In November 2021, New Yorkers overwhelmingly voted to add an environmental amendment to their state constitution. Section 19, which provides that “Each person shall have a right to clean air and water, and a healthful environment,” is now part of the New York Bill of Rights (the part of New York’s constitution that defines individual liberties and the limits of state power). This language is both sweeping and simple. It guarantees all New Yorkers the constitutional right to live, work, and play in communities that are safe, healthy, and free from harmful environmental conditions. As Steve Englebright, the amendment’s primary sponsor in the state assembly, explained: “the right to clean air and clean water and a healthful environment is an elementary part of living in this great state.” Just to give some perspective on how momentous this moment is, the last time any state amended its constitution to recognize environmental rights was 1971 when Pennsylvania voters voted overwhelmingly to add Article I, Section 27 to their constitution.

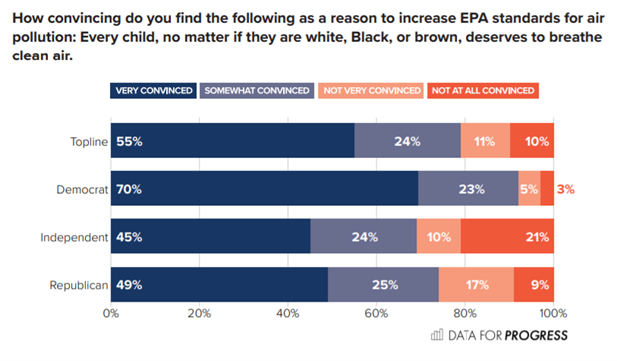

The final vote adopting this amendment indicated wide political support for environmental rights—the proposal to add Section 19 to the New York constitution garnered just over 70% support from voters, a greater than 2:1 margin. And, before being added to the ballot, the proposed amendment first had to twice pass both houses of the state legislature—something it also did by an overwhelming margin. This amendment clearly and unambiguously reflects the will of the people of New York. In this, New York is part of a broader social consensus on environmental rights across the United States and around the world.

In the Fall of 2021, just before New York adopted its environmental amendment, the United Nations Human Rights Council voted overwhelmingly to recognize the right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment as a universal human right. In the Spring of 2022, the UN General Assembly as a whole will consider a similar resolution recognizing the human right to a healthy environment. Appropriately, this vote will take place in the UN’s New York headquarters—bringing environmental rights full circle. The New York City Bar Association has long been a vocal supporter of this UN resolution.

What does it mean to amend the state constitution?

The United States has a federal system in which both states and the national government have constitutions. The federal Constitution’s Bill of Rights, which applies to the states through the 14th Amendment, defines the minimum constitutional rights that must be accorded to every person in the United States. While States cannot use their constitutions to deprive individuals of the minimum federally guaranteed rights, they may add additional protections. With this amendment, New York has expanded the fundamental rights of New Yorkers to include the right to a healthy environment.

When the “forever wild” provision was added to the New York constitution in 1894, New York became the first state in the Union to include environmental protection in its state constitution. By enacting Section 19, New York has once again placed itself as the vanguard of green constitutional amendments, but it is far from alone in its embrace of environmental rights. Montana, Pennsylvania, and, to a lesser extent, Hawaii, Massachusetts, and Illinois recognize environmental rights, as do the national constitutions of well over 100 countries. The United Nations Human Rights Council recently recognized the right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment as a universal human right.

How will this amendment promote environmental justice?

Section 19 is a clear recognition that environmental rights belong to everyone—that no people and no neighborhoods can be sacrificed on the altar of economic growth.

Section 19 is a clear recognition that environmental rights belong to everyone—that no people and no neighborhoods can be sacrificed on the altar of economic growth.

By grounding environmental rights in the state constitution, New Yorkers have committed their state to a new path forward—one based on environmental justice. Environmental justice involves both fair treatment and meaningful involvement of communities in decisions by which environmental choices are made.

The constitutional rights enshrined in Section 19 give substantive heft to procedural rights that have long been a part of environmental decision-making under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and the State Environmental Quality Review Act (SEQRA.) These existing laws are focused on creating a pathway for public participation in decision-making processes largely in order to prevent “uninformed rather than unwise” decisions. By contrast, the substantive environmental rights enshrined in Section 19 put issues of fair treatment—how environmental burdens and benefits are actually distributed—squarely on the table.

With the adoption of Section 19, the right to clean air, pure water, and a healthy environment are now on equal constitutional footing with the right to property (Art. I, §7), to petition the government (Art I, §9), freedom of religion (Art, I, §3), and freedom of speech (Art. I, §8). Like these other constitutionally-protected fundamental rights, Section 19 delineates self-executing rights (meaning they can be claimed without additional implementing legislation) that the government can neither deny nor infringe. Every person holds these environmental rights by virtue of being in New York, and Section 19 applies whenever state action might impede those rights. It imposes constraints on what the government can do vis-à-vis environmental rights as well as on how the government must make decisions. All agencies and local governments will need to ensure their decisions take full account of environmental rights. In short, public officials of all stripes must embed protecting environmental rights into the fabric of all governmental workways.

