“the knowing self is partial in all its guises, never finished, and can thus only develop in combination with others.”

— Donna Haraway in Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective, p586

I grew up in Singapore. I heard stories from my father about when he was a child and how it used to be in the kampungs—Malay for traditional villages. He would go out with a net to hunt for frogs early mornings before dawn and scurry down drains to catch tadpoles and small fishes. Amidst many other kampung stories, that version of Singapore feels like a whole other world—the experience of living on the land here, has shifted drastically within a short span of a generation. Today, Singapore can be seen as a notable example of rapid urbanisation whilst attempting to ensure urban greening proliferates in the city.

How can we come to be aware, know, and acknowledge both empowerments and limitations of the different ways we come to sense make and understand the world around us? Is it possible to step out from the place of human agency to sense make? Looking for ways to cultivate awareness of co-influencement of all living organisms, creating art provides a space to question my human-centred perspective of the world and a starting point was to explore my understanding of what is “Natural” and “Unnatural”.

* * *

Attempts to engage the inside-outside division

During a field trip to Forsinard, in the Highland area of Scotland, I stood between the fences which formed the boundary between a section of untouched peatland and a section of pine trees that were introduced onto the landscape by man. The breeze was picking up. I closed my eyes. It was distinct—I could hear the manifestation of fences in the landscape.

