When is the best time to consider developing an urban ecological network plan for your city? The answer varies based on a city’s long-term planning process and the immediate issues a community may be facing, but it is always the right time to integrate ecology and nature into urban planning and revitalization efforts.

There is a growing clamor for a shift in perspectives and practices that will lead to a more resilient future. Much of this is coming from and focused on our cities, where over half of the world’s population already lives, and more are expected to join. A lens of landscape ecology and a foundation in community input provide the keys to designing for tomorrow’s resilient cities.

As an ecological planner and writer, I have found that when we pause for a moment and listen for the stories of a place, we become more aware of its essence. We notice the patterns and processes that root us in a sense of belonging, a call toward stewardship, and a connection to community. Many of us, without even thinking, can easily name the natural features that define our relationship to our home cities—a creek or harbor we love, a favorite woodland park, a majestic tree we could draw from memory. In some traditions, this connection of community to ecosystem is even more explicit. For example, when formally introducing themselves, the Māori people of Aotearoa (New Zealand) invoke their connection to their cultural and ecological heritage by naming the boat that brought them to the country, their mountain, their river, their marae (cultural hub/ancestral home), and their tribe. This not only grounds these individuals in the heritage of their families but also their kinship to nature and their responsibility as guardians of these landscapes. The Māori, like many indigenous peoples around the globe, value and pass down ancestral knowledge of the relationships, patterns, and rhythms of nature—a knowledge they refer to as mātauranga.

Our urban communities, likewise, have a reciprocal relationship with nature. If we steward our natural resources, restoring ecological function, and preserving the remnants of once-dominant ecosystems, everyone benefits. Access to nature has been proven time and time again to increase life expectancy, decrease recovery times from major surgeries, increase test scores, improve concentration, increase health metrics, and lead to greater happiness (sources). Unfortunately, access to green space is inequitably distributed in many of today’s cities and the integration of open and natural spaces into underserved communities often leads to gentrification and ultimately, displacement of those most vulnerable.

