Beyond the direct effects of the pandemic on mobility, and the effects of indoor time on health, Covid-19 sheds a strong light on challenges to urban resilience. Our research was—pre-pandemic—focused on the role of urban greenspaces for ecosystem services and environmental justice. The variation in restrictions and reactions to the pandemic across our cities shows a gradient from Barcelona and New York to Stockholm. This reinforces the importance of comparative research on resilient urban development, while triggering new questions.

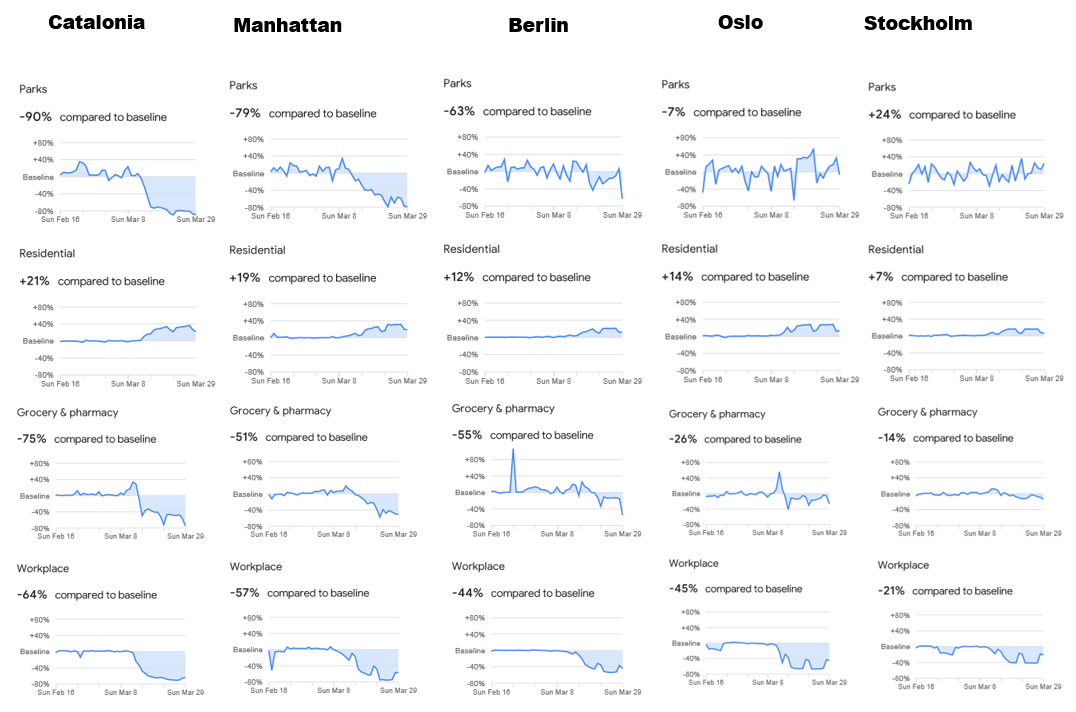

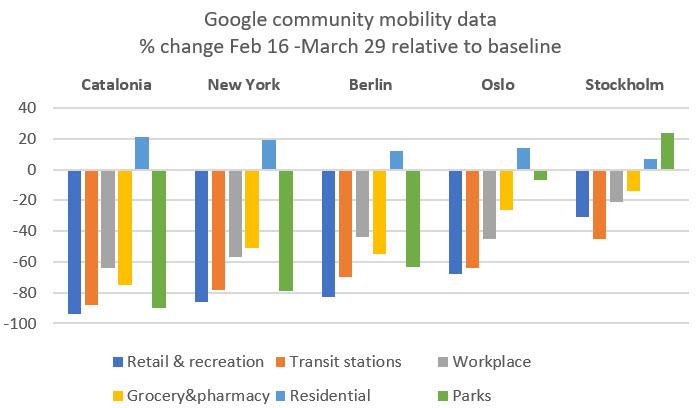

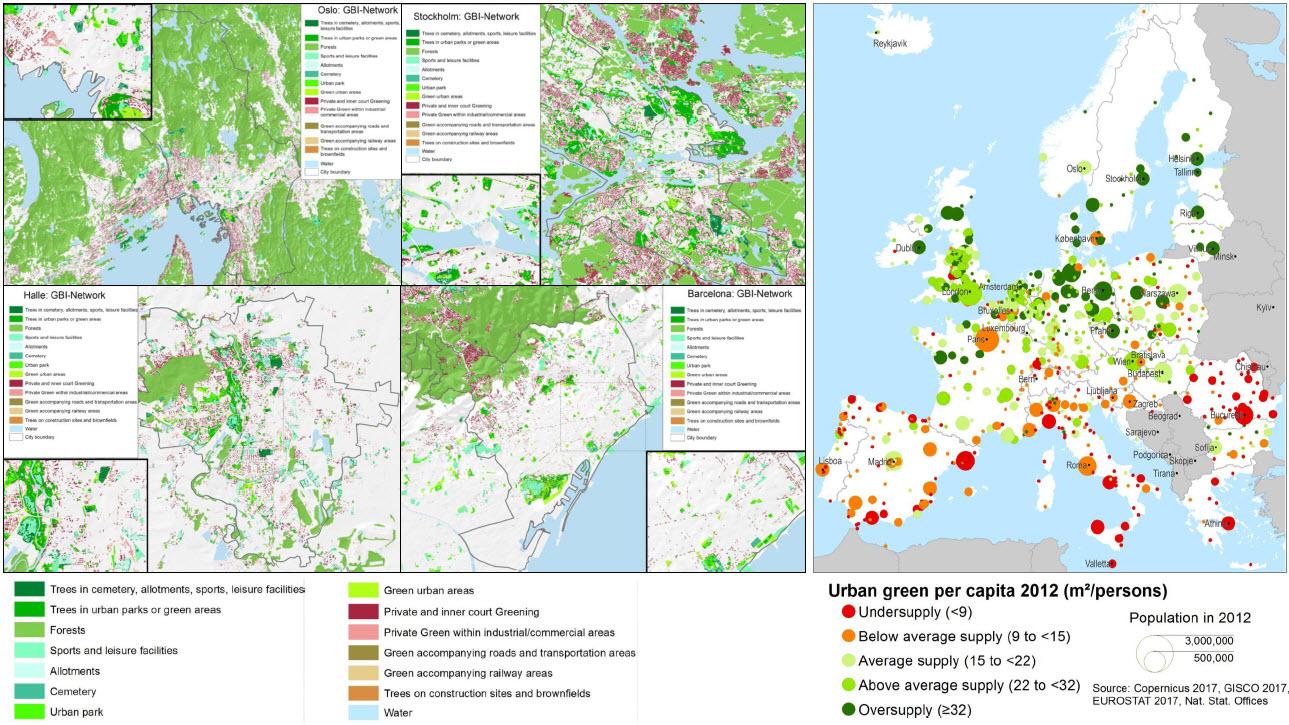

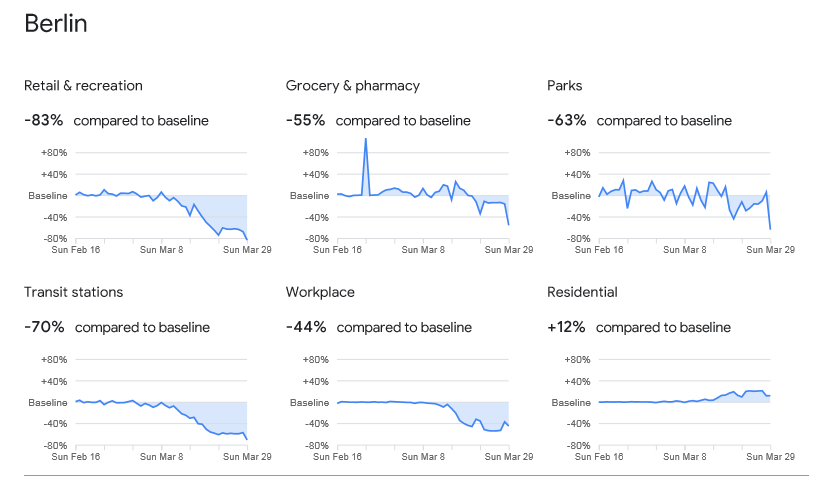

The severity of the lockdowns on workplace mobility has been stronger in Barcelona and New York than Berlin/Halle and Oslo, which in turn have had stronger restrictions than Stockholm. The severity of the pandemic and restrictions seems roughly to coincide in the case of our cities with urban density and greenspace availability per inhabitant (see below).