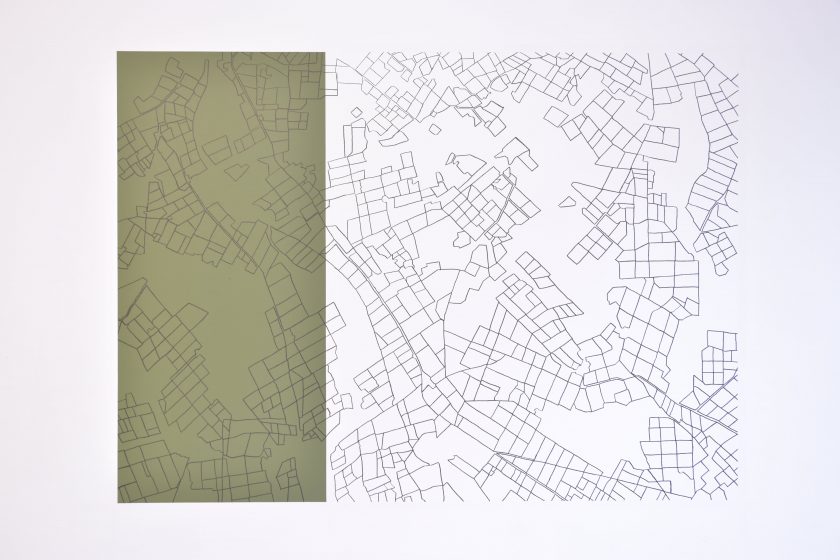

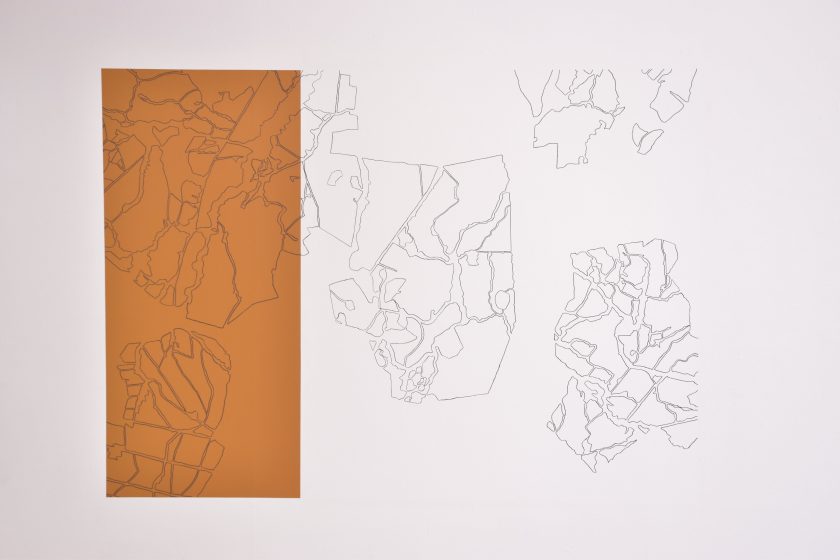

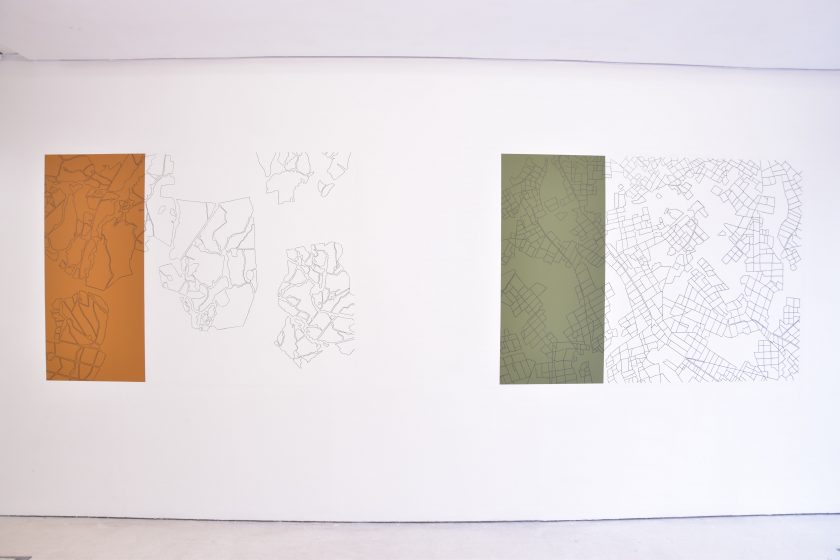

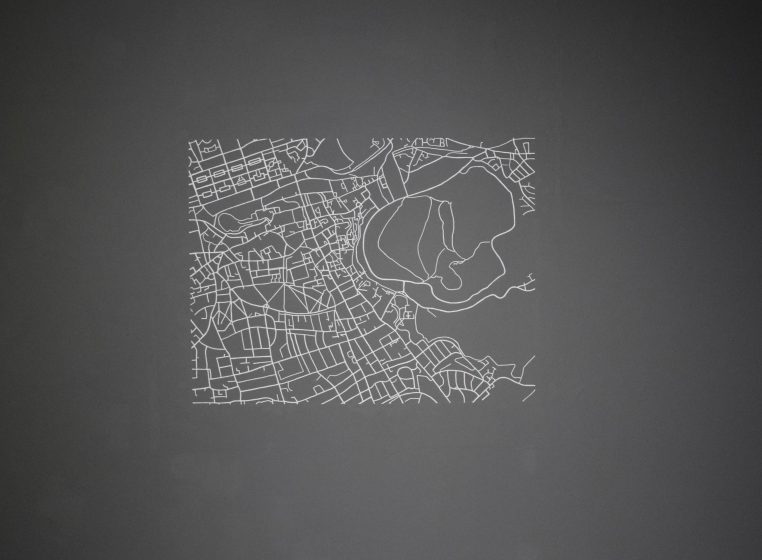

I interpreted the fences in the landscape as an analogy to the inside-outside division of how we categorize and order the world around us. Through Detached, the process of physical line drawings of the map-perceived boundaries within the landscapes of Caithness and Sutherland, I was further imposing on the separation that comes from categorising “nature” as a matter which exists outside of my body.

The use of the gallery wall as canvas was an attempt to undo the single momentary impression of the impermanent and ever-changing landscape that I had taken. I wanted to find comfort in the process of returning the wall space to its original condition as a metaphor for (re-)entering into another state of mind. Perhaps one day, we are able to embrace a state of being that does not drive the inside-outside division. Perhaps the division can be dissolved from finding the balance between trust of our sensorium and reliance on our cognitive abilities.

Do other living organisms struggle in finding this balance, or engage with the inside-outside division? How can we begin to understand the reality of other organisms? Would it help to experience reality from another perspective?

* * *

Stepping out and in and out and…

…exploring reality with new perspectives through interactions with those coming from different disciplines, specifically the sciences.

Crossing disciplines proves to be stimulating and engaging, leading to more questions than answers. We rely on our cognitive abilities. Are the majority of us trapped within a frame of mind shaped by perspectives that are enabled only via western science? Has this led to the separation of us from the ecology of living organisms?

In Western tradition, the tendency to recognize human beings at the top of the hierarchy of beings is perhaps the seed of the capitalistic approach we take towards living. What would happen if we were able to experience the animacy—i.e. aliveness—of the world and give equivalence to all living organisms?

