade, G. I., y Ruiz-Contreras, L. F. (Eds.). 2016. Biodiversidad 2016. Estado y tendencias de la biodiversidad continental de Colombia. Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt. Bogotá, D. C., Colombia.

- Montoya, J. (2016). Reconocimiento de la biodiversidad urbana para la planeación en contextos de crecimiento informal. Cuadernos de Vivienda y Urbanismo, 9(18), 232-275.

- Mejía, M. A. (ed.). Naturaleza Urbana: Plataforma de Experiencias. Bog

otá. Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt. 2016. 208 págs.

Re-wilding cities: A perspective from the biodiverse south

Analyzing the idea of re-wilding cities as spaces that allow nature to develop naturally and spontaneously, despite being introduced to a place outside of its original area, leads us to consider the idea of a world without humans. In his book The World Without Us, Alan Weisman illustrates the impact the disappearance of human beings would have on the Earth, and the way cities would give way to nature, eventually deteriorating. Such an image begs the question: Does combining the wild and the human offers opportunities for better cities?

However, today we understand to a larger extent our interdependence with nature and its value for cities. This understanding can challenge the traditional urban model that controls and treats nature aseptically (Montoya and Garay, 2017) and can contribute to the well-being for all living beings.

It is when thinking on how to evolve in the collective construction of better cities through urban re-wilding (the creation of urban spaces where nature can be natural, spontaneous and benefit human health and welfare) that one can come up with ideas to convince a mayor to challenge traditional urban models:

In urban areas, where most of us now live, public space offers recreation, sports, identity, and leisure opportunities of significant relevance to our wellbeing. However, most cities, in particular Colombian cities, normally have low levels of accessible public space for its inhabitants. This relative lack of public space in Colombian cities can improve if, within the elements that make up the green of the cities, we also consider the need for green spaces that support a more spontaneous re-wilding of urban nature. Such spaces could contain high levels of biodiversity as well as social components, providing for more real multifunctionality (going beyond the typical space for walking dogs and children´s recreation) and becoming economically and sociably feasible.

These spaces can contribute toward increasing the availability of public space per inhabitant, improving city indicators and generating local action projects for biodiversity (Montoya, 2016). For instance, it would be interesting to measure and compare costs and benefits between green deserts (lawns) and vacant lots or abandoned roads that favor the spontaneous development of wild nature and that are subject to collective construction. Moreover, wild urban spaces could provide educational possibilities to create an understanding of the beauty and value of nature not purely based on aesthetic reasons but also on functional traits. This could lead to an appreciation of weeds, for instance, and to understand the importance of learning how to coexist with “feared” fauna such as bees and bats (Mejía, 2016), which play determining roles in city development and human well-being.

An interesting idea is to consider the proposal of the New Urban Agenda of UN-Habitat “the city for all”, where we would love to see it allow the wild to find a balance in the city, and to seek real accessibility for all to the city, including that of the wild.

about the writer

Juan Azcarate

Juan Azcárate is a research at the Humboldt Institute, Colombia, where he works with biodiversity in urban-regional environments. He is an environmental planner with a PhD degree in Land and Water Resources Engineering, and his main interest is to use strategic approaches to enhance decision making and promote pathways towards sustainability.

about the writer

Daniel Phillips

Daniel Phillips is an urban ecologist and landscape architect. He is the co-founder of COMMONStudio, a collaborative creative practice with independent projects and research spanning many countries.

Daniel Phillips, Bangalore

The positive correlations between public health and urban greenspace are clear. Yet building the political will, public engagement and financial capital for the establishment and maintenance of new greenspaces in cities is a much more murky prospect—one that often far exceeds the capacity and duration of a mayor’s average term of office.

It’s here that the notion of re-wilding can be employed as a viable—even visionary—strategy for contending with the many parcels of underutilized (or overly maintained) land already held on city balance sheets. Recent research shows that up to 20 percent of urban land in even the densest of American cities like New York is now lying “vacant”.

