Introduction

New voices; imaginative approaches to engagement; integrated science, art, community, and education; joined artists and scientists and educators … sounds like I am talking about museums, botanical gardens, and other cultural institutions, no?

This roundtable explores the synergy between Nature-based Solutions (NbS) and sustainability professionals and a wide range of cultural institutions, including but not limited to ones normal focused on the environment in a traditional sense. Cultural institutions, within their particular but often broad focus (e.g., art, natural history, design, etc.) excel in engaging the public, something that NbS and sustainability discussions need to do better. By learning from their expertise in education, curation, and community outreach, sustainability professionals can amplify their impact—that is, better mainstream their ideas.

Here we use the term “cultural and educational institutions” in a broad sense, including both large to medium-scale science and art museums, small scale community arts centres and galleries, environmentally focused community education centres, and botanical gardens. What unites them is that they are all talented in connecting their topic areas to public audiences and are also deeply embedded in their communities and neighborhoods. They are trusted centers of community engagement and public informal education, and constitute important nodes in existing local cultural and civic networks.

Most such organizations are strong analogs to what we normally think of as the “entertainment industry” (concerts, movies, theatre, literature): they depend on delivering a product that the public finds valuable. That is, they sell tickets. When they don’t produce something the public finds useful, they will struggle to survive. For them, it cannot be only about the ideas. Connecting positively with the public isn’t a matter of good practice or items in grant agreements—it is how they survive.

Those of us to want to “sell” or otherwise spread ideas about sustainability, biodiversity loss, the climate crisis, NbS, and so on, could learn a lot from all that public engagement talent found in cultural institutions. If the state of the world is any indication, the folks trying to sell tickets about sustainability are not selling enough of them.

Sustainability and NbS practitioners and cultural and educational institutions have much to learn from each other for mutual benefit. Cultural and educational institutions of all sizes are natural partners for sustainability practitioners interested in broadening the reach and social acceptance of sustainability ideas. They can learn from cultural and educational institutions’ established culture and arts-based approaches to public awareness-raising and audience engagement how to deliver knowledge, spur interest, and connection with nature. Communication and messaging about sustainability, biodiversity, and NbS can be enhanced with these novel avenues, thereby creating a stronger base for developing deeper social connections with nature. This can translate into higher societal relevance and acceptance of nature as a source of social good and support mainstreaming “nature as culture” values. They can ignite the EU’s New European Bauhaus transition towards inclusive, sustainable, and beautiful places.

What’s in it for cultural and educational institutions? Well, in many ways, they are already doing it. But they too could benefit from collaborating with nature professionals as new sources of content/topics for hands-on exhibitions, educational tours, culture programming, and public engagement which can also help them broaden their visitor segments and audience. Further, they could learn from and benefit from established co-creation approaches in the NbS and sustainability community, which can support them in innovations for active ways to incorporate their ideas in the co-design and community-driven regeneration of nearby public spaces.

Such collaborations are emblematic of the kinds of rich transdiscipinary knowledge-building and community engagement many of us crave. Imagine an eminent art museum that conducts an annual festival on sustainability. Sure. The Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) is doing it already as the “Earth Rising” ecofestival. Imagine a natural history museum that has the audacious (and apparently rare) imagination to put actual living organisms in front of their building, instead of concrete statues. Yep. Someone is doing it. The Musuem für Naturkunde in Berlin installed a large native pollinator garden (“Pollinator Pathmaker: A living artwork for pollinators“) in front of their building, designed by an artist, no less. Both these organization are represented in this roundtable.

This roundtable includes a wide range of actors in these kinds of conversations. It includes educators, curators and scientists from cultural institutions, designers, NbS practitioners, artists, and policymakers to highlight how cultural institutions—and not just ones that are devoted to the environment—already serve as platforms for integrating scientific knowledge, cultural heritage, art, and local stewardship to support more sustainable and inclusive environmental practices.

Can the synergies of sustainability professionals and cultural institutions be mutually beneficial? Can we collaborate more? Can we blaze new trails? We certainly can.

about the writer

David Maddox

David loves urban spaces and nature. He loves creativity and collaboration. He loves theatre and music. In his life and work he has practiced in all of these as, in various moments, a scientist, a climate change researcher, a land steward, an ecological practitioner, composer, a playwright, a musician, an actor, and a theatre director. David's dad told him once that he needed a back up plan, something to "fall back on". So he bought a tuba.

