The Nature of Cities was launched 10 years ago, in June 2012. I believe it has been a success, with over four million reads and around 1,000 contributors. I believe it has been valuable in framing and propelling dialogue in its promotion of collaboration and transdisciplinarity that are essential to cities that are better for both people and for nature; cities that are resilient, sustainable, livable, and just.

All four.

Not just the one or two we might pursue from the confines of one discipline, but all four, which can only achieved by reaching beyond the edges of our knowing to engage with someone else’s. Indeed, the wicked problems we so often talk about these days would seem to logically demand similarly rich approach to solutions — that is, transdisciplinary solutions that are as complex and nuanced as the problems.

The three quotes you see to the right knit together, for me, a sense of we can achieve if we (1) seek inspiration in nature; (2) share, collaborate, and innovate with each other; and (3) are fierce with ourselves about the imperative of progress. These ideas have been driving forces in the ongoing evolution of TNOC.

We have published almost 1,300 essays and roundtables in these 10 years, and worked on a variety of projects. I believe that all work at TNOC has great value; the 30 pieces highlighted here represent a selection that were particularly widely read, singular, or key in some way. There are many others that could easily have made this list.

Onward and upward, we can hope. In our work we continue to seek the frontiers of thought and action found at the fizzy boundaries of science. practice, community, design, planning, infrastructure, and art.

Thank you for participating with us over 10 years. Let’s continue to collaborate and act for progress.

* * *

Ten years ago, the birth of TNOC was fired by conversations with many people, but two in particular: Mike Houck in Portland, and Erika Svendsen in New York. From Houck, I received his passion about fierce activism in service of a nature that was right outside the door; an urban nature that wasn’t many miles away, accessible to only a few, but right outside. The idea of accessible nature nearby is foundational to any concept of urban environmental justice. From Erika, I was moved by the idea of people working together in community to create and steward the natural work around them. An urban environment that centers both nature and people is key to any real progress in green and livable cities. Erika, Lindsay Cambell, and Liza Paqueo of the the US Forest Service are among TNOC’s greatest friends.

There are many more people I appreciate for influencing what TNOC has become, growing from 12 writers to over 1,000. First to mention is our board: Mike Houck (Portland); Martha Fajardo (Bogotá); Mark Rowe (Toronto); Marcus Collier (Dublin); Siobhán McQuaid (Dublin); Chantal van Ham (Brussels); Gilles Lecuir (Paris); Pippin Anderson (Cape Town); and Huda Shaka (Dubai) — plus former board members Thomas Elmqvist (Stockholm); Rodolpho Ramina (Curitiba); Valerie Gwinner (Washington/Vaison du Romain); and David Tittle (London). A million thanks also to remarkable core TNOCers M’Lisa Colbert, Patrick Lydon, Carmen Bouyer, Claudia Mistelli, Karen Tsugawa, and Emmalee Barnett.

Finally, thank you to all our sponsors and partners. You can see who they are at the footer of this page.

Donate to TNOC

TNOC is a public charity, a non-profit [501(c)3] organization in the United States, with a sister organization in Dublin (TNOC Europe). We rely on private contributions and grants to support our work, and to demonstrate grassroots support to our organizational funders. No pay-wall exists in front of TNOC content. So, if you can, we could use your help. Click here to donate.

The Nature of Cities Festival

The Nature of Cities Festival

We have presented three large global events at TNOC, starting with TNOC Summit in Paris in 2019. Two versions of an entirely virtual TNOC Festival followed in 2021 and 2022. The common thread in the three was a commitment to having many different ways of knowing and modes of action all at the same meeting. We also, especially in the virtual Festivals, tried to make sure that everyone could participate to disrupt the notion that international urban meetings were only available to the people who can afford them. Key to us is lowering barriers to participation.

Roundtables

Graffiti and street art can be controversial. But it can also be a medium for voices of social change, protest, or expressions of community desire. What, how, and where are examples of graffiti as a positive force in communities?

In many cities, graffiti is associated with decay, with communities out of control, and so it is outlawed. In some cities, it is legal, within limits, and valued as a form of social expression. “Street art”, graffiti’s more formal cousin, which is often commissioned and sanctioned, has a firmer place in communities, but can still be an important form of “outsider” expression.

Corridors have been promoted by conservation biologists to restore connectivity of habitats and to facilitate the movement of plants and animals. The exchange of genetic material between spatially distinct communities has a fundamental impact on ecological processes such as diversity-stability relationships, ecosystem function, and food webs.

