about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David’s dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to “fall back on”. So he bought a tuba.

Introduction

The word biodiversity is one of those words that lives happily in metaphor. But in detail, it is all over the map. Ask 10 people, you’ll get 13 definitions. Even ecologists use diverse definitions, that sometimes make distinctions between native and non-native species, but sometimes not; that alternate between indicating species or ecosystems and their services; and sometimes in the same conversation. And then there is the subtle and not so subtle distinctions between definition, meaning, and action.

There is important meaning and consequence inside the ideas of biodiversity, and ecology too. Indeed, there is a global wicked problem of biodiversity loss that finds expression at all scales. Biodiversity is a fundamental building block of ecosystems and their services. There’s definitely a pony in here. But what pony? And what pony do different people see?

Landscape architects are the practitioners of biodiversity’s meaning through their acts of shaping nature into “spaces”. They have their hands on definitions of biodiversity that they use in their work, and that we experience in the landscapes their create. But they aren’t necessarily the same definitions as a scientist’s. Or even a regular person’s. So, how do landscape architects view the word “biodiversity”? How does it find meaning in their work?

We asked twelve landscape architects this: As a designer—someone both supporting and manipulating the environment—what does the word biodiversity mean to you? Perhaps nothing? Perhaps something specific? Perhaps something metaphorical. What is it? And how does it find expression in your work, in your design?

about the writer

Gloria Aponte

Gloria Aponte is a Colombian landscape architect who has been practicing for more than 30 years in design, planning and teaching. She lead her own firm, Ecotono Ltda., in Bogotá for 20 years. She led the Masters program in Landscape Design at Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana, in Medellín. She is a consultant and belongs to “Rastro Urbano” research group at Universidad de Ibagué, and also the Education Clúster at LALI (Latinamerican Landscape Initiative).

Gloria Aponte

Biodiversity Design and Happiness

To select abundant species and biological associations is not enough to design with biodiversity and for people. We must satisfy human scale spaces and habitat.

A landscape design focus means the equilibrium between nature, built world, and human perception. To analyze the first, its composition functioning and ecosystemic services, the science realm would be enough, but the other two components let us have the complete spectrum; it is to say, the landscape.

Figure 1: Landscape interpretation scheme. Source: G. Aponte.

Perception plays as the starting point of a dialog between human beings and the other parts of nature that ends up in a built environment. I say the “other parts of nature” because humans are as nature as a plant or a bird. Although this principle widely recognized by indigenous peoples from many places of the world, nowadays is usually forgotten. One important difference with the rest of nature is that humans want to see their thoughts reflected on those other parts of nature, sometimes imposing it, without regard to what nature actually is. Such an attitude carries the risk of nature capriciously violated as the result of a selfish and unappropriated happiness search.

Although the term biodiversity is new, with no more than thirty years of literary use since W. G. Rosen (1985) and E.O. Wilson (1988) put it in well known writings, the fact itself and its impact in people’s life has been there forever. It is not just variations of flora and fauna as it is usually understood, but of all life expressions and needs. Biodiversity depends on many other natural not alive diversity factors, nevertheless dynamic, such as landform and water.

Figure 2. Well preserved biodiversity in the middle of a big city. The Pedregal reserve in UNAM, México. Photo: G. Aponte

Considering people as another ingredient of biodiversity, together with their culture as one more characteristic of human diversity, the three factors of landscape appear again.

Biodiversity in urban environments has to be much more than “use” or “inclusion” of species of flora and fauna. Urban biodiversity starts with the recognition of all its types of local expressions, starting from the very base. It means the attention to elements of natural support to the “bio” development: those that propel, stimulate, and let native variety develop and, as a consequence, support biodiversity.

Urban biodiversity also considers people a “bio” component: diverse community groups, diverse age groups, that establish different types relations with the place and its components.

Figure 3. Stimulated tropical biodiversity in Marina Bay Sands. Singapore. Photo G. Aponte

What I have promoted in professional and academic practice is the discovery of actual existing nature, first from the sensible and perceptional approach to re-activate feelings, to experience the psychological welcoming provided by natural diversity, then compare those with scientific registers: to validate—in our usual occidental way of knowledge—their native origin or their good behavior as introduced material. In this matter it is important to be open but not too much, to accept introduced species but in reasonable proportion to maintain local identity.

Finally, design responds to the integration in equilibrium for better experiences for people. It means to provide pleasant spaces, inspiration for connivance, and promote happiness for people, based on human’s ethological needs of being involved in a natural world (i.e., biophilia).

The preservation of as much as biodiversity and well connected ecological nets trough city is one of landscape architect’s responsibilities. To select abundant species and biological associations is not enough to design with biodiversity and for people. We must satisfy human scale spaces and habitat. Spontaneous or manipulated, landscape nurtures people’s spirit, and a biodiversity based urban landscape undoubtedly will bring happiness to inhabitants.

about the writer

Maria E Ignatieva

Maria is working on the investigation of different urban ecosystems and developing principles of ecological design. Her latest FORMAS project in Sweden was dedicated to the lawn as cultural and ecological phenomenon and symbol of globalization.

Maria Ignatieva

Local biodiversity as well as urban non-native biodiversity can become a new design tool, even a key to creating a new generation of landscape design compositions that are sustainable, memorable, and at the same time accepted by people.

I started my career as an educator and a consultant in landscape architecture and urban ecology in St. Petersburg, the most European city in Russia. St. Petersburg is the UNESCO Heritage site with numerous historic parks and gardens. For me, urban biodiversity at that time meant first of all spontaneous vascular plants, which found the refuge in bosquets and parterres, manicured lawns and even in the cracks of granite embankments. I remember how happy I was to find rare orchids and ferns just in the very heart of St. Petersburg in the Summer Garden. In mid-1990s, my understanding of urban biodiversity was pretty much European, mostly related to the German School of Urban Ecology. The main task of the new science of urban ecology was to find, describe, and understand urban plants and their associated plant communities, as well as to look for analogues within the surrounding natural ecosystems (urban biotopes and their analogies in nature). Interestingly enough, my dual nature of an urban ecologist and landscape architect (garden historian) directed me to the strategy of protecting rare plants and spontaneous nature even when it contradicted the main strategy of restoration of historic gardens and management policy aiming to keep the manicured and tidy heritage of landscape architecture.

By the end of the 20th century, biodiversity was understood as biodiversity of native ecosystems. There were so many unexplored nearby forests and meadows, bogs and mountain vegetation in Russia, so why should botanists or ecologists be bothered to investigate unusual, complicated urban biotopes and try to think about the diversity of species next to apartment blocks or “dirty” unpleasant industrial zones?

The real understanding and re-evaluation of urban biodiversity came to me only after living and visiting different countries. Without problems, I can recognise lawn or hedge species and park vegetation in New York City and Christchurch (New Zealand). However, these were familiar to me from childhood — urban plant pallets were all foreign here and had no analogues in the surrounding native ecosystems. So I discovered a new term, “native biodiversity” (native urban biodiversity), which is actually quite absurd from an ecological point of view. However, particularly in New Zealand, this native biodiversity term was a necessity. Island ecosystems are very vulnerable to many of introduced “familiar” urban plants. Thousands of exotic plants escaped from cultivation. Here in New Zealand it became extremely clear that me and my landscape architecture peers are responsible for making our urban environment so similar, so uniform. Here in New Zealand I had to switch my urban ecology “eyes” from passive “contemplation” that described urban plant species towards a new understanding of the truly complex character of plant communities. My landscape architecture eyes were in search for inspiration from the extremely diverse native and local biodiversity. Now I introduced a new term to my vocabulary: “urban biodiversity and design. Local biodiversity as well as urban non-native biodiversity can become a new design tool, even a key to creating a new generation of landscape design compositions that are sustainable, memorable, and at the same time accepted by people.

