Across the street are rows of luxury, high-rise condos and villas of the elite, gated community known as Bosphorus City. A couple of decades ago, this was the site of one of Istanbul’s largest trash dumps, a factoid I read on the trail map I’m following. Like many parts of the city, and Turkey, in general, the land was reclaimed and sold for housing development initiatives most ordinary people can’t afford.

Behind me is a working-class neighborhood with modest single-family homes and squat, square two and three-story apartment buildings. A textile factory has a ground-level shop selling samples of shirts and pants made on the upper floors. Kids, sporting jerseys of their favorite local football clubs, kick a ball around in the street. An old man with a cane makes his way uphill carrying a bag of tomatoes. A cat curls up on the corner, in no rush to be anywhere.

Suddenly, a rooster and a few hens jump through a hole in the park fence. One of the neighbors behind the park cut the metal spokes so his chickens can peck and find crumbs of left-behind picnic fare. This public space is their private farm.

In many ways, this scene, and others I have seen while walking parts of the Between Two Seas and Hiking Istanbul trails, sum up the push and pull Istanbul faces.

On one side, government officials search for ways to modernize infrastructure, stimulate economic growth through widespread construction projects and accommodate the estimated 15 million people that live in Istanbul. On the other side, beyond the day-to-day routine of getting by, there is an undercurrent of growing concern around the issues of preserving natural green spaces, providing just and equal access to social and economic opportunities, and controlling overdevelopment.

Footsteps through time and development

I’m back in Istanbul, a complete diversion from our Bangkok-to-Barcelona foot journey, because I want to see what soon may be lost.

In autumn of 2017, while walking along the Black Sea, I had heard tidbits about the proposed shipping canal project that would create a massive, parallel, alternative route to the heavily-trafficked Bosphorus Canal. This spring, news of the construction of a third Istanbul airport reached my ears. Then, Instagram posts from the Culture Routes Society’s Between Two Seas hiking trail further piqued my curiosity about what is happening on the fringe of Istanbul.

From everything I could gather, Istanbul’s urban sprawl and the government’s plans to hit lofty economic targets before 2023’s 100th anniversary of the founding of the modern Turkish republic was on a crash course to swallow up the last of city’s natural green spaces. As a person walking parts of the planet, I felt an urgency to walk through these precious and endangered spaces.

The Between Two Seas route offers an invitation to do that.

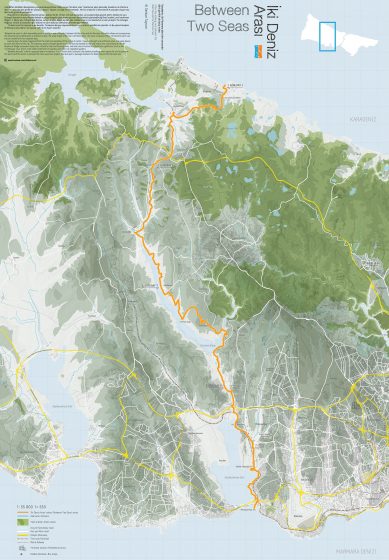

It was set up as a four-day, 60-kilometer hike starting at the Black Sea in the north and ending in the Marmara Sea in the south. It unpeels layers of development, leading walkers from the outermost periphery of the city through rural areas, forests, water basins, vegetable farms, a Neolithic-era cave that marks the city’s oldest settlement, housing complexes, new construction sites, parks, marginalized neighborhoods, historical ruins and other places of cultural importance that define Istanbul’s past, present, and possible future.

“What can you do between two seas? This was the question. In post-modern life, people don’t walk from one sea to the other,” says Serkan Taycan, founder of the Between Two Seas trail who blends his background in civil engineering, urban planning, and photography to focus on urban and rural transformation. “There is a narrative behind the trail. The Between Two Seas trail goes from the rural villages to the water basins to the urban fringe to the gated communities to the new apartment blocks to the lagoon to sub-city centers. Layer by layer, step by step, you can observe the chronology of urbanization in Istanbul.”

