Spiders are among my favorite urban neighbors. They’re flashy, charismatic, and they’re everywhere. Spiders also evoke a range of emotions and thoughts from their human cohabitants. If you see one in your house do you squish it? Do you capture it gently and relocate it? Do you run away screaming? Do you get excited and acquainted with one another?

One week in 2020 I was making coffee early in the morning and noticed a small little spider on the wall of the kitchen next to me. I thought it was pretty cool looking but didn’t think much of it and went on with my day. The next morning, I came down, and there it was again! I watched in interest as it hopped around and stared at me. And then the next morning it was back. That’s when I took a photo and later discovered through iNaturalist that it was Adanson’s house jumper (Hasarius adansoni). It stayed around for a few more days, watching me make coffee. And then it disappeared.

Interestingly, today a paper came out showing that spiders exhibit patterns of REM sleep… spiders dream! I now wonder if my companion had a particularly rough week of sleepless nights and joined me early after sunrise also badly wanting some caffeine.

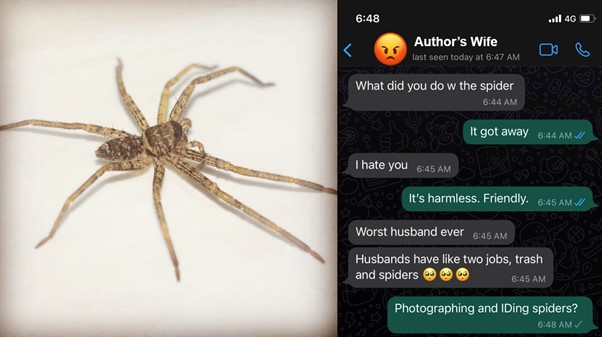

This week I’ve enjoyed a rather large huntsman spider in the shower. When I turned the water on the spider ran around and I figured it was a goner. But I should not have underestimated the spider. It too stuck around for a few days… and my wife was not happy about it, nor the fact that I refused to move it.

Indoor diversity of urban spiders

There are a number of fun studies that have examined the question of indoor spider diversity in more detail. Entomologists “raided” 50 homes in North Carolina in 2012 and collected all the arthropods they could. Spiders made up about 20% of the arthropod fauna in the homes on average and they found all sorts of spider types including funnel weavers, ghost spiders (scary), orb weavers, sac spiders, ground spiders, dwarf spiders, wolf spiders, wall spiders, goblin spiders, cellar spiders, jumping spiders, spitting spiders, cobweb spiders, and crab spiders.

Other than entertaining (or frightening) their human cohabitants, what are the spiders doing? While drinking my coffee and watching my friendly H. adansoni I liked to thank them for keeping mosquito populations low. But do they actually do this? Researchers have tested this in salticid spiders (related to H. adansoni in fact) in arenas with mosquitoes and found that spiders can consume between 2 to 9 mosquitoes a day! Female spiders also fed on a greater number than males.

In truth, there is a lot we don’t know about spiders and biodiversity in our homes. But there is increasing interest in indoor biodiversity and ecosystem function relationships. I’m willing to bet that spiders are key to a lot of indoor food webs.

Urbanization impacts on spider diversity

We know a lot more about how urbanization generally affects spider communities outdoors. Interestingly, in a meta-analysis of lots of arthropod studies across urbanization gradients, spiders were the only taxa that were not clearly and negatively affected by urbanization. This is likely a consequence of habitat- and species-specific responses in spiders that lead to either negative or positive effects on spider diversity.

For example, in Córdoba, Argentina, researchers found that spider diversity was lower in urban sites relative to both suburban and exurban (non-urban) sites. On the other hand, for ground-dwelling spiders in Hungary, diversity tends to be higher in urban areas relative to rural and suburban sites. In Sydney, spider diversity was highest in remnant habitat patches but gardens were also quite high in diversity. So, patterns of spider diversity across urban gradients are rather complex.

Has urbanization caused any extinctions of spiders? This question is surprisingly difficult to answer for most arthropods. After all, if a species isn’t in a city how do you know whether it has become extinct or was simply never there? For one case, scientists have found evidence that the trapdoor spider Apomastus has become extirpated in parts of the Los Angeles basin, leading to reduced genetic diversity.

Despite the uncertainties and questions regarding urbanization effects on spiders, experts agree that urbanization is among the greatest threats to spider conservation along with agriculture, climate change, and pollution.

Behavior of urban spiders

Porchy (Nephila pilipes) was a golden orb weaver spider that lived on my porch in 2017. She grew to be quite large, about the size of an orange from foot tip to foot tip. For months my wife and I watched daily as she would munch on flies, moths, and other creatures that would come into her web. Sometimes I would forget about her presence and ruin her web in the morning. No matter, she would rebuild it quite quickly and soon get back to work. N. pilipes are particularly feared in Hong Kong by morning runners and hikers as their webs are frequently run into and the image of an orange-sized spider close-by is not comforting to some. But they’re mostly harmless. [They will catch the occasional bat or bird though!]

Anecdotally, it sure appeared that Porchy was leveraging our strong porch light to catch insects attracted to the bulb. The web was often positioned to exploit the light (or so it seemed) and she had good success during her time on the porch. And indeed, there are studies showing that spiders are attracted to light on buildings. But the story is not as simple as it might seem…

Minnie Yuen was an undergraduate in my lab in 2016 whose passion for golden orb weaver spiders led her to conduct an experiment. She went to several sites in Hong Kong, found spiders, and then did an experiment where she set up a light at several webs and compared to unlit webs. She then put up video cameras at the webs to see how effective they were in catching insect prey/moths. We were expecting to find that the spiders next to lights would catch more prey. And then, we found the opposite! Fewer prey were intercepted in the spiders’ webs… but there were roughly equal numbers of moths that approached the web. We suspect that the light may have given moths an opportunity to detect the webs and avoid capture.

The closely related Nephila plumipes in Sydney can also thrive in urban areas. Spiders in urban areas with greater impervious area persist longer than other spiders, perhaps due to localized warming increasing survival. The species is well adapted to the urban environment and seems to be one of the “winners” of such landscape change.

In Belgium, orb weaver spiders exhibit intriguing changes in their webs with increasing urbanization. While prey capture rates are similar between high, medium, and low levels of urbanization, the architecture of the webs change significantly. Urban webs tend to be situated higher and are less inclined.

Fuzzy friends! Obviously…

Both inside your urban, suburban or rural home, you are likely to find some very cool spiders. Like us, they are going through their day trying their best to bring home the bacon. They sleep and dream. They’re just trying to make it in this big crazy world. The least we could do is not make it harder for them and fear their presence. But we should go well beyond the simple act of empathy for our fellow urban cohabitants. More attention and effort should be paid to conserving these important and unique animals. For all the Porchys out there, I hope we can create hospitable landscapes where humanity and spiderdom live together harmoniously.

Timothy C. Bonebrake

Hong Kong

Loved this article and Timothy’s reflections. as a conservation biologist it’s always an uphill battle to get the public to become enamored with the creepies and crawlies of the world, which makes conservation for them a challenge. But as the author notes, spiders are essential and important. Not to mention beautiful and complex and deserve a lot better from our species.