I spent the last few years working on and off on a book that I tentatively titled Who Was That Major Deegan Anyway? That title reflected the book’s origin story. My husband Allen and I used to get stuck in traffic on the Major Deegan every time we tried to visit my parents in Pennsylvania.

I would grumble (ok, curse) and ask, “who was that Major Deegan anyway.” Finally sick of my whining, Allen said “why don’t you find out.” Out of that casual challenge, a hobby was born—finding out about the lives behind the names that adorned so much infrastructure in New York City. Major Deegan was first, but I soon became hooked on this whimsical pathway into the history of the City I love.

One thing led to another, and I became a local world’s expert on New York City’s named roads, bridges, and institutions. People would ask me questions, and before I could stop myself, I would be giving mini-lectures on New York history. Nobody likes a know-it-all, so I learned to focus on the soundbites. Did you know that the Outerbridge Crossing was named after a person named Outerbridge? That the New York Times called Van Wyck “the most corrupt mayor in New York City history“? That the Holland Tunnel was named after its Chief Engineer? That Gracie was business partners with Alexander Hamilton? That Peter Cooper invented Jell-O? There are fascinating life stories behind each one of the names that have become New York City’s urban short-hand for traffic jams, culture, and recreation.

I started this book in 2014 after Allen suffered a catastrophic cardiac arrest. He was in the hospital for 6+ months, with the first month in a coma hanging between life and death. I had no emotional energy for my usual environmental scholarship, but desperately needed a project to keep me mentally engaged as I sat by his bedside. Working on this book was a way to connect with our past as I waited to see if he would recover. That story has multiple happy endings. Although he has limitations, he made a truly miraculous recovery and is even able to compose again. And. . . I wrote a book.

