Earthworms can be found in many urban settings from gardens, to football fields, to cracks in the sidewalk where there is some moisture and nutrients. They can be enlisted to bring us closer to the life around us and teach us lessons about survival, nutrient cycles, and reproduction. Any wild animal that thrives the harsh conditions of the city should be praised and studied. Children as well as ecologists can gain insights about their importance in food webs with simple techniques.

Don’t worry. Earthworms don’t have teeth, nor do they transmit disease, so they are entirely safe to handle, if a bit slimy. They are extremely sensitive, able to recognize light, breath through their skin, and feel vibrations. Some earthworms are parthenogenic, meaning they can reproduce without having sex. Others like the nightcrawler (Lumbricus terrestris) are hermaphroditic (have both sexes), and mate by attaching themselves to another worm, impregnate each other, and then have their fertilized egg sacs (the clitellum) migrate from their mid-body over their head where they place it in a good spot for their babes to hatch. One rainy day in the forest I found newly hatched earthworms crawl up to the tip of ferns and watched as they hitched a ride on my pants.

Thank an earthworm

Earthworms are doing a lot of work in the city. They are decomposers and nutrient recyclers. They aerate and mix the soil by creating tunnels and move nutrients and organic matter up and down. They turn leaves and food scraps into soil! Amazingly, they also help process and degrade our toxins. Earthworms have been found to degrade petroleum products, extract heavy metals, and break down PCBs.

Here in Portland once the autumn rains begin and leaves start to drop, worms get to work. The nightcrawler builds small pyramids, called middens, which are a mix of twigs and leaves pulled near their entrance of their underground lair. Their castings (or poop) are easily found nearby between clumps of plants throughout parks and gardens. I sometimes drop leaves around middens in the evening, and in the morning the worms have pulled them closer to their tunnel entrance and often under the surface for a meal.

Children and earthworms

Because earthworms live close by, are creepy, and quite resilient, they are perfect animals for children to learn from. My daughter’s school yard is prime night crawler habitat, as is grandpa’s driveway. Crows know about worms too, as do robins. The crows move in groups slowly and methodically to pull out worms. Other times they turn over leaves on my street harvesting worms. I’ve seen them stash worms on my neighbor’s roof. Robins do a quick short run to find worms in fields.

At school, students can have a pet worm in the classroom by putting one in a jar with soil and leaves, and the kids can watch the worms eat, move, and launder the soil. The mustard extraction method is a crowd pleaser, whereby you mix water with ground mustard seed (found in the spice section) and pour the mixture over the soil. Watch for the next 5 to 10 minutes as worms bubble up out of the ground. It’s like a mild chili bath for the worms, so I usually have some extra water to help wash it off them. This is a great ecology lab or just a fun learning activity.

Earthworms are change agents

Along with the first European cargo to Portland arrived the first European earthworms. Early ships used soil for ballast and would unload it at the port and fill it up with goods. Worms crawled out of the ballast and into our forest, including Portland’s Forest Park, which is adjacent to one of the earliest ports in Portland. Forests in the Midwest and east coast of the US and Canada have well documented shifts of plant and animal communities due to the introduction of earthworms. The soil changes from a fungal dominated, slowly decomposing, layered substrate, to soil that is bacteria dominated with an accelerated nutrient cycle. These changes affect tree composition, habitat quality for birds and amphibians, and have been found to increase drought stress in sugar maples.

Since earthworms are master nutrient recyclers, they also release nutrients that can cause nutrient problems (eutrophication) in waterbodies. This presents a challenge for waterways managers that work to control aquatic algae and macrophytes. Besides all the fertilizer and nutrients humans put into our waterways, what part of eutrophication can be accounted for by earthworms? Oregon does have native worms, unlike the recently glaciated northern latitudes of North America. The lily-scented Oregon Giant Earthworm is the most charismatic. It can grow to over a meter long and burrow up to 4.6 meters but is exceedingly rare. One published earthworm survey in forests just outside of Portland in 2002 had a hope of documenting its presence in sites where it had been previously seen. The authors didn’t find the Giant Earthworm, but they did find on average 1,136 kilograms of earthworms per hectare, over 97% of which are of European origin. That’s the weight equivalent of 2 cows per hectare, that are underground and hungry.

