Rightly, people recently have been valuing Indigenous cultures and writing about them. Not wishing to mimic or appropriate, but as an attempt to learn from such ways of thinking, this essay uses a form of circular storying[1] that becomes nonlinear. I stumbled upon ‘storying’ (the making and telling of stories) through my practice as an ecological artist/researcher while working with a youth drama group in 2017. We were working towards a theatrical contribution to a forthcoming lantern parade in Cockermouth, northwest England, to celebrate the anniversary of floods that had devastated the town in 2009 and 2015 and I introduced the idea of a fictional fish. From that idea, the group created an elaborate archetypical, right-of-passage, myth that they performed as a giant shadow puppet-play across the River Derwent. I later realized that several of my projects had initiated what I had rationalized as ‘dialogues’ with people, non-humans, places, and time. I then discovered similarities to Indigenous or ‘otherwise’ ways of thinking, through the work of Vanessa Andreotti[2]. The reason for this explanation is that this text weaves together several ideas, themes, and events that I hope, for the reader, flow to make some kind of sense.

The main story is written from one perspective, about a series of six talks with groups of people in a place in early Spring 2023. But this first requires context about the place; Barrow-in-Furness, Cumbria, Northwest England (aka Barrow).

A Place in Context

The last Ice Age left the Furness Peninsular, on the coast of northwest England, geographically remote; defined by the River Duddon Estuary to the north, Morecambe Bay to the south, and the Irish Sea to the west. For much of its history, it remained predominantly impenetrable to the east, with densely forested mountains, lakes, and wild animals. A few Celts settled to mine copper, iron, and coal and they cultivated some of the low-lying land for arable and cattle farming. The Romans were not particularly interested in this place, so the Celts were followed by Vikings who settled and gave their names to many of the villages in the area. Then the Normans arrived and in just over half a century, Cistercian Monks founded Furness Abbey in 1123. By the time of Henry VIII’s dissolution in 1537, Furness Abbey was the second richest in Britain, with iron smelting, agriculture, and fisheries. However, Barrow itself remained a small fishing hamlet of only 32 dwellings (including 2 pubs) until 1843.

Boom Town

In 1839, iron prospector Henry Schneider arrived and by 1846 he opened Furness Railway, providing the means of distributing iron ore, slate, and hematite. Schneider was joined by James Ramsden, the railway’s general manager and he established blast furnaces to turn the iron into steel. By 1876, having received substantial investment from William Cavendish, 7th Duke of Devonshire and the Duke of Buccleuch, the Port of Barrow facilitated the export of steel from what had become the largest steelworks in the world. The port developments had, in the meantime, prompted Ramsden to found the Barrow Shipbuilding Company (1871) with merchant ships giving way to orders from the Royal Navy to expand and protect Britain’s burgeoning Empire. Following Ramsden’s death in 1896 the shipyard was taken over by Vickers Ship Building and Engineering, adding their capability for manufacturing armaments for the army and navy. Warships were also built for export, including Japan’s flagship, the Mikasa, in 1905. ‘The Yard’ continued to build aircraft carriers, passenger liners, and airships, and in 1901, it launched its first submarine. By 1914 it had built the largest submarine fleet in the world for the Royal Navy.

‘The Last Place God Made’[3]

At this point, it’s worth considering the demographic and cultural changes that took place from 1839 to 1939. As previously stated, the population of Barrow and surrounding villages prior to 1843 was less than 3,000. By 1876 inward economic migration from Cornwall, Ireland, Scotland and other parts of Lancashire increased the population to over 19,000, with a sizable Indian community and some from China.

As well as being the Furness Railway general manager (the ‘Fat Controller’ in the Thomas the Tank Engine[4] books) and four-times Mayor of Barrow, James Ramsden was keen to express the town’s success by embracing the philanthropic ideas of the age. Barrow became one of the first British towns to be ‘planned’. Influenced by the altruism of Lever Brothers’ Port Sunlight (1888) and Cadbury’s Bournville (1893), Vickerstown (1898-1905) was developed as a ‘model village’, on Walney Island, adjacent to the shipyard. Before he died in 1896, Ramsden’s planning included a grid of well-constructed terraced housing in the town center with a tree-lined avenue leading to a central square. A grand neo-Gothic Town Hall was constructed (1885-1889) from local red sandstone and slate. These gestures of civic grandeur and benevolence continued as the population rose to over 60,000. Nicknamed ‘the English Chicago’ for this rapid growth, the town kept growing as the industries expanded, and in 1905 it was referred to as, ‘the last place God made’, at the zenith of Britain’s Industrial Revolution and colonial Empire.

