about the writer

Naomi Tsur

Naomi Tsur is Founder and Chair of the Israel Urban Forum, Chair of the Jerusalem Green Fund, Founder and Head of Green Pilgrim Jerusalem, and served a term as Deputy Mayor of Jerusalem, responsible for planning and the environment.

Introduction

Following the Nature of Cities Summit in June 2019 in Paris, a group of us continued the discussion that began in the seed session “Greening Water-Scarce Cities.”

Diane Pataki, Peter Schoonmaker and Naomi Tsur, who had put together the session, were joined by Paul Currie and Mario Yanez in a series of cyber meetings, through which we have attempted to collate and synthesize the creative ideas that had been presented at the seed session into an ethical code for water. It is our hope that this can become a useful basis for diverse parties and institutions in their efforts to address the challenges of water in our current climate crisis, in which no area is unaffected by changing water patterns.

We asked David Maddox to enable us to present our initial document as a theme for a TNOC Round Table Discussion, and look forward to seeing your comments, criticism, and in general addenda and corrigenda.

You, our fellow contributors and readers of TNOC are the first to see this document. It can be used by all, of course, but it is our hope to present it in 2021 at the World Water Forum in Dakar.

It goes beyond the scope of cities, but can certainly be a basis for cities to develop policy, educational programs and infrastructure. The initial responses to the code have been provided by the participants in the seed session.

Naomi Tsur, Jerusalem

Mario Yanez, Lisbon

Diane Pataki, Salt Lake City

Peter Schoonmaker, Portland

Paul Currie, Cape Town

Roundtable question: Water is essential to life. For many it is inaccessible, while others take it for granted. We propose here a code for the ethical use of water in cities. What works? What doesn’t? Would you use this code to transform your city?

The ethical basis for water rights and obligations in cities

Background and Motivation

After a workshop held at “The Nature of Cities Summit” (Paris 2019), a group of TNOC contributors committed to meeting regularly in order to establish an ethical basis for water use and management. This document is a preliminary draft of our understandings, hopefully a basis for many conversations and policy discussions as more and more stakeholders address the principles laid out. The document also represents a simple guide for ethical actions with regard to water.

Acknowledging that there have been many explorations of water ethics, this document sets out some succinct observations and ethical principles related to urban water use and management and offers considerations for ethical water actions.

Declaration

It is a universally accepted truth that:

- Water is the basis for all life on earth

- People and nature have a universal basic right to clean, safe water

- Ecosystem functions provide a wide range of water-related services (to people and nature)

- More than half of the world’s freshwater supply is currently allocated for human activities

- Neither people nor nature are universally receiving their rights to water

- While many experience water excess, many experience water scarcity

- Climate crisis is changing hydrosocial cycles in fundamental ways

- Almost all urban areas import water, with potential impacts on upstream and downstream ecosystems

- All urban activities have an embodied water footprint

- There exist many ecological, social and technical solutions to improve water access and management

- The sourcing, treatment and distribution of water have energy and material implications, with wider environmental impacts

- There is a conflict of interest between supply-driven business and the need to reduce consumption

- Where water is privately controlled, there is risk of exclusion from water access

- There is a mismatch between administrative boundaries and watershed areas

- People are entitled to use water in manners which express their needs, cultures, values, and activities

- People have an obligation to use water responsibly

- All are responsible to protect and regenerate the integrity and functioning of water cycles

- These obligations and responsibilities will only be fulfilled through the commitment and participation of National and Sub-National Governments, Civil Society, Academia, the Private Sector, Communities, Conveyors, and Individuals.

Commitment

I as a water user will commit to:

- Understanding my local and global water cycles

- Appreciating that natural fresh water is finite in global supply

- Conserving water and using it mindfully

- Being cognizant of and responsible for the upstream and downstream impacts of our actions

- Reusing water multiple times whenever possible (cascading)

- Reserving potable water for drinking and bathing

- Preventing household pollutants from entering the water cycle

We, as water suppliers or conveyors, commit to all of the above, and also to:

- Taking a watershed perspective

- Educating ourselves, peers, residents, and children about how the water system works and our roles in it

- Investing in consistent data collection, analysis and sharing

- Investing in a hierarchy of water supply types, which allocates and cycles potable water, greywater, and blackwater appropriately (at multiple scales)

- Preventing agricultural and industrial pollutants, and untreated wastewater from entering socio-ecosystems

- Pricing water services effectively to incentivize stewardship while ensuring that the water system remains intact and that people’s basic needs are met

- Operating in good faith when engaging with local communities

- Participating in multi-stakeholder water governance processes

- Contributing and adhering to water action plans and other policy instruments

We, as government, business and civil society at all levels, commit to all of the above, and also to:

- Enabling governance of water which ensures stewardship and regeneration

- Ensuring that everyone has access to clean water for drinking and bathing

- Ensuring that water management is not monopolized, nor driven primarily by economic gain

- Preparing for climate crises by adopting resilience strategies and appropriate infrastructures

- Mandating swift action in the face of impending water crises

- Ensuring collection and open dissemination of information, data, and best practices for water management and stewardship

- Facilitating and investing in creativity, innovation and experimentation for appropriate technologies, and regenerative infrastructures and practices

- Developing and enforcing suitable water policies and action plans for every city through multi-stakeholder engagement

- Managing conflicts in water provision

- Ensuring that diverse socio-cultural values, needs and practices regarding water are acknowledged and accommodated.

Way Forward

Our manifesto!

Inundated with ideas!

Now you should join us!

As a working document, we invite colleagues to comment, add to, and embrace this ethical code for water, for presentation and adoption at the World Water Forum 2021 in Dakar, Senegal.

It’s universal,

Water. Too much. Too little.

But a right for all.

Would you like to join a global team that takes this forward? If so, please do leave a comment and email us at [email protected]

Not enough? Too much?

Our water manifesto:

Be responsible

about the writer

Mario Yanez

Mario Yanez is dedicated to envisioning and inspiring a transition toward life-sustaining, regenerative human communities. As a whole-systems designer, he is working globally at various scales, implementing productive landscapes and ecosocial systems. As a scholar-practitioner, he is researching complexity and pathways toward cultivating wholeness in society and economy.

about the writer

Diane Pataki

Diane Pataki is a Professor of Biological Sciences, an Adjunct Professor of City & Metropolitan Planning, and Associate Vice President for Research at the University of Utah. She studies the role of urban landscaping and forestry in the socioecology of cities.]

about the writer

Peter Schoonmaker

Peter Schoonmaker leads the outdoor education program at American Community School Beirut, and is president of Illahee, a non-profit organization focused on designing new models for cooperative environmental/social/economic problem solving.

about the writer

Paul Currie

Paul Currie is a Director of the Urban Systems Unit at ICLEI Africa. He is a researcher of African urban resource and service systems, with interest in connecting quantitative analysis with storytelling and visual elicitation.

about the writer

Gloria Aponte

Gloria Aponte is a Colombian landscape architect who has been practicing for more than 30 years in design, planning and teaching. She lead her own firm, Ecotono Ltda., in Bogotá for 20 years. She led the Masters program in Landscape Design at Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana, in Medellín. She is a consultant and belongs to "Rastro Urbano" research group at Universidad de Ibagué, and also the Education Clúster at LALI (Latinamerican Landscape Initiative).

