Although you’d expect an emergency of this calibre to hold the highest ratings of public awareness that unites cooperative mobilisation of global proportions, the 6th mass extinction is quietly happening with little fanfare. (Did you hear the giraffe is listed by IUCN as a threatened species?) Acknowledgement of the unfolding catastrophe does exist, but air time is restricted to headlines of scientific updates, which are both terrifying and framed by an oddly boring medium. Even so, in the year ahead, according to the World Economic Forum, biodiversity loss is the third biggest risk to the world, ahead of infectious diseases, terror attacks and interstate conflict (WEF 2020).

The UN recently warned member nations that, unless drastic measures are taken to curb the ongoing destruction of life-supporting ecosystems, a biologically impoverished planet awaits present and future generations. Since 2017, a decade after reports began suggesting that a mass extinction might be imminent, numerous scientists have begun reporting evidence that the earth’s life support systems have already begun to unravel. Apparently, nature is disappearing at a rate tens to hundreds of times faster than the average of the past 10 million years.

Recent research has shown that birds and insects have declined in significant numbers since the 1970s. Insects play a central role to a variety of processes (pollination, herbivory, detrivory, nutrient cycling) and are important food sources for higher trophic levels such as birds, mammals and amphibians. A large-scale loss of insect diversity and abundance will likely provoke trophic cascades and jeopardize ecosystem services. In September 2019, the most comprehensive bird survey ever conducted in Canada and continental United States reported that 76% of breeding birds (529 species) declined in population 29 percent between 1970 and 2018 (click here to view the figure). The long-term surveys analysed, which accounted for both increasing and declining species revealed a net loss in total abundance of 2.9 billion birds across all species and almost all biomes. Birds are the canaries in the coal mine that is the Earth’s future. Severe declines in both common and rare species indicate that something is wrong.

In the case of birds, and likely the same for other taxa, the causes for continent-scale declines include habitat loss and degradation, unsustainable agricultural practices, pesticides (including, but not limited to, neurotoxic neonicotinoids), climate change and pollution. The authors of the bird study comment that “landscapes are losing their ability to support bird populations”. However, they also highlight the conservation success stories from the same timeframe that brought some birds back from the brink, demonstrating life’s resilience.

Cities are not exempt: everything is connected

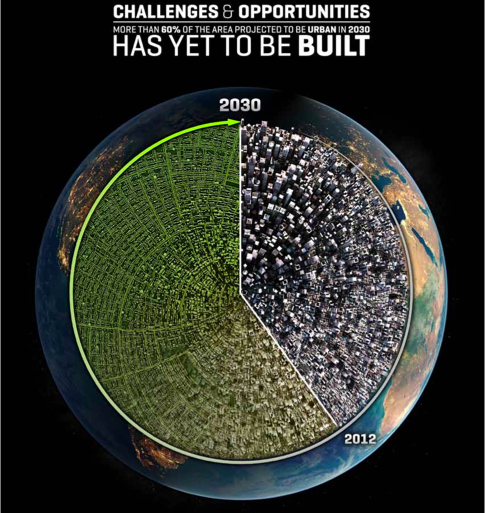

For this essay, I adopt the premise that human settlements have a role to play in addressing the 6th mass extinction. If 60% of the area projected to be urbanised by 2030 had yet to built in 2012 (CBD, 2012), then we have a precious window of opportunity to future-proof cities and their hinterlands to support life. Certainly, cities are only weakly relevant to some of the leading causes of extinction, like overhunting, toxic pollution, and climate change. However, they are not insignificant to other causes, notably habitat destruction, invasion by alien species, and human population growth. This moment is also poignant for its juncture between the UN Decade on Biodiversity (2011-2020) and the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration (2021-2030). Add to this the climate justice movement that has captured the world’s attention, and our window of time is rich in opportunities and rewards.