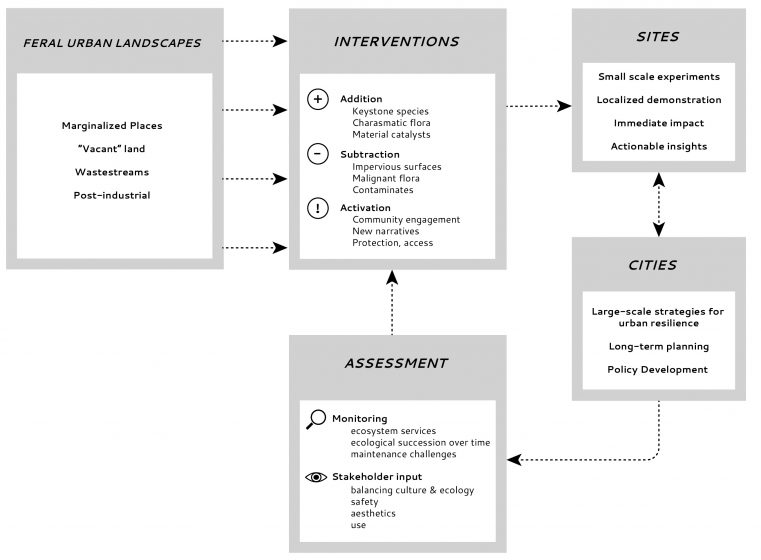

There is no such thing as a “vacant lot”

First, it’s important to think beyond the notion of a “vacant lot”, because “vacancy” implies a condition of emptiness, and thus a state of devaluation. If we look closely at such places, we find in fact that they are already teeming with rich networks of biotic life, history, and culture of all kinds. Whether a dandelion emerging from a crack on the sidewalk, or a healthy meadow thriving in a former parking lot, these are moments self-willed ecological poetry right under our noses in the margins of the city. They invite us to realize that “wild” is not a condition of the past, but an active and unfolding part of the present. Rather than referring to such places as “vacant”, we might instead employ the term “feral” to reflect their state of being untamed by the conventions of domestic urban life, and their knack for escaping the obsessive regimes of control often imposed by city maintenance crews.

Re-wilding is sound urban policy

If this isn’t enough to convince you of their inherent virtues, there’s also the notion of ecosystem services, what some refer to as the “what have you done for me lately” school of ecological thought. In an urban world marked by the inevitability of urban megastorms, extreme heatwaves and droughts, the provision of pervious and densely vegetated surface conditions can be a matter of life or death. They act like urban sponges and parasols to reduce the risk of floods, maintain safer temperatures during heatwaves, and provide habitat to charismatic urban wildlife that keep insects and mice in check. Perhaps best of all, feral urban landscapes already provide these services virtually free of cost to local taxpayers and municipal governments.

But the question remains: How might we further activate these places with intention without negating their essential quality of wildness? Formalizing them into public parks in any traditional sense would prove too costly and contradict the spirit of re-wilding altogether. Yet just rebranding them as “urban wilderness” and walking away would also miss a vital opportunity to understand their complexity, and direct their development in ways that could further bolster the vibrancy and resilience of the city.

It’s time to integrate tactics and strategies

For the past decade at COMMONSTUDIO, we have been approaching this challenge at many scales. We work with and within feral urban ecosystems, attempting to collaborate with them from the bottom up. Experiments such as the Greenaid Seedbomb Vending Machine and our “Pile Studies” propose the addition of charismatic species (such as wildflowers) into marginalized landscapes to increase their cultural and ecological resonance. The Metropoliz Future Forest proposes the careful subtraction of pervious surfaces (what we refer to as “designed disturbance”) in the context of post-industrial sites to accelerate existing processes of ecological succession.

Rather than attempt to assert total control, or design sites toward conditions of stability and stasis, these tactics are conceived as an ever-growing toolkit of actions that incorporate the condition of wildness as an active and unfolding process within the city. In this way, they are simultaneously intentional and unpredictable. They require a minimum of equipment, infrastructure, investment and maintenance, often deployed in direct engagement with local communities and stakeholders. To date, we’ve tested these tactics at small scales in the context of individual sites in cities such as Los Angeles, Rome, and Bangalore, monitoring their impact and development over time. Yet we know the power of these approaches are only as good as their ability to scale. Integrating tactics with strategies means creating a critical feedback loop between bottom-up and the top-down in which broader ecological goals (such as the creation of urban habitat corridors, integrated stormwater management, etc.) are actively informed by hard-won insights on the ground.