Gloria Aponte

Talking about how the water system works, it is well known and understood that water flows in a cycle, which varies according with geographical and meteorological particularities of each place. Thus, the point where the water cycle meets the earth becomes quite important. How does land receive water? Through a pervious surface that is home for water? Or an impervious surface that tends to reject it? In the first case, slow release assures a balanced supply, while in the second storm water quick release will be the result.

One example of the first case are the so called paramos, a unique ecosystems located in the tropical area but on very high mountains between 3.000 and 4.500 m; mostly in the Andes in South America and Costa Rica. Paramos guarantee a very convenient water disposal equilibrium, regulating the water flow and avoiding soil erosion; they have been considered “water factories” because of the permanent disposal they provide. Additionally, their soils also have more capacity for fixing CO2 than soils of other ecosystems, which is an additional contribution to face the present global crisis of climate change.

There are just six areas in the world that have paramos ecosystems and half of them are located in Colombia. In this country there are 37 paramos areas, and those provide the 70% of the water supply for the population and activities. That is the reason why Colombia has been classified as one of the richest countries in water, counting with a very wide and abundant hydric net.

Historically paramos were even revered by native pre-Columbian groups, that had a very close relationship whit nature and deeply respected it. Nevertheless, in last decades and mainly at present, paramos are menaced by agricultural and mining activities that increase progressively in their surroundings.

In the national context, paramos have been considered an important heritage but just in 2018 the law (Law 1930) to protect them was declared when it was visualized that climate change could make them disappear. The vegetation on Paramos ecosystems is quite outstanding and it becomes lower on higher altitude. The most representative is frailejon, that reaches up to ten meters high, growing only one centimeter per year.

Photo: Valentina Hidalgo, Msc. In Landscape design

The Colombian public ministry asked UNESCO to declare paramos a World Heritage, for the first time in 2017. The petition continues at present, in order to formalize that deserved designation. Last internal national movements about had taken place during pandemic time, in August and September 2020, to once again file the petition with UNESCO.

Paramos are the origin of the water we enjoy in cities, so we urban inhabitants must apply the Code of water, in order to guarantee the water cycle in best quality and assure that ourselves, peers, residents, and children contribute in that sense.

When something is scarce it becomes more valuable, and liability is proportional inverse to availability. As the naturalist George Schaller says: “we have to change our cultural relationship with the natural world”.

about the writer

Carmen Bouyer

Carmen Bouyer is a French environmental artist and designer based in Paris.

Carmen Bouyer

In my view, the points that are presented to structure this commitment could be boiled down a bit more and reorganised to be more easily legible. For instance, I would engage more easily with The declaration section that introduces the document if it was structured by themes: Water in general (1.)(2.)(5.), Climate (7.), Ecosystems (3.), People (4.)(11.)(6.)(15.)(12.)(13.)(14.), Urban issues (8.)(9.), Solutions/Obligations (10.)(16.)(17.)(18.).

In the Commitment section, I would also shuffle the numbers a bit. In the first part “I as a water user will commit to”, I would have the commitments listed in that order that feels more intuitive to me: Understand (1), Being conscious (4.), Appreciate (2,), Conserve (3.), Reuse (5.), Reserve (6.), Prevent (7.). And in the third part “We, as government, business and civil society at all levels, commit to all of the above, and also to” I would organise the points in this order: Access to clean water (2.), Managing conflicts (9.), Governance of water (1.), Water management (3), Preparing for climate crises (4.)(5.), Water policies and actions plans in cities (8.), Open dissemination of information (6.) Ensuring diversity of water based socio-cultural ways (10.), Investing in innovation (7.)

Thinking of transforming my city, Paris, by using those guidelines I wouldn’t know where and how to start. As a citizen I feel I have very little access to policy making regarding water (except by electing representatives every other year) and so wouldn’t know to whom to address the Code here. A code that would have to be translated in French and accompanied by examples of actionable ways showing how those ideals can be applied locally.

But even though I am not in a position where I can directly transform my city regarding water ethics, I can commit to the code as an individual water user and I can support that movement forward and raise awareness through my artistic practices. This ethical code for water can absolutely be applied to an art practice. It asks creatives to create symbols, images and experiences that can convey a strong ethic regarding water, ecosystems and people, creating ways to sense and respect the presence, wisdom and value of water everywhere. It asks artists to use materials that are fully non toxic, not polluting the waterways, and non-water intensive. To do so in a radically honest way would totally change the way art looks and feels in my country.

about the writer

PK Das

P.K. Das is popularly known as an Architect-Activist. With an extremely strong emphasis on participatory planning, he hopes to integrate architecture and democracy to bring about desired social changes in the country.

PK Das

There is urgent need for the recognition of all the natural and environmental conditions and their mapping through a well-planned participatory program. An open mapping and database are fundamental to an understanding of the natural resources and their sharing– an imminent objective of sustainability. Further, the democratization of planning is a significant step too in the struggle for rejuvenation and revitalization of all the natural assets and areas, indeed of water, waterbodies and watercourses, for the successful achievement of the very objective of sustainable urban development.

Historically, the waterbodies and watercourses, including rivers across Indian cities have been turned into sewer and sloid waste disposal channels. Most watercourses have been formalized by governments as sewage channels by constructing impervious concrete walls along both edges in order to “contain the filth” and to gain land through landfilling the wetlands in order to promote real estate interest. In many instances, the beds of the watercourses have been concretized too. As a result, the symbiotic relationship that exist between water and land are severed. Also, water and the surrounding land are starved of their nourishment and severed of the multitude of ecological services that that they both individually and together provide. Such rampant destruction of nature and the natural conditions have led to an alarming state of unsustainable urban development with devastating floods and submergence of vast areas– being just one of the many threats that we increasingly experience in cities world over, including India.

City planners all along have refused to recognize the need and importance of building with nature, including integrating natural areas in the development plans. The vast stretches of watercourses, waterfronts, creeks, wetlands, mangroves, natural flora and fauna, coastal edges, hills and forests are excluded and being treated as dumping grounds, both physically and metaphorically. Governments and planners are affected by a build-more syndrome. A syndrome that has been systematically promoted and inflicted under the principles of privatization and the free- market oriented development that is built upon just one objective, i.e. to fast track financial turnover and profit at any cost through private initiative– reflected in the ruthlessness of capital markets and the development ventures that is increasingly colonizing public assets, including attacks on the natural areas through indiscriminate landfilling. Governments behave the same way by directly undertaking landfilling works or legitimizing the effort by private agencies. Over the years, we have failed to evolve methods for evaluating environmental values and its benefits as being an integral aspect of development economy.