Moreover, this amendment shifts the baseline for considering environmental (in)justice. For far too long, New York’s Black communities, communities of color, and low-income communities have borne far more than their fair share of the environmental burdens, with pollution disproportionately and systematically impacting their communities. They have had to fight tooth and nail for basic environmental rights. Poor communities, and communities of color, bear the brunt of polluted air, unsafe water, and the growing impacts of climate change.

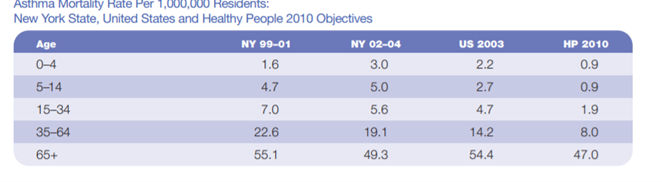

Nearly a century ago, structural racism in the form of redlining intentionally cut Black and brown communities out of the New Deal and out of the economic prosperity it built. New York compounded this legacy of structural racism by steering most of its polluting infrastructure into these same communities, and then by failing to protect those communities with rigorous environmental enforcement. As a result, a Black child in New York is 42% more likely to have asthma than a white child, eight times more likely to be hospitalized for asthma-related ailments, two or three times as likely to miss days of school because of asthma. Across the state, Black New Yorkers are nearly four more likely to die from asthma-related complications.

The same grim disparities hold true for cardiovascular and pulmonary disease, which are also closely related to pollution. Recent studies have shown how increased exposure to pollution heightens the risks posed by COVID-19.

Section 19 must be read in combination with the pre-existing guarantees of equal protection under law and the prohibition of discrimination (Art. I, §11). To fulfill their interrelated constitutional duties of equal protection and respecting environmental rights, all government actors, from courts to legislators and regulators, will have to prioritize protecting the most vulnerable from pollution, degradation, and climate change, and ensuring that environmental burdens are not heaped on already overburdened communities.

As such, this amendment is a momentous step forward for environmental justice. It provides a context and platform for raising disparate health and environmental outcomes associated with governmental decisions about polluting activities, and for challenging unequal protection under, or enforcement of existing law. It also requires a rethinking of public participation to ensure that those most affected by environmental decisions have a genuine opportunity for meaningful participation in a decision-making process that takes their environmental rights seriously.

What will this amendment mean in practice?

The challenge will be turning law on the books into change in the world and ensuring that this constitutional change marks the end of business as usual for polluters. If we are successful, Section 19 will mark the beginning of a new era in which human wellbeing and planetary health are the priorities. Nearly a century ago, in New Jersey v. City of New York, the United States Supreme Court explicitly found that issuance of a permit could not prevent a court from enjoining conduct that created an environmental nuisance. Much the same way that a permit is not a defense to a claim sounding in nuisance, a permit will similarly not insulate ongoing conduct from constitutional scrutiny. Article 19 thus opens a pathway for reconsidering past governmental decisions that unduly discounted environmental concerns or did not fully value environmental rights. New York now has both the authority and the duty to ensure that environmental rights are respected. For that to happen, behaviors must change in all branches of government.

Executive Branch

The New York Constitution tasks the Governor with the duty to “take care that the law be faithfully executed.” Article 1, Section 19, now provides a constitutional foundation for all New York’s laws affecting the environment. To faithfully execute the environmental amendments, the state must issue new environmental guidance for interpreting existing law and regulation and will need to enact new regulations designed to promote, protect, and defend environmental rights.

The state has an unambiguous mandate to protect New Yorkers’ right to breathe clean air, drink clean water, and live and work in a healthy environment. Everyone exercising governmental authority, including agencies and local government, has an obligation to protect environmental rights, to promote actions designed to preserve and enhance these rights, and to take affirmative steps to provide a healthy environment to all New Yorkers, including intervening when these rights are jeopardized. Protecting clean air and water must shape how all state law is interpreted and applied. State actors will have new grounds to justify more rigorous enforcement or to defend state environmental legislation from attack by polluting industry.

The state has an unambiguous mandate to protect New Yorkers’ right to breathe clean air, drink clean water, and live and work in a healthy environment. Everyone exercising governmental authority, including agencies and local government, has an obligation to protect environmental rights, to promote actions designed to preserve and enhance these rights, and to take affirmative steps to provide a healthy environment to all New Yorkers, including intervening when these rights are jeopardized. Protecting clean air and water must shape how all state law is interpreted and applied. State actors will have new grounds to justify more rigorous enforcement or to defend state environmental legislation from attack by polluting industry.

Section 19 also gives states more flexibility to act in response to emerging environmental threats that might not yet be subject to regulation. This will be particularly useful when responding to threats posed by new chemical compounds. For example, had this constitutional amendment been in place earlier, it would have given New York clear grounds to take actions in Hoosick Falls to remedy PFAS water contamination once it became clear that the pollution was negatively impacting environmental rights. New York would not have to wait for regulations specifically targeting a particular chemical before holding polluters responsible.