As Fortunes Come and Go, so do People

During the First World War (1914-1918), with the increase in munitions workers, the population surged again to 82,000. During the Second World War (1939-1945), Barrow was targeted by intense air raids that mostly bombed civilian housing, so that people left the town at night to sleep under rural hedgerows. Following WW II, with a population of 77,900 (1951), local mines (1960), the ironworks (1963), and then the steelworks (1983) closed. As the main employer in the town, the shipyard focused on submarine production, with the first UK nuclear submarine, HMS Dreadnought launched in 1960.

In 1986, the Devonshire Dock Hall (‘The Sheds’) was constructed to develop and build the Vanguard class of nuclear-powered submarines, armed with Trident II missiles, as part of the Government’s Trident Nuclear Programme of ‘Continuous At Sea Deterrent’[5]. The Sheds overshadowed the Town Hall to become Barrow’s iconic skyline. However, in 1991 the end of the Cold War saw a drop in defense budgets, and as shipyard orders fell away VSEL’s workforce shrank from 14,500 in 1990 to 5,800 in 1995, making Furness General Hospital the largest employer in the town. The knock-on effect throughout Barrow meant that many businesses collapsed and there was a sharp rise in unemployment in this remote town, dependent on a single major employer. Despite regeneration initiatives from the Central Government and Europe to build better road access and a new shopping mall, the town’s population continued to decline to 71,900 in 2001, and 69,100 in 2011 and was projected to fall to 65,000 by 2035. In 2011 Barrow’s demographic profile was 96.9% ‘White British’ with ethnic minorities of Hong Kong Chinese, Filipino, Indian, Thai, Kosovan, and Polish people making up the 3.1%. By 2021, little had changed[6]. Barrow remained the largest shipyard in the UK, with BAE Systems employing 9,500, a third of the town’s workforce.

Educating the Future

BAE Systems had taken over the shipyard in 1999 from Marconi (VSEL) and in 2016 the Government invested £300 million in constructing additional ‘sheds’ to facilitate the development of the Dreadnought class of nuclear submarines to replace the Vanguard class. This development again significantly changed Barrow, as thousands of contract workers flood into the town every Sunday evening and leave mid-day every Friday. While the Portland Walk shopping mall and surrounding streets see shops of all sizes close, new bars with craft beers at London prices have opened. Gyms, fast food outlets, hotels, rental apartments, and expensive cars now dominate the town’s economy. BAE Systems with the universities[7] of Lancaster and Cumbria are providing new training facilities and opportunities for schools and further education colleges to prepare their students for apprenticeships; a move that some see as a return to old paternalistic values of the ‘Yard’ as the center of the community. However, the character of the Yard has changed from one of openness and benevolence, with its own brass band to very strict high security, managed by the Ministry of Defence Police.

Other changes are taking place with Barrow Offshore Wind Farm, Ormonde Wind Farm, Walney Wind Farm, and West of Duddon Sands Wind Farm becoming the largest off-shore wind farm in the world (2006-2018). In 2022 the Government recognized Barrow’s estates of depravation through its Levelling-up[8] policy to regenerate civic infrastructure. This has been further enhanced by Arts Council England investing in Barrow through its Priority Places and Levelling-up for Culture Places strategy, with increased revenue funding for new and existing arts organisations. It also created BarrowFull (formerly Barra Culture) to promote arts, culture, and creativity in the town.

The shipyard has, this year, been awarded the AUKUS[9] contract to build nuclear submarines for the next 35 years and BAE Systems advertised for 1,200 new jobs[10]. With attractive salaries, many of these have been filled by mechanical engineers from independent local motor garages, but as an unintended consequence, many local independent motor garages have closed.

