We urge urban forestry advocates to not forget about the suburbs when planning tree planting actions to increase tree equality. Suburban neighborhoods that are low-income or with many people of color may be important places to focus efforts to increase tree canopy if we are to aim for a city in which all households have adequate nature nearby.

My colleagues and I recently published a paper mapping tree inequality across the United States, to answer some simple questions: How widespread tree inequality? Where is it worst?

We measured the extent of tree cover inequality and its effect on temperatures for almost 6,000 communities across the United States. We were able to use open-source cloud computing on the Google Earth Engine Platform to map tree cover and summer surface temperatures at a 2m resolution, overlaying this information with US Census data on income, race, and ethnicity.

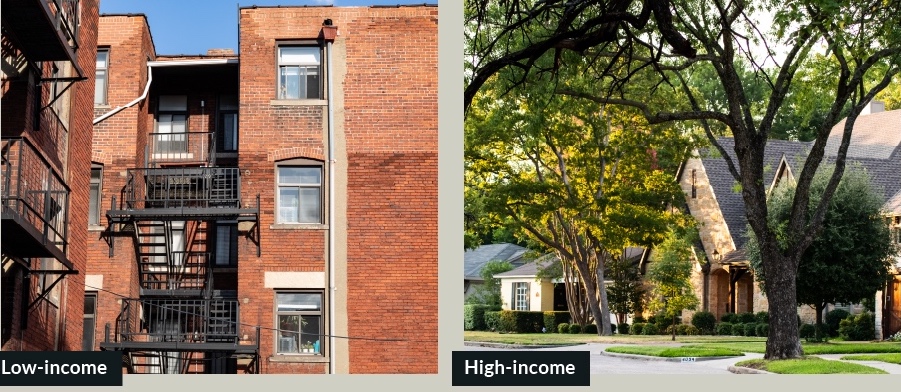

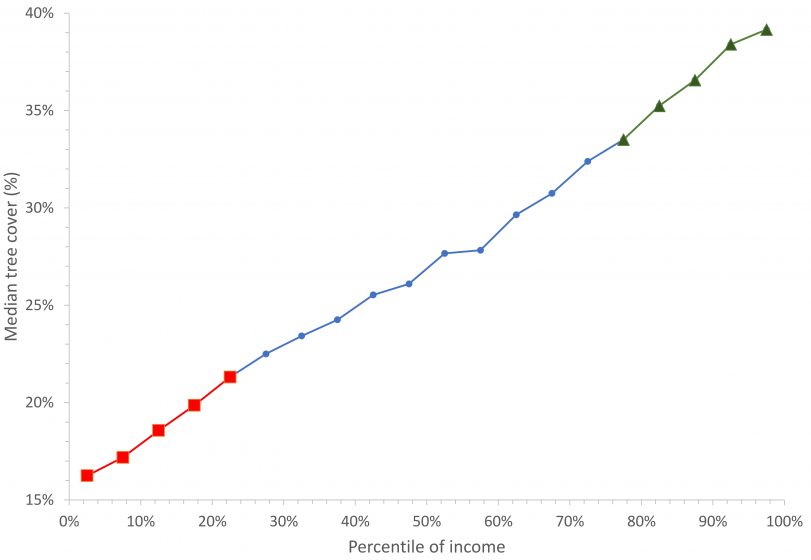

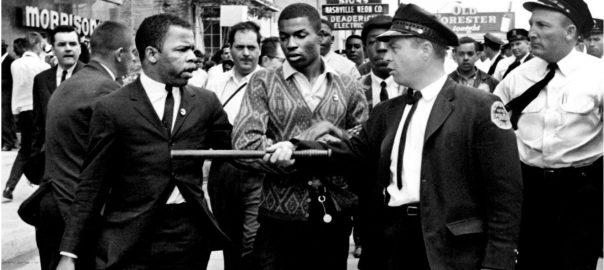

Tree inequality was ubiquitous. In 92% of US cities, low-income neighborhoods have less tree cover than high-income neighborhoods. The rich have, on average, about 15% more tree cover and live in neighborhoods that are around 1.5⁰C coolerthan the poor. This trend extends to race as well: in 67% of US communities, people of color (POC) neighborhoods have less tree cover than white neighborhoods, even after accounting for trends in income. Perhaps not surprisingly, we found that the gradient from urban to suburban is correlated with tree cover. In most American cities, richer, predominately white households have fled to the suburbs, which have a lower percentage of their area covered with impervious surfaces and more space for trees. Conversely, low-income and POC households are still predominately in city centers, which have a higher percentage of their area covered with impervious surfaces and thus less space for trees. There are, of course, exceptions to this trend (for instance, many neighborhoods in Manhattan are dense, rich, predominately white, and have a lower tree cover than the other boroughs of New York City), but in general one reason low-income households have less tree cover is that they live in denser neighborhoods than high-income households. There are, of course, many other reasons for tree inequality that other scholars have pointed out, such as historical patterns of de jure segregation, redlining practices, and other explicitly or implicitly racist decisions.

Perhaps not surprisingly, we found that the gradient from urban to suburban is correlated with tree cover. In most American cities, richer, predominately white households have fled to the suburbs, which have a lower percentage of their area covered with impervious surfaces and more space for trees. Conversely, low-income and POC households are still predominately in city centers, which have a higher percentage of their area covered with impervious surfaces and thus less space for trees. There are, of course, exceptions to this trend (for instance, many neighborhoods in Manhattan are dense, rich, predominately white, and have a lower tree cover than the other boroughs of New York City), but in general one reason low-income households have less tree cover is that they live in denser neighborhoods than high-income households. There are, of course, many other reasons for tree inequality that other scholars have pointed out, such as historical patterns of de jure segregation, redlining practices, and other explicitly or implicitly racist decisions.

