While the award-winning movie Parasite (2019) by Bong Joon-ho was iconic in many ways, a terrifying scene haunts me more often than others. The scene is one where the one of the central families of the movie, the Kims, rush back to their semi-basement apartment only to discover it is flooded with sewer water. The director then engraves into our minds the still frame of Ki-jung, the daughter of the Kim family, sitting on the lid of the toilet while smoking a cigarette to stop the sewage from backflowing into their apartment. What bothers me most is that this seemingly ridiculous scene is likely going to be the reality for thousands come 2030.

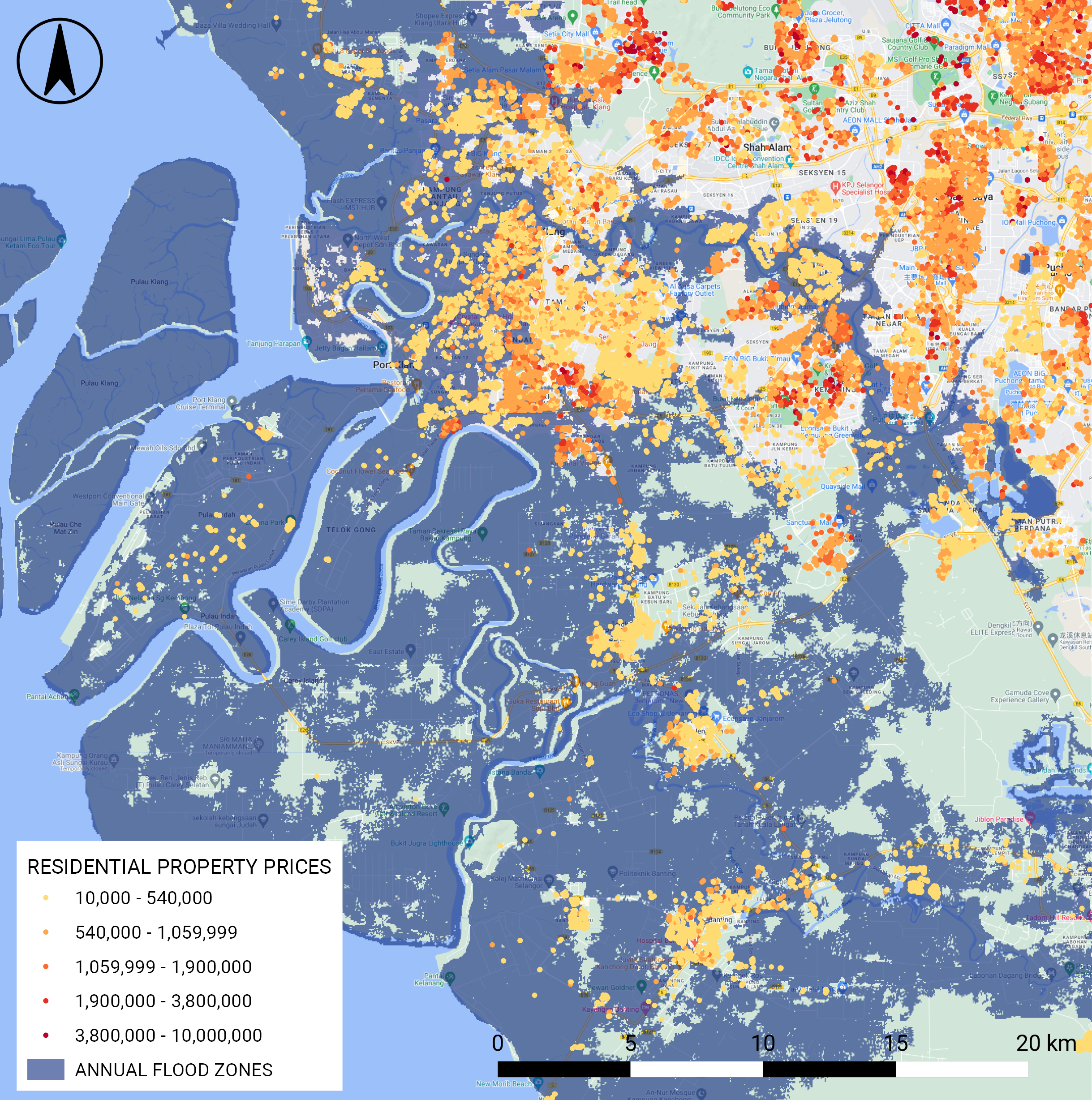

In the past few months, while diving into our work on climate risk issues in Malaysia, we found some uncomfortable data points that could turn the fiction of Parasite into reality. Greater Klang Valley, the city we do most work in, is slated to be impacted by sea level rise. By 2030, the models by Climate Central Organisation show that areas as far as 30 km inland from the coast will be at risk of annual floods (Figure 1).