‘All the world’s a stage…’

The 19th and early 20th Century increased population of Barrow-in-Furness gave rise to the emergence of many forms of local entertainment. Blessed with stunning coastal scenery the western shoreline of Walney Island became a great attraction with an open lido and other entertainments for holidaymakers. There were many pubs and working men’s clubs for after-work socialising, with dedicated activities and hobbies from darts and dancing to brass bands and model railways, pigeon racing, and allotments to soccer and rugby. Women came into their own with competition dancing and festivals, but Barrow was essentially a man’s town.

Barrow did boast four theatres during its heydays between 1864 and the 1970s, offering Music Hall, Variety, concerts, drama, ‘animated pictures’, and cinema. The theatres changed their names as they were revamped to meet changing popular demand, and one still remains as a nightclub. In 1990 the Civic Hall (1971) was reconstructed as the Forum 28 entertainment complex. Her Majesty’s Theatre was demolished in 1972 and the proceeds of its funds contributed to the Renaissance Theatre Trust that pioneered touring arts throughout Cumbria to the mid 1990s. It, also welcomed the radical celebratory and arts company, Welfare State International[11] (WSI) to the nearby town of Ulverston where it remained until 2006.

One of WSI’s biggest projects was its eight-year urban regeneration residency in Barrow (1982-1990). The culmination of this cultural programme in 1990, was a festival of locally written and performed plays, The Shipyard Tales, and a spectacular pyrotechnic event, The Golden Submarine. The legacy of this work, however, was to create the space for the Barracudas, a nationally acclaimed carnival band[12], Furness Youth Theatre[13], and eco/visual arts company, Art Gene[14]. The youth theatre company and arts organization continued and were joined by the award-winning Signal Films & Media[15] (2007) and the sonic arts company, Full of Noises[16] (2009). Today many people continue to walk their dogs and children, fly kites, swim, windsurf, sail, and engage in many hobbies, from upholstery and ballroom dancing to model railways, choral singing, and ukulele bands. Barrow, also boasts an internationally acclaimed opera singer, contralto Jess Dandy.

Culture, in the sense of diverse human activities being passed down through the generations, has adapted to change and evolved in this industrial town. However, despite everything mentioned above, in the national press and media Barrow has gained a reputation for lacking in Art World Art and Culture, and cast as the cultural backwater. The question that emerges, therefore, is what constitutes ‘culture’ and what value is given to local culture?

‘TALK IN THE PARK’: another kind of story

About a year ago, I was invited to write a conference paper, a short article, and a book. I, also thought it would be a good idea to apply for a small grant from my local community arts organisation to create a series of talks about art, creativity, and culture.

I presented the conference paper, online, to the University of Murcia, Spain, on the topic of Generous Domains: Storying an Ecological Brave Space, to explore ideas of decolonizing the environmental sciences, based on a United Kingdom Research and Innovation (UKRI) funded research project that I led with Valeria Vargas of Manchester Metropolitan University.

The short article, Unreal Estate: A Dialogue with Pigeons, was for a TNoC Roundtable, ‘How can artists and scientists co-create regenerative projects in cities?’ As for the book, Metapoiesis: an inquiry into space, this article may become one of the chapters.

Meanwhile, I gained a small grant from the local arts development agency, BarrowFull, for a series of six, weekly, two-hour Saturday morning events. The title for the programme suggested itself – TALK IN THE PARK.

Taking time to talk

The idea for the six talks came from my experience as a fifteen-year-old attending adult education evening classes on Life Drawing, Painting, and Art History in London, in the late 1960s. The latter was led by my school’s sculpture teacher, George Poole (1915-2000), and was attended by a diverse group of about twelve people on a Friday evening. Each week, George chose a theme, projected slides of artists’ work, and started a conversation that would last around two hours. The conversations were the real element of learning, as everyone had something to say that prompted questions beyond aesthetic appreciation to include politics, cultures, sex, music, architecture, and environment. The exchanges carried on at the local pub to fuel my sense of inquiry and passion for art as integral to life, beyond galleries, museums, and concert halls. There was no question, then, of the sessions not being in-person, so social interaction was embodied in the dialogue that evolved, session upon session. We each learned to talk and share a common evolving language.