My latest urban destination is Perth, in West Australia. Here I realise how difficult is to design with native biodiversity and try to mimic natural processes in urban environment because of a very limited experimental works. Compared to the centuries of garden design and exploring new varieties of plants, landscape architects have a very limited knowledge of how to marry design with nature and native plants in urban environments.

about the writer

Diana Wiesner

Diana Wiesner, activist, architect, and landscape designer based in Bogotá, is recognized for her leadership in socio-ecological issues and innovative approaches to urban ecology and landscape architecture. Founder of her own practice and director of Fundación Cerros de Bogotá, she promotes environmental awareness, citizen participation, and preservation of natural systems.

Diana Wiesner

To democratize the concept of biodiversity let’s talk about the earth and the forms of life that dwell on it; about how human beings fit in; about the magic and poetry of biodiversity; by listening to people as they share their knowledge of nature.

After finishing my general architecture studies, I began working in the specialized field of landscape architecture. My ensuing research and newfound interests have allowed me to go down a poetic path that leads through nature, high and folk culture, ecology and community affairs. My professional endeavors have branched out into the interrelated fields of biology, art, geography, conservation, hydraulics, hydrology and sociology.

En español.

Intuition and common sense correlate the term biodiversity to biological life and diversity; to the entire, complex system of relationships among living beings, one that recognizes their uniqueness as well as their differences. As a landscape architect acquires professional experience, she or he comes into direct contact with this concept and uses it as a way to understand the interrelated worlds of flora and fauna with other biological systems, including those of water, soil, air.

Subsequently, on a variety of levels, the practicing landscape architect begins to understand how evolution and biological change have occurred within a specific geographical context. Furthermore, biodiversity also involves human beings in this web of biological relationships that can be both tangible and intangible.

In Colombia, the modern phenomena of sprawling urban areas combined with booming population growth have brought constant changes in the configuration of the landscape, as well as in the dynamics of urban ecosystems.

Consequently, it has become increasingly clear that landscape design should be based upon biodiversity, so as to ensure society’s well-being and sustainable development.

The accelerated growth of cities and “the massive and chaotic occupation of territories results in natural spaces becoming insularized and the consequent loss of their biodiversity”.1 In urban areas, the fragmentation of natural landscapes, where vegetation is restrained, leads to their homogenization and reduces their impact on biodiversity.

In addition to this fragmentation, other urban development processes have had a significant impact on ecosystems and their biodiversity. These include repetitive formulas for constructing public spaces (for example, laying out monotonous grids on irregular topography), homogenizing the landscape, and expanding suburbs and conurbation.

Therefore, it is essential that the concept of biodiversity be included in landscape guidelines so that green spaces and corridors can be woven into urban territories. Such guidelines should be in line with public policies that aim to create resilient and sustainable cities.

It is possible to achieve connectivity in urban areas and to preserve and construct green zones when environmental restoration encompasses both the restitution of flora and urban tree planting. Hopefully, all of these endeavors can be carried out hand in hand with local residents.

It is common to hear both experts and the general public refer to “A natural setting in a city”. However, a more apt term would be “A city in a natural setting”. This reversal of priorities would make it easier not only for urban dwellers to understand the importance of biodiversity, but would also help to clarify the need to rationalize growth in accordance with environmental standards.

Biodiversity can be described as a global system in which living organisms are placed and in which their relationships to humankind are defined. In order to help everyday urban dwellers better comprehend this complex, interdependent network, their attention should be drawn to the cracks in the pavement where they place their feet innumerable times, night and day, and where, in their words, “noxious weeds” are growing. These city dwellers should be encouraged to exchange the term “weeds” for “friendly greens”, since these humble plants bring a multitude of benefits to their urban lives.

The term biodiversity can be understood by any number of definitions available to experts. The Convention of Biological Diversity (CBD,1992) defines it as, “the variability among living organisms from all sources including, inter alia, terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems”.2

Because this definition may seem complicated to the general reader, as I have pointed out elsewhere, it, and other similar concepts, should be democratized by taking it out of the exclusive domains of scientists and making it more easily available to local communities.3

The best way to democratize the concept of biodiversity is by simply talking about the earth and the forms of life that dwell on it, as well as about how human beings fit in; by talking about the magic and poetry of biodiversity; by listening to country people and common people as they share their knowledge of nature. Landscape architects work directly with life, and we hear these stories before we intervene in a given space; which is why the idea of biodiversity was surely imprinted in our DNA long before we were given these long, complex definitions to deal with.

Notes:

1 —Wiesner, D. (2015). Democratizing sustainability conversations. En The Nature of Cities. From https://www.thenatureofcities.com/2015/11/29/conversations-on-sustainability-must-be-democratized-towards-soul-resilience/

2 — The Convention of Biological Diversity, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (1992).

3 — Special Plan for Environmental Sustainability Indicators for Urban Growth in Seville. (2007) Office of the Mayor, Seville, Spain

Biodiversidad y «malezas» urbanas

Para democratizar el concepto de biodiversidad, hablemos de la tierra y las formas de vida que la habitan; sobre cómo encajan los seres humanos; sobre la magia y la poesía de la biodiversidad; Escuchando a las personas mientras comparten su conocimiento de la naturaleza.

La intuición y el sentido común relacionan la palabra biodiversidad con vida y diversidad biológica, con todo el sistema complejo de relaciones entre los seres vivos, reconociendo su particularidad y su diferencia. Cuando un arquitecto paisajista inicia las actividades que le dan experiencia, la asociación directa con este concepto lo lleva a entender el mundo florístico, asociado con el mundo animal y con otros sistemas: el agua, el suelo, el aire. Este profesional entiende la evolución y los cambios de una geografía particular en diversas escalas. La biodiversidad involucra al ser humano en ese sistema de relaciones que pueden ser tangibles o intangibles.

Un diseñador de temas urbanos y de paisaje no solo debe pensar en embellecer los entornos; en un país geográficamente diverso como Colombia, es necesario tener en mente compromisos como hacer aportes a la disminución de la pobreza y la desigualdad, aumentar la calidad de la educación y promover el respeto de los derechos humanos. Aunque estos son retos evidentes, la variable ambiental no lo es tanto en las prioridades políticas. El diseñador de paisaje debe utilizar las herramientas que lo apoyen en la búsqueda de un cambio social y ecológico que lo acerque a estos objetivos.

En ese orden de ideas, el diseño de paisaje debe estar estructurado sobre la base de la biodiversidad como fundamento del bienestar humano y del desarrollo sostenible.Fenómenos como la expansión de áreas urbanas y el crecimiento de la población de manera exponencial han generado cambios progresivos en la configuración del paisaje y en todas las dinámicas ecosistémicas de los ámbitos urbanos.

El crecimiento acelerado de la ciudad y «la ocupación masiva del territorio de forma dispersa conlleva la insularización de los espacios naturales con la consiguiente pérdida de biodiversidad». La fragmentación del paisaje y el uso limitado de la vegetación en áreas urbanas tiende a homogenizar y a limitar el aporte a la biodiversidad.