So, what is the most skilful and effective response or attitude we can adopt to this tragedy? For those of us dedicated to the evolving field of urban ecology, whether thinkers, citizens, designers, policymakers, artists, or practitioners, how do we proceed with our programs and projects when we sense that Armageddon is raging outside our sphere of influence? To set the tone and perspective, I will borrow Greta Thunberg’s analogy that our house is on fire. If we consider biological annihilation akin to our burning house; if we take on board both the evidence and the unknowns; and if we allow ourselves to think outside the box of “expertise” and into the expanse of “we are talented, compassionate, creative human beings”, what might an appropriate response look like?

How to respond when your house is on fire

If our house is on fire and it’s too late for the fire extinguisher, what is an appropriate response? Well, if we want to survive, if we want others to survive, and if we want to emerge with a decent chance of recovery afterwards, then we’ll get out. Not only that, we’ll get out fast, leaving valuables behind and closing doors stop the spread of fire. We’ll raise alarm by notifying the fire department and enlisting all possible help to douse the flames. Mentally, we’ll want to be alert, responsive and careful. Physically, we’ll want to embody vitality and clarity of mind. In short, we’ll do our best. By treating it as an emergency and putting all other concerns and worries to the side, we will dedicate our full presence and attention to the matter at hand.

What might it look like—to dedicate ourselves to the matter of the extinction crisis—when we live in cities? Urban living tends to disconnect people from the natural environment, and the lack of iconic species or ecosystems locally can dampen the proverbial flames beneath our bottoms.

I will use my home as the location for this thought exercise, starting with a brief introduction for context.

Vancouver, BC, is Canada’s 3rd most populous city (2.4 million, Sept 2019). Since 2007, it has consistently been one of the most liveable cities in the world, largely because of its location. The ocean to the West, mountains and fjords to the North, and a multicultural city in between, Vancouver’s high standard of living is closely tied to the quality of its natural environment. As a city, it is also famed for its sleek style of urbanism (“downtown living”, eco-density) and, let’s not forget, for its West coast chillax vibe.

In many cases, and certainly by contrast with other cities, the shiny expectations about this city are true. The quality of life is excellent for many, and the backdrop and access to nature is amazing. Cracks in the veneer have begun to appear, however, partly due to the city’s hasty transformation into a mega-city, with direct implications on its natural environment. The decline in liveability in recent years has been attributed to air quality from wildfires, but also difficult issues like combined sewer overflows, lack of affordability, and polarizing class dynamics.

The land now occupied by the City of Vancouver was once a rainforest and marshland, with over 50 streams that flowed either to the sea or the mighty Fraser River. The oceans and mountains have shaped the humid coastal climate, and First Nations sustained themselves, the land and the water since time immemorial. That changed with exceptional speed after the first settlers arrived in the late 1800s. The seemingly endless forests and innumerable streams and wetlands were cleared, filled and industrialized within a matter of decades, rather than centuries as on the east coast before. Rather than recharging aquifers and supporting local ecosystems, rain that used to be absorbed by the ground or flow through salmon-bearing streams is now intercepted by roofs, drain tile and paved surfaces and directed into an underground pipe network.

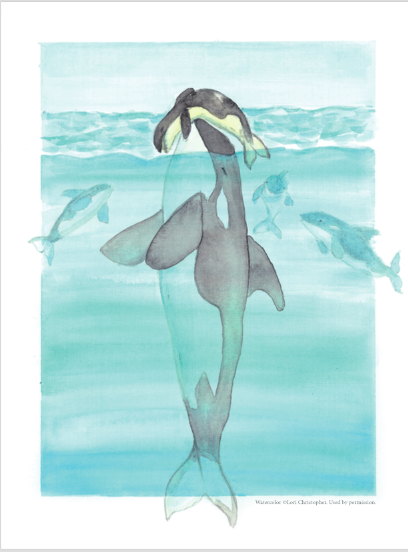

With regards to the extinction crisis, lush and liveable Vancouver is not exempt. Until its ambitious Rain City Strategy is implemented, the city continues to send direct toxic runoff and sewage into the Salish Sea, with massive implications to biodiversity. Shockingly, it appears that one of the region’s apex predators, the iconic killer whale (Orcinus orca), is on track for extinction. Evidence is mounting that the southern resident pod is starving, its population numbers in decline. In 2018, when yet another calf died soon after being born, the pod captured the world’s attention by communicating what is at stake, both for them and for us. Despite public outcry and demonstration, the drivers of this ecocide are not being resolved quickly enough, if at all.