Let the talking begin…

Throughout January 2023 I distributed a thousand black and white leaflets at the Library, Dock Museum, Forum entertainment venue, arts companies, and train station. I gave interviews on local radio, emailed my networks, and posted on social media. On the first day, I brought with me tea, coffee, and a good supply of biscuits.

Here, I use the PowerPoint slides to illustrate some of the ideas and issues I raised to prompt conversation and provide some context for newcomers each week. I tried not to manage or determine people’s participation, but to facilitate and provoke engagement. On occasion, I did contribute my own views, as the view of another participant, but this dual role was at times difficult and constantly required nimble assessment of the reactions of others. In this sense, I tried to step back from being a lecturer or performer to being one of the group, within the group. The first Talk…

WEEK 1. February 11. Five people attended.

I was pleased that I was not alone and the number resembled a small dinner party. The participants were all known to me; two retired school teachers, a local civic councillor/journalist, and two artists. I introduced the concept of the series of events and only got as far as the fifth slide, when everyone had a story to contribute about pigeons, or in one case, the intricate story of fostering a crow with a broken wing for several years. The session over-ran by 30 minutes and nobody wanted to take a half-time break. They just seemed to enjoy the experience of ‘having a good talk’.

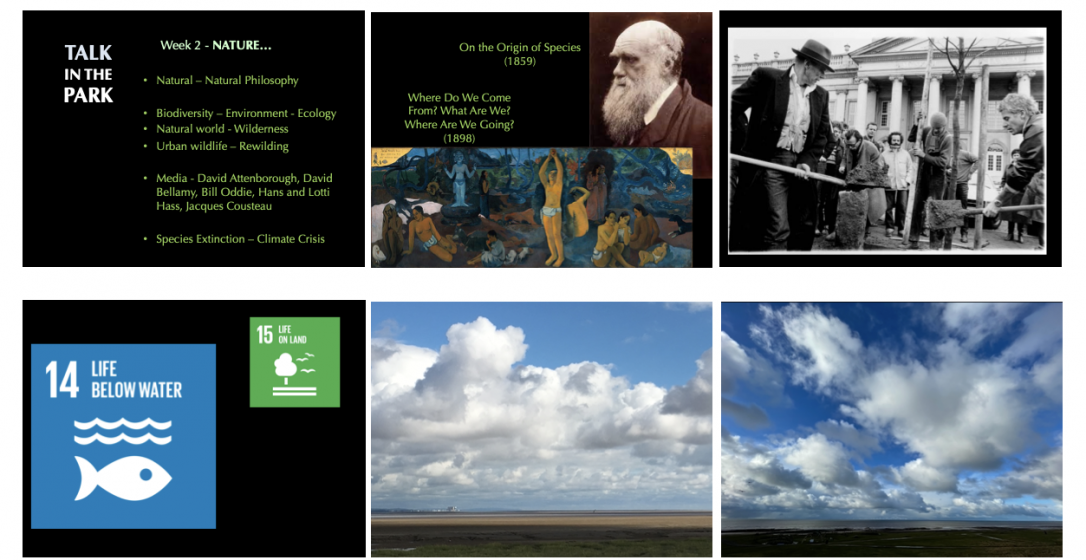

WEEK 2. February 18. Seven people attended.

An artist/academic, a poet, and a lawyer joined the previous week’s group and one of the teachers did not attend.

At the end of the first session, I asked those present what topic they would like to focus on in week 2. The consensus was our relationship with nature. This provided fruitful conversation around human exceptionalism, separability, and the need to reconnect with nature. The importance of nature-focused education was explored, as a subject developed by several of those in the group who had used the area’s coastal location in their teaching practice. A local woman remembered her childhood experiences of visiting the Irish Sea coast of Walney Island in the 1950s. Examples were given about some children from ‘deprived’ families who had not experienced their outstanding natural location and this raised issues around the relationship between culture and nature, education, knowledge, and community. The depiction of Nature through the arts and sciences provided a fruitful line of inquiry as obvious to some but as a new way of thinking for others. Eventually, the extinction of species, the climate emergency, and global political will emerged. This carried over to the following week.