Urban green corridors are a good example of where we jump ahead to solutions before defining the problem. Before calling for the establishment or protection of corridors, it’s important to consider what kinds of ecological and social objectives we want in our cities. I think that green corridors have great potential because they can perform multiple functions. However, exactly what these desired functions are needs to be clearly defined first before guidelines for their design can be set.

Artists and scientists that co-create regenerative projects in cities? Yes, please. But how?

Artists and scientists that co-create regenerative projects in cities? Yes, please. But how?

We asked a collection of scientists and artists, each actively engaged in some form of art-science collaboration, how they approach it. Some are artists, some are scientists, some are both. All are interested in exploring a fizzy boundary of expression at the intersection of artistic and scientific approaches to storytelling.

Key to the question of this roundtable: can we be changed by interactions with other ways of knowing, changes in ways that would enrich both useful knowledge and our interdisciplinary practice?

Urban agriculture has many benefits. Is one of them a contribution to urban sustainability?

Sustainability is key to our future, and, as urbanization steadily grows, keys to increased global sustainability must be found in cities and how they use and are provided with resources. In this area there has been much excitement about urban agriculture, which for our purposes here we will define as the production of food in and near cities at scales larger than home or community gardens.

There are many potential benefits to such efforts, including the support of social movements; economic development; creation of local businesses and jobs; environmental education; community building; and local food security. But does urban agriculture have the potential to contribute significantly to urban sustainability by reducing cities’ dependence on food grown at great distance from the city? Can it produce enough to address food insecurity?

Are cities ecosystems in the senses in which we think of classic natural and ecological areas outside of cities? After all, urban spaces are connected mosaics of green space, biodiversity (including people), non-biological structure, biophysical processes, energy flows, and so on. That sounds a lot like a natural ecosystem.

But perhaps more importantly, does thinking explicitly about cities as ecosystems help us? Does it offer us any insight into urban design? For example, are our goals for cities—sustainability, resilience, livability, and justice—advanced by an urban ecosystem concept?

Many of the benefits of green roofs are appreciated and increasingly well-studied: stormwater management, mitigation of heat islands, insulation, biodiversity, increased longevity of the waterproof membrane, green space for enjoyment, and so on.

With all these benefits, why don’t more buildings—especially large ones—have green roofs? Shouldn’t they? Should all public buildings and large new construction be required to have green roofs?

Answering these questions obviously requires complicated technical and political calculations about the real and perceived values of green roofs, what they cost to build and maintain, and whether greens roofs are “worth it”.

We are all confined to our homes—if we are lucky. Which is something, since most of us are “outdoor types”, “people types”. Can we find meaning, motivation, and renewed spirit for action in this contemplative but deeply strange time? We find ourselves wondering, doubting, planning our next steps or perhaps second-guessing our last ones. We are trying to keep all the parts of lives still stuck together and not flying apart.

Now that we have seen how our cities around the world truly function at their most vulnerable, what possible excuse do we now have to not emerge solely committed to fixing it? Maybe in searching for a new post-Covid “normal”, we need to act on the idea that the old normal was a big part of the problem.

You say po-TAY-to. What ecologists and landscape architects don’t get about each other, but ought to.

You say po-TAY-to. What ecologists and landscape architects don’t get about each other, but ought to.

In the creation of better cities, urban ecologists and landscape architects have a lot in common: to create and/or facilitate natural environments that are good for both people and nature. Mostly. Some may tilt toward the built side, some to the wild. Some may gravitate to people, others to biodiversity, form or ecological function, or social function, or beauty.

There are a lot of shared values. And yet, they are still two distinct professions, ecology and design, and so there are ways in which we may say similar sounding things but mean something different. What is something your partner in environmental city building, the other profession, just doesn’t get about you? And what would it take it fix it?

Artists in Conversation with Water in Cities

As human beings who inhabit bodies made mostly of water, connecting to water as an element means connecting to a large part of who we are. Yet more than this, the artists in this roundtable teach us that if we pay close attention, water can help us connect in profound and useful ways to the environments around us.

Water is vital, spiritual, and restorative. It is a common that connects us all, to each other, and to our biosphere. The conversations here take various forms, from the performative to the media-based, from poems to sculptures to design, and from community and civic engagement, to methods of collaborative caring for water and for each other. We are pleased to have you discover these conversations with us, and invite you to further enrich them by responding to the work and perspectives together.

Common threads: connections among the ideas of Jane Jacobs and Elinor Ostrom, and their relevance to urban socio-ecology

Common threads: connections among the ideas of Jane Jacobs and Elinor Ostrom, and their relevance to urban socio-ecology

Jane Jacobs and Elinor Ostrom were both giants in their impact on how we think about communities, cities, and common resources such as space and nature. But we don’t often put them together to recognize the common threads in their ideas.