Meriem Bouamrane and Thijs Biersteker

The science is clear. The policies are in place. But meaningful action remains elusive. To transform policy into reality, we need a societal shift—and societies shift rapidly when we can feel the facts. Scientists are sometimes hesitant, due to their training and field, to move beyond traditional presentation methods like posters. However, the urge for science to move at the speed of culture is pivotal at this moment in time. Even scientific research has demonstrated this need, as seen in the paper “Why Facts Don’t Change Minds: Insights from Cognitive Science for the Improved Communication of Conservation Research” by Anne H. Toomey, Department of Environmental Studies and Science, Pace University.

Scientists could get support to step away from the current culture of inward communication and empower a new generation of science communication. Cultural institutions are the tools to make people feel the facts, and to gain momentum and attention for issues that are normally confined to a paper or a fleeting headline.

UNESCO and renowned eco-artist Thijs Biersteker have explored this fruitful path for many years, proving at the highest levels that collaboration between biodiversity science and culture can communicate the world’s most urgent environmental issues. Their collaborative artworks focus on deforestation, restoration, and biodiversity indexing. They have been showcased at top conferences like the IUCN and COPs, but also at prestigious museums such as the Foundation Cartier in Paris and the Today Art Museum in Beijing. Their works have shown that the power of art, in all its forms, can extend research beyond experts, reaching heads of state and touching the hearts of the public.

Nature-based Solutions professionals can learn from cultural institutions the art of effective communication and engagement. Museums and botanical gardens have mastered translating complex scientific information into accessible, immersive experiences that resonate with a broad audience. By adopting these techniques, NbS professionals can present their research and solutions in ways that not only inform but also inspire action.

Cultural institutions excel at creating narratives that connect people emotionally to nature. They highlight the intrinsic value of biodiversity and the urgency of environmental issues through compelling visuals and interactive displays. NbS professionals can collaborate with these institutions to develop programs and exhibits that make nature-based solutions relatable to the public, helping to demystify scientific concepts and break down barriers between experts and non-experts.

The synergy between NbS initiatives and cultural institutions offers mutual benefits. For NbS professionals, collaborating with museums and botanical gardens amplifies their reach, allowing them to engage with a wider audience beyond the scientific community. It provides platforms designed for learning and reflection. For cultural institutions, integrating NbS themes enriches their educational offerings, aligning with their mission to foster understanding and appreciation of the natural world.

NbS professionals have much to learn from the strategies employed by cultural institutions. By leveraging storytelling, interactive engagement, and emotional resonance, they can enhance the impact of their work. Together, they can create experiences that inspire change, motivate action, and build a collective commitment to preserving our planet. This collaborative approach is essential for fostering the societal shift necessary to translate policy into meaningful action.

about the writer

Meriem Bouamrane

Meriem Bouamrane is an environmental economist and Senior Advisor for Nature-based Solutions Partnerships at UNESCO, where she focuses on developing cross-sectoral partnerships to advance climate action and biodiversity conservation. She served as Chief of Section for research and policy on biodiversity within UNESCO's Division of Ecological and Earth Sciences, as part of the MAB Programme, where she worked since 2001.

about the writer

Thijs Biersteker

Thijs Biersteker creates art installations that provoke insight into the ecological challenges ahead. In his practice, he collaborates with the world’s top scientists and institutions to turn their climate data into art installations that make the overwhelming challenges ahead accessible, understandable and relatable.

Carmen Bouyer

It is a pleasure to participate in this conversation, as my artistic practice has been evolving at the crossroads of environmental stewardship and art engagements for over a decade. I would like to contribute here by offering small examples of art projects I have facilitated that can show ways cultural institutions of various scales can collaborate with organizations implementing Nature-based Solutions (NbS). In all cases, some people act as bridges between the two fields of practice: artists and curators with an ecological awareness on one side and environmental stewards with an artistic sensitivity on the other. Here are three art projects that show the “ingredients” of those possible equations.