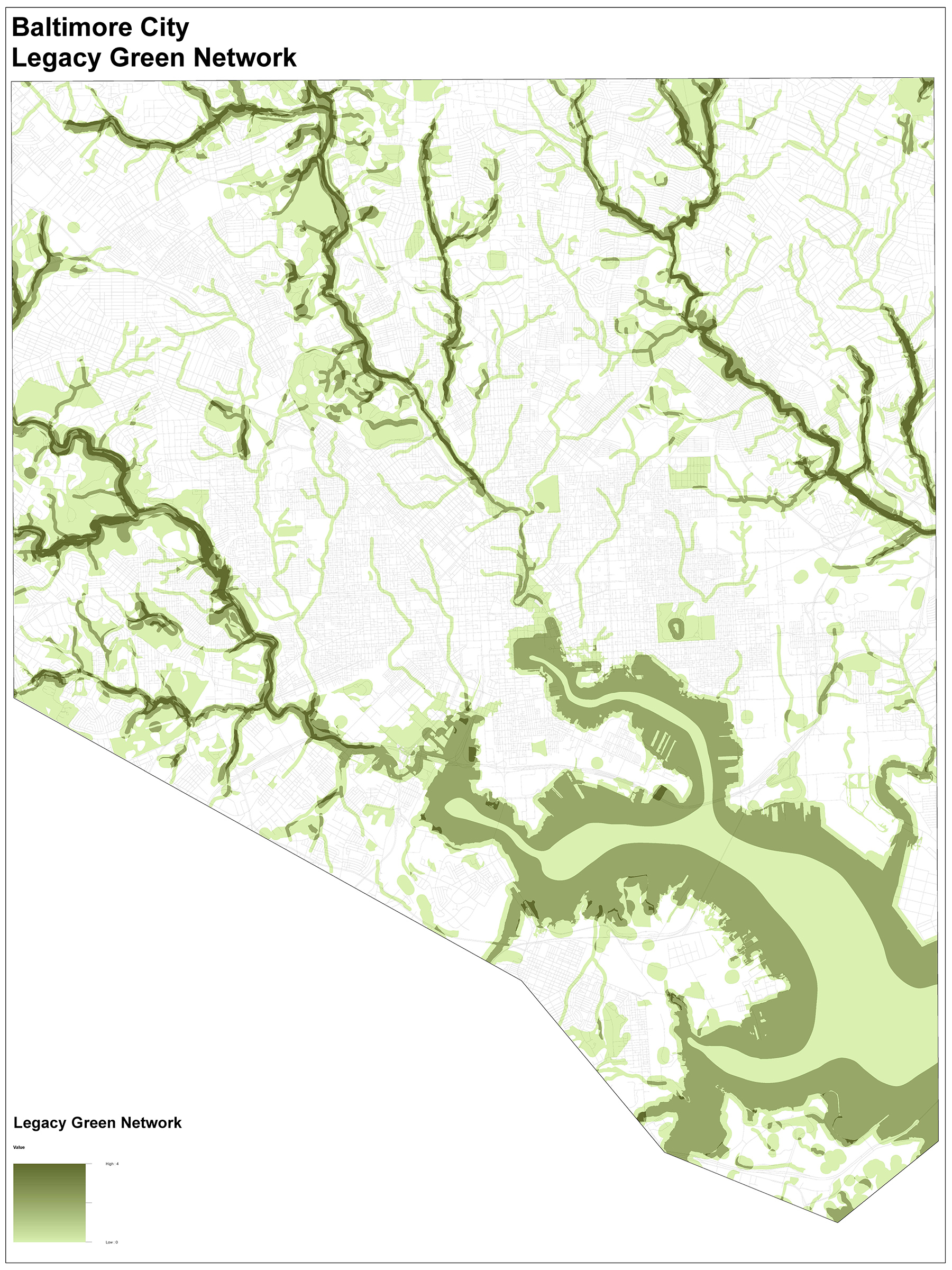

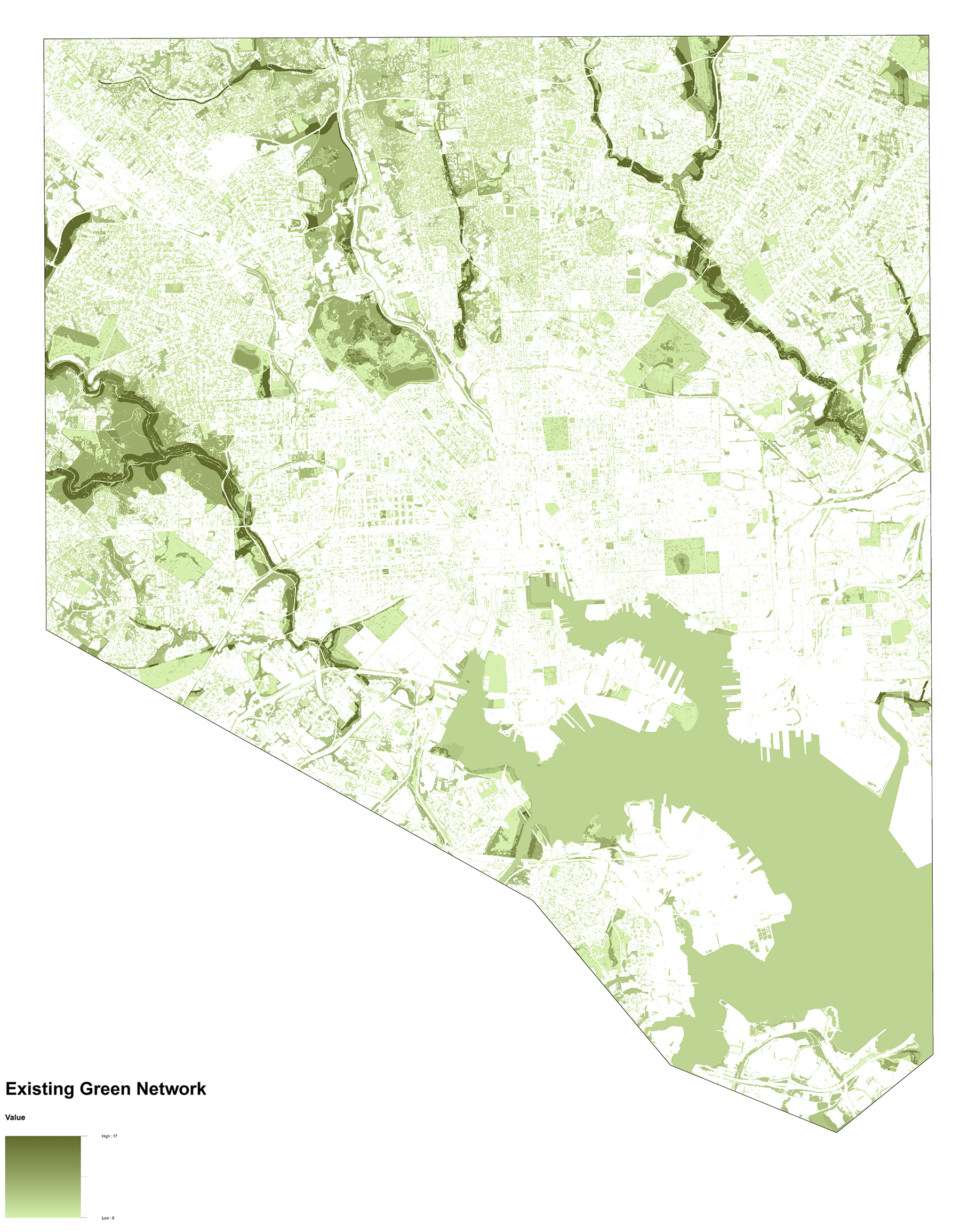

As a practice, we at Biohabitats have been applying ecological principles as an underpinning for more resilient city planning efforts through the development of urban ecological frameworks, or green network plans. We start our planning process by examining the historical ecological narrative of our cities: the geology; the rivers, streams, and creeks (some of which might have been buried or drained in the past); the wetlands and meadows that may have existed prior to our settlement; the remnant forest patches; the mountains or valleys that shape our views and access into and out of the city; and the biodiversity inherent in these systems. Much of this has settled into our consciousness as background noise to the skyscrapers, urban parks, interstate highways, bustling town centers, and neighborhoods that have come to define our identity as city dwellers. But we can bring it back to the fore as a place to begin dialogue with the community in planning for a more resilient future.

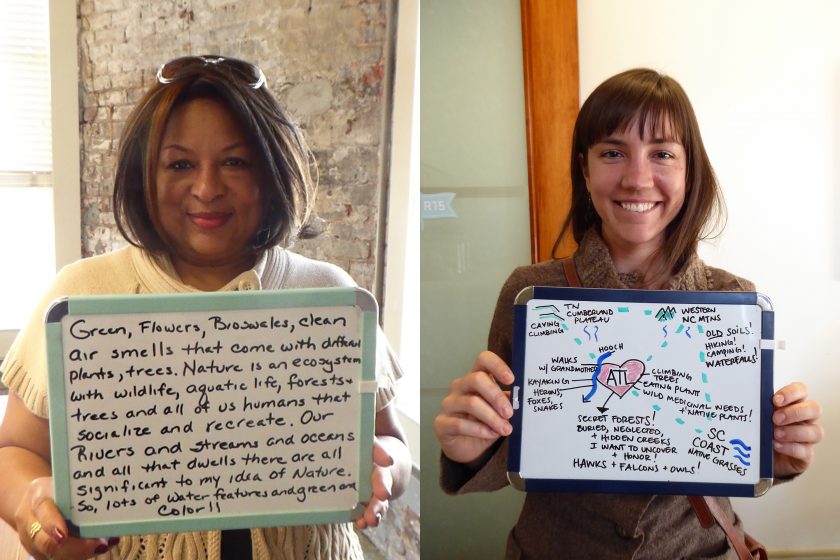

In a recent project with the Department of City Planning in Atlanta, GA, we posed the question to the community members, “What does Nature in the City mean to you?” We wanted to make sure as we kicked off an effort to help the City craft an urban ecological framework to guide future development, that we began with what the residents knew, valued, remembered, and desired of nature in their city. We were regaled with so many personal stories: tales of fishing in neighborhood creeks, tending to grandmothers’ gardens, camping under trees in backyards, hiking along stream valleys, and hearing frogs singing in wetlands and birds calling overhead. Clearly, we have not completely lost our connection to nature in our cities. On the contrary, we know, love, and seek that connection. Yet ecology has never been at the forefront of urban planning, or zoning for that matter. Now is the time to change that.

In a recent project with the Department of City Planning in Atlanta, GA, we posed the question to the community members, “What does Nature in the City mean to you?” We wanted to make sure as we kicked off an effort to help the City craft an urban ecological framework to guide future development, that we began with what the residents knew, valued, remembered, and desired of nature in their city. We were regaled with so many personal stories: tales of fishing in neighborhood creeks, tending to grandmothers’ gardens, camping under trees in backyards, hiking along stream valleys, and hearing frogs singing in wetlands and birds calling overhead. Clearly, we have not completely lost our connection to nature in our cities. On the contrary, we know, love, and seek that connection. Yet ecology has never been at the forefront of urban planning, or zoning for that matter. Now is the time to change that.

