One of my favourite bedtime stories when I was little, was about two field mice, Millie and Tom. The poppy flower in the cornfield overheard Tom whispering a secret in Millie’s ear that the day after full moon, at 14h00 they would get married. The poppy flower told the little secret to the corn, the bellflowers, the wind and the sparrows, who said we will make the bells sound and sing for them on that day. And so it was, when the clock stroke 14h00, the breeze was blowing confetti of grass, the sparrows were singing and the bellflowers were ringing. At the end of the day Millie said to Tom: “it was a wonderful wedding, but I wonder who has told our secret?” Tom said: “it is not possible to keep secrets here, the flowers and the corn have ears.” And so many times I looked at the cornfields, their flowers and birds with a sense of admiration for their ability to hear our stories.

Another sound of nature that humans have hardly noticed is the communication between trees. Backed by a growing body of scientific evidence, Peter Wohlleben, author of the book, The hidden life of trees: what they feel, how they communicate, explains how trees are connected to each other through underground fungal networks, through which they share water and nutrients and communicate. At an international conference on forests for biodiversity and climate change in February of this year in Brussels, he said: “We do not know how many species we have in our forests. There are hundreds of thousands of the smallest creatures like bacteria, which form an indispensable part of the ecosystem. If we harm forests we don’t know what we lose. We have to be extra careful and not log more”. Most bacteria are decomposers that convert energy in soil organic matter into forms useful to the rest of the organisms in the soil food web. Some can even break down pesticides and pollutants (United States Department of Agriculture). Effective protection and management of forests and soil based on understanding the roles of all parts of the ecosystem are the most powerful weapons against biodiversity loss and climate change.

Ants are wonderful creatures, often admired for creating peaceful and highly productive societies. What you may not know is that ants are very strong ecosystem indicators, because they adapt quickly to their environment, interact with many other species, for example by creating homes for fungi and micro-organisms in their nests, and influence important process such as nutrient cycling and seed dispersal (Ensia, 2019). To learn more about the results of restored landscapes altered by agriculture production or mining, researchers distinguish different ant species in undisturbed lands and newly revitalised lands, finding that there is a strong association between ant species and environmental attributes such as the humidity of leaf litter on the ground.

Another fascinating but invisible natural phenomenon is found under water. Kelp forests, consisting of large brown algae, are marine environments that provide food and shelter for species at all levels of the food web and sequester vast amounts of carbon. Researchers Dorte Krause-Jensen and Carlos M. Duarte (Nature, 2016) estimate that around 200 million tons of carbon dioxide are being sequestered by seaweed every year, about as much as the annual emissions of the state of New York. However, they are increasingly threatened by climate change, overfishing, and harvesting.

Bat Conservation International has conducted a two-year experiment in cornfields in Southern Illinois to study the role of bats in agricultural production. The study confirms that bats play a significant role in combating corn crop pests, preventing more than $1 billion in crop damages around the world every year. Bats provide additional value to agriculture by suppressing toxic fungi and reducing the necessity for costly insecticides.

These are only a few of many examples that show the extraordinary wisdom and power of nature and how much we can learn from the natural world that surrounds us. However, in today’s highly urbanised world very often the voice of nature is not heard or not listened to…

Why we need to listen to the voice of nature, more than ever before

The world is watching the 6th extinction crisis, with an average decline in populations of birds, fish, mammals, and amphibians of 60 percent since 1970 (WWF Living Planet Report, 2018). The number of plants that have disappeared from the wild is more than twice the number of extinct birds, mammals and amphibians combined. In response, the global community is preparing to make path-defining choices for the future of our planet. We are embarking on the UN Decade of Restoration (2021-2030), the year 2020 is the UN’s International Year of Plant Health, and 2021, the 196 countries party to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity plan to gather in Kunming, China to decide on a new agreement for the global protection of nature until 2030. Nature is making the headlines in our news like never before, as we are losing forests, soils, wetlands, oceans and all the precious natural systems humans depend on. It is more clear than ever that this generation is the one that has to turn the tide.