“The language is the heart of the culture; it holds our thoughts, our way of seeing the world”.

— Great grandmother quoted by Robin Kimmerer in Braiding Sweetgrass Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants, p50

One of the indigenous languages of the Americas, Potawatomi, an Anishinaabe language, is a predominantly verb-based language and holds most naturally occurring objects as animate beings—rocks, bays, apples, trees and the list goes on. Items that are man-made are inanimate, for example, a chair. In every sentence, it allows us to incorporate respect to the animacy of the world and reminds us of our kinship with the animate world around us. Imagine, relating to the world in this light instead of separating anything non-human, as an “it”.

I grew up with shadows of eastern beliefs and practices such as the teachings of Confucius, and herbal remedies for illnesses from the practice of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Coming from a family with ancestry line from China, paired with rapid westernization in our social culture producesa difficult reconciliation, which creates tension.

Drawing upon this tension as an analogy for the narrow perspective we hold of understanding ecology and other living organisms around us gave rise to another piece of work, a botanical glimpse.

“There was a time where I teetered precariously with an awkward foot in each of the two worlds—the scientific and the indigenous. But then I learned to fly. Or at least I try. It was the bees that showed me how to move between different flowers—to drink the nectar and gather pollen from both. It is this dance of cross-pollination that can produce a new species of knowledge, a new way of being in the world.”

—Robin Wall Kimmerer in Braiding Sweetgrass Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants, p47

“Taxonomy, i.e. the classification of the natural world whilst a useful tool, is a system of order imposed by man and not an objective reflection of nature. Its categories are actively applied and contain the assumptions, values and associations of human society” —Mark Dion in Theatre of the natural world