Otros procesos urbanos que, además de la fragmentación, tienen efectos relevantes sobre la biodiversidad y los ecosistemas son las fórmulas repetitivas de solución en el espacio público (por ejemplo, cuadrículas continuas sobre geografías irregulares), la homogeneización del paisaje, los procesos de periurbanización y la conurbación.

El concepto de biodiversidad hace parte de los lineamientos en los que se basa la red de espacios y corredores que conducen los procesos ecológicos esenciales a través del territorio en una ciudad, en concordancia con los objetivos públicos de promover ciudades resilientes y sostenibles.

En las áreas urbanas es posible la conectividad a través de las zonas verdes y protegidas en las que se pueden proponer acciones de restauración ecológica, revegetalización y arboricultura urbana. Todas ellas, ojalá acompañadas por la ciudadanía.

Generalmente se habla de naturaleza en la ciudad, en lugar de entender que la ciudad está en la naturaleza. Esta comprensión invertiría las prioridades, y, de esta manera, la biodiversidad lograría ocupar, en la mente de los ciudadanos, el lugar estructurante que le corresponde en el ordenamiento territorial.

En tanto que la biodiversidad es un sistema de organización de organismos vivos en la Tierra, claramente relacionada con el hombre, se pueden presentar a los ciudadanos comunes hechos que son cotidianos para ellos. Por ejemplo, podríamos señalar una grieta en el pavimento llena de plantas que denominamos «malezas» cuando en realidad deberían llamarse «buenezas», por todos los servicios que prestan; sin embargo, diariamente las pisoteamos o las valoramos peyorativamente. Este sería un buen ejemplo de biodiversidad urbana mal entendida por la mayoría de los ciudadanos.

El concepto de biodiversidad puede tener numerosos significados entre profesionales. El Convenio sobre la Diversidad Biológica (CDB, 1992) la define como «la variabilidad de organismos vivos de cualquier fuente, incluidos, entre otras cosas, los ecosistemas terrestres y marinos y otros ecosistemas acuáticos y los complejos ecológicos de los que forman parte; comprende la diversidad dentro de cada especie, entre las especies y de los ecosistemas».

Esta definición puede ser compleja para un ciudadano común, por eso, como lo mencioné en otro artículo , es necesario democratizar los conceptos que alejan a los científicos, encerrados en sus centros de investigación, de las comunidades.

Una forma de democratizar el concepto sería simple: hablar de la vida en la Tierra y sus relaciones, incluyendo la forma como el hombre se relaciona con ella, hablando de su poética y su magia, escuchando las voces de los campesinos y de la gente del común cuando se refieren a todas las formas y expresiones de vida. Por eso, en mis proyectos tambien diseño grietas donde caben las “buenezas”, las yerbas espontáneas como pequeños brillos de biodiversidad en medio del asfalto.2

Los arquitectos del paisaje trabajamos con la vida y escuchamos las historias sobre ella para intervenir un lugar, por tanto, ya tenemos incorporado el concepto de biodiversidad en nuestro ADN, seguramente mucho antes de acceder a la definición compleja.3

about the writer

Victoria Marshall

Victoria Marshall’s design practice is called Till Design. She is a registered landscape architect and is trained in both landscape architecture and urban design. Marshall is currently a President’s Graduate Fellow at the National University of Singapore where she is pursuing a PhD in the Department of Geography.

Victoria Marshall

I wonder if landscape architecture has over-focused on biodiversity and neglected ecology. Might landscape architecture look into the puzzles raised by other ecology questions in order to tackle the “grand challenges” in the emerging field of urban ecology.

I have raised the topic of critique here so that the relationship between biodiversity and landscape architecture might be looked at more broadly, and as something that is still being formed. I do this because I have struggled with “biodiversity”, as I find it abstract. I share below how I get around this concern by briefly noting something about my own design and research practice, and showing where I fit biodiversity in.

I see close connections between biodiversity and landscape ecology, and I see that landscape architecture has formed a close relationship with landscape ecology. While there is room for landscape architecture to keep focusing deeper into the biodiversity research questions that come with landscape ecology, such as habitat or land-use types as well as, species community and gene issues, and more (Botzat, Fischer & Kowarik, 2016), ecology offers more than biodiversity. For example, I have undertaken collaborative research in urban design and urban ecology about land classification. I wonder if landscape architecture has over-focused on biodiversity and neglected ecology. Might landscape architecture look into the puzzles raised by other ecology questions in order to tackle the “grand challenges” in the emerging field of urban ecology (Pataki, 2015)?

Second, there is the big topic of the cultural characteristics of Nature. Stakes in conservation and change are always formed from a special mix of society and environment, as well as belief practices and institutions. Landscape architecture practices can support, mediate, or resist, such subjectivities. My current research is in the field of geography and it is a study of the “lived ecologies” of peri-urban Kolkata as political ecologies, as landscape, and as a dynamic biophysical spatiality. I do this, in part, with the hope that ecological research questions, such as those that come from biodiversity work, might be asked of this understudied condition in Asia. That is, while I do not measure biodiversity effects, I hope that my research work lays a foundation for applied and research ecology practices that support such urban-rural systems.

I toggle between these approaches. That is, between a critical engagement with urban ecology tools and work that aims to inform what, and where, urban ecology questions are asked. My tangible, biodiversity inflected, landscape architecture is therefore, a creative practice of locating the ”design element” within the ways that I collaborate and co-create with science and society. I believe that my approaches, and others, do work to keep the field of landscape architecture, and others, continuously open. This is important because a diversity of practices might sustain an agile responsiveness to the novel conditions and situations designers, scientists, and researchers inevitably find themselves in today.

References:

Botzat, A., Fischer, L. K., & Kowarik, I. (2016). Unexploited opportunities in understanding liveable and biodiverse cities. A review on urban biodiversity perception and valuation. Global Environmental Change, 39, 220–233.

Pataki, D. E. (2015). Grand challenges in urban ecology. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 3.

about the writer

Mohan Rao

Mohan S Rao, an Environmental Design & Landscape Architecture professional, is the principal designer of the leading multi-disciplinary consultancy practice, Integrated Design (INDÉ), based in Bangalore, India

Mohan Rao

While deploying endemic species is preferred to exotics as a pure aspiration or goal, there are times when a designer needs to take a more nuanced stand on “biodiversity” based on the social, economic, and ecological contexts together.

My practice covers a fairly large diversity, in geographical, social, economic, and cultural contexts. And my interpretation (not meaning or definition) of the term biodiversity varies substantially in response to a combination of such contexts. It is useful to unpack some of these contexts to explore possible ways in which one could deal with biodiversity.

In an ecologically oriented intervention, I interpret biodiversity (referring to vegetation in this note) in fairly strict terms. It would include origin (whether endemic or not), habitat (as understory, relationship with other specimens, etc.), position in the succession order (whether they are pioneer species, for example), ecological function (nitrogen fixing, essential food for fauna, etc) and so on. More importantly, its relevance to other biotic systems and consequent impacts would be more carefully understood.

In an ecologically sensitive context, I interpret biodiversity in fairly strict terms. This would include exclusive use of endemic species and integration of their key ecological functions (nitrogen fixation, as a habitat for avifauna, etc.) in the landscape structure. Equally important is understanding their relevance to other biotic systems such as soil chemistry, ground water regime, etc.