Protecting biodiversity should not only focus on pristine habitats in remote areas, but on creating space for nature in the places where we live. If we bring this thinking into our increasingly urban world and the growing momentum for greening and reforesting, it is important to consider for which animal, plant and tree species we create a home in our city streets, roofs, parks and backyards. Cities do not only harbour a significant fraction of the world’s biodiversity, but can also be made more liveable and resilient for all living creatures, through nature-friendly urban design, learning from nature.

Throughout the world, natural ecosystems in and around cities continue to be fragmented or disappear as a result of urban expansion and development, with only modest regard for their function and contribution to the regional community and economy. Natural infrastructure and integration of biodiversity in urban planning, such as pocket parks, urban farming, green walls, tree planting and daylighting of rivers, offer innovative and cost effective solutions that improve quality of life and climate resilience.

One of the London boroughs, Brent, decided last year to create a seven mile long “bee corridor” of wildflower meadows in parks and open spaces to boost the numbers of pollinating insects. More than 97 percent of the UK’s wildflower meadows have disappeared in the last 75 years, but many butterflies, bees, dragonflies and moths rely on these flowers (Powney et al, 2019).

The deep connections between nature and human health have been demonstrated extensively in research.Khoo Teck Puat Hospital in Singapore has applied this knowledge by integrating plants and nature in its design, on the basis of the belief that people relax and heal faster with views of trees and plants, and when hearing birdsong (L. Jones, 2020). The hospital has balconies, planters, waterfalls, green walls, roof gardens and an organic food garden with over 100 fruit trees where local volunteers grow food for the kitchens. This creates the feeling that the hospital is in a forest and provides natural ventilation and has its own microclimate.

Nadezhda Kiyatkina is a researcher and activist and writer for The Nature of Cities, who shared a story about the Cherished Meadow project in Moscow, describing her experiences with the development of a park on a three-hectare plot of land that housed car sheds previously called “barren land”. What is unique about the project is the interdisciplinary cooperation between biologists, architects, landscape architects, and the involvement of residents and local authorities. Residents were asked about their wishes for the landscape near their home, and the three main reasons they gave in response to the question “Why do you go to parks?” were walking with children; meeting other people; and having the possibility to admire and watch nature. 40% of respondents come specifically to listen to the birds sing. As a result, in the design of the park, lawns were ruled out, only native plants were used, bushes were selected based on their quality to provide nesting space for birds, and paths were made convenient not only for the pedestrians, but also for the insects. It became a success story for people and nature, winning the support of over 3000 residents, receiving two architecture awards, and gaining the support of the local authorities.

Field flowers, or “akkerbloemen”, as we call them in Dutch, are among the most threatened plant species in The Netherlands. Their diversity has evolved over thousands of years, but many that were growing in abundance when my mother was a child, living in a small South-Dutch village in the countryside of Limburg, have disappeared. Others are highly threatened, like the poppy flower, camomile and cornflower. Our current agricultural practices completely changed the soil, fertilisation, humidity and temperature. Combined with the use of pesticides and loss of biodiversity-rich field margins, the wild flower diversity in the Netherlands disappeared in less than a century. In 1995 in Limburg, Natuurmonumenten, one of the Dutch nature conservation organisations, bought an estate with agricultural fields and dedicated the land to the protection of field flowers, creating landscapes full of insects, butterflies, life and diversity to enjoy. It would be of tremendous value if farmers could, with support of the EU Agricultural funds, create field margins with indigenous field flowers across Europe (Puur Natuur, Natuurmonumenten, Zomer 2019).

The Tana Delta in coastal Kenya, one of the most important wetlands in Africa, has been facing the growing pressure of commercial crop production of sugarcane, maize, rice and jatropha (for biofuels), as well as plans for the development of a port for further exploiting the natural resources, putting at risk the livelihoods of people and wildlife. Serah Munguti, finalist of the Tusk Award for Conservation in Africa, 2017, has initiated the Tana Delta Sustainable Land Use Plan, which helped in developing community livelihoods projects in the Tana Delta, supporting farmers, fishermen and pastoralist communities to make a transition to sustainable production methods, while increasing their income from crops, honey, fish farming and cattle. She believes that “nature matters to all of us, it is our food, medicine, fuel and clothes and we should all do our part in conserving the natural environment”. Conservation of the Tana River Delta is currently being enhanced through a forest landscape restoration project funded by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) through the United Nations Environment Programme and with Nature Kenya as implementing partner. The project implements some elements of the delta’s land use plan, which provides for land and water allocation and will enable local communities, civil society, and national and county governments to come up with policy and institutional frameworks to implement restorative land use initiatives.