When an ecosystem loses its apex predator, we can expect a ripple effect through all trophic levels of prey, right down to the primary producers (plants). Everything is connected. Compared to the plight of the orcas, however, the signals we receive from the terrestrial environment are subtle, maybe because we don’t notice when something small has gone missing. Still, Pacific Northwest ecosystems are famous for their astounding inter-connectivity, so if a highly intelligent, apex species is at risk then our terrestrial ecosystems are undoubtedly also under pressure.

Since cities are expressions of human dominance over the natural environment, it can be a stretch to imagine how or where to begin restoration efforts. Well, if our house is on fire, then we must act with courage and fearlessness, in collaborative consensus and harmony. In this precious decade ahead, we have no time to lose. It’s valuable to recall that we have much in our favour! We have technology, tools, knowledge and shared language at our disposal. The majority of humanity has “woken up” and aware of the crises at hand, to some degree or other.

In Metro Vancouver, eight municipalities have declared a climate emergency, and a number of ambitious strategies are in process of development and/ or implementation. In these, the term biodiversity is used often but without any detail. For all intents and purposes, I interpret this to mean that biodiversity is a piece of jargon. Recalling the inferno at hand, I will humbly don the warrior’s cloak (as “Captain Well-what-would-you-do?”) and suggest some things we can do to support life in this beautiful part of the world. I will undoubtedly miss some important points and invite you to use the comment section below.

Reconciliation and stewardship

Indigenous peoples (or “First Nations” in Canada) have lived on and cared for the lands and waters since time immemorial, and indigenous stewardship may be the key to global conservation goals. At the time of writing, Canada and B.C. were momentously poised with the opportunity of a generation to demonstrate its acknowledgement of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). Reconciliation in this context honours indigenous rights to territory and tradition, to self-determination and to respect and understanding. Politically it’s been a bumpy road, and I won’t get into that here. Suffice to say that we settlers live on unceded, stolen lands, and we have treated them very poorly. If we were to return these lands and waters to the rightful owners, then restoring them is the least we can do. Fortunately, this will also benefit biodiversity.

Empowering the spirit of respect and reconciliation would also involve exploring the traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and indigenous cultural practices that allowed millennia-old societies to thrive in symbiosis with nature. These time-tested practices were established through ingenuity, creativity, spirituality, ecological understanding and resourcefulness. Allowing First Nations people back to their traditional lands, supporting the revival of traditional knowledge and practices, and/ or restoring degraded lands can heal the land and all people. In this era of nature-deficit-disorder and loneliness, connecting with nature and with other beings will significantly enhance individual and social well-being (however urban). Whether joining a conservation group, adopting a local green space, or connecting with First Nations on indigenous-led campaigns, we have much to gain.

Biodiversity-led landscapes

Building on a foundation of reconciliation and respect for indigenous tradition and knowledge, an appropriate response to the extinction crisis will also involve multi-functional landscapes. This means that every surface is relevant to both biodiversity and humans, while also repairing links to the damaged hydrological cycle, improving air quality, providing shade, etc. With regards to plantings, cultivated forms lacking value for wildlife will be replaced with species or cultivars that provide food that is nutritious. For example, the red-flowering currant is an early flowering shrub that provides nectar for hummingbirds fresh in from migration and for newly awakened bumblebee queens. The City of Vancouver and partners have been installing pollinator gardens, often featuring nest boxes and wildflower meadows, for demonstration and education. Someday, let’s aim for healthy and viable pollinator habitat to be everywhere!