Jacobs is rightly famous for her books, including The Death and Life of Great American Cities, and for her belief that people, vibrant spaces and small-scale interactions make great cities—that cities are “living beings” and function like ecosystems. Ostrom won a Nobel Prize for her work in economic governance, especially as it relates to the Commons. She was an early developer of a social-ecological framework for the governance of natural resources and ecosystems. These streams of ideas clearly resonate together in how they bind people, economies, places, and nature into a single, ecosystem-driven framework of thought and planning

We have assembled a list of 90 must-reads on cities from a diverse group of TNOC contributors—a nature of cities reader’s digest. The recommendations are as wide-ranging as the TNOC community, from many points of view and from around the world. They are a reflection of the breadth of thought that cities need. And, as my grandmother would have said: “This will keep you off the street and out of trouble”.

The prompt seems easy, but it turns out to be difficult to recommend the one thing everyone should read on cities, and what we have created here is a remarkable and diverse reading list. You will likely think of other essential works yourself, and when you do, leave them here as a comment.

Beyond equity: What does an anti-racist urban ecology look like?

There has been a growing belief in the need for “equity” in how we build urban environments. The inequities have long been clear, but remain largely unsolved in environmental justice: both environmental “bads” (e.g. pollution) and “goods” (parks, food, ecosystem services of various kinds, livability) tend to be inequitably distributed. Such problems exist around the world, from New York to Mumbai, from Brussels to Rio de Janeiro to Lagos. Indeed, among many there is a sense that “equity” is not enough. Perhaps we need a more active expression of the social and environmental struggles that that underlie issues of equity and inequity in environmental justice and urban ecologies: one that is explicitly “anti-racist”, and which recognizes and tries to dismantle the systemic foundations of the inequities.

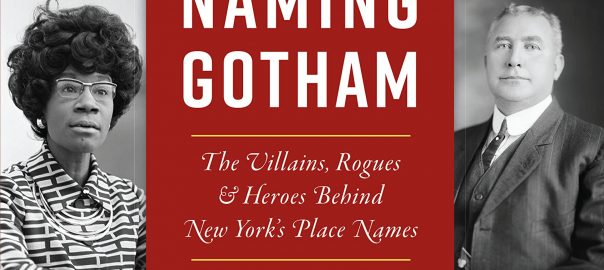

The Just City Essays

The Just City Essays: 26 Visions for Urban Equity, Inclusion and Opportunity was a collaboration of the J. Max Bond Center on Design for the Just City at the City College of New York, The Nature of Cities, and Next City; funded by the Ford Foundation. It has been among the most widely read publications at TNOC, and among other things, was the required reading of all freshman at Stanford University in 2019.

Art and Exhibits

As COVID-19 began, The Urban Ecological Arts Forum at The Nature of Cities, sometimes known as FRIEC, started bringing to life virtual exhibition spaces, highlighting current exhibitions on urban ecological themes that would otherwise be impossible to experience due to the closure of cultural facilities. We have expanded this idea of a regular series or “installations” that traverse the shared frontiers of art, science, and practice. This commitment to art engagement has expanded to fiction, poetry, comics, graffiti, and, in collaboration with the US Forest Service, artist residencies.

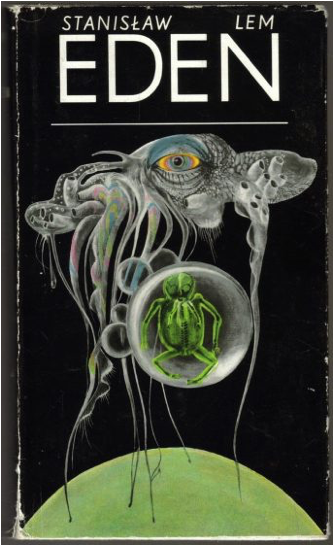

City in a Wild Garden: Stories of the Nature of Cities, Vol. 2

This is our second volume of short fiction about current and future cities. We wanted to explore how to imagine cities. We asked authors to be inspired by an imagining, an evocative phrase: “City in a wild garden.” In this volume, there are stories of transformation, loss, and despair, and also stories of great beauty and hope, with nature and people that emerge from trials, in which people and the wild have merged in fundamental ways. Forty-nine stories from 20 countries are in this book, including the six that we judged to be “prize-winners,” by authors from the United States, India, and Brazil.