Under such dominant socio-political climate, people’s understanding of nature and the environment and their resolve to strengthen movements that would put pressures on their government on decisions pertaining to conservation, restoration and integration of the natural assets are marred. Therefore, struggles for the achievement of a sustainable development rooted in the idea of build-with-nature has to be popularized through concerted campaigns. Importantly, the socio-environmental movements would also have to collectively with other democratic rights movements plan and implement or facilitate the implementation of projects that demonstrate their multiple benefits and through that process gain experience in strengthening their movements. The idea of expanding public open spaces that include the integration of natural areas as an idea of open spaces could be one objective example. This is one effective means through which people will relate to the natural assets, including water and the watercourses. Such projects would inevitably include undoing many works that have been implemented over the years, including demolition of the concrete walls built along waterbodies, watercourses and the coastline.

about the writer

Meredith Dobbie

Meredith Dobbie is a landscape architect and research fellow at Monash University. Her research interests revolve around urban nature, landscape aesthetics and sustainable landscape design.

Meredith Dobbie

Scientific literacy is recognised as essential for full participation in society and preparation for life-long learning. Without it, water users are less likely to understand the water cycle and all its consequences for sustainable, and ethical, urban water use and management. Scientific literacy should include both knowledge about science and knowledge of science. Worryingly, it is decreasing in Australia amongst school students and adults. In 2018, Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) testing showed that scientific literacy of Australian 15-year old students ranked 13th among 78 OECD countries, with six other countries at the same level (Should Australia worry about drop in PISA rankings?). Australia’s ranking has been declining since 2009. Using a survey based on one developed by the California Academy of Science, the Australian Academy of Science in 2013 reported that scientific literacy among Australian adults had also declined since an earlier test in 2010 (Science Literacy Report 2013). Most Australians had a basic grasp of key scientific concepts but, as an example of water-related knowledge, only 9% of respondents knew that 3% of the earth’s water was fresh. This percentage had declined from 12% in 2010. Generally, younger respondents, men and those with higher education were more likely to answer questions correctly. Worryingly, knowledge levels had dropped the most in young people.

Declining scientific literacy has attracted commentary about school curriculum content and how science is taught. Especially important is to engage primary school students more with science, and to ensure that those students who are interested in science can relate what they are taught in school to their own lives (Science curriculum needs to do more to engage primary school students; Science literacy is a crucial skill). The Australian Curriculum emphasizes the importance of scientific literacy in practice. This will be critical to enabling Australians to observe the code for the ethical basis for water rights and obligations in cities.

Changing behaviour is a greater challenge than ensuring scientific literacy, I think. Behaviour change can be in response to regulations or it can be voluntary. A regulatory approach might involve price increases to reduce water consumption. This approach, though, does raise issues for a code concerned with ethical water rights and obligations. Certainly, higher prices disadvantage those with lower incomes, which is hardly ethical. Voluntary behaviour change is preferable. There are many influences on voluntary behaviour change (Guide to promoting water sensitive behaviour), including awareness, skills and knowledge, costs versus benefits (e.g. financial, physical, emotional, mental), social norms and personal values, emotions, cognitive biases, and contextual factors (e.g. availability of alternative water sources). These all demand our attention if we aspire to change peoples’ behaviour in line with the draft code. However, they can be considered as nested, i.e. awareness, skills and knowledge, personal values, emotions and cognitive biases are personal attributes, which are likely to influence assessments of costs versus benefits and influence responses to social norms (although they help establish them) and contextual factors.

Scientific literacy can contribute awareness, skills and knowledge that support the code, thereby promoting behaviour change. Such knowledge can also help shape personal values. What then of emotions and cognitive biases? What can we do to manage these to facilitate behaviour change?

Cognitive biases are assumptions and (mis)perceptions that people have, which can influence behaviour or affect responses to new information. People are inclined to compare new information with what they already believe and to discard the new information if inconsistent with the old. It can be hard to convince people that new information is correct.

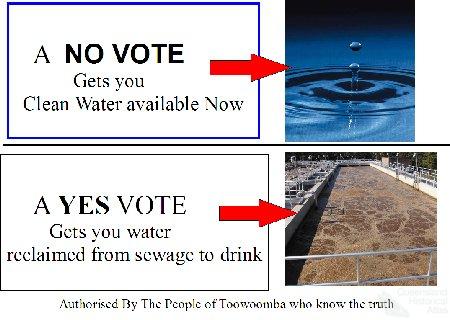

An example relevant to the water code is the Yuck factor. This is an immediate emotional response of disgust to the notion of drinking recycled water, associated with the perceived dirtiness of the water and a fear of contamination (Psychological_aspects_of_rejection_of_recycled_water). Opponents of recycled wastewater in Toowoomba used the Yuck factor in their campaign in 2006 to great effect. There is some debate whether emotional responses precede or follow cognitive responses, i.e. whether we feel before we think or think before we feel when we experience, or even consider, something and express a preference (Feeling and thinking). The idea of feeling before thinking makes sense to me. And here lies the potential for behaviour change consistent with the code, especially problematic item 5. People might initially dislike the idea of reusing treated wastewater, but with scientific literacy, thinking can override feeling, so that recycling water can become acceptable.

I believe that, with scientific literacy and programs supporting behaviour change, implementation of the code by water users is possible. I look forward to seeing how the code develops further to become a document that inspires and supports the ethical use of water for the benefit of all.

about the writer

Gary Grant

Gary Grant is a Chartered Environmentalist, Fellow of the Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management, Fellow of the Leeds Sustainability Institute, and Thesis Supervisor at the Bartlett Faculty of the Built Environment, University College London. He is Director of the Green Infrastructure Consultancy (http://greeninfrastructureconsultancy.com/).

Gary Grant

I suggest something like:

Declaration

- Human activities are responsible for the use of most of the Earth’s freshwater, which is finite

- Whilst some people have more than enough clean freshwater, many others do not

- Current patterns of consumption and management of clean freshwater have damaging effects on the natural environment and cannot be sustained, a problem that is being exacerbated by climate change

- For civilization to persist and thrive and nature to be restored, we must all change the ways that we consume and manage clean freshwater

Commitments

As a consumer of clean water, I commit to:

- Learning about the water cycle and its role in nature

- Using water carefully and mindfully

- Not wasting or polluting water

We, as water suppliers, commit to working in constructive partnership with citizens and governments to:

- Increase everyone’s knowledge of the water cycle

- Improve the measurement of water consumption and impacts on nature and sharing that information with everyone

- Invest in appropriate techniques that clean, conserve and recycle water

- Prevent pollutants and untreated wastewater from entering the environment

- Adopt pricing arrangements that ensure resilience and good stewardship whilst meeting the basic needs of all

We, as government, business and civil society at all levels, commit to:

- Governance of water supply and management which is mindful of this Code

- Swift and appropriate action in the face of the related global crises of water scarcity, climate change and biodiversity loss

- Ensuring that everyone has access to clean water for drinking and bathing and that cultural and individual diversity is respected

- Ensuring that water management is not driven primarily for financial gain

- Ensuring collection and open dissemination of information and promotion of research, innovation and good practice

- Adopting and implementing appropriate policies, strategies and plans with, and for, everyone

about the writer

Andrew Grant

Andrew formed Grant Associates in 1997 to explore the emerging frontiers of landscape architecture within sustainable development. He has a fascination with creative ecology and the promotion of quality and innovation in landscape design. Each of his projects responds to the place, its inherent ecology and its people.

