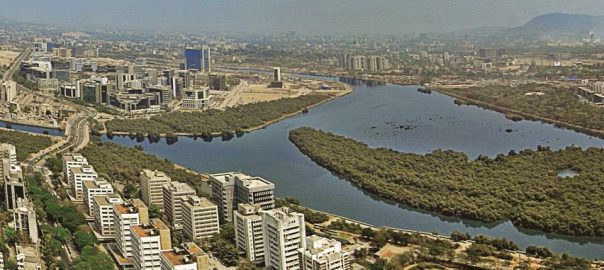

There is a surprisingly common contradiction hidden within centers and scattered along critical edges of the most diverse cities around the world: abandoned and obsolescent industrial structures. This is the narrative of one such place, grounded in its complex natural and industrial history, suspended for a moment in the center of a transforming community in the heart of a growing global city.

From the vibrant centers of expanding cities, to crumbling relics of former metropolitan centers, lurk massive and abandoned industrial architecture, structures, and artifacts. Along waterfronts, former railway lines, pressed up against highways, tracing the gaps between divided communities, we can find the detritus of a former industrial urban revolution. These are the architecture and artifacts that once drove the massive growth of cities in the industrial era, that time of extraordinary expansion from the 19th through the mid 20thcentury. These structures fueled and transformed urban expansion around the world, encouraging abrupt enormities of scale, a repetition and growth of urban form previously unprecedented in human history. Many of these complexes and structures remain but today are decrepit, polluted, underutilized, or simply abandoned, facing imminent destruction.

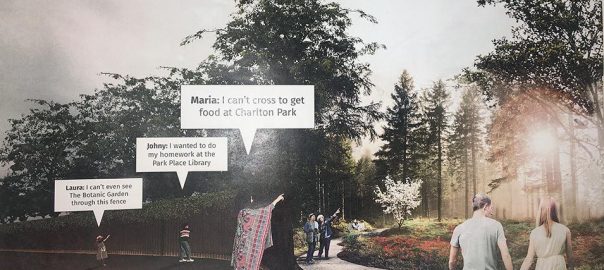

These former industrial sites pose one of the great urban challenges and opportunities for the early 21stcentury. In this time of the ascendancy of cities around the world, how can we address the urgent challenges that industrial scale helped to create? And how do these ruined former industrial collections of buildings offer particular opportunities on an unprecedented scale to address the current needs of our cities: greater equity, access to green spaces, habitat restoration, and the need to address resiliency in a time of profound climate change? The former industrial Brooklyn waterfront is one place that brings all these challenges together.

We were waiting in a green room in the heart of Manhattan, backstage at The Municipal Art Society Summit. At this conference dedicated to urban innovation, I was presenting our designs to encourage greater equity at Halletts Point, a waterfront community combining mixed-income housing, public schools, green infrastructure, and resilient multi-level waterfront park. Seated next to me were two young women in their early 30s, Stacey Anderson and Karen Zabarsky, who had just presented their idea for a new kind of waterfront community green space named “Maker Park”. Their idea grew out of a previous innovative plan for the Brooklyn waterfront, which had partly gone wrong.

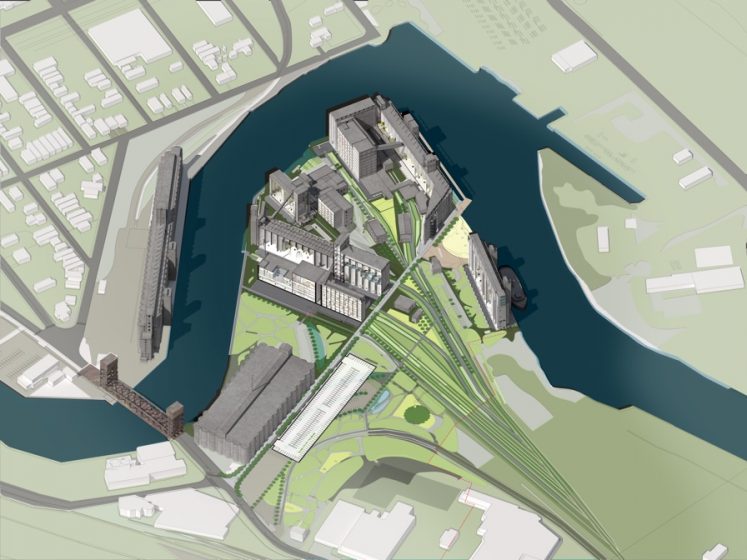

In 2005, when New York City rezoned the Brooklyn neighborhoods of Williamsburg and Greenpoint, the Bloomberg Administration attempted to strike a balance between public benefits and private investment. The city’s plans rezoned an underutilized industrial waterfront to create significant new housing with 20 percent affordable residences and waterfront green spaces—including, a large public park located around a natural feature, Bushwick inlet.