SPROUT: An eco-urban poetry journal

SPROUT is an eco-urban poetry journal that curates space for trans- and multi-disciplinary collaborations between poets, researchers, and citizens with a focus on geographical diversity, polyvocality, and translation. For the first volume, in inviting new work to reflect expansively about space, the contributors took up the call to carve out space(s) for themselves. The collected product reflects a multitude of poetic practices. What brings them all together is a particular attentiveness to the liminal, the in-between, the beingness of being-in-space, and acts of seeing out (or, indeed in) wards, into space.

Hidden Flows — photographers uncover the invisible flows in African cities

The hidden flows exhibition emerged out of a need to enrich current conversations about resources, infrastructure and services in African cities. There is ongoing research, through the lens of urban metabolism, to measure and track how resources flow through our cities, in order to support decision making and policy generation. Traditional urban metabolism research approaches rely on extensive quantitative data. Gathering these data accurately is difficult in most cities and even more so in African contexts because of the way resources move – not through typically piped and cabled network infrastructures – but in ways which are reliant on decentralized systems and on private [informal] individuals and organizations.

NYC Urban Field Station—Who Takes Care of New York?

This exhibition was originally mounted at the Queens Museum in September 2019, and highlights the stories, geographies, and impacts of diverse civic stewards across New York through art, maps, and storytelling. The virtual iteration which you are about to experience is provided through a collaboration between the Forum for Radical Imagination on Environmental Cultures (FRIEC) at The Nature of Cities, and the USDA Forest Service, NYC Urban Field Station.

The show features artists whose work aligns with the themes of community-based stewardship, civic engagement, and social infrastructure: Magali Duzant, Matthew Jensen, Jodie Lyn-Kee-Chow, and Julia Oldham. Through photography, drawing, book arts, and performance, these artists reflect upon, amplify, and interpret the work of stewards and the landscapes and neighborhoods with which they work.

Shade in the City: Rising Heat Inequity in a Sunburnt Era

To tackle the issue of urban heat, a group of 18 artists and activists in Los Angeles’ vibrant Highland Park neighborhood raised awareness of shade as an equity issue in an outdoor public art installation called Shade in LA | Rising Heat Inequity In A Sunburnt City.

In a warming world, shade equity is an issue that disproportionately affects low-income and working-class communities, people of color, and communities in developing nations who are more likely to work outdoors, rely on public transportation, and live in denser neighborhoods with a lack of trees and shade.

Nikki Lindt—The Underground Sound Project

Nikki Lindt—The Underground Sound Project

The Underground Sound Project, featured on CBS Mornings, is a collection of underground sound recordings made by artist Nikki Lindt over the course of the past year in the five boroughs of NYC and in rural Cherry Valley, NY. The recordings are made by placing microphones underground, underwater and even inside trees.

The Soundwalk is experienced along the trail in Prospect Park, NY. Along the path you will encounter features, such as a stream, old growth tree, soils, wildflowers, and many more. Via a sign with a QR code at designated locations along the walk, you will be able to experience the corresponding subsurface sounds. The soundwalk can also be experienced remotely with headphones.

Essays

Sense of Place

Sense of Place

Jennifer Adams, New York. David A. Greenwood, Thunder Bay. Mitchell Thomashow, Seattle. Alex Russ, Ithaca

A place may also conjure contradicting emotions—the warmth of community and home juxtaposed with the stress of dense urban living. Sense of place—the way we perceive places such as streets, communities, cities or ecoregions—influences our well-being, how we describe and interact with a place, what we value in a place, our respect for ecosystems and other species, how we perceive the affordances of a place, our desire to build more sustainable and just urban communities, and how we choose to improve cities.

Hammarby Sjöstad — A New Generation of Sustainable Urban Eco-Districts

Maria Ignatieva, Uppsala. Per Berg, Sweden

Hammarby sjöstad (Hammarby Lake City) is an urban development project directly south of Stockholm’s South Island. This is no doubt the most referenced and visited spot among Scandinavian examples of implemented eco-friendly urban developments. Today, the Lake City offers a more sustainable framework for everyday life compared to the average Swedish city but hardly challenges its inhabitants to lead a more resilient life.

Vacant Land in Cities Could Provide Important Social and Ecological Benefits

Timon McPhearson, New York

Vacant land has been overlooked for far too long. If cities were to invest in the social-ecological transformation of vacant land into more useful forms, they would be creating the potential to increase the overall sustainability and resilience of the city. Depending on the kinds of land transformations urban planners and designers dream up, vacant land could provide increased green space for urban gardening and recreation, habitat for biodiversity, opportunities for increasing water and air pollution absorption and many other regulating, provisioning, and cultural ecosystem services.