Andrew Grant

—Leonardo da Vinci

If there is to be an ethical code for water in cities it must not be just human focussed. Yes, at the most basic level it is important that all humanity has equitable and appropriate access to clean and healthy freshwater to sustain our life. However, there must be a mechanism to balance our human urban water needs with those of all other life forms. In extremis could we survive as a species if we used all the available freshwater at the expense of every other flora and fauna species in the city? Imagine having a belly full of water looking out across a desert city with no trees , no animation from birds and insects, no scent from flowers and no sounds from barking dogs and howling monkeys.

It is interesting that we immediately structure our approach to urban water ethics around water specific awareness, governance, and technologies rather than placing it into a debate about our wider human life support needs for air, water, food and sensory wellbeing. How should we share freshwater across species that sustains all life in an equitable way but which ensures all of our human needs are met?

Another theme is how water shapes the identity of cities in different ways in different part of the world. My home city is Bath in the UK, named Aquae Sulis by the Romans, is a city built on and from its water. The hot springs that emerge at the heart of the city fell as rain over 10,000 years ago on the hills many miles away and continue to give life to the identity of our city and its reputation as a therapeutic refuge. The surrounding landscape is alive with natural springs and the river Avon itself has carved out the distinctive natural topography of the valleys that create the setting for this UNESCO World Heritage Site. The point is this water based identity is an identity borrowed from times past. If we have an ethical approach to water in cities should we also consider the legacy for the future and not diminish the cultural and natural heritage that we have inherited.

about the writer

Juliana Landolfi de Carvalho

Juliana Wilse Landolfi Teixeira de Carvalho is a PhD research student in Hydrogeomorphology Laboratory, Department of Geography, Federal University of Paraná. Curitiba / Brazil.Researcher on nature-based solutions for urban drainage, Urban Hydrology, hydraulic and hydrological modeling.

Juliana Wilse Landolfi Teixeira de Carvalho

Currently, about 55% of the world population lives in urban areas. UN-Habitat (2016) estimated that by 2050, the world population must reach ten billion, with around 70% of the world population living in cities. It is exceptionally alarming when merged with the UNESCO Water Report (2018), which states that by the year 2050, about 5 billion people will suffer from water scarcity at some level. Furthermore, the number of people at risk of flooding should increase from the current 1.2 billion to 1.6 billion, given that the urban population will be the most affected by these extreme weather events. These risks depend on the magnitude and rate of warming, geographic location, vulnerability, and the choices and implementation of adaptation and mitigation options.

In the urban environment context, it is essential to consider that cities are built on watersheds, and, therefore, the urban space configuration can affect the urban water cycle dynamics, changing the rates of water balance components, decreasing water security, and intensifying drought and flood risk.

Face to the urban growth, associated with climate change scenarios and water management challenges, the “code for the ethical use of water in the cities” is urgent and necessary, especially in the poorest countries, where social inequality increases, territory management, and urban planning are shallow, and population awareness has not been a priority.

The eighteen basic principles listed in the code are consistent and realistic, recognizing that the universal right to clean and safe water is not being ensured to everyone. It covers climate change scenarios, upstream and downstream impacts of urban water systems; water private control as the risk of exclusion from water access; the necessity of watershed management; collective responsibility for water use, and collaboration among different entities in society to achieve stipulated objectives.

I believe that the key point of the “Commitment for Users” item is the emphasis on understanding the water cycle systematicity, with questions such as: Where does the water that I consume in my house come from? Where does it go to? What are the impacts of my water use on the environment? How can I reduce them? What shifts about consumption patterns can I take to reduce my impact?

The “Commitment for water suppliers, government, and business” are also consistent. I suggest adding an item about “investing in research about improving urban water management (water security, universal access to water, rainwater use, wastewater treatment and reuse, decreasing impacts on ecosystems; benefits of greening cities for risk management, Nature-based Solutions for water management).

There would be many benefits if this code were applied in my city. I live in Curitiba, the capital of the State of Paraná, southern Brazil. It is a densely urbanized city, whose metropolitan complex has more than 3 million inhabitants. The city suffers from several issues related to water management: urban flooding, water scarcity, water pollution, denaturalization of rivers and hydrological processes.

Currently, we suffer the most severe drought recorded in the last 100 years. With rainfall below the historical average, the level of our reservoirs reached less than 30%. The drought’s result is a severe rotation of water supply, which, unfortunately, disadvantages the poorer classes. In the pandemic context, where there is a recommendation to wash hands several times a day, thousands of citizens often suffer from water scarcity.

I understand that the application of this Code for the Ethical Use of Water in Cities could set up a different scenario from that we currently experience on water management during this drought period in my region. We could also have different scenarios related to urban floods that are recurrent every year, causing numerous demages to the population and the and public management.

References

IPCC, 2018: Summary for Policymakers. In: Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, H. O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J. B. R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M. I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, T. Waterfield (eds.)]. In Press.

UNESCO. 2018. The United Nations World Water Development Report 2018: Nature-based Solutions for Water. Paris, UNESCO.

Un-Habitat. 2016. World Cities Report 2016: Urbanization and development, emerging futures. United Nations Human Settlements Programme. https://www.unhabitat.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/WCR-%20Full-Report-2016.pdf

about the writer

Tom Liptan

Tom Liptan is a registered landscape architect and a retired environmental specialist for the City of Portland Bureau of Environmental Services. Liptan has assisted numerous municipalities, developers, consultants, multi-state corporations and government agencies with acceptance of ecoroofs and other landscape approaches used for stormwater management and healthy city development. His leadership on ecoroofs and green streets has also had an international impact. He has lectured and published widely, and is the author of the 2017 book Sustainable Stormwater Management.

Tom Liptan

So the first commitment is a good starting point: “1. Understanding my local and global water cycles.” I am a retired water management professional, what do I really know. Here are some randomly related thoughts.

My water purveyor is the city of Portland. From 1850-1895 the city used water from the local river until it became obvious that it was being uncontrolably polluted. This water source was unsustainable based on the known technologies to filter water at the time. So in 1895 the city purchased land in the nearby mountains, not the large snow covered Mt Hood, but the rain drenched watershed of Bull Run. Two dams were built which created two reservoirs and all water could be transported to Portland via gravity and a small amount of electricity is produced in the process. However, the west side of town is up hill so the entire westside must have water pumped up hill from the eastside.