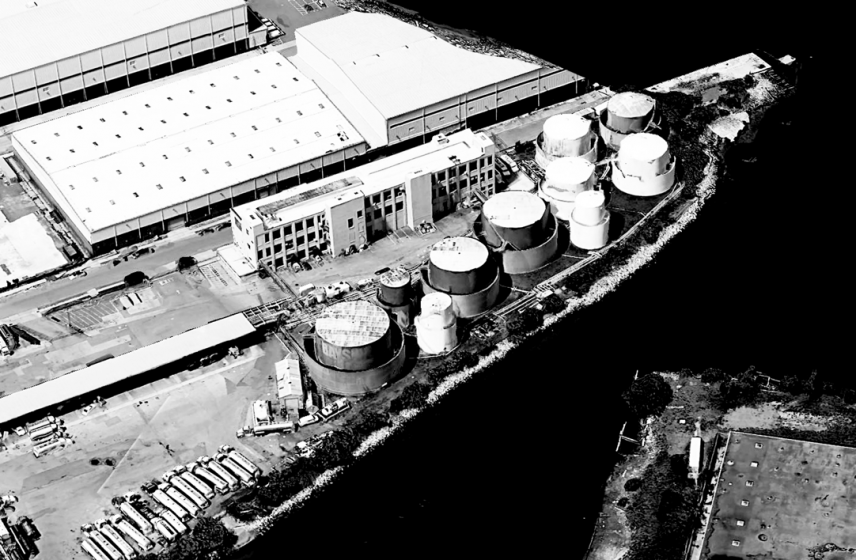

Bushwick Inlet also featured the abandoned Bayside Oil works: a former industrial site containing ten cylindrical steel tanks used to store petroleum. The tanks comprised two concentric cylinders of three sizes and placed in a picturesque composition along this inaccessible waterfront on the East River overlooking Manhattan. Years before, the tanks had been emptied and cleaned; tall grass grew up between them to recreate a surprisingly lush landscape supporting wildlife on this rare natural inlet within the tidal estuary uniting Manhattan, Queens, and Brooklyn.

The city’s rezoning was approved and executed surprisingly rapidly. New residential towers rose precipitously within former industrial sites, waterfront parks and ferry stops reconnected inaccessible waterfronts, historic warehouses were renovated, and economic, cultural, and social forces transformed a former working class community one subway stop from Manhattan into an innovative residential community—while escalating forces of gentrification and eradicating much of its history.

And one part of the plan wasn’t realized: where was the park?

The city unfortunately failed to gain control of the land designated for the park before the end of the administration; as values soared, owners refused to sell. With the rapid escalation of adjacent developments, the historic Brooklyn industrial waterfront was being rapidly erased by more anonymous architecture, and by 2007, the National Trust for Historic Preservation declared the Brooklyn industrial waterfront as one of the top 11 most endangered spaces in the United States. Stacey and Karen had looked closely at Bushwick Inlet park site and proposed a radical idea: instead of tearing down the former industrial structures, could they be reused to create a new kind of public park for this remarkable and rapidly transforming community?