In one particular instance, a recreational development close to a wildlife corridor meant that we had to ensure the complete absence of several species whose flowering and fruiting characteristics are known to excite the elephants which frequent the corridor!! Though all these species were indigenous to the region and have specific ecological benefits, the choice had to be made based on safety issues.

Dealing with the ecological context is relatively simpler compared to the challenges of addressing the issue of biodiversity in specific social and cultural contexts. In creating social spaces, ecological characteristics become less critical than aspirational aspects of the vegetation palette. In the South Asian context, for instance, this means confronting quite of a lot of baggage carefully handed down from the colonial era when designed landscapes signified power, exclusion and domination—characteristics deeply rooted in the visual language of even current day public space design. Given this historic baggage, most public spaces are “expected” to be formal in nature; populated with Roystonea regia or Cupress macrophylla and of course, hedges of Duranta goldiana enclosing formal lawns.

In such contexts, rather than focus on what is truly indigenous, I often choose the middle path of what is not overtly invasive. Many specimens, while clearly exotic, may not necessarily be aggressive or invasive; one could say they are comparatively benign. As long as their impact on other biodiversity—floral, faunal, and avian—including soil and water regime is clearly understood, the conflict between use of endemic versus the exotic can be handled more sensitively.

Such an approach has helped address the ecological aspect (to a lesser extent) and the social dimension of the space created in a fairly balanced manner.

The challenge gets more extreme when dealing with productive landscapes; especially those meant to provide for nutritional and food security.

For example, in interventions around the flood plains of a river that are also the commons for the informal settlements that surround it, the choice of vegetation catering to the food, fuel, and fodder requirements for the underprivileged needs an extremely careful assessment.

Exotic and invasive species are often specimens of choice in such situations due to their faster growth rates.

However, the negative impacts of such choices even over periods as short as three to five years, can be quite drastic in terms of changes to the soil and water regimes.

The inherent requirements of exotic species, such as additional fertilizers, pesticides, increased water demand, soil management, etc., imposes an increased economic burden on the users.

The choice would then get limited to the indigenous palette—they are hardy, resilient to pests and extreme weather and more amenable for multiple canopy structures. While it may seem fairly obvious to the professional, the decision to pursue the indigenous route needs extended engagement with the users to debate short-term efficiency versus long-term sustainability. In this instance, though the choice of vegetation used is clearly driven by their endemic nature, it’s not the ecological paradigm that is driving design decisions, but economic and social frameworks defined by the users.

While deploying endemic species is preferred to exotics as a pure aspiration or goal, there are times when a designer will need to take a more nuanced stand on the issue based on the social, economic, and ecological contexts together.

about the writer

Daniel Phillips

Daniel Phillips is an urban ecologist and landscape architect. He is the co-founder of COMMONStudio, a collaborative creative practice with independent projects and research spanning many countries.

Daniel Phillips

In order to better shape urban biodiversity, let’s reconceive the possibilities it already holds!

The definition of biodiversity in the city is necessarily hard to pin down, precisely because the value and role of biodiversity in cities is open to so much debate and nuance.

Landscape architects often rely on distillations of broad ecological principles to inform design decisions. The promotion and preservation of biodiversity is a great example of how established scientific knowledge can be applied as a useful heuristic device to inform decisions such as plant selection. Biodiversity is understood by many practitioners and managers as shorthand for “complexity”, and more complex ecosystems tend to be more resilient. It’s the same heuristic that we often apply to investment portfolios: The more diverse, the better.

Yet, borrowed as it is from the field of conservation biology (which has historically focused on “pristine” ecosystems), conventional biodiversity principals certainly don’t make a seamless transition onto the urban environments where landscape architects do the majority of their work. Cities are highly disturbed and irrevocably altered environments with compacted, under/over-fertilized soils, vast impervious surfaces, heat islands, and widespread contamination. Beyond these novel biotic and abiotic conditions, the cultural landscape of cities vibrates with the friction of competing values and needs.

It’s clear that the definition of biodiversity in the city is necessarily hard to pin down, precisely because the value and role of biodiversity in cities is open to so much debate and nuance. Urban environments are among the most complex and fascinating ecosystems ever produced, and they surely deserve their own distinct modes of rigorous inquiry to drive new theories and practice. Should we value overall species counts? Functional traits? Presence of Keystone species? Preservation of functional patches and corridors through urban gradients? Of course, it always depends on a host of other requirements and considerations.

One problem is that achieving “biodiversity by design”—the intentional planting of specific species in highly constructed environments—is that it tends to focus on assemblages that can be imposed and managed by official sanction, while ignoring those that arise spontaneously as unwanted noise. But what if some of the plants we’re so quick to erase as “weeds” are actually performing vital regulating, supporting, provisioning, or cultural ecosystem services for free? Does it make sense to replace them for those that can only thrive with constant inputs of resources and maintenance? It’s here that a blind insistence on narrow notions of nativism, and the fetishization of corrective ecologies with the “right” species, only blunts our agency and keeps us focused on the past. Luckily, a growing body of urban ecology research offers a way out of these conceptual traps while offering a crucial reframing of the question at hand: What might cities already be trying to tell us about their own emergent patterns of biodiversity?

The “Global Urbarium”

Commonstudio’s “Global Urbarium” is our unfolding multi-city survey of spontaneous urban vegetation that seeks to highlight and understand the subliminal forms of natural process that occur in our cities. It draws on methods of citizen science, herbarium collection, and field ecology with intended applications for designers and managers. To date, the project has explored diverse urban contexts from Los Angeles to Rome, Budapest, and Bangalore. The most recent iteration of the Global Urbarium aims to understand the common plants which define post-industrial cities of the midwest. It focuses on four so-called “legacy” cities: Detroit, Pontiac, Flint, and Saginaw. These sites roughly constitute a post-industrial corridor of inquiry, travelling in a northwestern transect across the “Thumb” of Michigan. Aided with a grant from the Graham Sustainability Institute, the Rustbelt Herbarium is the most ambitious of these efforts to date and the first of its kind in the region.

Some of the plants we find in our sampling sites are hardy natives, others escapees or remnants of local gardens. Others are common “pan-global” weeds that we’ve encountered in many other cities around the world. Some are buzzing with pollinators or teeming with invertebrate life, or rooted proudly in the mouldering rubble of an abandoned factories. We try not to judge, but to merely observe, collect, and take detailed notes. In addition to a publicly facing digital herbarium available on Instagram, we are building a database which will serve as a foundation for inform future studies, comparative analysis, and interdisciplinary tools. Our ultimate goal is to make this data actionable to researchers and practitioners who may be interested in incorporating these messy features of the urban ecosystem into their purview and projects.

For too long, urban ecosystems have been subject to a strange mode of “double blackmail”—too urbane for naturalists to take seriously, and too wild for urbanists to sanction. It’s clear that cities are already way more biodiverse than we had imagined. But if we want to better shape urban biodiversity by design, we would do well to study it’s nuances and messy complexities in more intentional ways.

about the writer

Yun Hye HWANG

Yun Hye Hwang is an accredited landscape architect in Singapore, an Associate Professor in MLA and currently serves as the Programme Director for BLA. Her research speculates on emerging demands of landscapes in the Asian equatorial urban context by exploring sustainable landscape management, the multifunctional role of urban landscapes, and ecological design strategies for high-density Asian cities.