Some of the four-day route—originally opened in 2013 before it was clear where the proposed canal could be located—has already been impacted. The northern-most section, once home to forests and fresh-water lakes used by hundreds of migratory birds, is mostly under the concrete of Istanbul’s third airport; the new airport is scheduled to open in late 2018 and will eventually replace Ataturk Airport about 50 kilometers south.

A new road leading to the third Bosphorus bridge, which will help Turkey establish another way to move goods east and west between continents, has also cut away at the city’s natural environment. If that wasn’t enough, there is an ever-present threat that the once-protected lands in the northern part of Istanbul will continue to disappear as recent legislative changes expand the possibility for further development, as reported by National Geographic in March 2018.

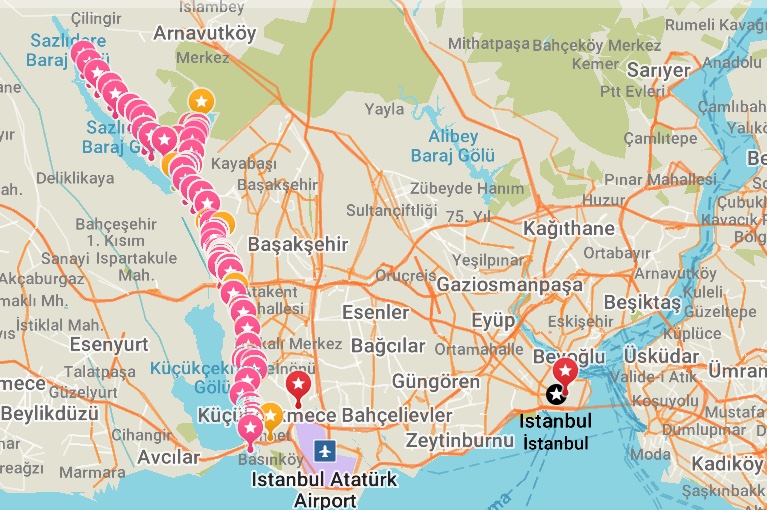

I take the advice of Taycan and Nick Hobbs, one of the founding members of Hiking Istanbul, which has created a 700-kilometer network of trails around Istanbul that are accessible via public transportation. I head out to do a two-day walk on the Between Two Sea’s southern 30 kilometers from Sazlıbosna and the Sazlıdere Reservoir to Menekşe Beach. The open spaces and towns along these sections of the trail would be most affected by the proposed Canal Istanbul project, which seems to be inching closer to reality.

“The construction of the airport and motorway are done, and those green spaces are already lost. We hope the canal won’t be built. It will be a tragedy if it is built,” says Hobbs, who is also an artist, concert organizer, and climber. “It will destroy what is left of Istanbul’s north-to-south green corridor and quicken the destruction of the city’s east and west green spaces.”

I start out early from my hotel near Ataturk Airport, thinking I would reach Sazlıbosna about 9 a.m. But getting out of Istanbul’s daily chaos poses its challenges. A bus that was supposed to start near a central metro line never shows up, and after an hour of waiting and the help of a local who speaks some English, I find out that I have to take another tram to the end of the line and get the bus there. The delay means I won’t start walking until noon, but I’m eager to leave the city’s noise and crowds for the silence of rural spaces.

It’s hot and humid in mid-May, but the breeze coming off the reservoir makes the flat walk comfortable. I watch storks and gulls skim the water’s glassy surface and block out the sound of squawking crows fighting over remnants of food. Green farmland and high-voltage towers string remote towns together with the necessities of food and electricity.

I walk the waterfront’s edge, disheartened to see trash piled up under almost every tree offering a shady spot for picnickers. In Turkey, like many other countries I have walked, I have seen the locals’ affinity to eat and relax in nature, but have made myself crazy trying to understand how they can spoil these beautiful places with plastic bags and bottles, styrofoam trays and soda cans. A herd of grazing cows restores my faith in nature’s survival, and I wave to the cow that has waded into the water to cool off.

There are some red and white and blue and orange trail markings pointing the direction southward, but I end up losing the path or reinventing one so I can I have a better vantage point. I climb a small hill and walk a dirt trail pounded down by a tractor. A local warns me to be careful of snakes sunning themselves.