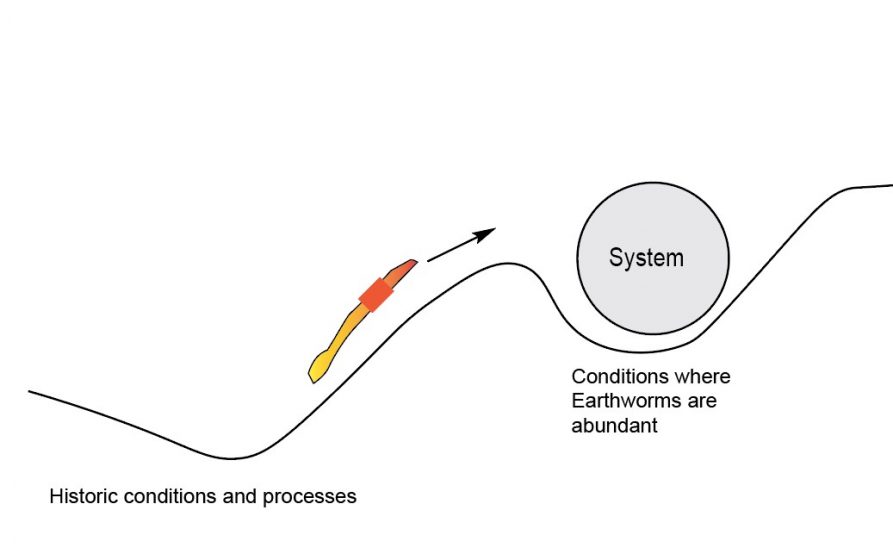

That was the only study I could find from my area, but I wanted to know for myself if this is the case in the sites I manage in Portland. I surveyed using the mustard extraction method and repeated plots in my backyard, and in wetlands and forests. I found them in assorted abundances in different areas the city. A few isolated conifer forests remain earthworm-free, but the highest plots translated to over 800,000 worms per hectare. What conditions do earthworms prefer and how do they shape conditions for plants and animals? We did find a clear correlation between an absent duff layer and abundant earthworms. The duff layer (or the humus layer or Organic horizon) acts like a sponge for water and nutrients. It’s also an important habitat for native seedlings, ground fauna (like salamanders), and a hotbed for mycorrhizae. The worms, which can hasten its disappearance, create a driving force that shifts plant and animal communities. Plants that thrive on soil disturbance (you know, weeds), do well with earthworms, and plants that need stable soils with a deep duff layer often disappear. We’ve seen this shift in Portland, much like elsewhere, whereby graminoids (grasses and sedges) and certain weeds (garlic mustard and herb Robert) are favored by earthworm presence. Other understory plants found in nearby old growth forests can’t handle the conditions that worms create. Like other newly arrived species that have a large biomass, earthworms form new connections with resident wildlife. Beyond the birds I mentioned, moles, voles, frogs, salamanders, and even raccoons and turtles eat earthworms.

Urban natural areas have lots of stressors: climate change, urbanization, the urban heat island effect, fragmentation, pollution, and hydrological changes. These stressors, however, are often impalpable. Worms are a living stressor that can be counted and held. You can witness their effects once you train your eyes and hands to them.

The more I study earthworms (and read earthworm studies), the more I realize their silent and continuous labor has deep imprints in the ecology around us. There currently is no field guide or even technical manual to identify earthworms of the west coast of North America. But with this absence of the basic taxonomy of earthworms, there is an opportunity for us to learn about them and observe and document their effects on the world around us. Their ability to thrive in adverse urban conditions generates the need for humans to collaborate with them to create sustainable landscapes. Their ability to degrade human pathogens has been investigated for use in composting facilities and sewage treatment plants.

Earthworms are just outside your door waiting to be discovered (if you live in a temperate wet climate). If you can’t find worms, there are ants and spiders and millipedes and flies and beetles that can be observed nearby. A few might even be new to science. Children should get in on the discoveries: document creatures on iNaturalist or a nature journal, set up experiments and surveys, and get their hands dirty. Worms have shifted my perspective about the complex nature of cities, underground. With their introduction, our forests here are playing by new rules. Earthworms are a major driving force behind shifts in the plant, animal, fungal, and bacterial communities.

How do we learn about changes taking place in our cities? Kneeling and examining the soil and its creatures is a good start. We can learn about the life around us, and how resilient it can be. Worms can be a conduit to noticing the myriad of ways of how other creatures (as strange as they might be) are connected to how we treat our cities. Most people love some aspect of a city’s nature, but if we can all take some time and observe how everything is interconnected, then there is hope for a just and green world.

Toby Query

Portland

A lovely article ‘INDEED’

A lovely article. Your final point should be engraved everywhere:

“if we can all take some time and observe how everything is interconnected, then there is hope for a just and green world.”

Incidentally, compost heaps are also a good place to find earthworms relatively easily.

Hi James,

Thanks for the comment. That is fascinating. I’ve heard other stories of people trying to capture them and getting pulled to the ground from their strength. Do you have any pictures? And how are you planning on establishing a new colony? I assume they have many requirements that people can’t quite understand. Worms, and most all soil organisms, are such a mystery, but I’m super interested in what you discovering. Thanks!

Toby

Toby, We have “giant” native earthworms here in western Oregon. I have found some as long as 24 inches in the coastal mountains near the old town of Valsetz and I am currently attempting to establish a colony of the giants in my back yard here in Dallas (west of Salem). I have sent specimens to scientists for identification and have a few photos. If the conditions are good I’ll collect more soon. I thought you’d be interested.