Perhaps the most sweeping changes will be in how governmental actors conduct environmental impact assessments and/or consider environmental costs and benefits in decision-making. State actors will need to ensure that their decisions (vis-à-vis e.g. siting, transportation, development, and permitting) fully respect environmental rights. Section 19 necessitates that agencies and local planning boards strike a new balance when environmental rights and property rights (or economic development proposals) conflict. Where DEC previously interpreted SEQRA to allow permit denials “if the adverse environmental impacts cannot be favorably balanced against social and economic considerations,” this amendment now puts a thumb on the scale for protecting the environment.

The Judiciary must assess whether government action has violated these rights

The Judiciary must assess whether government action has violated these rights

Section 19 will greatly expand the range of people able to establish standing to bring challenges to government decisions about the environment. Because litigants can now allege that their fundamental constitutional rights have been violated, Section 19 will make it easier to challenge government actions with negative environmental impacts. In particular, the new amendment will facilitate new environmental justice challenges—allowing overburdened communities to allege that governmental action (or inaction in the case of failure to enforce permits) unduly infringes on environmental rights. Under Section 19, a court will have to satisfy itself that a challenged government action adequately protects and respects environmental rights. Where that is not the case, courts can impose the full panoply of equitable remedies that might be needed to ensure that environmental rights are honored.

Section 19 will also change the way that courts evaluate the adequacy of governmental decision-making processes by which environmental choices are made. As the United States Supreme Court explained in Cleveland Board of Ed v. Loudermill, the state definition of fundamental rights like property or liberty give rise to constitutional due process requirements. Once a state creates such an interest (and there is no better way to create than via constitutional amendment), no one can be deprived of their liberty/property interest without due process of law, nor can it be taken without just compensation. New York must treat environmental rights akin to property rights—deprivation of which can happen only after due process and with just compensation. This principle should serve as a guide to agencies in interpreting their duties under the myriad state laws and regulations.

The Legislature

As the clearly expressed will of the people vis-à-vis environmental rights, Section 19 will both constrain and guide legislative action. The amendment provides a floor below which environmental protections cannot sink, and all laws will have to take account of that environmental floor. This will be true for existing law, which may have to be amended to bring it into harmony with Section 19. Going forward, Section 19 offers important guidance to New York’s legislature as it debates a wide range of new legislation across a host of topics including eliminating structural racism, criminal justice reform, public education, transportation and energy needs, housing and development, and climate change. Environmental equity provisions like those built into the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act will become the standard for how to move forward with legislation that affects and concerns the environment.

Rebecca Bratspies

New York

Thank you for this article. While it clearly states the law’s intent, it does not state how the law interprets the mechanisms that afford the ability to breathe clean air. drink clean water and live and work within a healthy environment.

• For example, does it recognize that trees, be they in the forest or in a city’s streets, are a major provider of clean air and that, as a result, healthy trees should not be cut down on a whim? New York City has all sorts of ordinances on its books that claim action against climate change and yet their Landscape Architects designed a major landscape revision for Fort Greene Park Brooklyn which will remove 83 trees from the Park, 58 of which have been found to be perfect;y healthy as a result of a Consulting Arborist’s survey. In addition, the re-design of this Olmstead Park will see a great deal of hardscape added, increasing the Urban Heat Island effect – something that the existing tree population was mitigating. The community has been fighting this climate impacting destruction for years.

• Or does it recognize the environmental damage caused by the continued extraction and use of Fossil Fuels? Despite the New York state ban on fracking, National Grid is repeatedly trying to increase its fracked gas pipeline network through North Brooklyn including a vaporizer which will increase methane gas introduction into this mostly disenfranchised community. In addition, fracked gas will be transported via road from Greenpoint to Long Island and Massachusetts, an environmentally hazard-filled undertaking. Even though the Section 19 law is on the books, Governor Hochhul is considering its approval.

Where is the enforceable reality of this law? How does it consider cause and effect or is it just greenwashing??? How do Citizens demand this right when the Government is not upholding their own laws???

•

Germany, Austria, France and the Netherlands have finally come to its senses and realized Green technology, air turbines, and solar will NOT produce sufficient energy to meet the energy demands of their countries. As of 2022 they are restarting coal energy plants to provide electricity and homeowners are building homes with backup fossil fuel for water and heating furnaces. Biden NY Democrats like Governor Hochel are creating a crisis in which fossil fuels will not available or can’t be used to provide NY energy. They are blindly leaving NY without any backup fuel systems should electricity become unavailable or insufficient to safeguard the public.

Without community awareness; and individual responsibility, as business owner and/or resident—section 19 will not be enforceable.

Thank you for this article, which helpfully and powerfully points out legal pathways for redress of harms that were beyond the reach of existing regulation. There are so many polluting facilities have been permitted because DEC has found no significant environmental impact during SEQRA reviews. DEC’s current Environmental Justice accommodation during permitting is “enhanced participation,” which involves only more public disclosure and communication, but no accounting for cumulative pollution impacts. Deficient regulations, regulatory loopholes, and deficient enforcement allow polluting facilities to keep on harming new generations of residents. A timely and important article!