This is just the tip of the Portland water story—A 100 year struggle ensued to protect the forest from logging, it was recently successfully concluded with the US Forest Service. Sometime in 1960-70s the city decided to back up its almost pristine supply with another source, groundwater. This was smart but unbeknownst to the city would be fraught with challenges. For example several years after developing the wells the city planners designated the zoning for industrial uses. The water bureau freaked out and groundwater pollution prevention codes were hastily adopted vs. changing the zoning. In the 1980-2000 a project was required by state law to remove 50,000 cesspools and replace them with a conventional sanitary pipe system at a cost to property owners of $10,000-20,000 each property. This was required to eliminate the risk to groundwater and the bureau required to implement the requirements was BES. Interestingly, in a recent conversation with a water bureau employee, he had no knowledge that this project ever happened. Once something like that is done and 20 years go by I guess it’s easily forgotten.

More recently, the state required BES to determine if its use of sumps for stormwater management might pose a risk to ground water. The person at WB didn’t know about this either. He was a little concerned when I shared what I know of the results. There are 10,000 sumps in the area of concern above the aquifer. Based on what they found the sumps won’t be removed.

It points out to me that understanding my local water cycle related to my drinking water system is quite complex, let alone the global cycles, so as a commitment I think local is of primary concern. Also understanding how our actions might or do affect other people’s water would be a part of local to local relationships. Isn’t it so strange, water is life, but most of us know so little.

Something about else about water, which I didn’t see in the code: Water is an elusive reality, both good and absolutely essential, yet how astounding that it can/does take on such huge physical dimensions and energy to cause death and destruction. From a tiny drop to an enormous tsunami.

One thing for sure, at least for me, is that the code is very thought provoking. I very much appreciate your invitation.

about the writer

Harini Nagendra

Harini Nagendra is a Professor of Sustainability at Azim Premji University, Bangalore, India. She uses social and ecological approaches to examine the factors shaping the sustainability of forests and cities in the south Asian context. Her books include “Cities and Canopies: Trees of Indian Cities” and "Shades of Blue: Connecting the Drops in India's Cities" (Penguin India, 2023) (with Seema Mundoli), and “The Bangalore Detectives Club” historical mystery series set in 1920s colonial India.

Harini Nagendra

Could I think of using this Code in practice to transform my city? I speak of the city of Bangalore, one of India’s largest and fastest growing cities, fueled by the IT boom, and running out of water. Located in a semi-dry environment, without access to a large river or any perennial sources of fresh water, Bangalore depends on a range of unreliable sources for its water supply, including water on tap from the drying, distant Cauvery river, depleting ground water mined from local borewells and supplied in tankers, and open wells and tanks fed by a mix of rainwater, sewage and industrial effluents. Summer headlines regularly warn that Bangalore is about to become the next Cape Town, running out of water soon—yet somehow the city lurches past another almost-drought year, and towards the next, without very much changing on the ground.

If we could get the various actors that are part of driving water use in Bangalore—the municipality, Government sewage and water supply board, water tanker groups, industries and companies that use large quantities of water, academics, civil society, and other relevant groups—to sign on to a water manifesto, this would be an excellent one. The basic tenets—of equity, sustainability, respecting limits to growth, vulnerability and resilience—are all in place. Yet there are a number of challenges with creating an ethical code that works in practice. First of course, in contexts such as Indian cities, where different groups access water, from diverse religious, cultural and economic backgrounds, values can bring people together to forge a common shared understanding—but a clash in values can also engender conflict. Water wars have taken place within countries and communities as well across different borders and diverse groups. The ethical water code, while identifying important sources of conflict such as the clash of interests between supply-driven business and the demands of reducing frivolous consumption, does not speak of differences in cultural and religious perspectives. Indeed it would be difficult to do so in a code that intends to work across contexts: such a code would need to be easy to accept both in societies where norms of water use are strongly driven by religion and culture, as well as societies where norms are driven by considerations of capital, and a host of other contexts. Yet in making the considerations of ethics broad enough to be accepted by all, there lies a challenge for places where customary laws are largely in force, but being challenged by new values emerging with “modernity”.

Ultimately, while codes lay out a desired goal and endpoint, they cannot in themselves specify the process by which we intend to reach such goals. Ideally, an ethical water code could help outline some useful signposts that can guide us towards the right path or set of possible paths. One such signpost, identified by many scholars and practitioners, is the need for polycentricity, or the presence of multiple levels and levers of governance. The ethical water code recognizes such a need. It identifies the need for multi-stakeholder engagement, specifically pointing to governments at multiple levels, civil society, academia, industry, communities, and individuals. A second signpost or metric is that of justice: the ethical code keeps this recognition at its core, fundamentally asking for people and nature to receive their due rights to water.

A third signpost, more difficult to accommodate in an all-encompassing water code, is the need to make place for diverse water imaginations. Across the Indian state of Karnataka, rural and peri-urban communities get together to sing songs to the God of the monsoon, Maleraya, asking him to pour down on them—not alone, but with his family in tow. Maleraya, in turn, will not respond until the 7 rulers of 7 villages get together, cook a communal meal, sit together for a bit, stand together for a while, and then ask him to rain down—he does not respond to individual requests, only collective ones. He does not respond as an individual, but as a member of a community, a family of rain gods in the sky. As the city urbanizes, and the songs of Maleraya fade from our collective memory, we lose a core ethic—of water as a community resource, governed by a communitarian ethic.

Ethics and norms grow in the well fertilized water of imagination and culture. Keeping space for a diversity of imaginations to flourish in close proximity will be essential if we are to make the water code work in practice. The challenge will be to do this in a way that works across locations, cultures and imaginations.

about the writer

Naomi Tsur

Naomi Tsur is Founder and Chair of the Israel Urban Forum, Chair of the Jerusalem Green Fund, Founder and Head of Green Pilgrim Jerusalem, and served a term as Deputy Mayor of Jerusalem, responsible for planning and the environment.

Naomi Tsur

Water is the second most essential need for living creatures. Without air, we can survive for only a few minutes. Without water, we may last one or two days. Without food, the third essential, we can survive for much longer. I am not sure that we give water the respect it deserves, nor do we pay enough attention to the suffering caused in many parts of the world either by a lack or an excess of water. That is why I was more than pleased to be a member of the team that got together after the workshop on water-scarce cities that was held at the TNOC Summit in June 2020 in Paris. We all felt that the importance of water is such that there is a need to examine it from an ethical viewpoint. This feeling was strengthened for me by my own urban experience in Israel.

My city, Jerusalem, has been at the center of conflict from the time it was wrested from the Jebusite tribe by King David, some three thousand years ago. Situated high in the Judean Hills, from the very first the major challenge was to gain access to a reliable water supply. It was only in the reign of King Hezekiah that a channel was carved, granting access to the Siloam Spring from within the walls of the city. On the west side of Jerusalem, well beyond the city walls, natural springs provided water for the terraced agriculture of the Jerusalem hills. The terraces enabled retention of water, and in turn the sustenance of crops suited to the hilly terrain.

Until the middle of the nineteenth century, the whole city was contained within the famous walls built by Suleiman the Magnificent four hundred years earlier. One feature of Ottoman Jerusalem was the beautifully sculpted water fountains placed in different sections of the city, providing free clean water for residents and visitors alike.