Four Ways to Reduce the Loss of Native Plants and Animals from Our Cities and Towns

Mark McDonnell, Melbourne. Amy Hahs, Ballarat

The actions we undertake under the banner of “creating biodiversity-friendly cities” are about more than just conservation, they are about managing urban biodiversity in a broader sense. Frequently in our discussions of this topic, two distinct but interdependent ideologies tend to emerge. First, we begin by talking about how to preserve the area’s unique plants, animals and ecosystems, which is largely the foundation for the conservation objective in managing biodiversity. However, discussions are increasingly incorporating a second notion, which centres on our motives for managing biodiversity, and in urban areas these are largely expressed as a desire to manage biodiversity for the multiple benefits it provides to people.

The Green Cloud, A Rooftop Story from Shenzhen: A “Living” Sponge Space Inside an Urban Village

Vivin Qiang & Xin Yu, Shenzhen

The Nature Conservancy (TNC), along with other key partners, launched an innovative pilot projec—Green Cloud—on an old building in Gangxia village, transforming its rooftop into a “living sponge” space. The project utilizes three-dimensional light steel structures that are simple to construct and have the capacity to hold over 420 plant containers filled with plants mostly native to Southern China. The original concrete rooftop is transformed by vegetation, which is capable of absorbing and preserving rainwater, creating a nature-based stormwater management system for the residential building, achieving a 65% of run-off control rate. As a result, a living “green cloud” is formed on a rooftop of Gangxia village.

Nature in View, Nature in Design: Reconnecting People with Nature through Design

Nature in View, Nature in Design: Reconnecting People with Nature through Design

Whitney Hopkins, London

Poorly conceived design visibly divided us in urban areas from our wilds and contributed to our recent ability to see nature as something isolated from us. Yet reinvigorating our bond with nature is a challenge architecture and urban design are well placed to address. Architects and designers have control over our built environment; by changing the way we design cities and buildings to connect to rather than disconnect from nature, we can change our proximity to nature and shift our physical relationship to the environment.

Secular, Sacred, and Domestic—Living with Street Trees in Bangalore

Suri Venkatachalam & Harini Nagendra, Bangalore

In rapidly growing Indian cities, change seems like the only constant. Heritage buildings are torn down, roads widened, lakes and wetlands drained, and parks erased to make way for urban growth. Nature is often the first casualty in a constant drive towards development. Yet the street tree stubbornly survives across Indian cities. The lives of street trees are emblematic of the multiple entanglements that characterise the nature-society dialectic animating the ever expanding urban in the global south—entanglements that knit together the past and present, the secular and sacred, and the global and local.

Architecture and Urban Ecosystems: From Segregation to Integration

Kaveh Samiei, Tehran

During modern era of human development, growth of towns and cities displayed a separation between nature and human activities. This was not the case in premodern times, when human settlements either integrated or co-existed peacefully with the nature. The realization that nature embraces the city has powerful implications for how cities are built and maintained and for the health, safety, and welfare of each resident. Social factors are a key component of a viable and healthy eco system.

Though There is Method, There is Madness In It: How Silos of Methods Impede Cross-Cutting Research

Though There is Method, There is Madness In It: How Silos of Methods Impede Cross-Cutting Research

Pippin Anderson, Cape Town

I believe, indeed fear, that until we are happy to really acknowledge the value of each other’s method, any real transdisciplinary engagement, so critical to urban ecology and more broadly global sustainability, will continue to elude us. Simon Lewis (quoted in Zoe Corbyn’s piece “Ecologists shun the urban jungle”), commenting on the failure of ecologists to engage in the social really, calls us on it when he attributes this to the fact that it helps make complex systems more analytically tractable.

In other words, when upacking a complicated multidisciplinary problem, we often have more fealty to the method that to understanding.

They are Not “Informal Settlements”—They are Habitats Made by People

Lorena Zárate, Mexico City

Recognized as a global phenomenon, no country can claim to be free of informal settlements, although the numbers of people suffering can vary largely depending on the region: these problems now affect up to 60 percent of the world’s population—or even more—in some Sub-Saharan African and Southeast Asian cities, and the number of people affected in these locations is expected to double over the next two decades. Neither informal nor irregular, these are, above all, human settlements. Or even better: they are the city produced by the people: the people who claim their rights to live, build, and transform the city.