The reactions to Covid-19 and impacts on access to greenspace raise a number of questions which cast previous research results “in a pandemic light”. Is the loss of access to greenspace larger in areas hit the hardest by the pandemic? Are other environmental problems correlated with the incidence of Covid-19 and its restrictions? Is the distribution of greenspace and the loss of access equitable across neighbourhoods? Are new open spaces such as brownfields being used, and does the lockdown increase the importance of green roofs in dense cities? What is the effect on children and public health of indoor confinement? What of a pandemic lockdown in a future climate change scenario with heat waves?The Google mobility data for residential area and parks triggers questions about the importance of greenspace during the pandemic. Can the resolution of the mobility data be improved and compiled specifically for the urban areas hardest hit by the pandemic? In the following we look at some of these gaps and questions city by city.

Berlin, Leipzig, Halle, Germany by Dagmar Haase and Andre Mascarenhas

The Google mobility data describe only partly what you can observe on the streets of large German cities like Berlin, Leipzig, or Halle. People limit shopping (retail, grocery, pharmacy), but our general impression is that more people seek being outdoors, meaning walking in their residential area as shown in the Google mobility data, but also in green spaces. You see many more people jogging compared to pre-corona times. People are innovative in lawn-based activities, since playgrounds and sports fields are closed, which highlights the importance of lawns as recreational places. Interestingly, there is evidence for the importance of open spaces other than parks, such as brownfields. Previously, they were basically for walking the dog, but are now also used for family activities and jogging more than before. One reason might be that brownfields are less observed and visited by the police and thus people feel more free. Another relevant type of non-park green space is urban forests, where similarly it can be more difficult for the police to control people’s behaviours.There is evidence that important urban forests like Grunewald in Berlin are intensively used. Reasons to use such spaces have to do with people finding them relaxing and calming, wanting to enjoy their beauty or experience wilderness, or believing that they have a positive influence on their well-being. For the coming weeks, namely until 3 May when restrictions will be re-discussed in German government, if numbers of infected further decrease and the r-value remains below 1, more and larger shops will reopen, walks for shopping will most probably increase, while those in residential neighbourhoods and parks might decline (being replaced by shopping walks/ways). In terms of existing inequalities in the uptake of ecosystem services from green spaces in German large cities, it is still hard to judge without monitoring data, but existing evidence indicates that there is unequal socio-spatial distribution of urban green space, translated in differences in the quantity and size of green spaces, the structure of vegetation, and their quality. These inequalities and their negative effects on the worse off can become very important in situations like the corona lockdown.

We think those inequalities remain more or less the same when it is about parks, they only become much more visible due to the mobility restrictions in place. Of course people with residential / private green definitely can draw more benefits (like enjoying fresh air or gardening)than those without. Those with a view into urban green also draw some benefits, particularly if they have a balcony, allowing them to “go outside” or do some gardening. These factors are related to existing inequalities in the housing market but, of course, now they become simply more evident. The Corona situation has highlighted the need to put more emphasis in developing high quality green spaces in all districts and areas of the cities, as in times of such mobility restrictions both short distances (as public transport is not advised) and good quality of urban greenspace would be urgently needed.

Finally, in terms of this pandemic, the virus occurrence and the reaction to it brought two things onto the desk of Leipzig and Halle’s urban greenspace development: First, as mentioned above, a more equal (fair) distribution of high quality green spaces for recreation across the entire town. Second, to develop more “wild” areas where people have NO access and wildlife can develop and form independent biocenosis and thus prevent zoonoses as best as possible. This point is particularly important for the joint planning of cities and their wider peripheries.