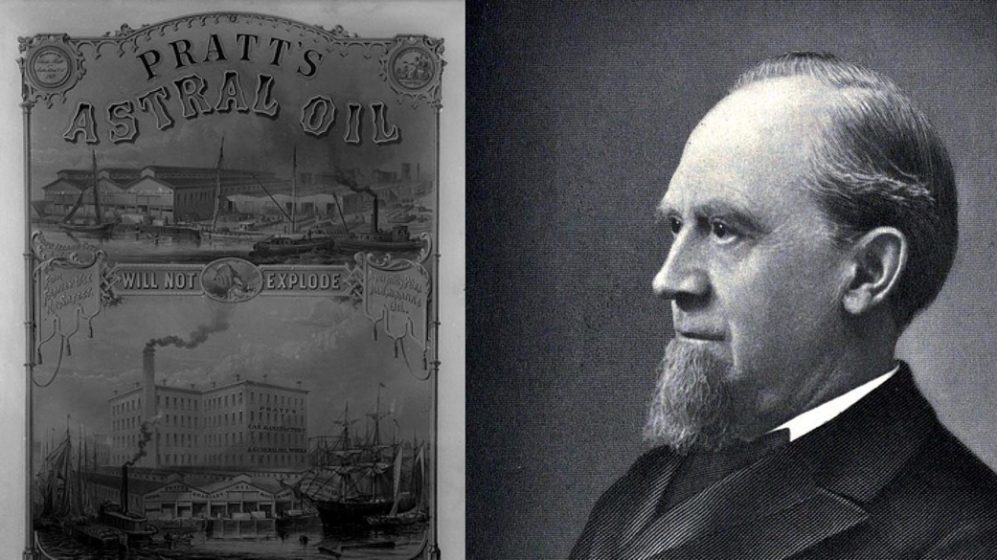

I was struck by Stacey’s and Karen’s vison. Their idea was grounded in this special site where nature, industry, and oil combined in a unique urban history: a natural inlet with significant wetland habitat. It was transformed by early industry: the site of the shipyard in 1861 for historic iron-clad, semi-submerged ship theMonitorand the site of an early American industrial story: Astral Oil Works. Founded by one of America’s extraordinary philanthropic entrepreneurs, Charles Pratt, who sold the site to arch-rival John Rockefeller and used the money to found philanthropic endeavors including social worker housing and the Pratt Institute, his progressive institution offering low-cost educations to diverse students including women and people of color. Stacey and Karen, along with the third original founder, Zac Waldman, and inspired by these stories named their proposal “Maker Park” to respond to the neighborhood’s history and current potential.

I suggested if these young activists wanted to explore making their vision into a reality, they would need concrete design proposals to galvanize support and demonstrate to the community what their park could be. My architecture firm STUDIO V Architecture worked with officials, communities, and consultants on actual waterfront projects, and I offered our services pro bono, suggesting we’d need a team to explore their vision and address the complex needs of a public waterfront park.We would need many kinds of expertise, so we reached out to world class landscape architects, scientists, environmental lawyers, remediation specialists, and structural engineers. Not a single person or firm whom we asked turned us down; everyone worked for free. Ken Smith the internationally known landscape architect signed on as our key design collaborator. And the team that created Maker Park was born.

We slipped through a narrow gap in the hoarding. An abrupt jump-cut shifting from teeming urban street to the quiet hush of overgrown urban woods surrounding a hidden inlet. Sights and sounds shift, the din of the streets fading to gentle waves lapping rocky shores, points of light fragment leaves and water surround a waterfowl rising into the sky against the modeled shadows of ten massive cylinders framing the skyline of Manhattan.

We began with a series of principles. A decade before when the city proposed the park, they conducted community outreach, and our team immediately decided to incorporate every element the public requested: athletic fields, a great lawn, boat launches. The team also studied what was not included in the city’s 2005 studies. The proposed park made no provision for habitat restoration, no reference to the site’s history, and no facilities for the community’s innovative culture of arts and performance.

Finally, there was no mention of resiliency but the inlet was a gateway to flooding the surrounding neighborhood during Superstorm Sandy. Our team saw opportunities to combine new ideas with older ones to improve the design for the community.