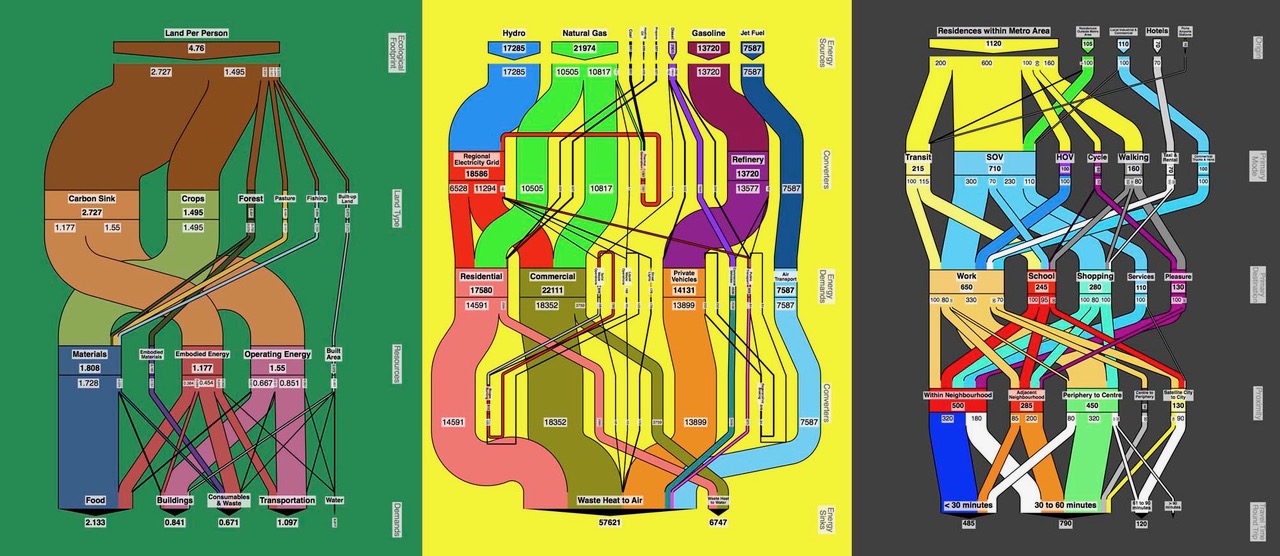

Urban Metabolism: A Real World Model for Visualizing and Co-Creating Healthy Cities

Sven Eberlein, San Francisco

While figuring out the intricacies of our own body’s metabolism is no simple feat, doing a holistic assessment of something as complex as a modern industrial city, with all its physical and cultural microcosms, can seem daunting. With citizen-generated maps and diagrams based on real-life conditions and structured around a holistic framework, the patterns that emerge allow for both residents and planners to ask questions that can lead to both local and regional ecological improvements.

In It Together

In It Together

Lesley Lokko, Accra

The same broad categories of infrastructure, environment, equality and access to amenities apply to all urban centres, almost irrespective of scale. Yet there’s something in—or of/about—The African City that defies easy categorisation. African cities, to paraphrase Soja above, are places where “everything comes together,” in an almost dizzying panoply of contradictory binaries. Black/white; rich/poor; chaotic/controlled; hi-tech/lo-tech, as though there is no space or appetite for the nuance, the in-between, or the subtleties that make up any urban narrative in which most citizens somehow locate, negotiate and recognise themselves.

Crisis Reveals the Fault Lines of Gender in Environmentalism—How Do We Value Everyday Environments?

Nathalie Blanc, Sandra Laugier, Pascale Molinier & Anne Querrien, Paris.

These are times of crisis. One might even think that the COVID-19 crisis looks like a an alternative expression of crises that are already building, especially ecological ones. Neglecting gender and the unequal dimension of access and decision-making rights would doom environmental movements to failure. Let us be imaginative. What does it mean to revisit what the promise of equality means in terms of integrating the importance of gender in socio-environmental inequalities?