In short, mayors have access to lots of land and few ideas, urban practitioners have lots of ideas and too little agency. So it’s a perfect match. Let’s take a portion of the existing parks maintenance budget and reallocate it toward the establishment of a semi-autonomous “Bureau of Urban Rewilding”. This could provide a vibrant locus for urban ecological experimentation on larger scales. Interdisciplinary teams could come together, conduct research, engage in monitoring, and develop broader urban and regional strategies based on their findings.

Similar models have already proven successful in forward-thinking cities such as Singapore. This autonomous bureau would likely pay for itself over time through deferred maintenance costs of public land.

In the meantime, just imagine the headline potential: “With the single stroke of a pen, intrepid mayor saves taxpayers millions, consecrates acres of new green space to make the city safer.”

about the writer

Mohan Rao

Mohan S Rao, an Environmental Design & Landscape Architecture professional, is the principal designer of the leading multi-disciplinary consultancy practice, Integrated Design (INDÉ), based in Bangalore, India

Mohan Rao, Bangalore

Madam Mayor: The value of “nature” in the urban context is proven beyond doubt. Starting from the pressing need for recreational spaces at the height of industrialisation, the value of open spaces for the city has been further reinforced in recent times from the ecosystem services perspective too. However, our historical obsession with design and control of every aspect of the city has meant that there is very little of the natural in open spaces. Parks and woodlands continue to be designed to the last inch; rivers and stream corridors are directed and shaped to satisfy our visual aesthetic.

So why is it important to bring back the wild? Because the benefits of doing so are not just limited to the psychological well being of people or the carbon sinks they provide, substantial as they are. The immense range of benefits—both tangible and intangible—are actually critical if cities are to continue to provide a decent quality of life to its citizens. Specifically, with the looming disaster of climate change facing humanity, it is imperative that we re-wild our urban landscape.

The real challenge is not merely in re-wilding parks and open spaces but in de-engineering our cities. For a couple of centuries now, growth and development have been pegged as corollaries to built infrastructure and engineered systems.

So, why should this be de-coupled now? My own city, Bangalore, with an urban history of over five centuries, was traditionally developed around a well-integrated network of lakes, stream corridors and wetlands. Of the recorded 260-odd lakes 100 years ago, less than 30 survive today and of these only a handful are deemed healthy. For the city, this has meant increased instances of flooding, disappearance of several species of birds, increase in pollen allergies, increased heat waves—the list is long. I can prove to you, madam Mayor, that the rate of death of these lakes is directly proportional to the increasing “engineering” of urban spaces and services: stormwater networks, waste water treatment, etc. In fact, this can be proved in almost every city imaginable! This is a direct outcome of over reliance on engineered systems, seen as infallible and more reliable compared to natural ones. The more we rely on engineered systems, the less we value the presence or need for natural ones. And the lesser we value anything, the greater the likelihood of losing them.

This may seem a Luddite attitude, but allow me an analogy of the human body. Medical science and technology has advanced enough that we are able to replicate specific functions of human organs. So, in cases of extreme medical distress or threat to life, artificial organs are implanted to compensate for a failed organ; artificial knee joints, dialysis for kidneys and so on. But no rational person would replace a healthy organ with an artificial one simply because one wants to live longer! The reason I give the example of this extreme situation is because this is exactly what we have done in our cities! We convert natural streams into storm water carrying channels, reorder their natural edges with built embankments, reroute their natural paths, replace natural grasses with lawns, and so on. We continue to do so in our secure knowledge that we have the means and the capability to improve upon nature. After several decades of these surgeries to nature, the results are increasingly obvious: reduced biotic life due to loss of spawning edges, increased flooding in even non-extreme weather, increased cost of maintenance, to name only a few.