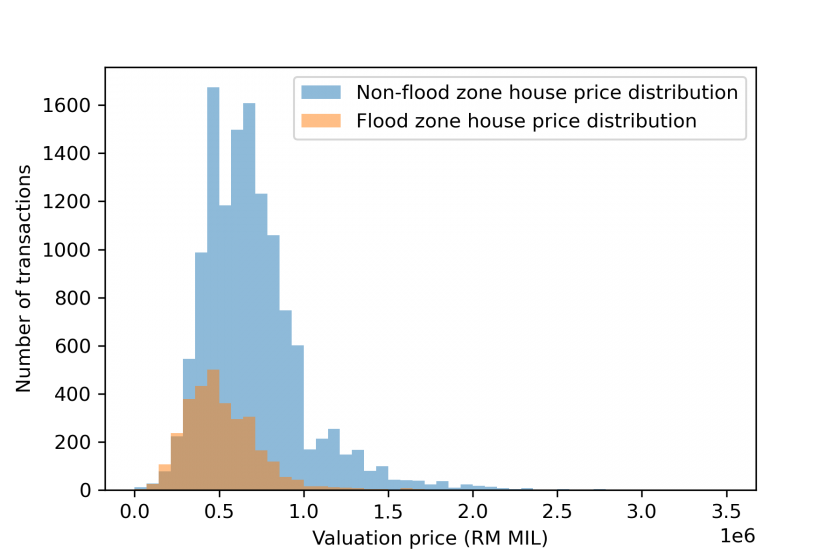

Greater Klang Valley is a city formed along the Klang River. As sea level rises in the next 8 years, the areas that will be flooded also happen to be the locations that house the oldest neighbourhoods and population, as they are often also built closest to the river. More devastatingly, our data shows that the floods will disproportionately impact the lower income groups in their relatively affordable homes (Figure 2). Our conservative count shows a minimum of 8,000 families to be affected by sea level rise in Klang alone. While we worry about the elderly population in these locations, we also lose sleep over the young middle class who might be burdened with a 30-year mortgage on top of rising inflation. Are the floods going to send them spiraling into debt and poverty?

How real are these models?

When presented with a less than ideal outcome, stakeholders often argue the veracity of the model. After all, weather forecasting is only accurate up to 5 days forward, 90% of the time. The confusion comes from the fact that these annual flood models don’t predict rainfall, the wind, or the temperature. It predicts how high the sea levels will rise and depending on where you are, will you be above or underwater.

While we debate the veracity of these models, if and when it would flood our neighbourhoods, keep in mind that most scientists believe that our sea level rise models underestimate the flooding problem we face. In the Climate Central models, only the low elevation areas would be at risk, albeit with the rising tides from the river. The model does not take into account the problem of rising groundwater. In a fascinating article “The Creeping Menace: Rising Groundwater”, Kendra Piere-Louis explains the risks of rising sea levels pushing groundwater up, flooding areas beyond the sea level rise models. In the same article, Professor Kristina Hill, an associate professor at University of California, Berkeley, was quoted to say that “We’ve way underestimated the flooding problem”.2

What can we do about it?

A fundamental dilemma of Climate Tragedies in old cities is the memories and history that will undoubtedly sink with it. Folks have strong emotional attachment to their homes hence they would understandably be reluctant to leave. Even if they can be convinced to uproot, once flooded, the monetary value of these assets and its ability to act as financing collateral diminishes. Often, the affected are left without a financially feasible option to relocate.

Our institutions and leaders have a moral obligation to exercise their resources to assess the risks at hand and generate a response plan to minimize the impact to its citizens. For preventive measures, local councils and state governments should integrate climate risk assessments as part of their development assessment plans, to be prioritized along with overall environment impact assessments and traffic impact assessments. This is to mitigate the heavy costs of relocation and post-disaster reliefs.

Recently, cities such as New York and Sydney are considering government buyouts of flood-prone homes. However, this process is often legally painful and expensive, making it difficult for emerging economies to consider. For governments who can’t afford a buyout, options under consideration include flooding and damages insurance that could cushion Climate Change impacts. Nonetheless, there is great urgency in innovative thinking on this subject to begin to build a safety net for these folks.

As millions and billions are being spent on Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) innovation investments, my thoughts are swimming toward not letting our weakest drown in the coming floods.

Cha-Ly Koh

Kuala Lumpur

Notes:

- Sea level rise during high tide by 2030 is modelled by Climate Central based on the IPCC’s AR6 Leading Consensus (IPCC 2021) model and Climate Central’s proprietary CoastalDEM land elevation model. The model assumes global emissions of heat-trapping pollution continue to rise at current trajectory with 95th percentile sensitivity.

- 13 December 2021, “The Creeping Menace: Rising Ground Water”, MIT Technology Review, Kendra Pierre-Louis

Excellent article Chay-Ly. Thank you. Especially for highlighting sea level rise pushing up/ our groundwater. This is an area that has not been studied well or studies are not easily available and it is a topic that needs to be highlighted to water resource management authorities.