Water has always been part of the story of Jerusalem, in an arid part of the world, with no rain for seven months of the year. When the city began to expand beyond Suleiman’s walls, no building, public or private, was built without adequate rainwater cisterns. These cisterns were what enabled the residents of Jerusalem to get through the siege in 1948, just as their ancestors had survived seven months of siege by the Romans two thousand years before.

Modern day Jerusalem is home to some 900,000 residents, and can no longer rely on cisterns and springs for all its needs. A new major water pipe carries desalinated water from the Mediterranean to the city. At least three quarters of Jerusalem’s sewage receives advanced treatment and is used for agriculture, as well as providing water for the city’s public parks and gardens.

An important challenge for Jerusalem is finding beneficial ways to use run-off from the rainy season. The steep hilly topography results in most of Jerusalem’s precipitation running down to the Mediterranean on the west side, and to the Dead Sea on the east side of the city. We are told that the amount of rainfall in the five wet months is the equivalent of about three quarters of the city’s total water needs. However, not only is it largely wasted, but it is also a major pollutant of groundwater, since it collects dirt and refuse before flowing down to the aquifer. In one major city initiative, the Gazelle Valley Park, a series of natural pools filters and cleans about one quarter of Jerusalem’s rainfall. We are used to the concept of a “green lung”, but this nature park has resulted in a new urban anatomical term, “a green kidney”.

In collaboration with the Jerusalem Municipality, a special team of municipal experts and civil society has been established, the Jerusalem Water Forum, which is a water policy think tank for the city. It is proving to be a very useful arena for sharing ideas, and for promoting better water management in the city.

It is often said that major conflicts of the future will be about water. The challenge for all of us is surely to make water a force for better and more ethical human behavior.

about the writer

Diane Pataki

Diane Pataki is a Professor of Biological Sciences, an Adjunct Professor of City & Metropolitan Planning, and Associate Vice President for Research at the University of Utah. She studies the role of urban landscaping and forestry in the socioecology of cities.]

Diane Pataki

I started my career studying the water needs of natural and plantation forests in the eastern part of the U.S., where rainfall is relatively abundant. When I moved to the western deserts, I worried that that the water requirements of urban trees and gardens were on track to outstrip the dwindling water supply of cities like Las Vegas, Los Angeles, and Salt Lake City. I started a research lab to study the water demand of urban trees and landscapes, hoping to find solutions to problem of greening cities in the face of severe water shortages.

Over the years I’ve found that with one glaring exceptions (lawns), many cherished urban landscape trees and other plants require much less water than expected. Unfortunately, many American homeowners greatly over-water their landscapes. The history of water, land use, and governance in the United States has led to perverse incentives to over-irrigate, even in the face of drought. Water is often cheap, especially for the wealthy, leading to growing inequities and injustices in the costs and benefits of accessing and using water.

The American West, and many other regions around the world, continue to get hotter, drier, and more unsustainable. But our use of water, and more importantly our relationship with water, is not changing very quickly, if at all. Over irrigation is still everywhere, and most American cities still fail to capture and recycle sustainable sources of water. Yet as I write my city is filled with smoke from massive wildfires of unprecedented magnitude. It has never been more apparent that people, landscapes, and water are all interrelated, and we will suffer or succeed together.

It’s been a privilege to talk with Naomi, Peter, Paul, and Mario about the ethical dimensions of the predicament in which we now find ourselves. What is the right thing to do with respect to water and all of the living systems on earth that depend on it? I hope you will find this dialogue intriguing, and I look forward to hearing many more voices and perspectives about our ethical obligations toward water, the land, and each other.

about the writer

Peter Schoonmaker

Peter Schoonmaker leads the outdoor education program at American Community School Beirut, and is president of Illahee, a non-profit organization focused on designing new models for cooperative environmental/social/economic problem solving.

Peter Schoonmaker

Tell me, did water figure prominently or specifically in your memories? Did water quantity, quality, availability, cost —or any other attributes—come to mind?

Me neither. Even though I spent part of my childhood in water-scarce southern California, and late teens / early twenties building an irrigation system. Lived in a temperate rainforest. And later spent a few years in one of the driest deserts in the world, where acquiring and rationing water was a daily activity. Where you packed 40 to 50 pounds of water (you measure it in pounds when it’s on your back) into remote study sites.

Maybe it’s different if your survival—your business, your farm, your family budget—is acutely (like, life and death) affected by water. Even then, it’s likely many of us think of things other than water when we think of home.

Now I think about water all the time, wherever I go, but that’s a professional hazard as an ecologist interested in policy and civic design. Travelling from Portland, Oregon’s abundant water sources and ample distribution system to Dubai’s obligate desalinated / bottled water system is a shock. Then there are the ground-water dependent systems scattered throughout most rural areas in the western United States and indeed the world.

The point is, most of us take water for granted. Other people provide it, for a price, and water drains away after we’re done with it. Water rises to our attention only when there’s too little or too much. And then, when our need is addressed, it’s on to other things.

The case for an “ethical code for water” would be hard to make if water were universally unlimited, like air (before pollution) or starry nights (before cities). It’s the limitation, or excess, that demands an ethic. Five of us have hammered out a draft of an ethical code for water. Five people with various water experiences and memories. Perhaps some of my colleagues have known water deprivation as both a daily and life-long existential threat. I never have. My experience is limited. The five of us—our experience is limited.

We need to comb through this document with more experience; to hear from people who have known acute water deprivation and oversupply, high costs and “too cheap to meter,” water as a daily focus and an after-thought, water at the center of their lived memory and water as a policy object. A water ethics that works for billions of people and the ecosystems they inhabit has to start somewhere. Maybe it starts with our memories of water. Take another thirty seconds.

about the writer

Mario Yanez

Mario Yanez is dedicated to envisioning and inspiring a transition toward life-sustaining, regenerative human communities. As a whole-systems designer, he is working globally at various scales, implementing productive landscapes and ecosocial systems. As a scholar-practitioner, he is researching complexity and pathways toward cultivating wholeness in society and economy.

Mario Yanez

My terrain at moment is Lisbon. A beautiful, mostly ancient City. I recently learned that many smaller rivers snake their way through the city’s undulating hills eventually finding their path to the Tagus river, as it too makes its way toward the Atlantic Ocean. You can’t see these rivers anymore, but I’m told they still flow under the streets. When I take long walks down towards the Tagus I imagine them flowing under me.

It’s too easy take for granted that I can turn on my tap and water streams out. On one of my walks a few days ago, a friend pointed out some remnants of the old Roman aqueduct that used to run through the city. It’s amazing how much effort and energy is spent creating infrastructure—artificial rivers—in our cities to bring freshwater in and deal with or dispose of “waste” water. It’s clear we are not doing all this so gracefully—measured by the degree we expend energy and apply technology to replace services freely given by ecosystems.