In addition to the positive public health impacts of increasing our contact with nature in cities, ecosystems provide a model for landscape resilience in response to climate change. Wetlands and marshes help to alleviate the impacts of flooding as natural sponges in the landscape. Shifting and rising dunes of barrier islands provide resilience in light of rising sea levels. Vegetated or forested floodplains provide space during massive rains to capture and contain water. Continuous tree canopy shades and cools our cities as warming continues. Wooded corridors along our rivers and streams help soak up and distribute water during large storms. In the same way that 3.8 billion years of evolution informs biomimetic design approaches, the natural systems that exist in and flow through our cities can inspire an eco-mimetic approach to urban planning.

This approach is grounded in community input and the culture that animates our cities, at the neighborhood and district scale. Add to that, input from ecologists, landscape architects, environmental engineers, city planners and staff, community leaders, economists, architects, and activists. This is an iterative and consultative interdisciplinary process. We, as ecological planners, serve to facilitate wide-ranging and inclusive discussions with residents, addressing the needs of their neighborhoods as well as those of the broader city and region. Ecosystems are not constrained by political boundaries and we are always aware that our actions have ripple effects.

Ecological framework planning weaves community input at regular intervals into a science-based design and planning approach. This is inspired by Ian McHarg’s work on Designing with Nature, which emphasizes the interactions and interrelationships between ecosystems, historical settlement patterns, and projected development. It requires an intimate understanding of the social and cultural factors at play, the basic ecosystem types and functions in question, the impact of the legacy of disempowerment and systemic racism on the community, the specific issues of climate change impacting the landscape, and the existing or projected biodiversity loss.

The general process we follow for developing an urban ecological framework includes these steps:

- Engage the community to set a vision and goals

- Analyze existing conditions to establish a narrative of place based on both ecological-social characteristics

- Conduct a needs assessment or suitability analysis with community input

- Explore alternative scenarios of change and solicit feedback on the needs and priorities in the community

- Develop a final urban ecological framework

- Create pilot projects and funding plans

- Revisit zoning and other regulatory tools for updates that reflect urban ecological guidance

While in Atlanta, our focus was on responding to population growth and its impacts on tree canopy and community access to open space, in a Green Network Plan we developed recently with the Baltimore City Planning Department. Our planning team was tasked with addressing dense areas of vacancy through this approach. In both cases, community members described how they experienced nature; which aspects of nature they wanted to see preserved, protected, and celebrated; how nature was unique or special to their daily lives; and where they thought nature made the most sense in their city- their narrative of place. There were important points raised during this dialogue about the need to support the communities in managing and maintaining restored green space and the need for affordable housing and job creation.