How can we reconnect with nature?

In 2018 the Wall Street Journal raised awareness of growing “plant blindness” in the United States, which means that fewer and fewer scientists are able to identify plants. There is less interest among students in studying plants, as they shift towards parts of plant science that have commercial applications, such as molecular biology. This raises the question of whether students can have an adequate understanding of nature without knowing what makes it up. Organizations such as the National Park Service and Bureau of Land Management cannot find enough scientists to deal with invasive plants, wildfire reforestation, and basic land-management issues, and prompted botanical gardens around the nation to raise the alarm (WSJ, 2018).

Jane Goodall points out that we have broken the link between intellect and wisdom. Nature has tremendous wisdom, we can learn so much from the most important mind and voice of the planet. It can give us the ideas, creativity, energy, cooperative spirit and joy that can trigger the transition we need to live in harmony with our natural environment. Thankfully, there are some truly wonderful initiatives around the world that help us to hear, see and enjoy the magic of nature.Leipzig responds to the demand of citizens for more green in the city, to improve air quality and reduce noise. One of the ways to do is by increasing the number of urban trees. I noticed when walking near the railway station that many of the trees had a square copper plate with a message and the names of citizens. Through the “Baumstarke Stadt” (“Tree Strong City) initiative, set up by the City of Leipzig in 1997, which gives private people and businesses the opportunity to donate a minimum of 250 euro for the planting and maintenance of one or more trees (“tree adoptions”— Baumpatenschaften), 5,000 trees have been planted, adding 500 trees every year. Part of the beauty is that the tree is dedicated to individuals, and is often planted for a special occasion, like a wedding, anniversary or the birth of a child.

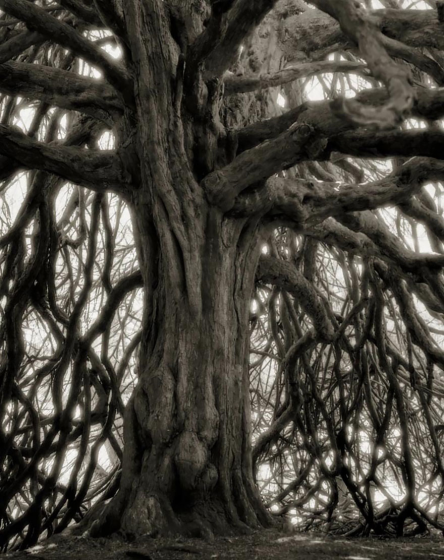

Beth Moon has made remarkable photos of the world’s oldest trees, which give us the power to connect with time and nature, in ways so much greater than ourselves. In 2018, the New York Times dedicated an article to the ancient cedar trees of Lebanon, some of the oldest trees have survived for more than 1,000 years and are World Heritage. They flourish on moisture and cool temperatures, an ecosystem unusual in the Middle East. Climate change is bringing critical challenges to this part of the world, impacting agriculture, water and food supplies and livelihoods. If climate change continues, in the future, cedars will be able to thrive only at the northern tip of the country, where the mountains are higher. The trees that are so symbolic for the country that they are in the center of the Lebanese flag, and existed for thousands of years, are highly threatened. Some years ago, Lebanon’s Agriculture Ministry started, with support of German, Korean and Swedish environmental and development funds, a landscape restoration project to plant 40 million trees, including cedars, aiming at increasing forest cover from 13% to 20% till 2022. Growing cedars back is not an easy task, as they grow slowly, bearing no cones until they are 40 or 50 years old, hopefully these restoration efforts will help to win the race against the climate change clock.