I come to an old quarry, and the image of big white blocks submerged under floating algae conjures up an eerie, mystical stillness of time forgotten. A few curves later, a shepherd leads his sheep through scrub and the hazy views of big apartment buildings rise up on the horizon. The sweet scent of yellow flowers, which I recognize as ginesta from back home in Catalonia, reaches me. I close my eyes remembering this smell.

I cross into the small village of Şamlar. I see four things as I enter the town: the mosque’s minaret, a sign advertising Canal Istanbul land sales, a tea house, and a restaurant. It’s the sign I get stuck on. I wonder how many people are selling land that may have been in their families for generations, and I wonder who’s buying the land and at what price. I have seen plenty of real estate signs and development projects along the Black and Mediterranean seas, and it appears that the Canal Istanbul project is now ushering in speculative land buying and selling, something that certainly will give a short-term boost to Turkey’s real estate and construction industries, important GDP sectors.

I make a mental note to backtrack to see the old Ottoman dam just outside of town and make a beeline to the restaurant for a late lunch and a few minutes of reprieve from the heat.

A young man approaches me. He is eager to speak English. He insists on walking with me after lunch. “There are dogs. Maybe there are not nice people ahead”, he tells me. I don’t know whether or not to believe him. Lluís and I have encountered dogs in many places, and yes, it’s possible to meet shady characters anywhere, but, I find people’s fears to be slightly exaggerated. I see kindness in his eyes, and I agree to the escort, slightly regretting my decision not to see the Ottoman dam before my rest break.

Although I know from the Hiking Istanbul’s field notes Hobbs emailed me that I am supposed to follow the waterfront towards the new dam at the end of the reservoir basin, my companion believes the path is closed. It is closed to vehicles, but neither of us is sure if it now also closed to pedestrians. Chatting about Turkey, Europe, and life’s troubles and wishes, we divert ourselves to a hilly path through a thigh-high grassy field and end up on a dirt road wide enough for cars. At the top of the hill, without any dogs or seedy characters showing up, my companion says he must return to work and waves goodbye. “I’ll friend you on Facebook”, he says.

I follow the road downhill and rejoin the waterside trail on the other side of the dam. Signs of urban life become more evident. Apartments, some old and some new, line both sides of the narrow, canalized river. Calls to prayer echo from different directions. It’s about an hour before sunset, so I take the fork in the road and climb up to the two-lane road where cars and trucks whiz by, a little too close to the non-existent shoulder I insist should be there. I’ll end the day here, waiting for a minibus with a woman and her son.

The next morning, I set out for my starting point, Yarımburgaz Cave, the site of one of Turkey’s oldest human settlements.

Finding the bus to the Güvercintepe neighborhood is easier than yesterday’s public transportation adventure, and locals tell me where to get off. Unfortunately, I end up about 75 meters higher than the cave, and the small streets that connect to the two-lane road that connects to the cave are about one kilometer away in either direction. I have to go one kilometer out, and one kilometer back to arrive at the point almost directly below me. I don’t see a clear way to the cave from where I’m standing without slip-sliding downhill, so I let go of the idea of visiting the cave. Still, from this high point, I can imagine how important this area must have been millennia ago with its access to water, fertile land, and hilly protective surroundings.

Walking through this neighborhood, I’m struck once again by the various states of construction happening on every block. Empty plots, half-built apartments, fenced-in areas with active construction underway are recurring images.

Further on, I see parked trucks on one side of the narrow, canalized river, and on the other side, I watch a shepherd move his sheep to a nearby pasture. I don’t know which one looks more out of place, but in today’s Turkey, they both seem to belong there.

I wind my way down to the main east-west motorway touching the north edge of Küçükçekmece Lake. From here, I can take Hiking Istanbul’s nature-centric route along the western waterfront and find Bathonea, a ruined Roman port probably used for lignite transportation. Or, I can follow the original Between Two Seas trail and enter denser urban areas. I want to see the urban sprawl, so I choose the eastern side.

I take an overpass over the well-used highway, and the sound of traffic haunts me. I have to avoid the rail lines, which are now in use. Looking at my digital map, I find my way to the park with the chickens.