Yun Hye Hwang

Beyond promoting an abundance of species, designers could strengthen the concept of biodiversity in design by understanding the principles of urban ecology aiming at habitat enhancement.

- Utilizing naturally growing plants: Singapore’s ecosystem is extremely diverse and structurally complex, as the city state is located in the equatorial zone. But in design practice, plant selection commonly relies on the limited plant species available in the local horticultural industry. In taking advantage of the tropicality, however, designers could explore other alternatives to promote biodiversity. For example, in one garden design project we selectively utilized some of spontaneously growing plants not available in the market but which are not aggressive, are generally well-suited to support local habitats and are tolerant in an urban context (see project photo below).

‘From Lawn to Forest Garden’ project (2017). The enchanted garden in NUS (National University Singapore) campus came naturally by promoting growth of spontaneous vegetation. Photo: Zi En Jonathan YUE - Increasing public acceptance of biodiversity: Urban dwellers are often known to prefer orderly parks with low-diversity greenery. However, they are becoming conscious of nature conservation, suggesting a shift in perception of biodiversity. The challenge is how to improve social acceptance for biodiversity (defined it as living organisms that have structural and genetic heterogeneity and spontaneity to flourish over time). A forthcoming article in JoLA ‘Intended wildness’ exploring design and management strategies to realize an ecological aesthetic and address social acceptance while promoting spontaneous growth for biodiverse green spaces in a tropical compact city expands on this.

- Considering principles of ecology: Beyond promoting an abundance of plant species, designers could strengthen the concept of biodiversity by understanding the principles of urban ecology aiming at habitat enhancement. Design considerations could include larger-scale ecological networks, geological/historic site conditions, interactions between flora and fauna, habitat requirements supporting genetic diversity, microclimate, and functional traits of plants, soil and water. A recent paper identifying actionable design strategies through an ecological lens suggests how biodiversity could be developed in design projects.

- Continuous monitoring process afterwards: Biodiversity is not a static concept but is adaptable over time. Yet this aspect of biodiversity is de-emphasized and underappreciated in contemporary landscape practice. For example, designers are typically responsible only until the completion of a project, as highlighted by Felson. They may pay less attention to the inherent biodiversity of constructed landscapes and over/underestimate their outcomes based on achievement at the time of the construction. In fact, biodiversity may flourish several years later. A mangrove planting project we documented in Manila is a prime example (project photo below).

Baseco Kabalikat Mangrove Project, Manila. After several years of failures due to major typhoons, mangrove patches were established and now attract aquatic fauna. Photo: Yun Hye HWANG

- Interacting with scientists: To address biodiversity, designers should seek out interactions/collaborations with ecologists. Ecologists could provide more concrete theoretical data that contribute to design ideas. For example, they can list target species, suggest habitats that suit the design site, gauge ecological functionality of design proposals, and explain what to do in the frame of urban ecology. For better communication between designers and ecologists, I recently suggested “redefining working scopes” and “creating a more open design process” in the TNOC roundtable, “What ecologists and landscape architects don’t get about each other, but ought to”.

about the writer

Jason King

Jason King is a landscape architect focusing on urban ecology, practicing at GreenWorks, blogging at Landscape+Urbanism, and researching at Hidden Hydrology.

Jason King

Biodiversity

Each site we design, as landscape architects, is an opportunity to increase biodiversity as it works in the local bioregion and bolsters local goals, which collectively contribute to tackling that wicked global problem of biodiversity loss.

A quick look at the Google Ngram shows how little usage the term had prior to the 1980s, which surprised me, until I realized that it is a relatively new portmanteau which locks both biology and diversity (both terms which go way further back in defining ecological science) into a tidy package. Biodiversity has a timelessness, along with a simplicity and coherence makes it a powerful term because of its lack of ambiguity. Many terms borrowed from ecology and science are misunderstood and misused, and as we know, there’s an overabundance of jargon in the world of landscape architecture and design. These terms are employed at times to inform key processes, however can also be used to obfuscate, dumb-down, or greenwash. Biodiversity, however, is a measure, and thus transcends being a buzz-word (with the exception being if you’re actually measuring bees), avoiding jargon status occupied by many other terms used by landscape architects, sustainability, and placemaking.

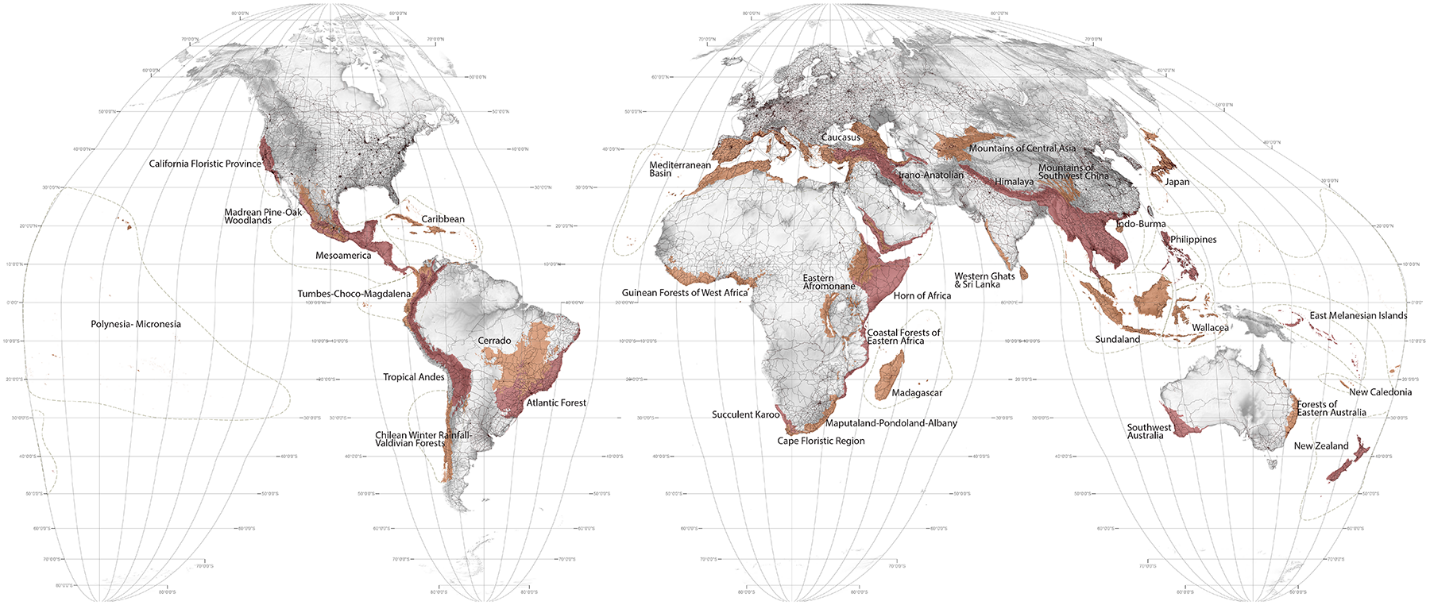

Biodiversity is also engaging, as it is inclusive of larger contexts (global and regional biodiversity) but offers a simple and measurable vehicle for what we can do locally. The global challenges are pointed out in the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, and perhaps more poetically in Richard Weller’s ambitiously engaging Atlas for the End of the World, which showcases critically endangered bioregions, creating “…essential groundwork for the future planning and design of hotspot cities and regions as interdependent ecological and economic systems.”