Barcelona by Johannes Langemeyer and Francesc Baró

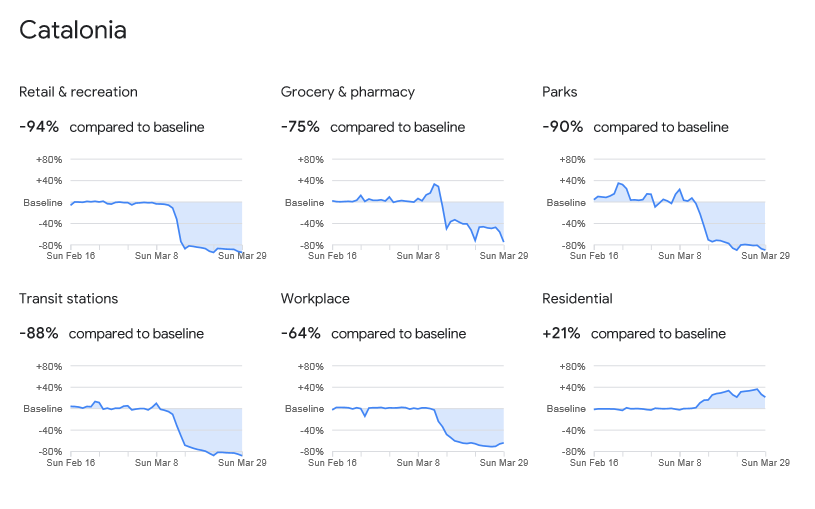

As Covid-19 infection rates started to increase, Spain declared a countrywide state of emergency and put in place and restricted people’s mobility and especially activities in public space drastically (see decree here). As a consequence, in Barcelona as in other Spanish cities—but in sharp contrast to all other cities considered here—the accessibility of public green spaces has been limited to dog walking (though restricted as well, this benefits a substantial share of the population, as the ratio between dogs and people in Spain is about 1:4). Other highly appreciated recreational activities like outdoor running or cycling are penalized by high fines, while most urban parks have been closed since mid-March. As a consequence, park use drastically dropped by about 90%, as shown by the Google mobility data.

First of all and most generally, it is relevant to question whether there is a general underappreciation of particular nature values among decision-makers and the broader Spanish society compared to other European countries. This could constitute an important general barrier for the implementation of nature-based solutions and other greening strategies in cities (lacking trust people’s responsible behaviour could be another explanation). Interestingly in this context, in Catalonia, the strict initial regulations have been rapidly softened for accessing vegetable gardens (positively affecting about 10,000 gardeners in the metropolitan area of Barcelona) once more showing the importance of gardens in moments of crises, while softening access to urban parks, e.g. for individual exercising as in other European countries, has hardly been in the discussion.

Secondly, and maybe most discussed right now, at least in Barcelona, are potential negative physical and psychological health effects primarily on children due to lacking outdoor recreation, also long term. Despite relatively low scientific evidence for the effectiveness of children’s isolation, the Covid-19 restrictions in Spain are even more severe for children than for adults—apart from a few exceptions children were not supposed to leave the house at all during six weeks (after strong public pressure relaxations in the regulation have been implemented from 26 April onward). Yet, potential negative health effects such as obesity and anxiety, which could be mitigated by access to urban nature, are not limited to children but affect adults similarly.

Thirdly, and related to the previous points, the lockdown can be assumed to affect already vulnerable social groups unequally higher, and reproduce existing environmental injustices. Given that low income residents generally live in smaller apartments and are assumed to have less access to private green spaces, the privation of access to benefits from public green spaces is likely affecting low-income groups disproportionately stronger than more affluent citizens. At the Barcelona Lab for Urban Environmental Justice and Sustainability (BCNUEJ) we are currently investigating this unequal accessibility to greenery under lockdown conditions in relation to unequal health impacts through a Spain-wide online survey.

Fourthly, the lockdown puts Barcelona’s about 2700 ha rooftops in the spotlight of future urban resilience strategies, which have become an important gathering and recreational space for neighbours during the lockdown. In an extremely dense city like Barcelona (at least for European standards) unused rooftops bear an important transformative potential. This has more classically been discussed in the context of solar energy production, while more recently mitigating peoples’ needs for ecosystem services through green roofs is gaining relevance in the debate. This debate must be reshaped considering multiple and potentially interacting drivers of change.

Finally, the severe lockdown might indicate potential solutions for one of Barcelona’s most pressing environmental issues before Covid-19: Air pollution. Which might even have increased the lethal effects of Covid-19. Regarding the Barcelona Public Health Agency, air pollution is causing over 350 premature deaths each year in Barcelona (in comparison, the number of deaths by Covid-19 between 1 March and 10 April has been estimated at 2,236). For Barcelona, we observed that air pollution has dropped by more than half, compared to the same period in 2019, showing a much wider effect than the recently implemented low emission zone. In this context we are starting to question, to which extent we are capable of avoiding a return to the pre-Corona “normality”, at least with regard to emission intensive transport.