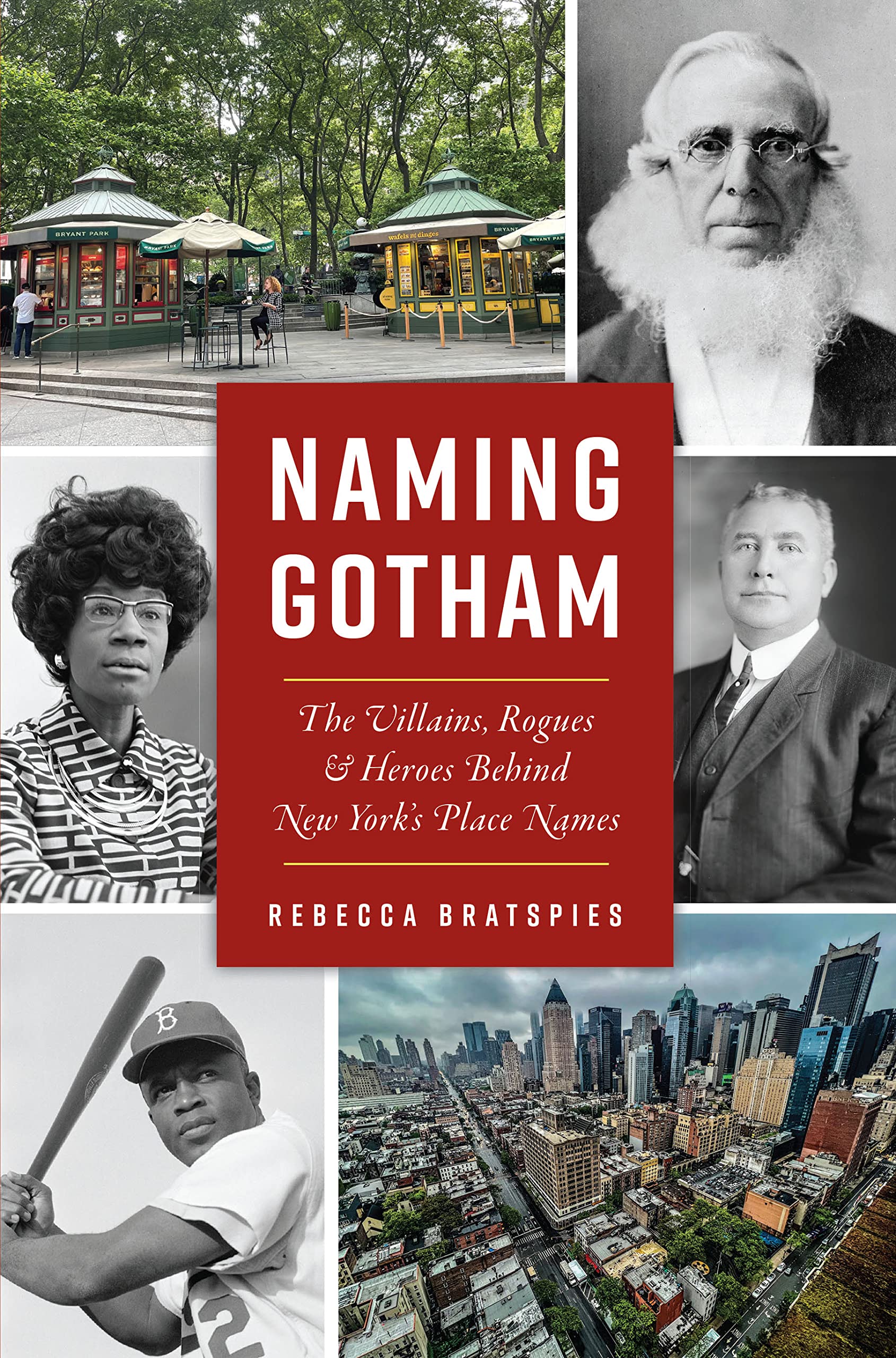

When I signed with History Press, they accepted my manuscript but rejected my title. My editor pointed out that everyone would think it was a biography of Major Deegan, rather than a book about how and why we name infrastructure in New York City. Fair point. So, we settled on Naming Gotham: The Villains, Rogues, and Heroes Behind New York Place Names.

I was having a hard time starting this blog post. Since the academy is all in a tizzy about AI, I asked ChatGPT to write an essay about the sustainability lessons from how we name infrastructure in New York City after famous people. Here is how the AI post began:

“New York City is one of the most iconic cities in the world, and as such, its streets, monuments, and landmarks have been given names that reflect its history, culture, and values. From the Statue of Liberty to the Empire State Building, the names of many of New York City’s most famous places commemorate the individuals and events that have shaped the city’s history.”

Not a bad start. Sort of. If you ignore that, unlike so much of New York City’s infrastructure, the Statue of Liberty and the Empire State Building are not actually named after individuals or events.

Rather than relying on technology, I preferred to rely on my network of friends and colleagues.

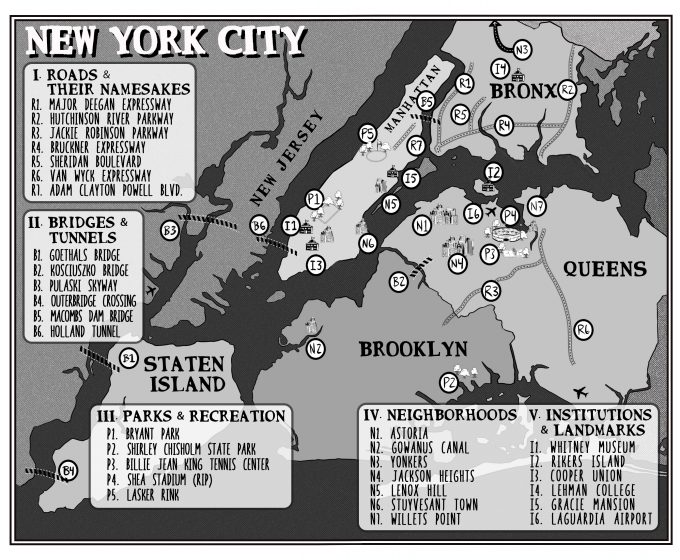

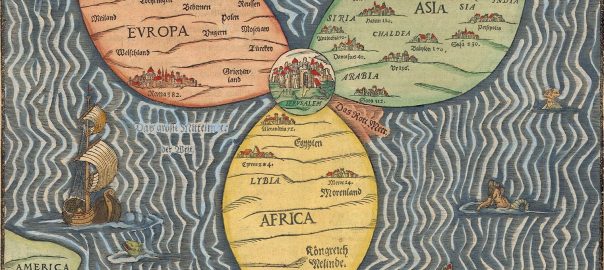

My friend and Environmental Justice Chronicles collaborator Charlie LaGreca-Velasco produced the map that serves as the frontispiece of the book and did it on very short notice.