At a functional level, biodiversity isn’t just about habitat, but can also provide functional ways of ensuring our designs have adaptability and resilience, because we are modeling them. This isn’t about native purism, but acknowledging novel ecosystems that require new assemblages, but using cues from natural reference ecosystems in designing using multiple species, three-dimensional structural canopies, and incorporating species. Modern monocultures may be striking in their formality, but are at risk for shifts of climate, pests, and other issues. This local action to global connection obviously is limited by the scale of the work we do, and there’s only so much that can be accomplished on each site. Thus, landscape architects need to continue expanding our reach and influence beyond site boundaries into policy, planning, and strategy to expand our reach and impact.

By casting a broad net about the component parts, bio- (living organisms) and -diversity (variety), the term is able to be inclusive and also applicable to so many situations. I think of this in terms of ecology, and the shift towards both incorporating humans as key organism into ecological studies allows us move beyond ideas of untouched nature and natural processes, and truly measure human impacts in the Anthropocene. In short, it now shows that humans are intertwined (and culpable) in destruction, and can be important actors in regeneration. The term also hints at a viable metric for equity, which is often hard to measure. We tend to be focused on non-human diversity, but accounting for the full range of species, and how much diversity (of usage, participation). our designs yield. The term is a way of expanding the potential for dialog around regenerative design potential for us as designers, and a key metric for success of these landscape in terms of actual performance.

Last week, like many in Portland, my wife and I ventured up into Northwest to view the annual gathering of the Vaux’s Swifts as they looked to bunk down for the night in the old Chimney at Chapman School. A sideshow twenty years ago, it’s now blossomed into a full spectacle, with thousands of people of all ages and walks of life each year coming to experience the event. While the drama of raptors zooming through the tightening funnel of swifts was accompanied by the oohs and ahhs of the crowds, it showed an important lesson about biodiversity.

By saving the Chimney at the school, we’ve created a place for this unique species to have a home on their annual migration route. By creating a city that is verdant and varied, we create a destination for species, including humans, that are attracted by these unique qualities. And by highlighting a somewhat oddball but magical event to celebrate this, we come together, diverse groups of species, humans and non-humans, exhibiting variety and richness, in a display of true biodiversity.

about the writer

Andrew Grant

Andrew formed Grant Associates in 1997 to explore the emerging frontiers of landscape architecture within sustainable development. He has a fascination with creative ecology and the promotion of quality and innovation in landscape design. Each of his projects responds to the place, its inherent ecology and its people.

Andrew Grant

Designing with Beasts and Senses

‘We are all Bloody Animals…its really weird that with all our technology, with all our instruments, with all our intelligence, still we are really basic.’ – Anthony Gormley, artist

‘We are all Lichens Now’ – Scott F Gilbert, biologist

We are literally a part of the Earth’s living system, and this is where I struggle with some of the conventional landscape architectural approaches to biodiversity that suggest biodiversity is an option, to be embraced or not depending on your point of view.

My body supports a huge diversity of microorganisms. I am biodiverse. I am part of biodiversity.

I am an animal and my habitat is the city of Bath. From here I imagine plans and designs for pockets of land across the world but always have in mind my connection to the species that exist there or could exist there. Biodiversity to me is not a tick box topic to collect points on an environmental accreditation form. Biodiversity is the foundation and inspiration for all my work.

As a designer I look for the potential to enrich a place with diversity of species but also to shape it so humans can co exist and draw inspiration, wonder and joy in the experience of that place. I also think we have a duty to go beyond the confines of our project site boundaries and to join forces with those desperately trying to slow or halt the extinction of species. As Roberto Burle Marx said “it seems to be almost an obligation of the landscape architects to combat destruction and to preserve certain ill fated species in danger of extinction in order that they survive for the education and enjoyment of future generations’’. Roberto Burle Marx Lectures. Landscape as Art and Urbanism. 2018

If our role as landscape architects is to design for the experience of landscape alongside conservation of the natural world then we must start with an understanding that biodiversity underpins the functions of ecosystems on which we depend for our food and fresh water, and provides the resilience and flexibility of the living world as a whole. We are literally a part of this living system and this is where I struggle with some of the conventional landscape architectural approaches to biodiversity that suggest biodiversity is an option, to be embraced or not depending on your particular point of view. McHarg’s Design with Nature, and many of the environmental planning and design tools since, sets “Biodiversity” up as a factor in the design process and often just a factor among many. It becomes a tick box item rather than a fundamental driver and inspirer of the process. E O Wilson’s “Biophilia” is closer to my heart, but its definition—“the idea that humans possess an innate tendency to seek connections with nature and other forms of life”—also implies some form of disconnect or difference between humans and other life forms.

“Beasts and Senses” is a shorthand title for designing with biodiversity and the human experience in mind. It is a title I have used at Grant Associates since I started the practice over 20 years ago and I still keep coming back to it as a prompt for starting each project. Over the years we have applied this in many different ways. At New Islington in Manchester we had the idea of using an image of the very rare Floating Leaved Plantain that existed in the nearby canals, as a motif for the streetscape and developed a grid of large cast iron discs decorated with the motif and thus bringing a sense of this species to the street in a way that enhanced the character and quality of the space.