We all know that wolves hunt for their prey, but how wolves can give life to many species is less well-known. In 1995, wolves were reintroduced in Yellowstone National Park, after an absence of 70 years. Vegetation had been grazed away by deer, which had no predators. When the wolves came back, the deer started to avoid valleys and gorges, and these areas started to regenerate immediately, with rapidly growing forests and a great increase in songbirds, migratory and beavers. This created new niches for other species, such as otters, ducks, fish, reptiles and amphibians, more mice and rabbits, leading to an increase in birds of prey, such as hawks and eagles. The bear population also started to rise, because of the increase in berries. The wolves also changed the rivers, reducing meandering, making the channels narrower and reducing erosion, as the forests stabilised the rivers, creating wildlife habitats.

Many rivers have been depleted in most parts of the world. Forty years ago, Bangalore had over 1,020 ponds and lakes and 3 perennial rivers. Today there is hardly a trace of these rivers, as they have all been built over. Only 82 lakes and ponds exist, and about half of them are covered in sewage. A very inspiring leader, Sadghuru, a yogi from India, has mobilised millions of people through one of the largest ecological movements on the planet, a nation-wide campaign “Rally for the Rivers” aiming to implement long-term policy changes to restore India’s depleted rivers and deserted land. Four percent of Indian rivers are glacier-fed, the rest are forest fed. It is recognised that bringing back the forests and restoring the organic content of soil through agroforestry farm management practices will revive and slow the flow of the rivers, create water reservoirs in the soil, and improve the life of people, animals and plants. To turn this into practice, we need cross-regional policies and cooperation as rivers do not stay within country and regional borders. Over 70 percent of the land in India is owned by farmers, and according to Sadghuru, they need support to move from crop-based to tree-based agriculture along the rivers, in a way that marries ecology and the economy. People will only be involved if they benefit economically. The experiences of 70,000 farmers using forest-based agriculture through “Rally for the Rivers” have proved that income from crops can go up by 3 to 8 times. This transition will also increase the ecological quality of the soil and rivers (World Economic Forum, Platform for Shaping the Future of Global Public Goods, there is no planet B, 2019).

Let’s ask ourselves what we can we do for nature

The world’s economic wealth and profits have been created at the cost of the natural world and indigenous and marginalised communities who have always been the stewards of these natural systems. If we go back to the roots of the word corporation, we will see that companies initially developed with environmental and social aspirations at an equal footing with economic gain. It is time for business to go back to its founding principles and make our natural world truly part of the equation by developing regenerative business models and by making natural and social capital part of our economic system.

Listening to the words of living legend, Sir David Attenborough, humans are the mayflies of evolution, in comparison to the complex life forms that first appeared in the oceans around 540 million years ago. But we have evolved into the planet’s most dangerous predator. Considering our dependence on nature as our life support system, it is high time that we listen to the stories nature is telling us, to learn from its millions years of wisdom and to give a voice to the voiceless. Joaquin Phoenix stood up for the voiceless in his Academy Award speech for Best Actor in the film “The Joker”, saying that: “no one species has the right to dominate, control, use and exploit another with impunity. We have become very disconnected from the natural world and plunder it for its resources”. He added that “human beings are so inventive, creative and ingenious, and when we use love and compassion as our guiding principles, we can create systems of change that are sentient to all living beings and the environment”.

As the stories from all over the world demonstrate, the wisdom of nature is the lifeline for our future and our most important ally in finding the pathways to transform the harmful exploitation of natural resources into a regenerative system that balances human aspirations with a healthy planet. In addition, it is time to ask ourselves, what can we do for nature?

Chantal van Ham

Brussels

References

- Lyanda Lynn Haupt, Mozart’s Starling, 2017

- Lucy Jones, 2020, Losing Eden: why our minds need the wild, Allen Lane

- Peter Wohlleben, The hidden life of trees: What they feel, how they communicate, 2015

- A healing space, Creating Biodiversity at Khoo Teck Puat Hospital, Alexandra Health, Singapore

Add a Comment

Join our conversation