Similar to plant selection, the management and maintenance of landscapes must take into account the nesting requirements of native bees, of which there are nearly 500 in BC. For example, willows are essential host trees for certain specialist species of solitary mining bees, conifers provide resins for bees that construct resin nests, and elderberry is great for stem nesting bees. Wildflower meadows designed for native pollinators must ensure the soil specifications and maintenance regime are all aligned with nesting needs, and that they take entire life cycles into consideration. It goes without saying that pesticides are not appropriate during an extinction or a climate crisis, especially given the “evidence that these treatments have little to no benefit in many crops.” One of the province’s youngest societies, the Native Bee Society of BC, is assembling resources that identify the needs of native pollinators, e.g. , soil specifications.

Replacing hard with soft

Heavily manicured landscapes must be re-oriented to the needs of healthy ecosystems and healthy communities. Parks and green spaces featuring expanses of lawn must be diversified with mosaics of habitat, including groves, meadows, ponds, wetlands and constructed ecosystems like bioswales and rain gardens. Native trees and shrubs will be planted to benefit native pollinators and birds. Wetlands must be restored, of which the massive dividends to biodiversity will also benefit access to nature, climate resilience, carbon sequestration and much more. There are countless opportunities to de-pave the hardscape of the region, what with its high water table and proximity to salty, fresh and brackish waters (salt marsh, mud flats, peat bog, riparian streams, rivers). The sky’s the limit, so to speak!

As sea level rise weakens Vancouver’s recreational sea walls, these hard surfaces can be replaced by floating paths that allow for restored intertidal zones beneath and associated habitat for shellfish, clams and more. The terribly polluted waters of False Creek can be improved with floating vegetated islands designed for phytoremediation, i.e., planted with species that remove, transfer, stabilize, and/or destroy contaminants. We must also restore and maintain inter- and subtidal estuarine habitats, like eel grass, which provide important spawning and nursery habitat for numerous fish (and therefore serve as important feeding areas for marine birds and mammals). Such interventions will concurrently improve water quality by trapping sediment, pollutants and nutrients.

Reducing combined sewage outflows is an urgent priority of the moment for the City of Vancouver, and much hope is hinged on the Rain City Strategy, which aims to capture and clean 90% of urban stormwater. In areas where “reverse engineering” and de-paving the landscape is not feasible, multi-functional green infrastructure must be implemented that not only fulfils the requirements of water sensitive design but also provides habitat for wildlife, beautiful nature experiences for residents, thermal comfort and improved air quality, etc. All that being said, let’s not forget to refer to indigenous practices and technologies before seeking high-tech solutions from other parts of the world.

Engaged citizenry must inform political will

We have a huge range of options for speaking on behalf of beings without voices and rights. As individuals, we can strive to be ethical consumers and divest out of life destroying institutions. We can connect into supportive communities by campaigning on issues close to our hearts. We can express our wishes by contacting political representatives and signing petitions. As citizens of the earth, we might heed the call of former UN climate chief who recently stated that “civil disobedience is not only a moral choice, it is also the most powerful way of shaping world politics”.

We can support the development and adoption of effective policies, too. For example, the Ecocide Project is working to establish ecocide as international crime, alongside other crimes against peace of (i.e., genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, crime of aggression). Making ecocide a crime could serve as a brake on the few companies responsible for the majority of destruction while reaping profits. We can each contribute to halting reckless industrial activity by discouraging government ministers from issuing permits, banks from lending, investors from backing it, and insurers from underwriting it. As such, we can help weaken the infrastructure that silently sanctions acts of large-scale environmental destruction.