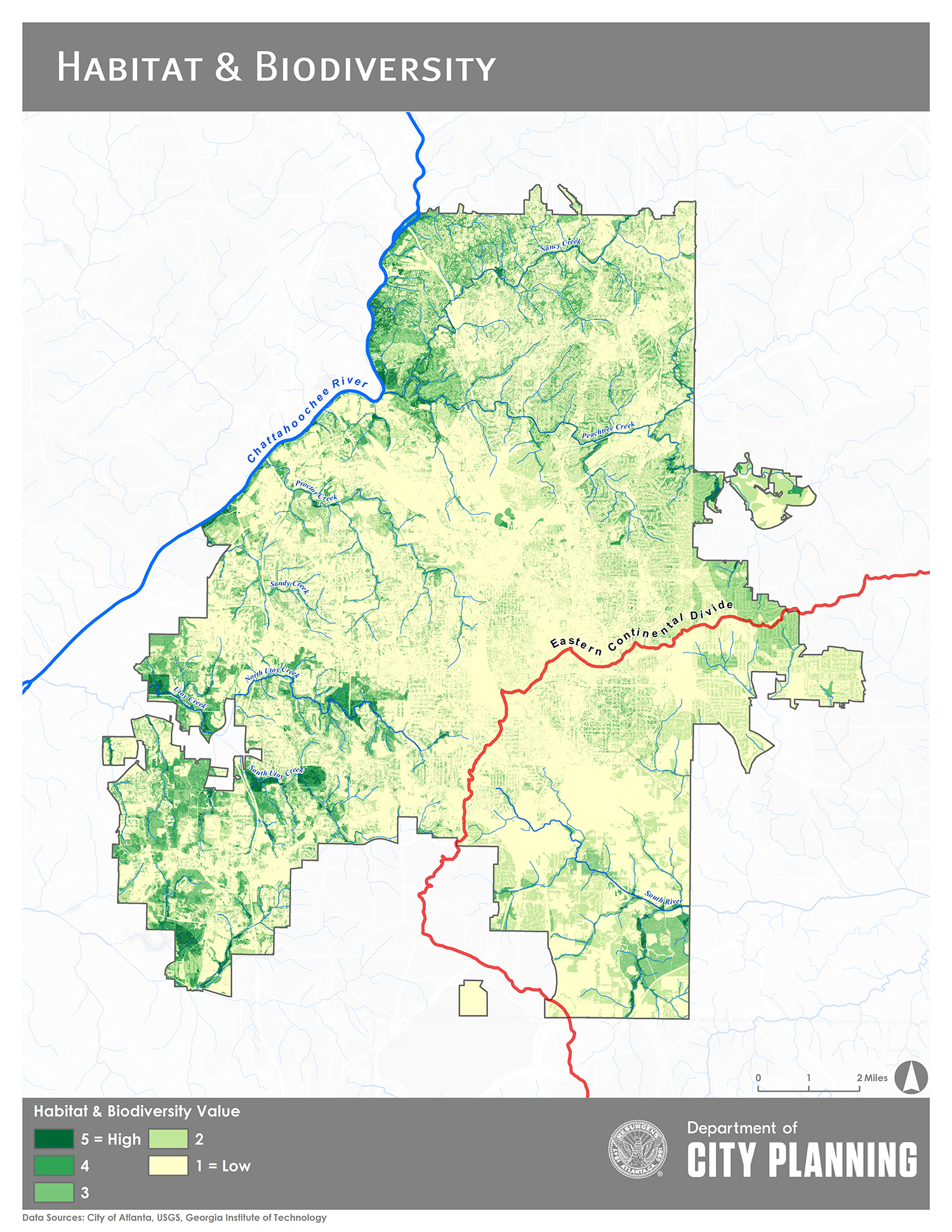

Based on this input, we examine the city through a data-driven analysis of socio-ecological conditions. We gather data on soils, hydrology, landcover, habitat and biodiversity hot spots, floodplain, riparian corridor buffers, and historical streams. Studies of social vulnerability, urban tree canopy change, traffic patterns, safety and access issues are also examined. We perform analysis at multiple scales to ensure consideration of broader impacts to ecoregions, wildlife and habitat corridors, and watersheds. We also endeavor to uncover the historical patterns of nature that settlement may have disrupted.

Once the general conditions have been mapped and vetted with the community, our team delves deeper and explores ways to harness the natural patterns and processes inherent in the local ecosystems to address the vision and goals established at the outset of the process, whether that is increasing access to open space, utilizing vacant lots for revitalization and restoration, managing climate change impacts, focusing development and preserving tree canopy, or other socio-ecological aims. In Baltimore, through the initial data analysis, we identified four priority areas that had overlapping needs for revitalization and ecological uplift potential, very high densities of vacant land and structures, and very active and engaged neighborhood groups. In the case of Atlanta, we examined the need for habitat and biodiversity protection, harnessing ecosystem services, increasing equitable access to parks and open space, and addressing vulnerable communities’ needs.

Our team connects with residents, local advisors, and advocates at regular intervals to confirm and vet the evolving framework. In Atlanta, as the needs and priorities became clearer, we began testing alternative future scenarios of change with the community. We explored citywide change scenarios associated with improved equity and access, increased ecological connectivity and function, and conversion of all grey infrastructure to innovative green practices. This allowed everyone to visualize patterns of change that could result from different priorities in land use allocation. This pulling apart of key priorities and weaving them back together through the community feedback process provided a powerful visual tool for honing the elements of the urban ecological framework.