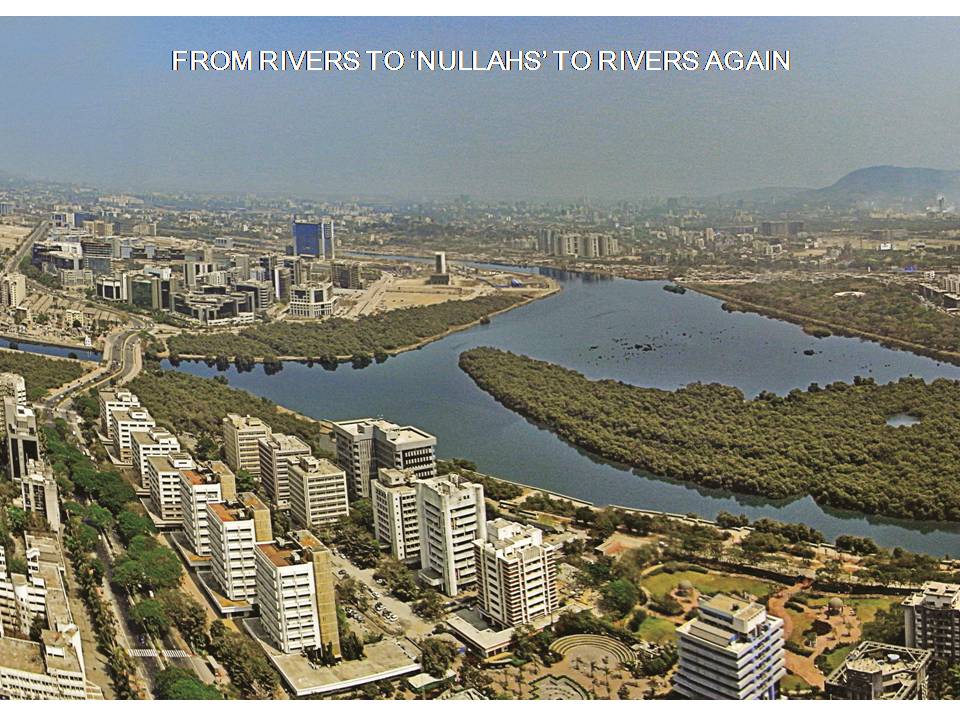

Open Mumbai: Re-envisioning the City and Its Open Spaces

Open Mumbai: Re-envisioning the City and Its Open Spaces

PK Das, Mumbai

41% of the total land area in the densely built city of Mumbai must be reserved as open spaces. A change in the mindset, along with not so radical changes in the development plan, can make this city very eco sensitive and a sustainable urbanized centre to live in. The ‘Open Mumbai’ plan takes into consideration the various reservations in the existing development plan of the city. The recreation grounds, playgrounds, gardens, parks, rivers, nullahs, hills are already marked in the development plan; we are recognizing them and linking them with marginal open spaces and pavements along roads.

Crows of Vancouver: The Middle Way Between Biophobia and Biophilia

Christine Thuring, Vancouver

One of Metro Vancouver’s greatest spectacles is its twice daily crow migration that occurs every dawn and dusk, 365 days a year. Whereas biophilia is a popular meme for urban and ecological design, rarely is biophobia addressed. Perhaps it’s easier to pretend the “undesirables” don’t exist, but that’s just not realistic. The “crows of Vancouver” posed a reality check on the consistency of my narrative. In this era of biodiversity loss and the rising consequences of an over-engineered world our most common species represent an opportunity to reconnect with the dwindling wildness of the Anthropocene.

Water Marks: An Atlas of Water for the City of Milwaukee

Water Marks: An Atlas of Water for the City of Milwaukee

Mary Miss, New York

As an artist, having the opportunity to develop a project at the scale of a city has been a remarkable experience. WaterMarks has grown out of a three-year engagement with the city of Milwaukee. City government, academic institutions, and many nonprofits have been essential contributors to the development of this urban-scaled project. Focusing on water, the project has three important goals in mind: address environmental issues as a gateway to sustainable development; engage communities as active partners; help identify Milwaukee as a global water center. Call and response is a means of dialogue: Physical interventions call out some aspect of the natural systems and infrastructure and, through community engagement activities, the people of Milwaukee respond to and activate the sites.

Hearing from the Future of Cities

Hearing from the Future of Cities

Diana Wiesner, Bogota

Fundación Cerros de Bogotá has been inviting children from Bogota and the surrounding region to paper our walls with their landscape drawings. Last year alone, children from diverse backgrounds sent us more than 2,000 drawings of Bogotá’s mountains and their surroundings. In pondering all of these children’s drawings and listening to their stories about their interests, we began to realize that these children would be our greatest allies in bringing about the changes we have been dreaming about.

Photo Essay: Untold Stories of Change, Loss and Hope Along the Margins of Bengaluru’s Lakes

Photo Essay: Untold Stories of Change, Loss and Hope Along the Margins of Bengaluru’s Lakes

Marthe Derkzen, Arnhem/Nijmegen

Before becoming India’s information technology hub, Bengaluru was known for its numerous lakes and green spaces. Rapid urbanization has led to the disappearance of many of these ecosystems. Those that remain face a range of challenges: residential and commercial construction, pollution and waste dumping, privatization, and so on. Today, Bengaluru’s lakes are principally seen as garbage dumps and sewage ponds that can have either of two fates: one, be transformed into recreational oases to suit the needs of wealthy residential neighborhoods, or two, be encroached upon until none of the original shapes and functions can be traced. But how does this affect the lives of the people living at the very margins of Bengaluru’s beloved yet contested lakes?