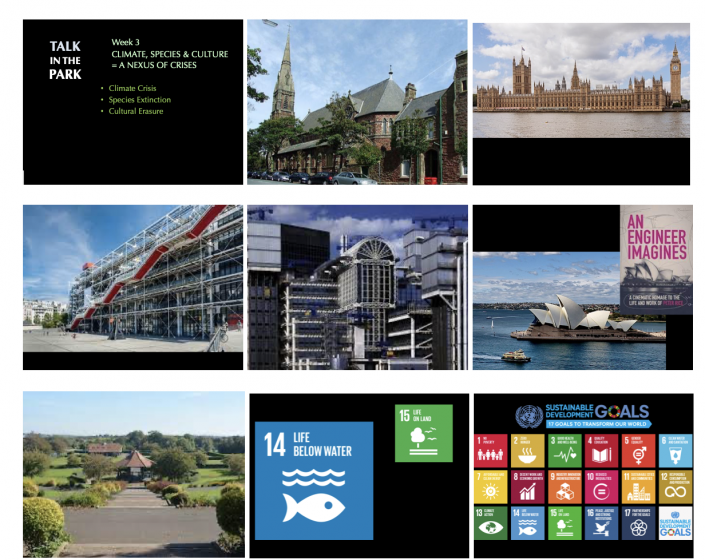

WEEK 3. February 25. Seventeen people attended.

An artist brought their two young children, grandparents, and nephew in addition to the core group.

In addition to an exploration of some of the issues surrounding our response to ‘the nexus of climate, species and cultural crises’, the conversation from the previous week had touched on very human expressions of architectural and landscape design at the heart of Barrow’s cultural identity. As a geographically isolated urban/coastal/industrial town, Barrow-in-Furness represented the conclusion of the Industrial Revolution and the British Empire. This had been expressed through fine Victorian and Edwardian buildings, including St Mary of Furness Catholic church, designed by the son of Pugin (architect of Westminster Palace). Indeed, Barrow Park was designed by Thomas Mawson, the most sought-after landscape architect of his day. These vanity constructions were further compared with contemporary architecture and urban developments. Discussion around such physical and societal development moved to the concept of ‘Sustainable Development’ and this gave way to the notion of different people’s worldviews and the potential for diverse ways of thinking, or not.

The poet brought their young niece, an urban ecologist returned to their home town and two local couples joined.