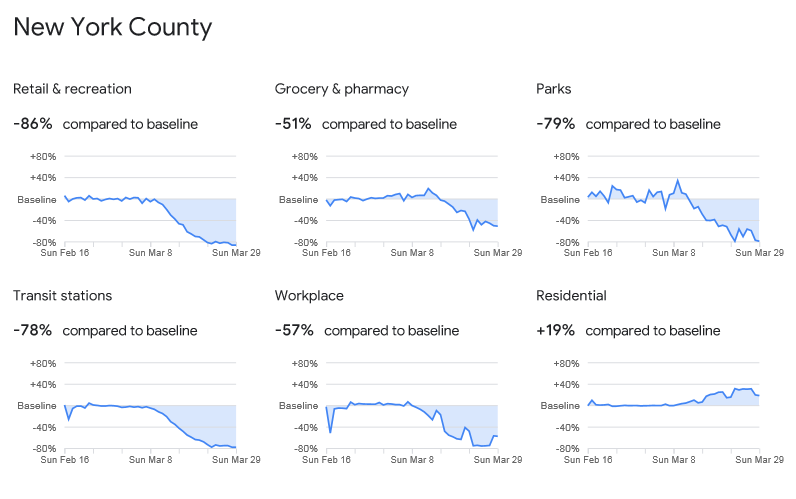

New York by Chris Kennedy, Zbigniew Grabowski and Timon McPhearson

New York City is unique among ENABLE cities in that under the weak federal system of the United States, significant responsibility for Covid-19 response falls to states and municipal governments. NYC current caseload (180k confirmed cases as of this writing), has labeled it as both the current “epicenter” and the “vanguard” of the pandemic in the US.

In order to rapidly learn how NYC’s experience may inform response efforts elsewhere, the Urban Systems Lab at The New School has been examining patterns of Covid-19 spread and relationships to multi-dimensional vulnerability. For instance, we have noted that the mobility restrictions put in place by NY State Governor Andrew Cuomo’s Executive Order “NY on PAUSE” (Policies, Assure, Uniform, Safety, Everyone), reflected in the Google mobility data, appear confirmed by transit, electricity use, and geo-coded tweets across the city. The USL has also begun to aggregate additional mobility data from Twitter to examine covid responses.Given the magnitude of the difference in increased residential mobility and decreases across all other sectors, these data suggest that most public realm activity in the city is driven by non-residents now restricted to their home jurisdictions, which may be true across ENABLE cities. However, data on testing totals and confirmed cases also indicate that social vulnerability to Covid infection and mortality may be driven by socio-economic and racial disparities, existing issues of environmental justice (e.g. air pollution), and workforce hierarchies. For example, the historically low transit ridership declines (87% down according to the MTA), are not uniform across the 5 New York City boroughs, highlighting equity, access, and socio-economic issues. In low-income neighborhoods ridership is more consistent with data from this time last year, with reports of overcrowding as service is disrupted.There is also strong reason to suspect that the mobility data also do not accurately reflect the uses of parks by local residents, who have observed local parks becoming much more crowded than usual. NYC being a dense megacity (population density averaging ~2800 residents per sq km), with a relatively low greenview index, private and community green spaces providing numerous ecosystem services, were already highly sought after, and the city’s extensive green roof programs may become increasingly important. Additionally, ongoing efforts to make more of the streetscape useful for pedestrian, bicycle transit, while managing stormwater and heat hazards at a finer scale, may also gain in importance, although existing USL research (in preparation) shows that planning remains fragmented in these domains. For example, the city’s nascent attempt at a city wide bicycle network could be expanded to integrate nature-based solutions and green infrastructure. Aside from NYC being an international and regional destination, much work remains to be done on how extending NY on PAUSE will affect the vulnerability of residents to the oncoming extreme heat and flooding season.