Art institution: Center for Arts and Innovation Pioneer Works, Brooklyn, NYC

+ Nature-based Solutions: Urban Agriculture Red Hook Farms (Brooklyn), Pioneer Works veggie garden (Brooklyn), Edgemere Farm (Queens)

+ Go-betweens: Urban farmers from each farm/garden, Corey Blant at Red Hook Farms, Marisa Prefer at Pioneer Works, Chef Anne-Apparu Hall, Environmental Activist Edward Hall, Artist Carmen Bouyer

= Hyper Local Community Meal hosted at Pioneer Works on a weekly basis, serving only New York City-grown fruits, veggies, and herbs, even wild edible plants picked in Central Park, highlighting urban agriculture potentials in an art context. An intimate way of connecting with the urban land by eating what it grows, while meeting your neighbors. This artistic experiment lasted six months in 2016 as part of an art residency. It initiated the community lunch program that lasted for seven years. The initial community meal program was coupled with a weekly CSA delivery, as well as street trees and shoreline ecosystems stewardship activities and art performances, supported by NYC Parks Super Steward program and the Greenbelt Native Plant Center.

Art institution: Art Festival Les Nuits des Forêts, happening yearly since 2020 in Fontainebleau Forest and various forests around France.

+Nature-based Solutions: Forestry Office National des Forêts (National Forest Agency)

+Go-betweens: Curators from COAL (Coalition for a Cultural Ecology), Sara Dufour, Lauranne Germond, Eco-psychologist Claire Tauty, Forester Alexandre Butin, Local inhabitants living by the Fontainebleau forest areas, Artist Carmen Bouyer.

= Forest Storytelling Art Installation presented in the Fontainebleau Forest, one hour away from Paris. Based on interviews from local residents and foresters, I have collected stories based on the prompt: If the forest could dream, what would it dream of? What are the dreams of the forest? Very site-specific and poetic stories were expressed, each highlighting very intimate relationships to this forested landscape. The stories were painted with ink on large rolls of paper suspended to trees and presented as an art installation “A quoi rêvent les forêts?” during the Festival Nuits des Forêts in 2022. Visitors could reflect on the Fontainebleau forest’s visions, hopes, and nightmares, strengthening a sense of empathy and wonder for the forest, highlighting the need for collective actions to protect it.

Art institution: Bookstore & Cultural Community Space S t o r m, Brooklyn, NYC

+Nature-based Solutions: Ecosystem regeneration with native plants

+Go-betweens: Curator Nour Sabbagh Chahal, Seed Program Administrator at Greenbelt Native Plant Center Seth August, Native Nursery Administrator at the Newtown Creek Alliance Brenda Suchilt, Artist Carmen Bouyer.

= Community Seed Collection Art Installation presented at Storm, composed of naturally dyed textile works representing native plants from the New York City area, the waters of the rivers and sea, and a large map adorned with necklaces filled with seeds. The installation “Adorning the Earth” was exhibited in the Fall of 2024, it is staying at the bookstore and serves as a community resource for future seed sawing in the neighborhood’s gardens and empty lots, especially the Newtown Creek and East River waterfronts, to support its local biodiversity.

These few examples connecting art with urban farming, forestry, or ecosystem regeneration all act at a very local scale, and in comparison, to big urban plans might seem tiny, but they are participating in the large web of small poetical encounters people are each crafting with land. Because these actions connecting environmental stewardship and art are highlighted by cultural institutions (in the context of exhibitions or events) their specific exposure and financial means can amplify hyper-local, often confidential, earth-based practices and in doing so slowly participate in institutionalizing a renewed culture of reciprocity with the land. A culture that takes shape in tangible ways through direct actions but also on an emotional level, as we softly expand our appreciation of the myriad of relationships we have with the more than human. In the invisible of our bodies, connections are rekindled, new paths open, older ones remembered and cherished.

about the writer

Carmen Bouyer

Carmen Bouyer is a French environmental artist and designer based in Paris.

Xavier Cortada

Empowering Change: How Art and Cultural Institutions Advance NbS Solutions

Throughout history, art has served as a universal language, handed down from our ancestors. It transcends time, culture, and geography, offering us the tools to connect, inspire, and communicate with one another in ways that words alone cannot. Today, as we face unprecedented environmental challenges, this ancient power of art can help us rediscover something deeply ingrained within us—our connection to nature. Nature-based solutions (NbS) are not foreign concepts to humanity. They are inherent within us because we are part of nature itself. Yet, over centuries, we have become increasingly disconnected from this understanding. Art can be the bridge that helps us reconnect with both each other and the natural world, fostering a deeper awareness of our shared humanity and the urgent need for change.