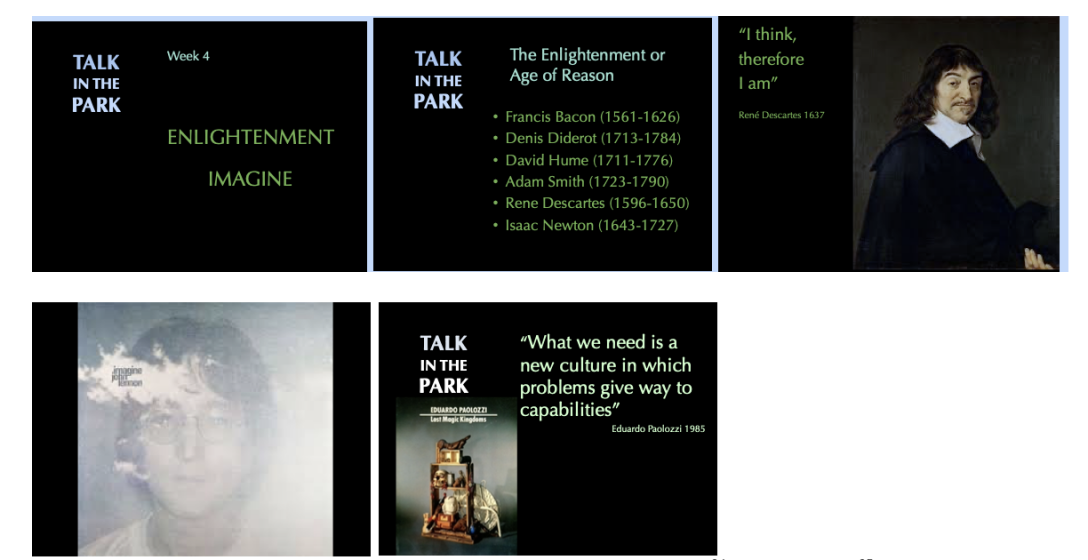

The previous week, someone had praised the Enlightenment and rational thinking as the highest value of human evolution and this was promoted by several regular members of the group, so I thought it was worth further exploration. Surprisingly, to me, nobody seemed to challenge this idea, as it was claimed that the Enlightenment, provided the foundations of Modernity, contemporary education, and the scientific method. Meanwhile, I had noted the lack of people of colour and people other than white European ethnicity among the participants, but thought that the largely educated or even cultured group would have challenged some of the precepts of the Age of Reason… and colonialism. Offering John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s ‘Imagine’ as an antidote to Rene Descartes went nowhere, but Eduardo Paolozzi’s call for ‘a new culture in which way problems give way to capabilities’ did gain some traction, although more from an engineering perspective of Problem-Based Learning!

This topic seemed to be surprisingly difficult for the people to comment on, so I offered more input than I had wished, in an attempt to provoke some response. This included the idea that different cultures experience space differently and that Western Modernity had both valued this richness and appropriated it. A paradox exemplified in visual art by Post-Impressionism’s fascination with Japanese prints and Cubism’s adoption of African sculpture; each of which enhanced Western ways of seeing, while othering the cultures from which they came.

These examples gave traction to the group and in particular, the other three men, two of whom were accomplished artists. While there was some input from the women artists, the men (including me) enthusiastically ran away with the conversation. Then, quite quietly, one of the women asked if we might collectively consider the idea of ‘space’ as having gendered aspects. The conversation paused. The men looked quizzically at each other, agreed with this idea, and carried on. Bizarrely, their conversation moved onto a critique of male football supporters and tribalism within cultures.

While I tried very hard to catch the attention of each of the women to contribute, none took the cue. Finally, out of frustration, the woman who introduced the concept of gendered space snapped and reiterated her idea as a complaint and two of the other women then agreed. Perhaps ashamed, or dumbfounded by their (our) inability to shift the conversation, the men stopped. As the meeting drew to a close, the woman who had complained intervened, with some assertiveness, to consider the place/exclusion of women in the conversation.

Getting it wrong can sometimes hurt and hurting can sometimes be necessary for a learning experience. I took some time and apologised for not facilitating well enough. As the frustrated woman is one of my closest friends, I agonised about the last session and how to manage/not manage it. Something had to be said, we couldn’t leave the elephant in the room, so I consulted Vanessa Machado de Olivera’s book, Hospicing Modernity, for some wisdom that might express my feelings and hopefully help us all to process the situation. I sent my proposed slides for the following week to my friend to check that they were appropriate.

My friend replied:

A word of caution against using any quoted abstraction about what ‘good’ or ‘better’ behaviour might be, regardless of how it seems a good direction to take [who would disagree with those ideas?], or even, whether an especially good female thinker has written it. Working from a ‘normative’ abstraction can be a [patriarchal] way of silencing/diminishing/categorising the lived experience of those on the inevitable other side when things don’t happen as they should. It can, also, close off the process for a difficult and necessary conversation if people feel they have to think it in abstract, normative terms. It depends on how it’s done.

There is I think, a lot of goodwill in the room, a lot of experience, and a lot of learning to do. And, it may have all blown over by Saturday.

WEEK 6. March 18. Nine people attended.

The final session arrived and although I had my slides in readiness, I did not project them but suggested that we talk openly about the issues that my friend had raised. It wasn’t easy and there were a few difficult moments. It will, of course, take a lot longer to truly resolve such contradictions, but we did open up ideas of ‘the male voice’ as the dominant conversation, and despite good intentions, how this links to social misogyny and by association racism and coloniality; subjects that I had tried to introduce earlier in the Talks, but that require much greater nuanced reflexivity. The key factor that the group, as a whole, focused on was education but were reluctant to let go of rationality as the pinnacle of human endeavor.

As the final session drew to a close, I reminded everyone that was, indeed, the last session in the series and thanked everyone for their contribution. I then asked if people wanted to continue in any way, they were perfectly at liberty to do so and that I no longer had any ownership of the idea nor further organisation. The group seemed a little sad that our talking adventure had come to an end, but they said they had enjoyed themselves. A Director of the venue said that he liked the title, ‘Talk in the Park’ and asked if he may use it for part of their Summer Programme. I was delighted to pass it on. A little time was spent thanking each other for all our input and I asked if anyone wanted to add anything or if they wanted to ask any questions. Two questions were asked:

- With the influx of people, migrants, and contract workers at BAE Systems, what will happen to Barrow’s culture; will it be overwhelmed?