What is perhaps more interesting for readers of TNOC is the question of where tree inequality is the worst. When you compare neighborhoods at the same population density, you find that there is still a clear effect of income and race. High-income and white neighborhoods have more tree cover than equivalently dense low-income and POC neighborhoods. Surprisingly (at least to us!), the inequality in tree cover is greater in low-density neighborhoods than in high-density neighborhoods. For instance, for neighborhoods in the Very Low population density category (below 2000 people per square km), which is typically single family homes on large lots in suburban style developments, there was a gap of 7.5% in tree cover between high- and low-income areas. In the Moderate density category (4,000-8,000 people per square kilometer), there was only a gap of 1.9% tree cover. And for the High Density category (>8000 square kilometers), the trend is actually revered: low-income neighborhoods have slightly more (1.5%) tree cover than high income neighborhoods do.

Why then does tree inequality look stronger in the suburbs than in city centers? There are at least two possible reasons. The first is a technical/statistical reason. In low-density neighborhoods, there is a greater fraction of the neighborhood that is not impervious surface cover, and so there are lots of places where trees could in principle be planted. There means there is a large range of observed forest cover, from 0% to above 50% in some neighborhoods. Conversely, in high-density neighborhoods, a greater fraction of the land is impervious, so that is a limit to how many trees could in principle be planted. This means there is a small range of observed forest cover, from 0% to around 10%. This limited range makes it more likely the difference in tree cover between rich and poor neighborhoods will be smaller.

The second is causal reason. Commonly, in the urban core where people live at high density, a greater fraction of the land area is in public ownership, either as parks or as part of the road right of way, as compared to lower density blocks in the suburbs or in rural areas. While there certainly have been recorded cases of differences in municipal investment in public tree planting between rich and poor neighborhoods, whether through discrimination or just through neglect, much of the urban tree cover is the result of public sector management choices. To the degree cities have programs that are supplying this public good (urban tree cover), they may be trying to equalize tree cover provision between neighborhoods. Conversely in the suburbs and exurbs, a greater fraction of the land area is under private ownership than in higher density blocks. Thus, tree cover in the suburbs is particularly shaped by the actions of private landowners. We speculate that low-income households may be less able to afford the cost, in money and time, of planting trees and maintaining them. Moreover, low-income households are more likely to be in rental units and are thus likely less involved in making decisions about land management. Owners of these rental units are primarily interested in reducing maintenance costs and thus may have less of an incentive to plant and maintain trees than the unit’s residents.

Whatever the reason for the trend toward greater tree inequality in the suburbs, we urge urban forestry advocates to not forget about the suburbs when planning tree planting actions to increase tree equality. Our research suggests that low-income and POC suburban neighborhoods may be an important place to focus efforts to increase tree canopy if we are to aim for a city in which all households have adequate nature nearby.

Rob McDonald

Washington

Leave a Reply