Ten years ago, the world’s governments pledged to stop subsidizing activities that drive species to extinction, opening the UN Decade on Biodiversity. This has had little effect. Meanwhile, trillions of dollars are awarded annually for subsidies that contribute to the drivers of extinction! In a recent paper, Dempsey and colleagues (2020) discuss methods for holding governments to account, namely subsidy accountability. They envision interdisciplinary teams working together to track subsidies and to forecast the environmental and social effects of their redirection or elimination. “To advance transformative economic change, we need to build country-specific lists of policies in need of reform and, crucially, to amass the political power necessary to persuade governments of all stripes to implement such changes. Big, public money is out there. We need to redirect these funds towards efforts that support ecologically sustainable economies and full pockets for nature” (p. 2).

In closing

We have a choice on the story lines we wish to adopt. In our minds and collectively, we have an opportunity to envision and manifest the world we wish to inherit. Nature will never give up on life. Just as wildfires of apocalyptic intensity burn out and new life emerges, we are part of the dance of life and our actions do have consequences. The truth is, we may read countless papers and reports, but we may never truly know what the future holds. To my mind, this lack of absolute certainty, combined with unprecedented phenomena, implies that we are enlisted in an ethical, if not spiritual, dilemma. Whether or not the orca benefit from our de-paving the region and restoring fragmented habitats and food webs is, in a way, beside the point. The resilience of life is forever affirming, and this can be our cue. On the one hand, any action other than freezing like a deer in the headlights is better than nothing. On the other, if we have the wherewithal to remain present, alert, kind and compassionate, inside or near a raging inferno, we may find that taking care of ourselves and caring for other beings are one and the same. Think global and act local. Life will thank us for it.

Christine Thuring

Vancouver

References

Ceballos, G, Ehrlich, PR and Dirzo, R. 2017. Biological annihilation via the ongoing sixth mass extinction signaled by vertebrate population losses and declines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (30) E6089-E6096 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1704949114

Dempsey J, Martin TG, Sumaila UR. 2020. Subsidizing extinction? Conservation Letters 13. DOI: 10.1111/conl.1270

Figueres, C and Rivett-Carnac, T. 2020. The Future We Choose: Surviving the Climate Crisis. Knopf Publishing Group. ISBN 0525658351

Gauger, A., Rabatel-Fernel, MP., Kulbicki, L., Short, D. and Higgins, P. 2013. The Ecocide Project: Ecocide is the missing 5th Crime Against Peace. Human Rights Consortium, London. ISBN 978-0-9575210-5-6

Macy, J. and C. Johnstone. 2012. Active Hope: How to face the mess we’re in without going crazy. New World Library, Novato CA.

Román-Palacios, C. and JJ Wiens. 2020. Recent responses to climate change reveal the drivers of species extinction and survival. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1913007117

Rose, C. 2019. Devastation in the Skies. Wingspan. A publication of the Wild Bird Trust of British Columbia. 8-11 https://wildbirdtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Wingspan-2019-Fall-Winter.pdf

Rosenberg, KV., Dokter., AM, Blancher, PJ., Sauer, JR., Smith, AC., Smith, PA., Stanton JC., Panjabi, A., Helft, L., Parr, M., Marra, PP. 2019. Decline of the North American avifauna. Science. 366 (6461): 120-124. DOI: 10.1126/science.aaw1313 https://science.sciencemag.org/content/366/6461/120

Watson, J. 2020. Lo-tek. Design By Radical Indigenism. Taschen.

Whyte, D. 2020. Ecocide: Kill the corporation before it kills us. Manchester University Press. ISBN: 978-1-5261-4698-4

World Economic Forum. Jan. 2020. The Global Risks Report 2020. 15th edition.

Wonderful important article / essay I have come to read (I’m in Nova Scotia) because Christine Thuring is now #3 TMX Tree Top protestor on Day 2 Aug. 22, 2020.

Thanx/Merci/Megwitch

Admin of the Canada Waking Up the Masses ( 2014-2020)

& Save the Bay of Fundy Heritage group