As one steeped in ecology, I know intuitively that at the right scale it is possible to participate regeneratively, to repair our water cycles and reverse desertification. But, what is the right scale? Many of our cities started as small settlements strategically placed along rivers or other bodies of water. They have rapidly outgrown the ability to participate gracefully within their watersheds—taking too much water out of circulation, transforming it in ways that make it useable again. Cities, by definition, tend to overrun the local ecosystems that once sustained them—then they go global.

These thoughts are very present with me as some friends and I are working towards establishing an intentional community 40 minutes north of Lisbon. I am leading the overall design of the 46-hectare site. It is beautiful land, a pleasant topography of clay-laden soils with several patches of healthy forest on it. There are no rivers on it, a few naturally-occurring springs, although when it rains a fair amount of water runs through it. I think a lot about the effort we’ll go through to regenerate the productive capacity of the site, to prepare the site for 100 or so families who will participate in the water cycle there. I try to imagine us harvesting, storing, using and reintegrating water as part of living there, growing food and satisfying other material needs.

Water is life. One could say water is food is life. This notion becomes obvious to me sometimes as I work out how to keep produce alive when I bring it home from the market. I try to find the right balance of internal moisture. I bag the carrots so they remain crisp, set the bouquet of parsley in a glass of water with a bag over it, cut up and freeze peppers, and keep onions and tubers dry and well ventilated. Too much water and things rot. Too little water and they dry out. This is true for cells, organisms, cities, and bioregions.

All this to say that I instinctively came to the session on water scarcity and recognized that I wasn’t alone in wanting to create a world of freshwater abundance—in other words, a living world. For me, this ethical code we have drafted is a plea for life. For my own rivers inside and those that run beneath my feet. For those that run freely further afield, and for the ones that move through the air and rain down elsewhere that eventually make their way back to me.

about the writer

Paul Currie

Paul Currie is a Director of the Urban Systems Unit at ICLEI Africa. He is a researcher of African urban resource and service systems, with interest in connecting quantitative analysis with storytelling and visual elicitation.

Paul Currie

When asking this to groups of students or workshop participants, the answers have been some of the most poignant. Everyone and everything on the plant touches water. It is the substance that connects us all, and illuminates easily our different histories, geographies and life experiences. These memories of first baths, puddle jumping in the rain, drinking from a plastic bottle, being cleaned with a cloth, noticing water’s taste for the first time, floating on lakes, splashing in rivers, or seeking hidden resources, show how water is tied to our emotions and relationships.

In this way, resources of water, food, energy, materials are entwined with who we are and how we engage the world. They are not simply enablers, technical infrastructures or disconnected flows, but have strong socio-political resonance. I use these resource flows as a lens for urban sustainability, with particular attention paid to equity of access and quality of the resource.

When joining The Nature of Cities Summit session on Greening Water Stressed Cities, we were one year past the worst drought Cape Town had experienced. I was intrigued that the water crisis was as much a political crisis as it was a technical one. I was intrigued to see climate change as a tangible, present experience, not the ever-approaching but distant concern. I was amazed by how radically water use could be reduced (halved in 18 months), and reminded again of the disjuncture between universal messaging and differential realities: should we really be asking those in informal settlements to reduce their already-low use of water? Given our different experiences of water, should there be one universal ethic for our relationship with water. Given a simplistic distinction between cities that flood and cities that experience drought (or even cities that experience both in a year), is is possible to provide one guidance to both situations at once?

I did not expect that the TNOC session would yield not a pragmatic technical or policy output, but instead lead to a series of deep conversations on the ethics posed by different realities of, and interactions with, water. In our conversations, we arrived at a notion of an ethical code for interacting with water. We explored how we might propose a set of responsibilities that many people and entities could relate to, and contextualise to their own cities and experiences. We organised these principles by those responsible for using, directing and regulating water. We know we have just scratched the surface, and continuously revisited the tension between a concise list and detailed explanation.

The journey to produce this ethical code has been fascinating and reflective, and I am looking forward to the next stages, as more people add their comments, critique and ideas.

about the writer

Sareh Moosavi

Sareh is a post-doctoral research fellow in landscape architecture at the Univeristé Libre de Bruxelles, Belgium. Her research interest focuses on the nexus of Design Experimentation, Nature-based Solutions for urban water management and Climate Change.

Sareh Moosavi and André Stephan

Making Invisible Water Visible

One in four large cities face water stress, and water demand is projected to increase by 55% by 2050. Furthermore, projected impacts of climate change in water-scarce regions will mean prolonged droughts, and more frequent extreme rainfall events causing flash flooding. Having a code to reduce water use and regenerate water systems is therefore direly needed and welcomed. The systemic approach of the code and its attempt at covering the entire water system is testimony to the whole-of-economy approach required to tackle water issues in cities.

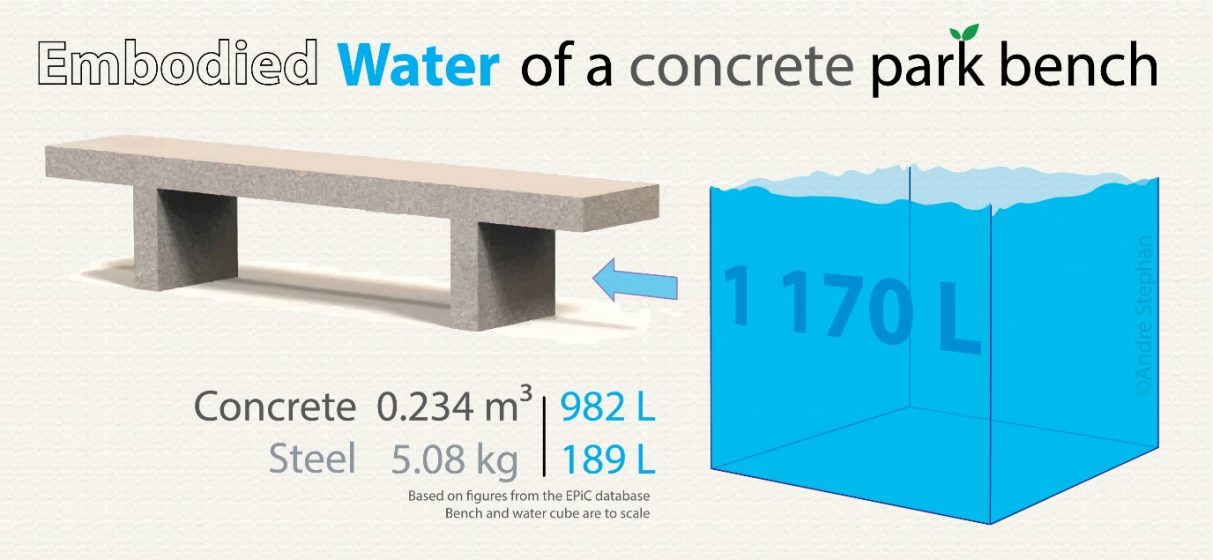

In our view, the code can further highlight the criticality of Invisible Water and the role of built environment professionals in tackling it. Water can be invisible in urban settings when it flows underground or when it only leaves marks in the landscape where it gushes during floods and rushes to the sea. Water is also needed to produce all goods, including food as well as construction materials. This embodied water is invisible to the urban consumer, or built environment professionals selecting construction materials, yet it has severe repercussions on draining water resources across supply chains, including in water-scarce regions elsewhere. We provide some thoughts about how built environment professionals can account for Invisible Water and we highlight implications to the code.