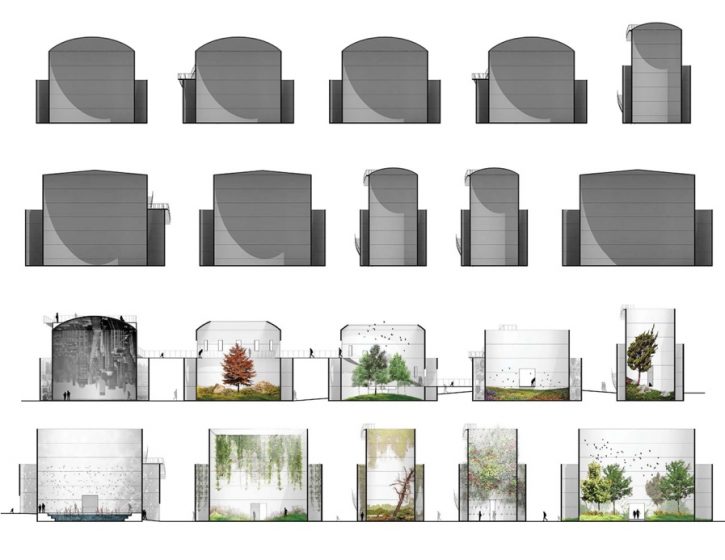

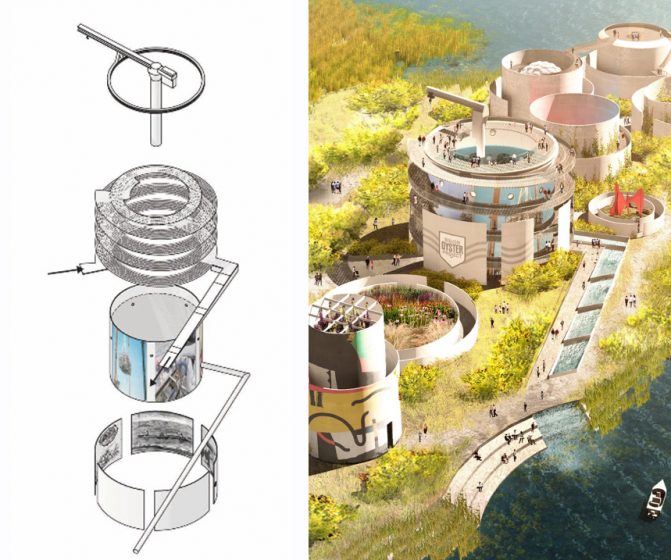

The team worked together on a collective design that incorporated these ideas, and more. The tanks, just five percent of the park area, represented a unique opportunity to create something completely new: a series of circular gardens that would preserve and reinvent the site’s history in a new way. By removing the roof of each central tank and adding passages and openings, the former tanks would feature a unique series of circular gardens connected by paths. Each tank would offer a different garden or amenity: a grove of trees for picnicking, a pool of water encircled by vines, a children’s adventure playground wrapped with murals by local artists, and a performance amphitheater topped with an observation platform overlooking the skyline.

There were challenges. We knew the site was polluted, so our voluntary team of scientists and attorneys utilized the Freedom of Information Law to obtain 10,000 pages of documents from multiple agencies describing the site’s conditions. The team created a RAWP (Remedial Action Work Plan) that explored options and costs for remediation. We did detailed cost analyses, determining that if the site was dug out, it would cost $220 Million, but if we filled the tanks with soil, used their concrete foundations to cap the site, the gardens would bio-remediate-in-place the limited petroleum for only $23 Million, or one tenth the cost—with the savings going to build the park faster and more safely for the community.

One early idea was the park would not be static, but offer changeable uses. Some tanks could offer changeable venues and installations while others were fixed. We included a large open lawn with a circular boat launch and curved planted berm encouraging performances while shielding the neighborhood from storm surges. And we re-designed the inlet with salt water low and high marshes, introducing gradients to restore native species and promote habitat restoration. The team began to display and publish initial designs and concepts, to gain input and support.

When we proposed our ideas, we didn’t know what to expect. Over time, hundreds of people came out in support of the vision, and the design gained recognition from state, national, and local design and non-profit organizations: the American Institute of Architects, Architizer, World Architecture Festival, and many more.

But nothing in New York is without controversy. A few key community members opposed the design, saying that the site needed to be wiped clean, and wanted all memories of the former industrial artifacts erased as a bad memory of their fight to create a park. They stated that nothing could remain, and only open space mattered.

Compromises were struck. A non-profit, the Waterfront Alliance, offered to mediate between the opposing visions– but the community leaders declined to talk. There was a debate over open space. The original design proposed renovating an existing small building as a community “maker space” for local residents with an accessible green roof– but not everyone supported this and felt it reduced the open space. The founders debated and decided to eliminate the building to address the community’s concerns and focus on the tank gardens. Differences in opinion led to Zac leaving the group. Stacey and Karen redoubled their efforts to engage with the community, and the design team rallied to support them. As the design focused on the circular gardens they renamed their non-profit vision The Tanks.

In the final stages of the design, a final and remarkable new idea was proposed. Another non-profit group, the Billion Oyster Project is dedicated to restoring New York’s harbor through rebuilding its original oyster habitat. This group spent years exploring this idea creating oyster research stations through NYC’s waterways, and using tanks at the NY Harbor school to grow young oyster embryos on donated oyster shells from restaurants to seed the harbor to restore the necessary reefs to reestablish the harbor. Their current entire oyster-growing tank capacity reached 10,000 gallons. We proposed redesigning one tank as an oyster habitat laboratory and educational center, holding nearly a million gallons and allowing oysters to be restored directly to Bushwick Inlet, which their research had shown was one of the most favorable locations for oyster habitat on the entire waterfront. The design featured a spiraling ramp inspired by the Guggenheim Museum allowing school children to ascend the tank, engage the oyster restoration efforts, while learning the story of the destruction and restoration of the New York Harbor.

