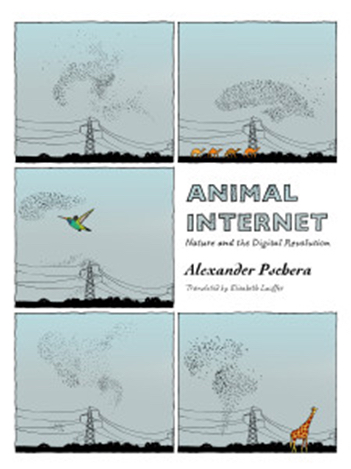

A review of the book Animal Internet: Nature and the Digital Revolution by Alexander Pschera (English translation from German by Elisabeth Lauffer). 2016. 209 pages.ISBN: 9781939931351. New Vessel Press. Buy the book.

Apply the sunscreen, fill the water bottle, and put the damn phone at the bottom of the pack. My (precious) time outside, in the woods or on the water, often starts with disconnecting from the internet. Losing that tether is for me a liberating experience that makes me present in my surroundings. Indeed, the internet and its distractions is usually considered an impediment towards bringing people closer to nature. Its offerings easily draw us (and especially our children) away from the complex beauty, the here-and-now wonder of the lives of plants and animals.

That is the prospect offered by Animal Internet by Alexander Pschera. Pschera draws on the example of Animal Tracker, an app developed by the Max Planck Institute that follows wild animals all over the world in near-real time, to offer valuable insights into the social, ethical, and a few of the management implications of an “internet of animals”. While light on technical details and some practical management considerations of remote sensing of wildlife, this smart book will trigger all kinds of interesting discussions about how tech can change our relationship with nature.

A bit of background: Animal Tracker draws its data from another free online infrastructure also housed at the Institute, Movebank, used by researchers to store and share data on daily and seasonal migrations. The aggregated information is used for research and management, and has that in common with apps with more targeted management objectives such as Whale Alert, which tracks individual whales and is used by agencies, NGOs, and shippers to reduce ship-strikes and other conflicts in Boston Harbor and other locations. But Animal Tracker also enables community sourcing of supporting information, including uploading individual observations and photos of tagged (and named) animals to Animal Tracker. It intentionally seeks to create an online community in support of public understanding, similar to those fostered by other apps such as iNaturalist and its Bioblitzs’ and City Nature challenges.

A bit of background: Animal Tracker draws its data from another free online infrastructure also housed at the Institute, Movebank, used by researchers to store and share data on daily and seasonal migrations. The aggregated information is used for research and management, and has that in common with apps with more targeted management objectives such as Whale Alert, which tracks individual whales and is used by agencies, NGOs, and shippers to reduce ship-strikes and other conflicts in Boston Harbor and other locations. But Animal Tracker also enables community sourcing of supporting information, including uploading individual observations and photos of tagged (and named) animals to Animal Tracker. It intentionally seeks to create an online community in support of public understanding, similar to those fostered by other apps such as iNaturalist and its Bioblitzs’ and City Nature challenges.

But the scientist behind Movebank and Animal Tracker, the ornithologist Martin Wikelski, sees a broader purpose. Tapping into the swarm intelligence of birds, turtles, fish, and insects by tracking their movements can be put to a broad array of purposes. Experiments are how underway to use migration patterns to predict and monitor earthquakes and floods, track vectors of disease and climate change, and monitor fisheries and agriculture. His ICARUS project, backed by the German and Russian space agencies, launched a satellite in February 2018 designed to facilitate the tracking of animals from space and lowering costs; a big step toward creating the animal internet that is the subject of the book.

It is the social and ethical dimensions of this change where Pschera, a student of philosophy and chronicler of the internet, makes his most astute observations. He posits that by tracking the movement of creatures in handheld apps and other digital tools can help increase the transparency of the natural world, and bring it closer to our lives and the life in our cities. The close observation of wild animals and any notion of developing a real relationship with them is difficult for most city residents. Naming animals, following their movement and perhaps feeding or reproductive success through webcams and posted photos, both illuminates their world and connects it with ours. It can help humanize apex predators like mountain lions or sharks or celebrate the arrival of migratory birds and fish.

Pschera does his best writing in describing how these interactions, and the power of social media and the internet generally in defining new social spaces and modes of being. He argues that our inherent need to relate to other living things can be well served by this digital world, in part by reducing the physical barriers and expertise once required to closely observe animals. This transparent nature is indeed critical to overcoming the traditional divisions of green and gray. By revealing life through the flexible mechanisms offered by technology around us we will bring animals back into our lives and reaffirm their utility to society. The animal Internet is “nature after nature”, a symptom of the Anthropocene era.

His discussion of the practical implications of the animal internet is not as well developed. The massive and practical challenges of storing and sharing data between scientists, agencies, and the public is not really acknowledged. I would have liked to have some more concrete examples and considerations for how the data could be displayed or shared, what has worked and what has not when it comes to using the internet to engage the public and drawing their interest into difficult policy and management questions.

Also relatively unexplored is some of the darker side of all this information gathering. Tracking animals is as valuable for poachers as it is for managers. Pschera argues that transparency will overcome these issues, and offers some good examples. But as with the internet of people, the harvesting of big data can be used for ill as easily as for good, and Pschera could have gone deeper into these questions.

But perhaps that is the point and the book’s real contribution. The internet of animals is surely coming here in one form or another, and with it “an ecology after ecology”. Coming to grips with what this means is more about ethics and understanding than quality assurance plans and user agreements. Pschera sees the animal internet as fundamental to revolutionizing human-animal interactions. It provides us with the basis for giving wild animals an individual identity that is critical to the protection of them and their habitat. The creation of stories about real animals will personalize them and make their lives real to people.

Can the data become as much of the management of cities as crowd-sourced traffic data and shopping patterns? That is left to others to determine.

Rob Pirani

New York

Click on the image below to buy the book. Some of the proceeds return to TNOC.

Add a Comment

Join our conversation