Invisible Water in Landscapes

Invisible Water in the city needs to be taken into account in any attempt to move towards more water sensitive cities. Integrated Urban Water Management (IUWM) considers a whole‑of-catchment approach in co-ordinating the management of land, water and other natural resources. IUWM aims to help cities progress towards a more circular economy, by closing the water loop, helping limit the discharge of (liquid) waste in waterways, and limiting the constantly growing need for additional water resources. Built environment professionals such as urban planners, architects, landscape architects, urbanists and construction engineers, play an important role in sustainable distribution, use, discharge, and reuse of water in our cities. They need to consider Invisible Water when making decisions on where to place new developments or implement Nature-based Solutions in urban areas. By considering the underlying ecological and hydrological systems (i.e. Invisible Water), decisions can be made to make the best use out of stormwater runoff and to optimize the required hard infrastructure (e.g. drainage pipes). This means understanding how water moves in and around the site depending on the topography, and accordingly restoring and creating green networks in the footprint of moist soil.

In the Middle East, for example, a number of design firms have refuted the idea of copying western-style green spaces often with vast areas of lawn requiring large amounts of water, and have taken on the challenge to experiment with new forms of linear urban parks in the abandoned dry water channels, often known as wadis. This requires innovative approaches in designing adaptive and flexible landscapes that can accommodate flooding in extreme rainfall events while serving as public parks in dry seasons. The Invisible Water flowing in shallow aquifers along these corridors can often support revegetation of the channel, and strategically planted “oases” with native plants can store water underground, but also bring water back to the surface on the long-term, a technique that was traditionally used by native desert inhabitants.

Embodied Water in the built environment

Invisible Water embodied in goods, products and services, including construction materials and activities, is similarly critical to address. Built environment professionals, across all disciplines, need to better understand the embodied water associated with their design choices, notably as embodied Invisible Water represents the largest part of the water use of a city, house and even transport modes. This can only be made possible by making relevant data fully accessible, transparent and consistent so that higher education institutions and practices can capitalize on this new knowledge and use it for training and design purposes, respectively. As such, the Australian Environmental Performance in Construction (EPiC) database of embodied environmental flows should be highlighted. Being available in open-access, as advocated for by the code (items 3 and 6), it has been adopted by multiple built environment associations and practices and is raising awareness about embodied water on the driest inhabited continent on Earth. Similar initiatives are needed in data-poor regions, which often happen to suffer also from water-scarcity, in order to relieve pressure on far-away aquifers. The Mediterranean region for example, will be significantly drier in the coming decades, potentially seeing 40 percent less precipitation during the winter rainy season. Yet, most countries in the South of the Mediterranean have access to very limited data to inform their designs in regard to Invisible Water.

We propose adding the following commitments for built environment professionals:

- Understanding the importance of Invisible Water, including underlying hydrological systems, but also embodied water flows for construction of materials and infrastructure assets

- Taking account of water requirements of plants and materials used in designs

- Learning from the past and traditional approaches of first nations peoples in sustainable water management

about the writer

André Stephan

André is a Professor of Environmental Performance and Parametric design at the Université Catholique de Louvain, Belgium. He develops advanced models to quantify and better understand life cycle environmental performance in the built environment.

about the writer

Katherine Berthon

Katherine is a PhD candidate at the Interdisciplinary Conservation Science Group at RMIT university. Her passion for conservation biology and curiosity for understanding natural phenomena has led to a diverse research background in animal behaviour, spatial analysis, invasion biology and ecological theory.

Katherine Berthon and Casey Furlong

The code provides a good summary of the challenges and divided responsibility in managing water at different scales, but there are some improvements to be made with respect to understanding the broader context and application of the code, as well as clarity in wording of certain points.

For cities that already have high standards of water management, such as Melbourne, the code is not transformational, but may allow for confirmation and fine tuning of policies by highlighting strengths and weaknesses of current approaches to water management. In this way, the code could be used as a kind of checklist, particularly for cities where water management policies are new or under development. Since many of the points are very general, it might be useful to have the code in tandem with case study examples to guide cities that do not already have appropriate policies or governance structures.

It would also be useful to articulate if, and how, the code intends to work within the broader governance context for water management outside of urban jurisdictions. Missing from the code, e.g. point 3.1, is an important concept of environmental water. Environmental Water Requirements (EWR) are the volume of water that is reserved for ensuring the ongoing functioning of freshwater ecosystems (Smakhtin, 2004 p v). Water use without appropriate regard to EWR can lead to over extraction, dry riverbeds and poor environmental outcomes (Vertessey et al. 2019, p 8-9). We recommend inclusion of a clause explicitly addressing the need for governance systems to ensure EWR are met.

While top-down management has an important role, it also has limitations, especially in countries with high levels of government corruption, or low levels of technical and governance capacity. Point 3.1 and/or 3.8 could be explicit about including a requirement for community consultation and/or other forms of democratic process around water allocation and environmental outcomes. Similarly, point 2.5 and 3.8 could be more explicit about regulation of excessive or irresponsible use, including penalties for water users (particularly industries) that pollute, damage or disrupt supply to other water users.

*Point numbers refer to the code section (1 = water user, 2 = water supplier, 3 = water governance), followed by the subpoint for that section (as listed in the code document)

References

Radcliffe, J. C., & Page, D. (2020). Water reuse and recycling in Australia-history, current situation and future perspectives. Water Cycle, 1, 19-40.

Smakhtin, V. (2004). Taking into account environmental water requirements in global-scale water resources assessments (Vol. 2) p. v

Vertessy et al. (2019) Independent assessment of the 2018-19 fish deaths in the lower Darling: Final Report. Accessed 30/10/2020. URL: https://www.mdba.gov.au/sites/default/files/pubs/Final-Report-Independent-Panel-fish-deaths-lower%20Darling_4.pdf

about the writer

Casey Furlong

Dr Casey Furlong is a Senior Water Strategy Consultant at GHD, Senior Industry Fellow at RMIT, and Advisory Board Member at the WETT Research Centre. Since joining the water sector in 2011 Casey has worked in 5 teams at Melbourne Water, completed industry funded PhD and Post-docs, and has published a wide variety of content on water security, alternative water sources and Integrated Water Management.

Please plan to join us to further the conversation and grow into new cities, new regions at TNOC Festival 2022, March 29, 10:00 am EDT. https://t.co/PGWEE4EUMW. Please watch https://t.co/V5Z3pj8NmZ for an introduction to the Code.

A “Code for Water” is increasingly essential for survival of life on this planet.

This is a tremendous vision that will require more than planning, and ultimately enforcement.

Imho, this is a critical factor to be addressed, and a discussion that cannot be overlooked.