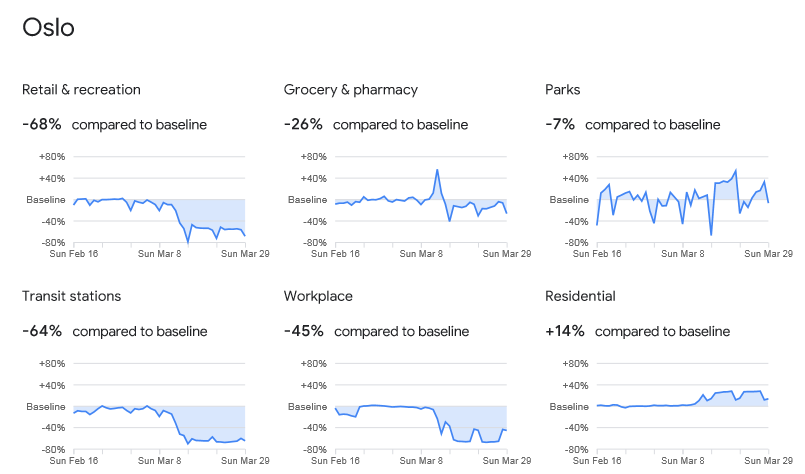

Oslo by David N. Barton, Norun Hjertager Krog , Zander Venter , Vegard Gundersen

Oslo’s Covid-19 mobility to non-essential workplaces decreased by 45% in March and increased residential mobility by 14%. Outdoor recreation was advised within one’s municipality in Norway, following social distancing advisories. We wonder whether physical exercise has been more spatially distributed during the period of mobility restrictions. Oslo is surrounded by continuous boreal forest cover with public right of access. Data from automatic counters indicate that people use new entrance areas and are dispersed over large forest areas on marked and unmarked paths. Oslo has plenty of room for recreation in the city’s peri-urban forests. However, with the advisory against public transport, those who live in the city center without a car must use urban parks and open spaces for recreation. While there is a small reduction in use of parks (-7%) since February as a whole, there was a large increase in park use following the shock of the March 12th announcement. Oslo’s citizens may have compensated for mobility restrictions by increasing outdoor recreation in parks, streets and forests close to home. The density of vegetation in streets may also be an incentive to exercise close to home.

Unfortunately, the Google community mobility data does not identify mobility in streets and undesignated greenspaces such as Oslo’s peri-urban continuous forest cover, the Marka forest. Neighbourhood green spaces accessibility, size and quality, as well as tree density in general have shown to have positive impacts on mental and physical health. Street level greenviews in Oslo are high compared to other capital cities, and green spaces are relatively equally distributed across the city, although some differences in exposure to green and other environmental quality still exist.

The importance of residential tree canopy may literally grow if a pandemic lockdown occurs during a heatwave. In Oslo each tree canopy reduced average excess heat exposure to the elderly by one day during the heatwaves of 2018. We speculate that urban tree canopy’s importance for public health and urban resilience can only increase, with Oslo’s summer temperatures in 2050 expected to be over 5 degrees warmer. Ease of access to cool, large, low recreation density areas in the Marka peri-urban forest and Oslofjord should increase the value of urban ecosystem services in futures with climate change and pandemics. These peri-urban areas may also serve a spectrum of different opportunities for activities and nature experiences for the urban populations, as they include an environmental gradient from intensively managed service areas towards untouched wilderness areas within short distances. This means that people do not need to travel far near Oslo to achieve experiences such as silence and solitude.

Despite authorities assurances of food security, the announcement of Covid-19 restrictions 12 March saw an approximate 50% spike in grocery & pharmacy visits in Oslo. Although this brief hoarding was probably focused on non-perishables, we wonder whether this behaviour will be lower in cities with better access to urban gardening and local agriculture.

The next Google mobility report will cover the period including Easter. Easter is traditionally a time for outdoor activities in Norway, mainly skiing activities in the mountains. Many people go to their cabins, but since this was prohibited, we expect the use of urban greenspace will show an increase in mobility—at least to the extent that people have adhered to the advice from the Government to walk from home, and avoid crowded car parking spaces and public transport. Local newspaper reports also indicated that the peri-urban Marka forest was extensively used during Easter, perhaps covering similar recreational needs of outdoor life as going to the cabin, while also offering more space for social distancing than the city streets and parks. Oslo’s peri-urban forests provide for resilient outdoor life during the pandemic, complemented by local access to parks and high quality urban spaces with street trees.