- How can we retain Barrow’s culture and heritage?

History becoming futures

In 1840 Barrow was a tiny fishing village of about 150 people. By 1870 it had become a town of 19,000, with a railway, a port, docks, iron, and steelworks. The population was largely comprised of economic migrants from Cornwall, Ireland, and Scotland, including a sizable Indian community and some from China. In 1905 it was at the zenith of Britain’s Industrial Revolution and colonial Empire. From then until recently Barrow-in-Furness was largely regarded as a geographic and cultural backwater by the arts and media establishment. Indeed, the A590 road that ends in Barrow was referred to as the ‘longest cul-de-sac in Great Britain’. Each of these historic elements provides their own stories of what now weaves into a collective view of local heritage that has become the somewhat idealized myth of Barrow.

As I write this essay, the AUKUS alliance, with its $4.82bn contract for BAE Systems to build nuclear submarines, represents thirty-five years of assured future business. This means that the town is once again booming with a new BAE Systems training academy to occupy a redundant department store, new transport links, and an extra 5,000 jobs. Ancillary support services, construction, and manufacturing will increase that number greatly. Recent UK Government ‘Levelling-Up’ policies have included Arts Council England investment through its ‘Priority Places’ programme that has increased revenue support for existing and new arts organisations. But the question remains about local and wider perceptions of what constitutes culture in a town that, at the same time, has some of the highest deprivation, situated near some of the most beautiful UK coasts. As Welsh writer and commentator Raymond Williams noted: ‘Culture is one of the two or three most complicated words in the English language’[28] Perhaps that complicatedness also accounts for the paradoxical stories of Barrow-in-Furness and its particular culture.

David Haley

Walney Island

[1] Coleridge 1760

[2] Vanessa Andreotti (2015) Global citizenship education otherwise: pedagogical and theoretical insights”. In Ali Abdi, Lynette Shultz, and Tashika Pillay (Eds.) Decolonizing Global Citizenship Education. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

[3] Bryn Trescatheric (1998) The Last Place God Made: A History of Victorian Barrow

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_the_Tank_Engine

[5] https://www.royalnavy.mod.uk/news-and-latest-activity/operations/global/continuous-at-sea-deterrent#:~:text=For%2024%20hours%20a%20day,United%20Kingdom’s%20strategic%20nuclear%20deterrent.

[6] https://www.ons.gov.uk/visualisations/censusareachanges/E07000027

[7] https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/your-area/priority-places-and-levelling-culture-places

[8] https://bills.parliament.uk/bills/3155

[9] https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/03/13/joint-leaders-statement-on-aukus-2/

[10] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-cumbria-63227490

[11] https://www.welfare-state.org/

[12] https://thebarracudas.wordpress.com/about/

[13] http://www.furnessyouththeatre.com/

[14] https://www.art-gene.co.uk/

[15] https://signalfilmandmedia.com/

[17] https://ourladyoffurness.org.uk/

[18] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palace_of_Westminster

[19] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Centre_Pompidou

[20] https://rshp.com/projects/office/lloyds-of-london/

[21] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sydney_Opera_House

[22] https://www.visitlakedistrict.com/things-to-do/barrow-public-park-p1213731

[23] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ren%C3%A9_Descartes

[24] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imagine_%28John_Lennon_album%29

[25] Eduardo Paolozzi, (1985) “Lost Magic Kingdoms and Six Paper Moons from Nahuatl”. London: British Museum Publications.

[26] David Hockney (1998) dir. Phillip Haas. Day on the Grand Canal with the Emperor of China. Milestone Films https://milestonefilms.com/products/day-on-the-grand-canal-with-the-emperor-of-chinga

[27] Robert Maynard Pirsig.(1993) “Lila: An Inquiry Into Morals”. London: Black Swan.

[28] Williams, Raymond. (1988) “Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society”. London, Fontana Press, p 50 & 213

Add a Comment

Join our conversation