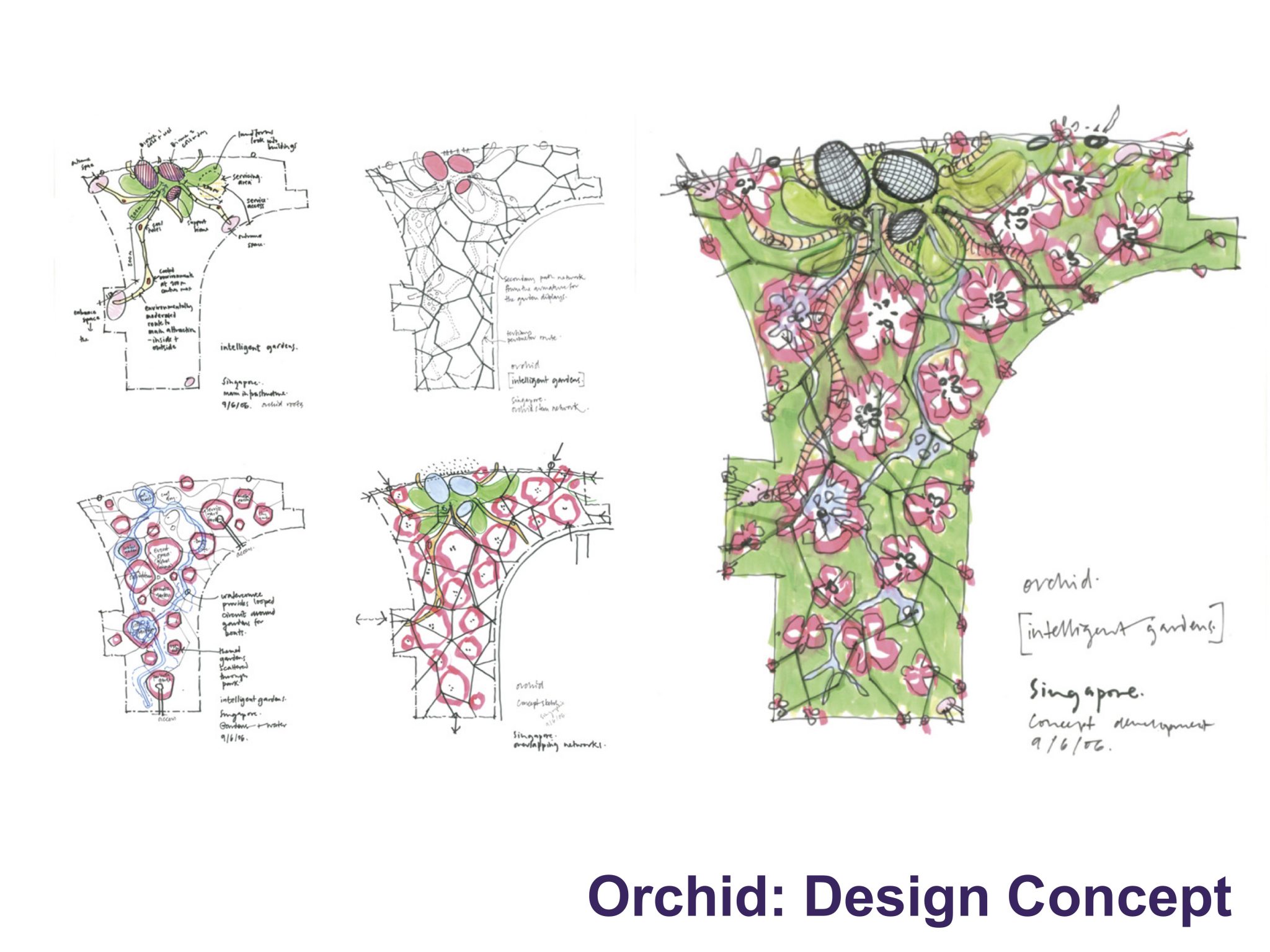

At Gardens by the Bay we used the image of the orchid, Vanda Miss Joaquim var. Agnes, the national flower of Singapore, as a metaphor for the project. This orchid represents the most cosmopolitan species in the world in one of the most cosmopolitan cities. A plant of beauty and intrigue. A plant with an extraordinary physiology that allows it to exist and to remain beautiful, in the harshest epiphytic conditions.

At Gardens by the Bay we used the image of the orchid, Vanda Miss Joaquim var. Agnes, the national flower of Singapore, as a metaphor for the project. This orchid represents the most cosmopolitan species in the world in one of the most cosmopolitan cities. A plant of beauty and intrigue. A plant with an extraordinary physiology that allows it to exist and to remain beautiful, in the harshest epiphytic conditions.

In summary I think these three projects portray my personal approach to biodiversity in design. Celebrate Biodiversity – Create Biodiversity – Conserve Biodiversity. Be an animal!

about the writer

Sylvie Salles

Sylvie (PhD in Urban Studies) is an architect and senior researcher at the Larep (landscape research laboratory) and full professor in landscape architecture at the École Nationale Supérieure de Paysage de Versailles.

Sylvie Salles

A sensitive bio[socio]diversity

The real ambition—to improve biodiversity as bio[socio]diversity—is that biodiversity be part of our landscape experiences, in which landscape architecture focuses on an ecological equilibrium with communities’ interests or wishes.

French landscape architects used to deal with environmental approaches that improve human quality of life; for example, rainwater management of the 70s’ new towns. Thus, in urban design, biodiversity is considered as a link between human ecology and natural process. The attention to the living beings’ diversity is filtered out by an attention to the way people perceive and use their own environment. Here, in the word “biodiversity”, the biologic sense is closely attached to the common sense of “what is our environment”. Design with biodiversity involves a new aesthetic because environmental matters were mainly run by technical approaches, because horticultural processes ran gardening. The French landscape architect, Gilles Clément (http://www.gillesclement.com/), has been a leading figure to disseminate a new landscape and gardening culture; based on the ecological richness of abandoned spaces (Third Landscape), and on the accompaniment of natural processes (Garden in Motion). This culture favors an aesthetic vision, which encouraged urban brownfield and urban wild. These new images of the nature, for townspeople, are also little spots of biodiversity; but they are not connected to form a corridor. .

The real ambition–to improve biodiversity as bio[socio]diversity–is that biodiversity be part of our landscape experiences. The Chevreuse’s Regional National Park, Southwest of Paris, promotes “Landscape and Biodiversity Plans” to combine urban planning; landscape preservation, and biodiversity restoration. It’s a step, where landscape architecture focuses on an ecological equilibrium with communities’ interests or wishes. When I worked on this project, I proposed to involve artists to bring out a sensitive environmental experience, and to help people to center on their own involvement in living processes. It did not happen, because the board assumed that urban planning was a technical matter. They didn’t understand that biodiversity, as a landscape object, articulates material facts—to improve ecosystems— and symbolic values as pleasure, comfort, or beauty. Nowdays, ecology asks us to no longer dissociate ecosystems functionality and human well-being. Sensitive, socio-symbolic, and biophysical qualities of our environments have to interact. That’s enlarged the boundaries of the biological diversity. Biodiversity refers to equilibrium —between social and natural processes— focusing on the ways human and non-human share the same habitat, and, for a landscape architect, on the ways to make visible this common use. For the biologist, Jacob von Uexküll,[4] men and animals have the same kind of relationship with their surrounding environment; based on the perceptions they have and the uses they make. Just as, in landscape architecture, the word “biodiversity” refers to a subjective lived environment. So foster biodiversity is a sensitive act, more than a scientific one.

[1] Grenelle’s Laws for “a national commitment to the environment” set an action framework to address the ecological emergency. One important goal is taking biodiversity into account in urban planning.

[2] Bernard Lassus, The Landscape Approach, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998.

[3] Alain Roger, Court traité du paysage, Paris: Gallimard, 1997.

[4] Jakob von Uexküll, A Foray Into the Worlds of Animals and Humans: With a Theory of Meaning, translated by Joseph D. O’Neil, Minneapolis/London: University of Minnesota Press, 2010 (first edition, 1934).

about the writer

AnaLuisa Artesi

Ana Luisa Artesi is Head and Founder of the studio Ar&A – Arquitectura y Ambiente, an interdisciplinary office, whose focus is on highways, private and public landscapes, individual houses, multi-family buildings and housing developments

Ana Luisa Artesi

In the intervention of landscape architecture projects, we start with biodiversity’s definition as a reference framework, but then move beyond it it, to the characteristics of the place and the environment, developing and re-developing according to changing local necessities.

Diversity

Difference

Micro and Macro

Complexity

Definition

Biodiversity is the variety of living organisms from all ecosystems and ecological complexes of which are they part.

“There are many dimensions of Biodiversity. Every biota can be characterized by its taxonomic, ecological, and genetic diversity and that the way these dimensions of diversity vary over space and time is a key feature of biodiversity. Only a multidimensional assessment of biodiversity can provide insights into the relationship between changes in biodiversity and changes in ecosystem functioning and ecosystem services.”

—Global Assessment Reports of the Millennium Assessment

Biodiversity is everywhere and it is very complex and difficult to appreciate. All ecosystems—managed or unmanaged—are included. Wild lands, reserves and natural areas, but also plantations or cultivated areas, all have their own biodiversity. Every action undertaken by man concerns the maintaining of the ecosystem services. Millions of different species of plants, animals and microorganisms coexist in genuine and adapted ecological niches.

Diversity of genetic systems structures each species and combine in an evolution and constant change. Individuals and communities coexist in territorial and survival struggles, within ecological niches rich in relations and diversity. Diverse natural kingdoms and human society live in urban and suburban environments in an intricate relationship fabric.