With a few words of English, a few words of Turkish, my map zoomed into where I’m standing, and my Google translate app, I ask a man at a bus stop if he knows whether there are sidewalks ahead. I’m at a place where streets merge and become bigger streets. My walking experience tells me these intersections frequently lose their pedestrian passes.

He tells me there are sidewalks and asks me why I need them. “You can take a bus”, he says.

“No, thanks. I’m walking to the Marmara Sea”, I reply.

When he realizes that I am going to walk onwards, he invites himself along. I don’t want the company during this hot part of the day when I would rather not talk, but I do want to encourage people to walk their cities. I know he’s flirting with me, too, as silly as I look in my sun hat and walking outfit, but I know pretty soon his ambition will wane. I revert to a game I play when people say they want to walk with me, especially men who think they can outwalk me. I ask myself one question: How long will he last? Looking at his fresh-pressed shirt and pointy business shoes, I bet silently one kilometer. Certainly not the 10 kilometers I have left.

We chat a bit in the few common words of two languages we share and then fall into a silent rhythm drowned out by cars and buses. He asks me a couple more times if I want to take a bus, and I continue to say, “No. Really, I’m walking to the sea.”

Near the Halkali rail terminal, occupied with cranes and heavy equipment, I know the heat has gotten the best of my companion. He bows his head slightly and waves, saying he has to be somewhere soon and will take the bus. I’m surprised when I look later in the day at my map and calculate that he walked about 2.5 kilometers.

I get off the main road, follow the smaller road to the customs area and then route myself to Küçükçekmece Lake and its waterfront park.

The lake is immediately disappointing. It looks like sludge and smells worse than sludge. At least I have a well-manicured park and easy walking ahead.

It’s a proper city park with a nice walking path lined with trees and benches. There are blooming flowers, playgrounds, cozy gazebos, cafes, restaurants, and trash bins. People, young and old, sit on the grass or stroll in the shade.

Again, apartment buildings, in various states of construction serving various classes of the population, line the city-side border of the park. Construction sites are as common as pigeons.

I cross a stone bridge, walk under a highway and reach Menekşe Beach. I ignore the black shipping yard building that first comes into view. It’s an eyesore in all ways.

I stroll towards the twisted trees growing out of the sand and watch men and boys play in the surf. I had thought to put my feet in the Marmara Sea, but the cargo container ships in the distance and the slimy stuff floating on the surface, change my idea.

Instead, I lay across a tire swing in the empty playground. A seagull lands on a light pole. We stare at each other for a while. I can’t help thinking about what will happen to him and this place he considers his home. I can’t help think about what will happen to this place where millions and millions and millions call home.

Walking awareness

People ask Lluís and me all the time why we walk. One of our usual answers is “Walking is the most intimate way to see our planet.”

Walking brings with it a sense of awareness and connects us to the space we walk in.

This idea is embedded in the Between Two Seas and Hiking Istanbul trails. They are invitations to explore and discover what’s happening in Istanbul and to appreciate the rich flora, fauna, and green hinterland that still exists here.

“I have walked about 2,300 to 2,400 kilometers around Istanbul. I know the land around this city probably better than anyone”, said Hobbs. “People who are not in contact with nature, I think are missing something from their lives. There is a strong benefit for the soul of the city to have a good relationship with its hinterland. And, here it is at your doorstep. You can take a bus to it.”

Though the Between Two Seas trail was set up to be a tangible example of how places evolve during different phases of urban development, there is something to be said about how walking opens the door to social changes and broadens perspectives.

“Walking is the most pacifist way to resist something and walking together has been an important type of resistance throughout history”, said Taycan, pointing to the large-scale walks that helped people in many nations win more civil and women’s rights. “As an artist and citizen of Istanbul, this is what I can do. I can continue to invite people to walk. We have to remind people about the importance of walking. If these kinds of projects remind people of walking’s importance, that is an achievement in itself.”

Other photos

Jenn Baljko

Bangkok to Barcelona on Foot

Hiking Istanbul and Between Two Seas offer free group hikes around Istanbul. You can find out details on their Facebook pages:

http://www.facebook.com/hikingistanbul

http://www.facebook.com/ikidenizarasi

For latest information you have to pay a quick visit world-wide-web and on the web

I found this web site as a most excellent web page for latest

updates.