July 2024

In this moment of ecological crisis, it is clear that we cannot continue to engineer solutions that work in opposition to nature. As I wrote in “A 20-Foot Sea Wall is Not the Answer,1” the idea of building ever higher walls to protect against rising seas is emblematic of our misguided attempts to control and resist nature. Instead, we must move toward solutions that work in harmony with the natural world, and art can be instrumental in this shift. Art, as I have explored in “Reclaiming Art2” allows us to see the world differently, to question our assumptions, and to imagine new possibilities. It opens up creative ways of thinking and being, which are essential if humanity is to survive and thrive in the face of climate catastrophe. We need to press reset, to reconsider how we live, how we relate to the Earth, and how we can co-create a more sustainable future.

This is where cultural institutions such as museums and botanical gardens come into play. They serve as gathering places where art, science, and community intersect. By collaborating with Nature-based Solutions professionals, these institutions can help us collectively reimagine our relationship with the planet. In my Underwater Homeowners Association project3, I saw firsthand how the integration of art and environmental science can mobilize communities. The project used elevation data and art installations to engage Miami residents in discussions about sea level rise and climate adaptation. The act of creating something visual and participatory sparked not just awareness, but action—neighbors came together to problem-solve and advocate for change. It demonstrated the power of art to turn abstract concepts into tangible realities that people can engage with on a personal level.

Cultural institutions, with their established roles in education and outreach, are uniquely positioned to amplify the impact of NbS by bringing these kinds of interdisciplinary approaches to the forefront. As I argued in “The Underwater: Using Art to Engage Communities Around Climate Action4” art’s ability to engage diverse audiences is crucial for addressing complex environmental issues. By weaving together scientific knowledge and cultural heritage, museums and botanical gardens can help NbS professionals create spaces where communities not only learn about climate change but also feel empowered to act. This collaboration has the potential to shift the public’s perception of environmental challenges from distant threats to immediate, actionable concerns.

Underwater Bus Ft. Lauderdale, FL. March 2024

At the same time, these institutions stand to benefit from such partnerships. By incorporating NbS into their programming, museums and gardens can make themselves more relevant to contemporary issues, expanding their reach and deepening their impact. As I noted in “When it comes to climate, are cultural organizations breaking or losing ground?,5” art institutions are not just about preserving the past—they are vital platforms for dialogue, creativity, and innovation. The integration of NbS offers them fresh content and opportunities to engage with new, diverse audiences, particularly those who may not traditionally see themselves as part of the environmental movement.

In essence, the partnership between cultural institutions and Nature-based Solutions professionals represents a powerful synergy—one that not only helps us reconnect with the natural world but also challenges us to rethink how we engage with one another. Through this collaboration, we can build a more sustainable and inclusive future, rooted in creativity, connection, and a deep respect for the Earth.

1 “A 20-Foot Sea Wall is Not the Answer,” by Xavier Cortada, Biscayne Times, July 2021. See https://cortada.com/press/2021-press/a-20-foot-sea-wall-is-not-the-answer/

2 “Reclaiming Art.” By Xavier Cortada Posted in ARTSblog on November 9, 2011. See https://cortada.com/artist/writings/reclaiming-art/

3 See www.cortadafoundation.org/underwater

4 “The Underwater: Using Art to Engage Communities Around Climate Action,” 78 U. Mia, Rev. 519. Xavier Cortada (2024)

See https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr/vol78/iss2/8

5 “When it comes to climate, are cultural organizations breaking or losing ground?,” by Xavier Cortada, American for the Arts / ArtsLink, Fall/Winter 2022.

See https://cortada.com/wp-content/uploads/ 2022/12ArtsLink_Fall_Winter_2022_XavierCortada.pdf

about the writer

Xavier Cortada

Xavier Cortada, Miami’s pioneer eco-artist, uses art’s elasticity to work across disciplines to engage communities in problem-solving. Particularly environmentally focused, his work aims to generate awareness and action around climate change, sea level rise, and biodiversity loss. Over the past three decades, the Cuban-American artist has created more than 150 public artworks, installations, collaborative murals, and socially engaged projects.

Anna Cudny, Jan Chwedczuk, Artur Jerzy Filip, and Magda Maciąg

Blue-Green-Pink: NbS got under everyone’s skin already

Three years in a row, architecture students from Warsaw University of Technology, Faculty of Architecture, had the opportunity to design and build whatever they craved for, right in the middle of Warsaw. We—as the “:W CENTRUM” project curators—provided them with organizational and technical support, financial resources, necessary partners, intense mentoring, and each-year-different subject, such as water in 2022, urban noise in 2023, and costs of urbanization in 2024. Each year, the students’ work was supposed to be frosting on a cake of our broad, public, educational program.