A social media petition went on line at savethetanks.org. It started gathering hundreds of signatures per day. But perhaps it was now too late. The machinery of government had set into motion at last. Lacking funds to build the park, facing criticism from the community leaders who insisted on wiping the site clean, the government needed to show it was doing something after so many years. So, it did the only thing it could to show change at the site. It finally tore the tanks down.

Now the site of the tanks is an empty rubble and dirt covered lot, wrapped by fences, all the verdant greenery stripped bare.

CODA to an INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

Even as these industrial artifacts came down, it was ironic to see the support, including signatures and awards for the project only continue to grow. They continue to do so today.

Perhaps there are some lessons in this story. First, there is never enough community outreach, and people must speak to one another, early and often in any public process to reach consensus and show the potential. Social media can provide a tool for gathering the real support for people don’t always attend public meetings. We shouldn’t be afraid of innovative ideas to create new kinds of public spaces. And in an age of ever-increasing obsolescence of buildings and structures: we shouldn’t be afraid to recognize and address our own history and reuse structures in creative ways.

At the same time, the principals we established for our design continue to inform and transform our work today: reusing artifacts from our industrial past and giving them new life, and creating public spaces that are transformable, to respond to the ever-increasing forces of technological obsolescence. Finally, but perhaps most importantly, this example has reinforced for us more than ever that our waterfront designs must promote habitat and help our beleaguered waterfront cities address the urgent need for resiliency in a time of profound climate change.

Perhaps a few others saw the lessons as well. While showing our work for the Tanks and Maker Park, I was asked to go back to revisit those structures I explored as a young student. Today STUDIO V is redesigning the abandoned grain elevators in Buffalo, into an arts and cultural center, including a sustainable residential and commercial community within the old industrial structures.

And the two women that founded the original concept? One was traveling overseas recently, and was asked in Tel Aviv if she had heard of a project called The Tanks. Surprised, she answered yes—she not only knew about it, but was one of the founders, although it had sadly now ended with their destruction. They happily informed her that their city was inspired by our designs, and had designated one of their own former industrial tank farms as a public park—and was using our design as a model to explore creating a new kind of park with circular gardens in their tanks.

As designers and urbanists we all want to realize our visions for cities. And we’re disappointed when they fail to be realized. But sometimes, an idea may in itself be a beginning. And if strong enough, if it resonates with enough people, if it tells our stories, addresses our collective myths and challenges, maybe an idea is enough to carry on, and assist other communities and cultures, to help their people address their needs for new kinds of public spaces, cultural amenities, historic preservation, resiliency, and creative new designs for green open spaces.

This is how I believe we will work together to successfully reinvent our cities.

Jay Valgora

New York

THE PRO BONO CONSULTANT TEAM:

THE FOUNDERS: KAREN ZABARSKY and STACEY ANDERSON

STUDIO V Architecture, Architecture: Jay Valgora, Tom Arleo

KEN SMITH WORKSHOP, Landscape Architecture: Ken Smith

COZEN O’CONNOR, Lobbyist and Counsel: Katie Schwab

SIVE, PAGET & RIESEL PC, Environmental Attorney: Michael Bogin

TENEN ENVIRONMENTAL, Environmental Engineer and Remediation: Matthew Carrol

CAPITAL ENVIRONMENTAL CONSULTANTS, Environmental Scientist: Greg Fleischer

PENTAGRAM, Graphic Identity: Luke Haymen

TILLOTSON LIGHTING ASSOCIATES, Lighting Design: Suzan Tillotson

6 SQFT, Editorial Partner: Dana Schwartz

While the vision for Maker Park is interesting/inspiring in theory, this entire narrative completely disregards the failure of the team to engage in any meaningful way with the very large and diverse community who fought for the park to be a reality – and were actively engaged in a real fight to actually secure the land ten years after the rezoning. Dozens of protests, actions, and campaigns with the City while at the same time the Maker Park team was securing resources for their own fantasy project. If Jay and his pro-bono team had sought to actually work with stakeholders as opposed to just ram forward with their own vision, it would have actually been beneficial for all. In the end, people resented the project simply because of the arrogance and aggressiveness of the Maker Park team.

Well done! Impressed with your creative and inclusive visions. MayYour efforts and truths live on.

The Nature of Cities is a critical link to bring the innovative and the genius of incubated ideas, turned to reality, for climate change solutions from cities around the world.