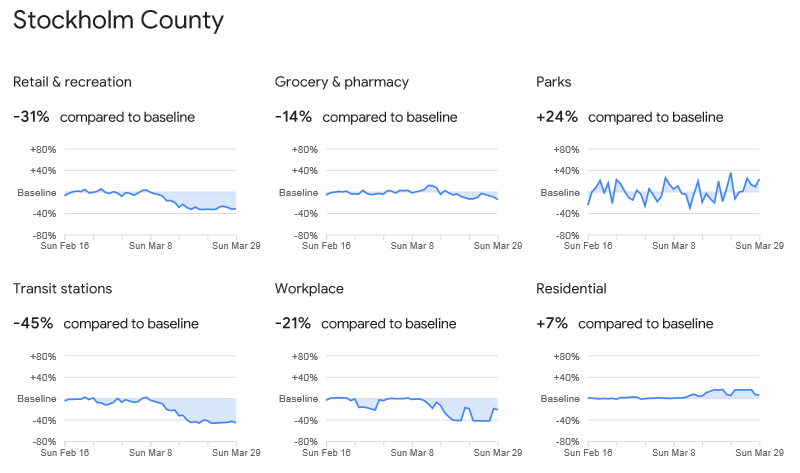

Stockholm by Erik Andersson

Stockholm residents have compensated for mobility restrictions, and restricted access to urban services like gyms, museums, concerts, sports events etc. by increased outdoor recreation in parks, streets and perhaps especially forests close to home. Similarly to Oslo, density of vegetation in streets may also be an incentive to exercise close to home. Stockholm has over the last few years rolled out a system of outdoor gyms to increase the multifunctionality of the city’s green spaces, and these have seen increasingly heavy use. Unfortunately, the Google community mobility data does not identify mobility in streets and undesignated greenspaces such as Tyresta national park, nature reserves and remnant green spaces embedded in Stockholm’s green wedges—only a smaller portion of these are designated as “parks”. Stockholm has ample access to water, and as we move into spring/summer this will open up additional opportunities for being out while keeping a distance from other people. Neighbourhood green spaces and tree density are shown to have positive impacts on mental and physical health. Street level greenviews in Stockholm are high compared to other capital cities, and green spaces are relatively equally distributed across the city, although some differences in ‘direct’ exposure to green and other environmental quality exist.Ease of access to cool, large, low recreation density areas in the green wedges, nature reserves and national parks, together with the archipelago and lake Mälaren should increase the value of urban ecosystem services in futures with climate change and pandemics. The importance of residential tree canopy will also grow in Stockholm if a pandemic lockdown occurs during a heatwave. Soft restrictions and social responsibility, together with a generally high availability of larger open spaces have made it easier for Stockholmers’ to shift activities and time to open space rather than the more built up parts of the city. However, restrictions for the use of public transportation means that the larger scale regional system of open spaces is primarily available for people with their own cars, skewing the distribution of opportunity across the population.

This is not the end

We hope the Google mobility data will soon show access to urban greenspaces increasing everywhere as restrictions are lifted, coinciding with the green views of spring. While we hope the pandemic and its suffering soon will pass, preserving, restoring and understanding the importance of greenspace for future urban resilience must continue with renewed force.

David Barton1, Dagmar Haase2, Andre Mascarenhas2, Johannes Langemeyer3, Francesc Baró3, Christopher Kennedy4, Zbigniew Grabowski4, Timon McPhearson4, Norum Hjertager Krog1, Zander Venter1, VegardGundersen1, Erik Andersson5

1—Oslo, 2—Berlin, 3—Barcelona, 4—New York, 5—Stockholm

about the writer

Dagmar Haase

Dagmar Haase is a professor in urban ecology and urban land use modelling. Her main interests are in the integration of land-use change modelling and the assessment of ecosystem services, disservices and socio-environmental justice issues in cities, including urban land teleconnections.

about the writer

André Mascarenhas

André Mascarenhas is a Post-Doc researcher at the Lab of Landscape Ecology, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, and the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, Germany. He is interested in human-nature interactions, especially regarding the links between biodiversity, ecosystem services and spatial planning in urban environments, under a sustainability science lens.

about the writer

Johannes Langemeyer

Johannes Langemeyer is a senior researcher at the Institute of Environmental Science and Technology at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain. He is trained as a geographer and environmental scientist. His interdisciplinary research focuses on urban social-ecological systems, at the interface of ecosystem services, resilience, and justice.