With not even a slight push from our side, two in three editions we ended up with the NbS. It is in the air, no matter if we mention it or not. Consciously or subconsciously, it is already nested in students’ heads, in cultural institutions’ missions, in city authorities’ ambitions, in our business partners’ policies, in public opinion and media stories which we all are immersed in. As long as what we do looks like NbS, it gains broad acceptance easily.

On the first edition, which was devoted to water, NbS was almost too obvious. All our consultants and partners advocated for the NbS and provided the students with a bunch of inspiration and ready-to-take proposals. Not surprisingly, the students wanted to reach beyond what was obvious. They decided to go for a gallery-style work, presented as a piece of art together with a performative manifesto against excessive water consumption by the construction industry. “Wodny Azyl” (Water Refuge) was aesthetically produced and was absolutely right in its message, yet it was not a NbS and did not win much applause.

On the second year it was the opposite. The problem of urban noise was seen by most of our institutional and business partners as a purely technocratic issue, thus the solutions suggested were mainly about using innovative materials of special acoustic characteristics. The students once again decided to go contrarywise and designed the “HA-LAS” (“hałas” means noise in Polish, while “las” stands for a forest)—inspired by Shinrin-yoku (forest bathing) practice—which was more NbS that anyone could expect. The students built their HA-LAS in front of the main building of the Warsaw University of Technology, on the public square that normally remains empty of both greenery and people. Their intervention was absolutely surprising and accepted with excitement by the university students and staff, who all wanted it to remain permanent. Who wouldn’t love trees, indeed.

On the third year the very subject was highly abstract―it referred to the costs of architecture and urbanism. But after months of research and highly creative teamwork, our students came up with a proposal to grow over 30 square meters of pink oyster mushrooms right in the middle of the Five Corners Square, the newly renovated public space of Warsaw. The mushrooms filtered the air (pollution is considered one of the costs of urbanization), provided cheap yet nutritious food (only mushrooms that were not grown in traffic!), promoted organic aesthetics in architecture design, and ended up as good quality compost after the whole thing was dismantled and reused. This NbS was like nothing else before―the installation was seen by hundreds of thousands of passersby who shared comments and pictures on social media.

Surprisingly, NbS has become the easy way!

Along the way, we’ve learned that it is no challenge to go with NbS approach anymore. All these NbS-es happened by themselves. Whatever looks “green and blue” (or pink, sic!) wins acceptance and facilitates cooperation. For sure, NbS has become a new common denominator for professionals of all sectors—an easy starting point to gain cross-sectoral synergy, as well as a vehicle to reach broader audience!

about the writer

Anna Cudny

Anna Cudny, PhD - an architect, urban researcher and educator. She serves as an Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Architecture, Warsaw University of Technology, where she has been conducting courses on urban design since 2009.

about the writer

Jan Chwedczuk

Jan Chwedczuk – an architect at APA Wojciechowski and a lecturer at the Faculty of Architecture at the Warsaw University of Technology, where he teaches residential design. Active member of the Warsaw Branch of the Association of Polish Architects, a former vice-president for education, and a competition juror.

about the writer

Artur Jerzy Filip

Architect, researcher, and practitioner in the field of urban planning and design and author of the book “Big Plans in the Hands of Citizens”. He is the curator of the educational :WCENTRUM project. Assistant Professor at the Warsaw University of Technology, Faculty of Architecture.

about the writer

Magda Maciąg

Magda Maciąg - MSc Eng Arch, Graduate of the Faculty of Architecture of the Warsaw University of Technology, founder of the MUT architectural studio. Curator of the educational :WCENTRUM project, designer, curator and exhibition organizer, lecturer at the Vistula Academy of Finance and Business.

Edith and Jolly de Guzman

The Heart First, Then the Mind

In a previous roundtable essay for The Nature of Cities on co-creation of solutions by artists and scientists, we wrote about how connecting art and science can be an antidote to the predicament of content overload in a post-truth era. How do we break through the noise and cynicism to overcome complacency, overwhelm, and confusion?

Cultural institutions are positioned to do just that; they know how to connect through the heart first, and then the mind. Heart-first interactions enable us to experience both the familiar and the new, as well as the comfortable and uncomfortable with our guards down. Not so when we engage primarily analytically.

