about the writer

Martha Fajardo

Martha Cecilia Fajardo, CEO of Grupo Verde, and her partner and husband Noboru Kawashima, have planned, designed and implemented sound and innovative landscape architecture and city planning projects that enhance the relationship between people, the landscape, and the environment.

Martha Fajardo

The landscape, the place we live in, is our most important life support. Population increase is pushing the limits of the land to a critical point of rupture. The complexities of the current issues, the impact of rapid urbanization; the management of resources; the after-effects of disasters, both natural and manmade. Soil is being made less fertile; water is drying up; trees are being felled; animals and people are being made less viable. Inequity and poverty thrive while the land is put into a state of alienation. Here lies the land of possibility; a biophysical territory to be nurtured with well-informed anticipation and evaluation; a transforming landscape approached thorough impact assessment, visionary planning, and sensitive management.

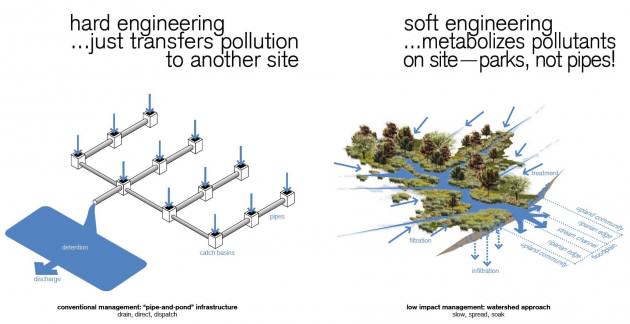

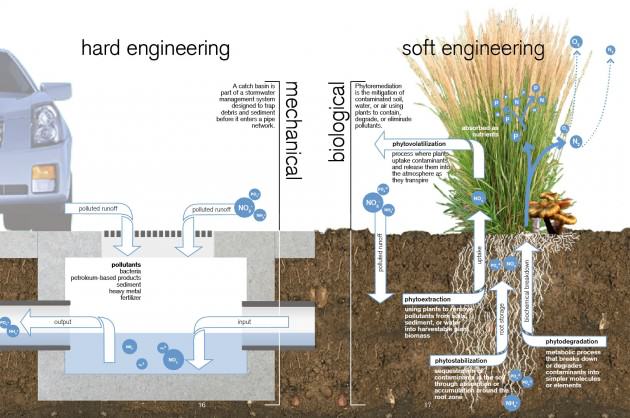

Collaborative processes demand experienced professionals, teams, and leaders that stand for for analysis, planning and/or design. Therefore, programs must require the application of landscape ecology and conservation biology principles to the strategic design of urban infrastructure; training for ways to structure and guide the flows of organisms, materials, and energy that pass through a city in ways that support the characteristic biodiversity of a region. Here, the fundamentals of ecology embrace the integration of landscape issues: disturbance, fragmentation, landscape manipulation, fundamental ecological processes, composition and structure, and environmental influences.

Landscapes positively contribute to the complexities of the contemporary city, to a more equitable distribution of ecological and environmental resources, and to the creation of better futures across all regions of the world. Landscape architecture, as a very ancient discipline and practice, carries ecological knowledge of generation after generation and has demonstrated a significant capacity to react and to adapt.

The habitat professions’ programs need to understand the basic principles and processes of city as a system. Happily, landscape architecture and allied design disciplines and practices are nowadays developing better capacity to facilitate dynamic adaptive processes; contributing to a transition from a first to a second phase of ecological design.

about the writer

Barbara Deutsch

Barbara Deutsch is the Executive Director of the Landscape Architecture Foundation, and has diverse experience from the for-profit and nonprofit sectors.

Barbara Deutsch

Absolutely!

By definition landscape architects design for natural processes, natural resources, and people so a thorough understanding of ecological sciences is essential.

Now more than ever, clients and government agencies have specified interests in sustainability. All professionals contributing to sustainable design projects should have an understanding of the importance of ecology and its basic principles to achieve optimal results. An understanding of natural processes, such as the hydrologic cycle in an urban context, is also critical to designing, building, and maintaining high-quality urban ecosystems.

Landscape architects understand the city as a system and are well-positioned to “translate” — or facilitate a greater understanding of ecology among a full design team by integrating and applying the sciences with the design process. Landscape architects should also have enough knowledge of ecology to “know what they don’t know,” and know when to engage a botanist, soil scientist, ecologist or other specialist.

Beyond designing for ecological processes, landscape architects and others must be prepared to communicate these concepts and goals to clients, agencies, and municipalities: those who will commission or incentivize exemplary sustainable design projects. The Landscape Architecture Foundation is helping practitioners make the case for more sustainable design through its Landscape Performance Series, an online interactive set of resources to show value and provide tools for designers, agencies, and advocates to evaluate performance and make the case for sustainable landscape solutions.