Would the alternative mean having unmanageable and grungy parks in our cities? On the contrary, it means having more natural refuges that offer a range of ecosystem services but costs the city a fraction of the current municipal spending. The way to go about re-wilding our city is not merely by withdrawing all maintenance services but through a careful process of strategic de-engineering. This will entail identifying open spaces with excessive built interventions and replacing them with natural solutions; undoing the errors of the past through current wisdom. This will also mean re-educating our city managers, planners, architects and most importantly the citizens. It is important to communicate with all stakeholders in understanding not only reduced costs (and hence taxes!), but also make them aware of benefits to expect in the short and long term; benefits that can be benchmarked and measured. Depending on the scope and scale of interventions, these would include increased biodiversity, reductions in pollen allergies, reduced flooding incidence, decreased urban heat islands, healthier water bodies, increased aquatic life, and so on. The reduction in public health costs alone would more than justify any small increase in project design and intervention costs in the initial years.

If we were to agree, we could identify strategic areas of intervention as pilots; where the disruption to existing services would be minimal with measurable benefits. The ideal way to do this would be to identify short-term interventions where the benefits can be seen well within your term in office! Of course, a more carefully drawn out plan for the larger city region will strategise the gradual re-wilding over a period of several years and I can assure you that all other things being equal, you will remain in office for an extended period of time!

about the writer

Kevin Sloan

Kevin Sloan, ASLA, RLA is a landscape architect, writer and professor. The work of his professional practice, Kevin Sloan Studio in Dallas, Texas, has been nationally and internationally recognized.

Kevin Sloan, Dallas

Wild Dallas

This offering to the TNOC Roundtable on re-wilding is written in the manner of a “Horizon” Magazine memo, from myself to the current Mayor of Dallas, Michael Rawlings.

NOTE: “Horizon” was a magazine published in the US from 1958 to 1989 known for bringing culturally sophisticated articles on various topics to an educated public. A regular feature of each issue was a fictional letter or memorandum written by a great leader / artist to of one era, to another of a different time; such as from Julius Caesar to Robert Moses on the problem of urban traffic.

To the Honorable Michael Rawlings, Mayor of Dallas, Texas

As a fellow citizen of Dallas, Texas and a practicing landscape architect and city planner, I am writing to shed light on several environmental issues that could embolden the future of Dallas. Moreover, the recent destruction of Buffalo Bayou Park in Houston by Hurricane Harvey, shines an even brighter light on how our city might avoid similar mistakes, especially with regards to our approach for the colossal, 10,000 acre Trinity River Park. Key to both are new policies and landscape strategies that affect our resource consumption and water use.

Dallas is on the same latitude as Baghdad and North Africa. As just one part of a seven million acre urban agglomeration that grew to envelope twelve other county seats and numerous small towns, Dallas’ current cultural preference for using the drinking water supply to transform the original Blackland Prairie ecology into fine lawns that simulate an English landscape needs serious reconsideration.

While the similarly vast geography of Houston and its impervious infrastructure has drawn a lot of criticism in the wake of the flooding by Hurricane Harvey, what is being overlooked is their similar preference for highly watered lawns and landscapes. Landscapes that are saturated with irrigation waters are like a sponge that’s already satiated. Stormwater rapidly runs off with nearly equal acceleration from the paving as it does the lawns. What is needed are policies to evolve a new cultural preference—a new aesthetic—that is also beautiful and indestructible to the unpredictable forces of climate change.

A new development in environmental design and landscape architecture known as “Re-wilding” may offer a more cost effective and resilient future.

Re-wilding re-establishes the original nature and ecology of an area, as closely as reasonably possible, given that some alterations to a native mix of plants will to armor the installations against invasive species that are certain to attack it.

Why spend millions of taxpayer dollars, mowing the vast landscape fragments that surround a boulevard or park to look like an English estate, when these areas could be re-committed to a landscape that, once established, will largely tend and protect itself?

Blackland Prairie grasses evolved in our inefficient ecology by developing root systems that extend ten to sixteen feet into the ground. These robust root systems not only enable the grasses to survive the demands of our drought and deluge cycle, they also serve to wick stormwater into the ground. While Dallas may not have the same vulnerability to hurricanes as Houston, we are susceptible to flash floods, which have claimed several lives. Although it might seem improbable that re-wilding can save lives and preserve the majority of our drinking water supply to survive a mega drought, perhaps these points demonstrate the potential cost effectiveness of the idea.

But there are other reasons that might also interest you and your interest in business development and local economics.