Fight

Survival

Necessity

Interdependence

Adaptation

Transformation

Mutation

Science

Awareness

Landscape Architecture

The ecological science can be integrated into landscape architectural projects by taking the concept of biodiversity and its philosophy and understanding ecosystem related to urban necessities.

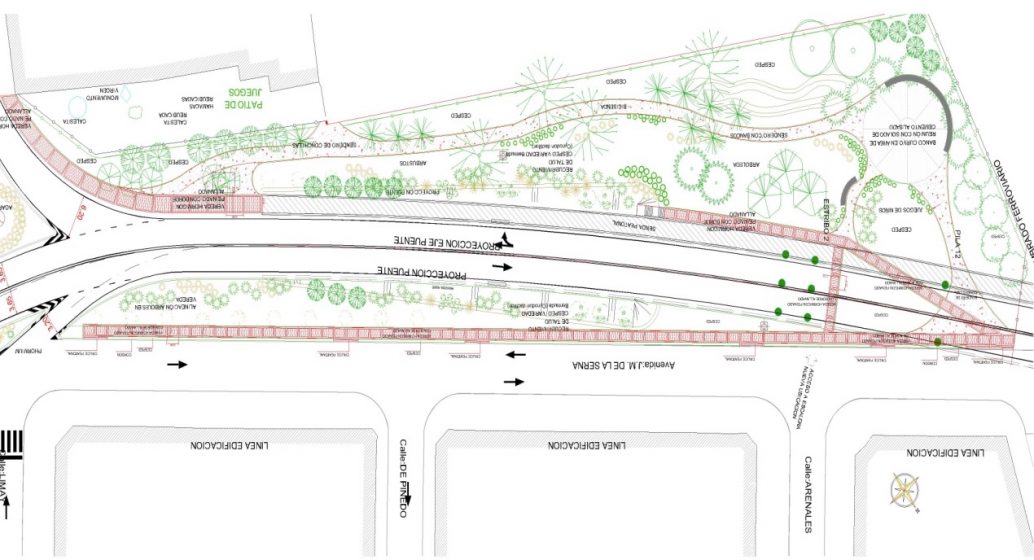

The continuity of the Parks: biodiversity corridors

Teams of landscape architects, ecologists, and researchers in coordination with social actors are needed to implement solutions and creative proposals for urban sustainability and the interaction of people with nature. In the intervention of projects, we start with the definition as a reference framework, which is analyzed according to the characteristics of the place and the environment, and is redeveloped according to changing local necessities.

Design concept is not a repetition of typology, but provides solutions according to the site requirements. The challenge is to recognize the complexity of nature to give appropriate responses.

The growing of Nature in Cities

The presence of man and his activity constitute another part of the local biota—their actions are directly or indirectly reflected in the environment, forming an extensive ecological and biocultural system.

A bridge can be designed as biological or ecological corridor that supports life forms containing plants and associated biodiversity.

Greening trails, edge walks, and groves can be traveled by pedestrians, small vehicles, through a natural landscape, by the margin of a river, or the sea, or a park in the city. These are spaces for life and biodiversity. The interactions of man and fauna, insects and microorganisms that inhabit or travel through these spaces is verified. These spaces provide places for observation, study, and appreciation of individuals.

about the writer

Kevin Sloan

Kevin Sloan, ASLA, RLA is a landscape architect, writer and professor. The work of his professional practice, Kevin Sloan Studio in Dallas, Texas, has been nationally and internationally recognized.

Kevin Sloan

Applied and Synthetic Biodiversity for Cities

Since each urban site cannot support all the species that are possible, the role of biodiversity is to guide the wild life program and synthetically edit the possibilities into a list that will be ecologically successful, appropriate and possible to co-exist with human activity.

But the US cities that have rapidly appeared in the last century — most especially suburban mega cities like Atlanta, Phoenix and Dallas / Fort-Worth, etc. — have given rise to unprecedented problems and environmental challenges. As readers of “The Design of Cities” already know and appreciate, the list of problems and relevant topics is long and seem to multiply as fast as they are identified and remedied with innovation.

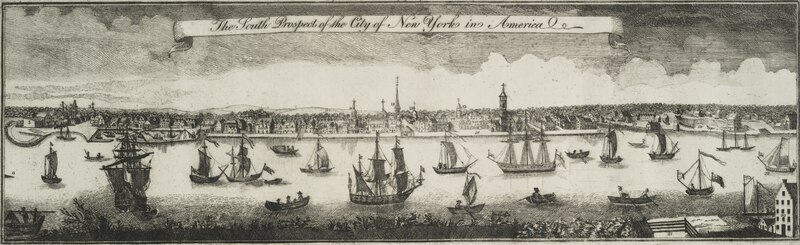

A new way of re-conceiving biodiversity is now possible with the appearance of the new cities, especially since the new urban forms are replete with wildlife. An overview of the contemporary city and how it supports wildlife, versus how the historical city form excluded it, is first.

Prior to the twentieth century the relationship between city and nature was a set pattern of relationships that repeated.

Pre-modern cities were typically dense formations of buildings with spatial networks of streets and public spaces all within a physical boundary. Whether the boundary was a fortification wall or a natural barrier like a river, mountain or the water surrounding an island, the outcome almost always produced an identifiable object — the city or town situated in a landscape. In these cities, being inside or outside the city, was never a geographical matter in question.

Surrounding the city was the “field”. Agriculture, commercial exchange, open visibility for protection against advancing mercenaries were just a few of the roles serviced by this mediating zone. Danger, lawlessness, and predators roamed freely out in the wilderness, which was the final layer beyond the field.

Biodiversity is no longer a concern that is exclusive to wilderness. It is and can be an integral consideration for contemporary cities, since the low density of suburban mega cities offers an abundance of open space where wild life can take hold.

Nature sightings within contemporary cities like Dallas are now commonplace. Once, where only pests and vermin plagued a city like ancient Rome, it is now a privilege and delight to see migrating waxwings in a backyard tree, monarch butterflies in lantana, or to hear the whistling cry of a red tailed hawk overhead. Exterminating the natural life, for whatever reason, is futile. It will only return since the sparse density of a suburban mega city gives nature and us and new kind of opportunity to co-exist.

Where biodiversity was a condition and priority only for environments outside a city, now it can now mean a synthesis of human and natural life in the city.

ReWILDing is sweeping the world. The process of making a ReWILDed landscape begins with the determination of an inventory of wild life that a site can reasonably and appropriately support. This is a task greatly improved with scientists and experts that specialize in biodiversity.

Once the wild life program is established; plants, landforms, and patterns take shape accordingly. Establishing the biodiversity of a ReWILDing program is an inseparable part of this activity. Since each urban site cannot support all the species that are possible, the role of biodiversity is to guide the wild life program and synthetically edit the possibilities into a list that will be ecologically successful, appropriate and possible to co-exist with human activity. Applied incrementally, regions within a suburban mega city will transform patiently, with each new project, to collectively generate a more balanced urban ecology where the built and bio-morphic are synthetically integrated.

I see ReWILDing not as a trend or the latest environmental thing, but rather as the next step for sustainability and a logical final step in making American and especially, sprawling Texas cities unique from our European and colonial predecessors. A new kind of approach and application to biodiversity will help carry both activities, forward.

Leave a Reply