Urban Ecological Design was the central focus of my studies at the University of Washington’s Department of Landscape Architecture. Though ecology is not specified per se in the landscape architecture accreditation standards, natural systems, the principles of sustainability, and ecosystems are all key components of landscape architecture programs and central to students’ knowledge and values. Tools such as the Landscape Performance Series, as well as SITES, can augment the curriculum requirements to help practitioners both design for ecological function and understand and promote the ecological benefits of their work.

about the writer

Norbert Mueller

Norbert Müller is vegetation ecologist and Professor in Landscape Management and Restoration Ecology at the University Applied Sciences Erfurt, Germany. His main fields in research and lecturing are conservation biology, urban biodiversity and sustainable design. Since 2008 he is president of URBIO (http://www.fh-erfurt.de/urbio).

Norbert Müeller

The main challenges for life on Earth for this century are urban population growth, climate change, and loss of biodiversity. Urban landscapes are using 75% of the global resources, are producing 80% of the greenhouse gas emissions, and are the main drivers of biodiversity loss. For the future, it will be essential to reduce the urban ecological footprint and make our towns and cities more sustainable. The main responsible planning disciplines to meet these challenges are architecture, urban design, landscape architecture, and urban planning.

Therefore, it is important for professionals working in these disciplines to have a certain minimum level of learning about the fundamentals of ecology. Today, many programs at schools and universities offer courses in ecology and their specifications — especially plant, vegetation, and animal ecology, as well as climatology, hydrology, and soil ecology. Also, urban ecology, the ecological discipline that examines the interactions between the abiotic and biotic environment in urban areas, is more and more included in programs. Although there is a growing concern about sustainable urban design, there are still major backlogs both in theory and in application — for example, even now we do not have standardized tools for designing sustainable urban green spaces. Therefore, future research and education must focus not only on the fundamentals of ecology but also on design methods how to apply ecology for more sustainable urban design and planning.

A recently opened online survey by the network URBIO on knowledge gaps and research priorities for urban planners and urban stakeholders stated the following 5 questions as most important:

- What are the ecosystem services offered by a particular landscape?

- How can ecosystems in a given city mitigate the vulnerability of cities in time of climate change or after natural hazards?

- What is the social and economic value of conserving biodiversity and ecosystems?

- How can we integrate ecological design and tools into strategies for land use planning and management?

- How to set up a strategic policy to integrate biodiversity in the city?

I want to invite all readers of this blog to participate at this online survey to find out further knowledge gaps in the understanding of cities and how to design them more sustainable.

about the writer

Kaveh

Kaveh Samiei is an architect and researcher in built environment sustainability.

Kaveh Samiei

Applied disciplines such as architecture, landscape architecture, and urban design, are all interdisciplinary fields that we categorize as environmental design disciplines. An architect works as a connector of different fields such as design, art, engineering, environment, psychology, and so on. Thus, yes! Architecture, as one of the main disciplines of the built environment, requires a minimum level of learning about ecology and the environment. In fact, every construction imposes itself onto nature and alters the ecological systems and function; nature works as an integrated whole. On the other hand, designing urban landscapes and ecological planning without considering the role of architectural design and building blocks is an abortive attempt! Although landscape architecture and urban design students may take courses in “Plant ecology” and “Urban ecology”, landscape architecture is a new field in Architecture and Urban Planning schools in Iran, and students can enter this program only in the graduate levels. “Climatic design” and “Human, nature and architecture” are the only courses that architecture students in Iran currently must take at the undergraduate level!

Therefore, three years ago, I began to teach “Ecological architecture” in “ARCH V”, a final design studio for undergraduate architecture students at the University of Semnan, School of Architecture and Urban Planning. I found out that we have to introduce fundamentals of ecology and sustainability before entering key subjects of design; some students can’t understand why we require discussion of sustainable design! “Theoretical foundations of architecture” was a free content course in which teachers typically spoke about different and diverse subjects; later, I decided to utilize this course for teaching “Fundamentals of ecology” and in the following semesters, students could apply their comprehension of ecology in designing ecological residential buildings. Probably I taught that course to architecture students for first time in Iran!

There were some cultural and logical problems too that emerge from misunderstandings about the relationship of humans and nature — core viewpoints that have traditional and modern roots of human dominance on nature and resources as materials for consumption! So without shifting minds, we can’t go ahead. After three times teaching these courses, many students, even some students in year two and three, became interested and curious in ecological and sustainability issues! Now, under my supervision, six students are studying ecological approaches to design through their final thesis. Also, in collaboration with my students, I’m working on new methods of learning ecological design by doing a comprehensive research project about architecture education with an emphasis on sustainable, ecological design; I hope we can disseminate the results in the near future.

about the writer

Paul Downton

Artist, writer, ‘ecocity pioneer’. A former architect with a PhD in environmental studies, Paul is distressed by how the powerful idea of ecological cities has been perverted, citing ’Neom’ as a prime example. Still inspired by his deceased life-partner Chérie Hoyle (1946-2024), Paul is continuing his graphic novel / epic poem / art project called ’The Quest for Wild Cities’ that he promised Chérie he’d finish along with his 80% complete ‘Fractal Handbook for Urban Evolutionaries’!