Anatomy of a Mural: A Seventy Foot Heron Transforms a Lifeless Wall

Anatomy of a Mural: A Seventy Foot Heron Transforms a Lifeless Wall

Mike Houck, Portland

I frequently lead natural history walks around the 160-acre Oaks Bottom Wildlife Refuge, Portland’s first official urban wildlife refuge that lies on the east bank of the Willamette River, not far from the city center. The mural overlooks the refuge and the tale of its origins invariably intrigues my guests. I certainly learned a lot by working with muralists, artists, building owners, foundations, and the public while helping create the 55,000 square foot wetland mosaic. When it comes to community murals, nothing substitutes for persistence and perseverance. But the results are worth the effort.

Biophilia Revived: How Do We Strengthen the Connection to the Natural Environment in a City Expanding in the Desert

Biophilia Revived: How Do We Strengthen the Connection to the Natural Environment in a City Expanding in the Desert

Abdallah Tawfic, Cairo

I live in a country that lives the dream of conquering the desert and building new cities. Cairo is the second largest city in Africa with a booming population crossing 23 million over an area representing less than 5 percent of the whole country’s land. New ideas such as green roofs could add a decent amount to Cairo’s green spaces, given the huge amount of abundant flat concrete roofs. The idea has triggered the government’s attention in the form of two national campaigns.

Vegetation is the Future of Architecture

Gary Grant, London

There is now a huge and growing body of evidence that green infrastructure or green-blue infrastructure (soil, vegetation, and water) that provides the setting for our cities, provides us with a range of benefits (also described as ecosystem services), including reduction in flooding, purification of air and water, summer shade and cooling, better health and wellbeing, places to relax and mingle, as well as food and habitat for wildlife. Having begun to appreciate the benefits of putting green infrastructure onto buildings, architects, engineers, horticulturalists, and others have developed techniques to do this.

Imagining Future Cities in an Age of Ecological Change

Imagining Future Cities in an Age of Ecological Change

Ursula Heise, Los Angeles

Floating cities. Flying cities. Domed cities. Drowned cities. Cities that flip over once a day to expose different populations to sunlight. Cities underground, in the oceans, or in orbit. Cities on moons, asteroids, or other planets. Cities of memory, of surveillance, or of violence.

Speculative fiction in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries has offered an enormous range of urban visions of the future, many of them dystopian, a few utopian, and quite a few somewhere in between.

For good reason: Cities have taken on a new centrality for human futures.

Time of the Poppies

Time of the Poppies

Andreas Weber, Berlin

What is the essence of a city? What is the kernel of urban civilisation, which, as we know, is engulfing the planet? Urban life is spreading from a minority’s lifestyle to be the predominant fate of human and increasingly nonhuman beings. As I thought in a first glimpse, being stopped at that glowing traffic island, the essence of a city is a constant immersion of everything and everybody in human affairs.

The Shape of Water, the Sight of Air, and Our Emergence from Covid

Lucie Lederhendler, Brandon

I have been working on a mind map of emptiness, inspired by an old Wiccan meditation practice of gazing into a bowl of water and trying to see the middle of the water. In the middle of a large sheet of newsprint, I encircled the word “emptiness” and build outwards with interlocking shapes. This is the experiment design phase of my practice, so it is yet to be seen if it will become a work of art, writing, or exhibition.

When commuters once again gather at the metro station, they will join the sound of fauna and the fragrance of flora in an atmosphere of palpable connections. Perhaps we may insist on sharing that space with a revived sense of the need for a radical redistribution of resources and care.

Cities in Imagination

Cities in Imagination

David Maddox, New York

We can imagine sustainable cities—ones that can persist in energy, food, and ecological balance—that are nevertheless brittle, socially or infrastructurally, to shocks and major perturbations. That is, they are not resilient. Such cities are not truly sustainable, of course—because they will be crushed by major perturbations they’re not in it for the long term—but their lack of sustainability is for reasons beyond the usually definitions of energy and food systems. So, here’s my vision of the just city. It’s green. It’s full of nature’s benefits, accessible to all. It is resilient, and sustainable, and livable, and just.

Add a Comment

Join our conversation