about the writer

Francesc Baro

Francesc Baro is a postdoctoral researcher at ICTA/Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, and member of the Barcelona Laboratory for Urban Environmental Justice. He is an environmental scientist trained in landscape and urban planning and explores the operationalization of ecosystem services in urban social-ecological systems.

about the writer

Christopher Kennedy

Christopher Kennedy is the associate director at the Urban Systems Lab (The New School) and lecturer in the Parsons School of Design. Kennedy’s research focuses on understanding the socio-ecological benefits of spontaneous urban plant communities in NYC, and the role of civic engagement in developing new approaches to environmental stewardship and nature-based resilience.

about the writer

Zbigniew Grabowski

Dr. Zbigniew J. Grabowski (Z or Zbig for short) is an Extension Educator in Water Quality at UConn’s Center for Land-use Education and Research (CLEAR). Z’s primary work is to support just transformations of land systems. His work focuses on green infrastructure, just transitions, and systems approaches to address intersecting social and environmental challenges.

about the writer

Timon McPhearson

Dr. Timon McPhearson works with designers, planners, and local government to foster sustainable, resilient and just cities. He is Associate Professor of Urban Ecology and Director of the Urban Systems Lab at The New School and Research Fellow at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies and Stockholm Resilience Centre.

about the writer

Norun Hjertager Krog

Norun Hjertager Krog, PhD, is a Senior Scientist at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health in Oslo, Norway. She is a sociologist and environmental epidemiologist, with research on associations between urban environment and health, including green space and built environment, but also noise, air pollution, climate and socioeconomic factors.

about the writer

Zander Venter

Zander is a spatial ecologist based at the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research in Oslo, Norway. His interests lie in finding creative ways to monitor and visualize urban ecosystem services. His recent research has focussed on the relation between urban green infrastructure, climate mitigation and public health benefits.

about the writer

Vegard Gundersen

Vegard Gundersen, NINA, has long research experience both within social and ecological fields, currently focusing mostly on visitor monitoring methods, nature conservation and management implications of human use of mountain areas. He is trained as forester, did a PhD in urban forestry in 2005, and much of his research is about people’s perception of forest environment, and adaptations of silviculture and management methods for urban woodlands.

about the writer

Erik Andersson

Erik Andersson works as associate professor in sustainability science at the Stockholm Resilience Centre.

This is a vital topic in terms of social justice and environmental quality. I’ve been studying how

My firm conclusion – and I invite responses – that states must seriously consider ‘enfolding-in-law’ (at least constitutionally) a right to accessible greenpeaces, within a reasonable distance/walking time (max. 10 mins) for people. This is particularly needed in high-density and densifying urban context,

Here in Dublin City (popn. c.1.6 milloin), Republic of Ireland, we are fortunate to have – generally and on average – a relative high per capita provision of open, green spaces. But the ‘devil is in the detail’, crude general stats. are insufficeient. That tells little about the Quality and Accessiblity (Proximity to people) of parks and greenspaces. For example, arising from studies undertaken since 2008, we know that there are sizeable pockets of deprivaiton and disadvatagte, aligned to social class. Gap analysis for under-provision not only of greenspace, but also of Play Areas and Urban Trees/Forests also tends to reveal gaps aligned to lower socio-economic groups in society. In addtiion, the failed neo-liberal economic model (virulent, law-of-the jungle capitalism) followed by Ireland during the period 1998-2008, weakened Planning and Development regulations, with developer-led projects the norm.

More recent changes in the government’s Apartment Design Standards have severely reduced the minimum per capita “amenity” space quantum, required of developers of high-density developed. These highly questionable standards override the more strigent standards of the country’s 31 local planning authorities (councils)

In our case (Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council – the municipality where i work as a Landscape Architect), the difference is standard is 66%!

In the Republic of Ireland, we’ve a lot of political lip-service about the importance of parks. The parks and landscape profession is weak and barely present in local government. We’ve a lot of ‘skin-in-the-game’ but little turf. Add that to the fact the Parks+Landscape Service is merely an optional function for local authorities – no statutory mandate (unlike other local services – roads, planning, housing, libraries), and it’s a toxic cocktail of dysfunction. Despite that there is a dedicated band of professionals and advocates fighting to address these existential issues.

For me, the provision Urban Blue-Green Infrastructure is a human rights issue, and one related to social equity question. That iss paramount. A resolved thru mandatory governance in primary law, will be critical, indeed foundational, to making progress.