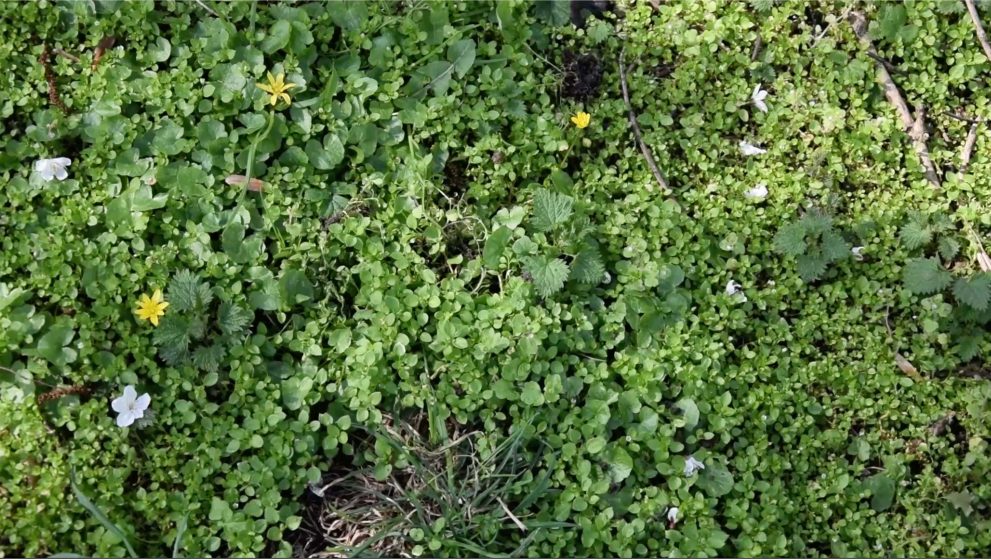

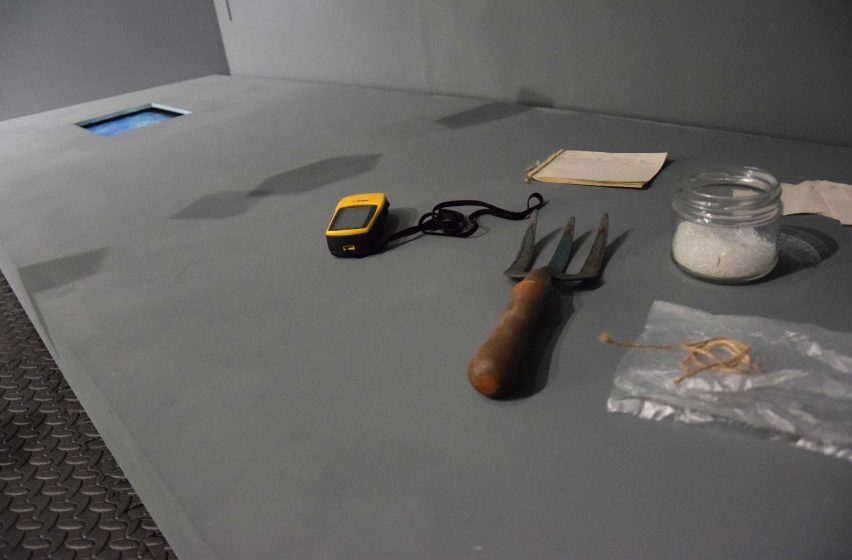

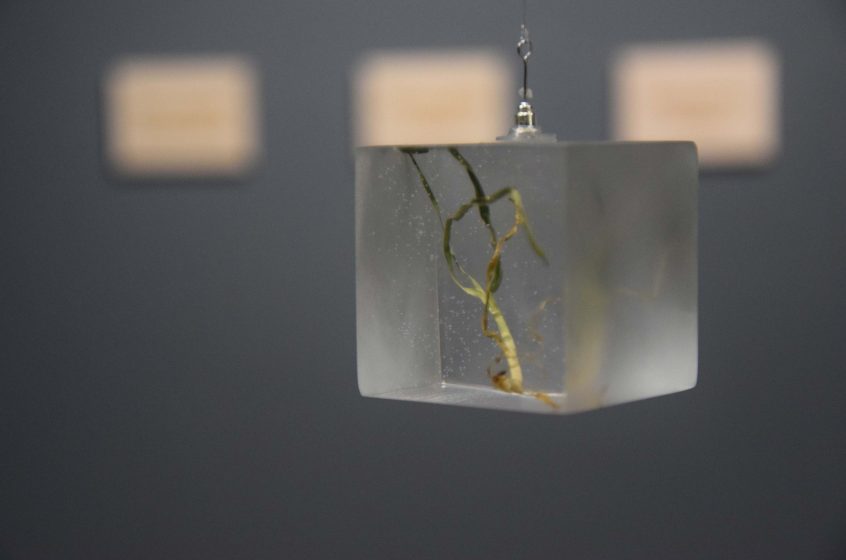

a botanical glimpse attempted to reconcile and put to question the outcome of such an approach—i.e. western scientific methods—and the role of cultural institutions in our perception and relationship to the world around us. Through the use of a theatrical setting of a botanical collection which viewers enter into, it lends itself to the embodiment of authenticity as a way to validate the models of knowledge we have come to rely upon—familiar yet circumscribed.

The sampled area for the botanical collection was determined via a process of walking through a nearby urban ecological landscape with botanist, Dr. Heather McHaffie from Royal Botanical Garden Edinburgh. The choice of area intended to draw attention to our entwined co-existence with often overlooked living organisms. That the biodiversity found exists within such a small sampled area—0.07m2—further highlights the ease with which such organisms are overlooked.

Through the process of creating a botanical glimpse, I participated in the beginning phase of a knowledge creation process—in a systemically and scientifically acknowledgeable way—by ensuring the methodology I engaged in is sound.

Aware that I have no formal training in such scientific methods reflects the process of reiterating our ways of creating knowledge; it is based on a human-centric belief system. In this way, I placed myself in the role as a creator of knowledge as an attempt to understand the way we come to know and perceive knowledge.

The isolation of each species found within the field sample area brings attention to and serves as an analogy of how within knowledge creation today, where we place significant emphasis in looking at things in parts—broken down to the molecular level—in the attempt to understand and sense-make of the world around us. Furthermore, the use of resin casts to present a part of the collected plants in an immortalized, encapsulated form echoes the routine of separating ourselves when observing what is around us.

* * *

Have I come closer to stepping out from the place of human agency and encountering the co-influence of all living organisms? In the end, creating art neither answers nor knows, instead poses more questions about what it might mean to be a living organism. Perhaps the only certainty we can hold for ourselves is the gap between how the world appears to us, and the world as such. We owe it to ourselves to keep trying, to experience and close this gap by repeatedly re-knowing ourselves, each time, closer to nature.

Audrey Yeo

Edinburgh

Add a Comment

Join our conversation