Paul Downton

Ecology is about the relationship of organisms with each other and with their environment, so all those that design and manipulate the environment should have a minimum level of learning about the fundamentals of ecology. Buildings and cities are constructed ecosystems even if they’re not designed as such.

They need to be designed as such, yet architecture’s most influential culture heroes have betrayed open antagonism to nature. In 1925, arch-Modernist guru Le Corbusier praised cities as an assault on nature. In 1986, I heard an imperious Zaha Hadid confess hatred of nature in a conference keynote. For all his stylistic skills, like most of his profession Richard Gehry is unlikely to be remembered as a champion of green design.

Urban design and planning is about creating urban environments in which coherent relationships exist between its elements, yet I have seen city planners reduce that idea to an insistence that buildings share the same eaves heights in the name of ‘contextualism’. The destructive impact of our built environment is exacerbated by ignorance of how its impacts come about, and that ignorance runs deep, especially in architecture and urban design. It is vital to regard the built environment in terms of process and place rather than objects in space and it makes no sense to place the care of living systems in the hands of people who don’t have a basic understanding of natural processes, yet in the world of design the power of the image trumps reality and facilitates a kind of environmental double-think in which the word ’sustainable’ is routinely applied to projects that are ecological nonsense.

All programs related to the built environment need to contain a minimal level of familiarity with the fundamentals and language of ecology to ensure such nonsense does not continue.

about the writer

Noboru Kawashima

Noboru Kawashima is a Japanese biologist, urbanist and landscape architect, living in Colombia as Grupo Verde Ltda Vice-president.

Noboru Kawashima”

Our human lives are dependent on productions from natural resources: food, energy, industrial goods, construction, and everything.

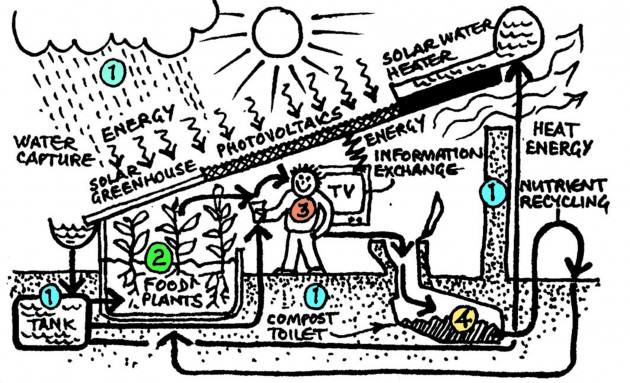

The natural resources are treated in cycles of extraction from the earth, transportation, processing, trading, consumption, and going back to the earth. For example, food: cultivation from the fertility of the earth, transportation to market and trading, cooking, eating, and the organic materials go back to the earth. These cycles are very complicated and cross each other, and with many other cycles such as energy cycles, industrial cycles, commercial cycles, social cycles, and so on.

Many times these cycles are not complete, at least in a short term, or are interrupted. There are environmental costs when the cycle is not closed, such as when there is no re-cycling and no sustainability in the use of renewable natural resources. For example, a sewage system is very good to sustain sanitary conditions in urban areas, but the organic materials do not come back to the earth of cultivation, and so there is the interruption of the cycle.

It is estimated that the percentage of world urban population will rise up to 80% in 20 years. The difficulty is that urban areas are far from the places of extraction of natural resources: far from cultivation fields, far from waters of fishing industry, far from mining sites, far from oil wells, far from water power plants, and so on. So, the most of urban inhabitants, day by day, will have less chance to recognize how their lives are dependent on the natural resources and less chance to know the importance of establishing and sustaining cycles of renewable natural resources.

Landscape Architecture is work of creating artificial nature. It is a man-made environment. But we cannot aim too low in landscape architecture just because it is not “real” nature. You can see in a green area the living things growing, flowering, fruiting, and dying. You can touch the soil in a garden. In this way you will feel in your daily life the importance of soil, and recognize our dependence on natural resources.

From the view-point of natural resources the duty of architecture, urban design, landscape architecture, and urban planning programs is to:

• Create urban environments that minimize the interruption of cycles of natural resources.

• Create urban environments so that inhabitants may recognize their inter-dependence on natural resources and the importance of sustainability of the cycles of natural resources.

In these senses, architecture, urban design, landscape architecture, and urban planning programs must require a certain minimum level — or more — of learning about the fundamentals of ecology.

Leave a Reply