His brother, author and artist Jeff LaGreca made the book’s fantastically silly trailer.

Environmental reporter Andy Revkin and environmental educator Lisa Mechaley graciously consented to be among the book’s earliest readers. For a book blurb, Andy wrote:

“In the rush of daily life, we tend to traverse our communities with little awareness of the visions, struggles and travails of those who shaped vital structures or whose lives are memorialized in their names. For the world’s greatest metropolis, Rebecca Bratspies has helped fill that awareness gap by crafting an illuminating guide to the people behind New York City’s transportation, recreational and institutional landmarks.”

He and Lisa shared that they “always joke ruefully about how many parkways are named for the things they ruin.” Their examples—the Hutchinson River Parkway and the Sawmill River Parkway—both of which cut off community access to the rivers. Moreover, the salting of these roads, not to mention the traffic they create, contributes significantly to air and water pollution that drives a host of health impacts in the surrounding community.

Aside from the fact that my friends are far more talented and insightful than any AI could ever dream of becoming, this project taught me two important lessons about urban sustainability.

First, that no amount of road construction will ever solve the problems of congestion. The justifications for the Holland Tunnel, the Goethals Bridge, and the Pulaski Skyway in the 1920s, and for the Van Wyck in the 1950s was to alleviate congestion from automobiles. These names are now synonymous with congestion. This lesson is critical as we consider the role of public transportation, and ongoing proposals to expand the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway and the New Jersey Turnpike leading to the Holland Tunnel―you guessed it, to alleviate congestion. Initiatives to reduce private automobile travel through congestion pricing are far more likely to succeed. After years of wrangling, New York finally seems poised to implement congestion pricing for parts of Manhattan. And, of course, the best way to reduce congestion is to invest in more and better mass transit and to continue to build the protected bike lanes that have proven immensely popular.

Second, profound economic transformation is possible. It was educational (read: shocking) to discover just how much New York infrastructure is named for those who participated in and profited from the slave economy. From its earliest days as New Netherlands, until it was finally made illegal in 1827, slavery was “part and parcel” of New York’s economic organization. Among those I write about in Naming Gotham, Alexander Macomb enslaved 12 Black persons, the Rikers family enslaved at least 10, and Lennox enslaved 4. Even after the formal end of slavery in New York, trade in goods that were made by enslaved persons continued to enrich a generation of New Yorkers. The names of these enslavers are familiar, even if their association with slavery is not. There is still tremendous work to do to acknowledge that history, and to grapple with what these names mean going forward. Yet, there is an additional lesson to learn. The visionary campaigners who fought against the evils of slavery were often derided as impractical dreamers who were unable to face economic facts. Nevertheless, they persisted. And they won. It was a long, hard, and bloody struggle, one that faced resistance every step of the way from those whose fortunes rested on the enslavement of others. But we ended the economy that put enslaved labor at its core. This gives me hope that we can do the same for the economy built on fossil fuels.

Imagine what New York City will look like if we learn both lessons at once. We can eliminate our dependence on congestion-creating private vehicles while we simultaneously replace fossil fuels. We can have city streets that are safe for pedestrians and bicyclists, with rapid, non-polluting mass transit. Not only can we do this, we must! The IPPCC’s latest report makes that abundantly clear. What then of New York City’s network of roads, bridges, and tunnels that all have congestion as their rationale? And most importantly, what will we name our new, more sustainable infrastructure?

Rebecca Bratspies

New York City

nice. Love the photos. thank you for sharing.

City Island – A Slice of NYC Paradise https://cimages.me/content/new-york-lighthouses