From the personal stories shared by community members during the visioning and goal-setting to the input given in other stages of the process, it becomes evident that place—neighborhood, block, home, and all that surrounds it—is inextricably linked to identity. This connection, in turn, becomes a guide for a city’s plans for future development and growth, rather than an afterthought. What has resulted is an acknowledgement that a city’s infrastructure can take more cues from nature and community. A final urban ecological framework creates a cohesive network of greenspaces, restored ecosystems, and civic spaces that serve both human and nonhuman communities in coexistence. It fosters equitable and safe access to open space and recreation, increased biodiversity and habitat, and a variety of ecosystem services including, urban heat island mitigation, flood attenuation, stormwater management, air quality improvements, pollination, and nutrient cycling.

In the case of Baltimore City, the Planning Department went one step further, and it is a step we highly recommend for all municipalities. In each of their four focus areas, Planning Department staff who work with the neighborhoods identified specific community groups and advocates to guide the design of pilot projects. Residents worked directly with the planning team to develop site-specific concepts that reflected their needs. They identified the required programming, types of features, and concerns that should be addressed. In one example, the residents wanted a central, flexible plaza space for community street festivals, a splash pad, a space for watching films, and signage for community notices. In another, the community’s priority was to have a safe space for toddlers to play and a memorial for a fallen female firefighter who had perished on the site. These designs have continued to evolve, gaining local advocates and partners to help in their funding and implementation, fulfilling a promise to the community.

Cities like Atlanta and Baltimore are exemplary in their use of ecology to guide urban planning, but they are not alone in this approach. Other examples include parallel efforts in Edmonton, Canada and Paris, France; and past efforts in Barcelona, Spain and Hamburg, Germany where city leadership identified opportunities to strengthen green networks to foster greater community resilience. The story of Christchurch, NZ, where a natural disaster led to a unique opportunity for re-envisioning urban planning as part of a massive rebuild effort, is even more striking.

In February of 2011, a 6.3 magnitude earthquake hit Christchurch, resulting in widespread structural damage and loss of life. In the wake of this tragedy, the city took the unprecedented step of holding an inclusive and holistic planning process to inform a multiyear and multibillion-dollar rebuild effort. The resulting Christchurch Blueprint sets out a spatial framework for redevelopment, combining actions for economic, social, and environmental revitalization within a central city framed by open space. The Blueprint includes plans for the Te Papa Ōtākaro/Avon River Precinct, which celebrates the river that flows through the center of the city. Many gathered along the river after evacuation from the surrounding buildings on the day of the earthquake and it now hosts a memorial to those who perished in the earthquake and the rescue efforts that followed. Design and planning work along the Avon corridor has focused on supporting the return of native wildlife like the bellbird, whitebait, and eel through channel restoration and increased native plantings. Today the river is a gathering place and a natural spine along which the city continues to see economic revitalization and strengthened community, as well as the return of the eel and other native wildlife.

When is the best time to consider developing an urban ecological network plan for your city? The answer varies based on a city’s long-term planning process and the immediate issues a community may be facing, but it is always the right time to integrate ecology and nature into urban planning and revitalization efforts. Ideally, this type of planning effort can inform zoning updates, public works planning, park master plans, or transportation plans (that may occur on five to 10-year cycles). This approach can also be integrated into a citywide General Plan or as a stand-alone Urban Ecology Network plan to inform other efforts aimed at economic and climate resilience, environmental equity and justice, and ecological uplift.

There will always be competing priorities in the planning process. The most important step we can take is to listen and then respond in a way that reflects not only the community’s needs but also their stories of identity with, and connection to, nature. There is likely to be a certain level of planning fatigue in many cities. One way to address this is to make sure these plans are actionable and implementable—landing at the site scale and making sure the community sees tangible results. One of the most frequent comments we receive during these processes is that the community members want to see results, not another glossy plan on a shelf. The pilot project process is a great way to do just that, by seeding the energy in the community early and engaging them in a design process that includes potential funding partners.

Another issue we must face head-on is the potential negative impacts that greening (even with the best intentions) can have on a community, including gentrification and displacement. During the planning process, this is bound to come up in discussions with residents. In parallel with planning efforts, municipalities can and should be exploring systemic changes that provide economic security to longtime residents in these communities, such as tax abatement options, housing security, land trusts, legacy community designations, and other options to deter displacement and support historic ties between the community and the land.

Ideally, the final urban ecology framework becomes a reference for all future planning efforts, a living reminder of the connection between the native ecology and the human spirit that animates the city, and an amplifier of community voices and identity.

Jennifer Dowdell

Baltimore, MD

Leave a Reply