In his so-called “artistic proofs” Aristotle posited that in order to be truly persuasive, an argument must stand on three pillars: ethos (the ethical perspective), pathos (the emotional), and logos (the logical). As scientists and practitioners, many of us spend our time building a case for our work upon the pillars of the logical and the ethical. The currency of engagement that cultural institutions use gives equal (or greater) weight to the emotional perspective, trusting that tugging at the heart strings is a way to soon open up the logos of the mind and perhaps inspire us to change our ethos through action.

So how do cultural institutions lead with pathos, and what can we learn from them? Two ingredients that such institutions use regularly—which we could all benefit from more intentionally integrating into our work—are curiosity and wonderment. We can achieve this by incorporating dimensions we don’t typically associate with science (and only sometimes associate with practice). This can include weaving in beauty and elegance, as well as using familiar portals to introduce us to the peculiar and unconventional. It can manifest in the form of making connections with the historic and the nostalgic, linking us to the rich tapestry of human and ecological heritage. Or perhaps it can mean introducing us to connections to others in new ways. These and other pathways allow us to see ourselves in content that can still be deeply rooted in science and practice.

The two of us have been curating environmentally-themed art exhibitions for the past few years, which has been a transition for us. Edith previously engaged audiences only through research, demonstration projects, public policy, and planning, while Jolly engaged them through art and design. We’ve now integrated science-inspired art into our suite of engagement tools and it’s been an absolute delight to discover the breadth and depth of experiences that audiences reflect back to us.

One example was an outdoor public art installation we curated to raise awareness of shade as an equity issue in Los Angeles, which The Nature of Cities later transformed into a digital experience. Audience reactions revealed that many had never considered this topic before. This opened our eyes up to the reality that experiencing a topic is a much more inclusive and profound way to engage than simply seeing, hearing, or reading about it. We are excited to build off of this project with programming for Los Angeles County’s Descanso Gardens in the summer of 2025 with a series of garden installations, art exhibitions, and educational engagement events inviting visitors to connect to and cultivate an appreciation for the life-giving role trees play in making urban neighborhoods livable. Stay tuned for that, especially if you are in the Los Angeles area.

Another example was an interactive exhibit and accompanying event series to spread awareness about LA’s complicated relationship to water. One of the goals of that exhibit was for people to come away with greater trust in tap water when it comes from large, reputable water systems. Toward that end, we set up a blind water tasting station where participants sampled three brands of bottled water alongside tap water, recording their guesses about each. Many visitors expressed strong preferences about which brands they liked or didn’t like—even before the tasting began—but the blind tasting revealed those preferences were not really aligned with their taste buds. Most people guessed the wrong brands. In the end, tap water won out among many visitors, even those who pledged brand loyalty to bottled brands. This simply would not have happened if we led through analytical engagement rather than through experiences that disarm our rational defenses.

When we weave science and practice into programming offered by cultural institutions, we stand to make great gains in both directions. Not only do we advance engagement in the scientific and the practical, but we also deepen the impact of offerings that museums, galleries, botanic gardens, and other institutions give to the world.

about the writer

Edith de Guzman

Edith is a researcher-practitioner, educator & curator working with diverse audiences on climate change solutions. A cooperative extension specialist with UCLA, she investigates best practices for the sustainable transformation of cities. She has a PhD in environment & sustainability, a master’s in urban planning & a BA in history & art history. She can also be found hiking, playing guitar, or creating art exhibitions that explore the human-environment connection.

about the writer

Jolly de Guzman

Jolly de Guzman is an artist, graphic designer, and curator working in printmaking, photography, collage, drawing, sculpture, and giving new life to found objects. He is co-founder of the online art gallery and art+travel blog dearantler.com with his wife Edith (alongside a swanky eight-point buck named Jed Antler), where they exhibit artwork inspired by the human relationship to the environment, and their wilderness adventures to places near and far. He lives and works in Los Angeles

Susannah Drake

The 2010 Museum of Modern Art Rising Currents exhibition called attention to Manhattan’s oppositional relationship between the built city and water. My work with ARO on Rising Currents proposed an integrated and reciprocal organization of natural and engineered infrastructure systems. A combination of strategies, including perimeter wetlands, a raised edge and sponge slips combined with new upland street infrastructure systems, protects the island from flooding in response to climate change and related storm surge impacts.

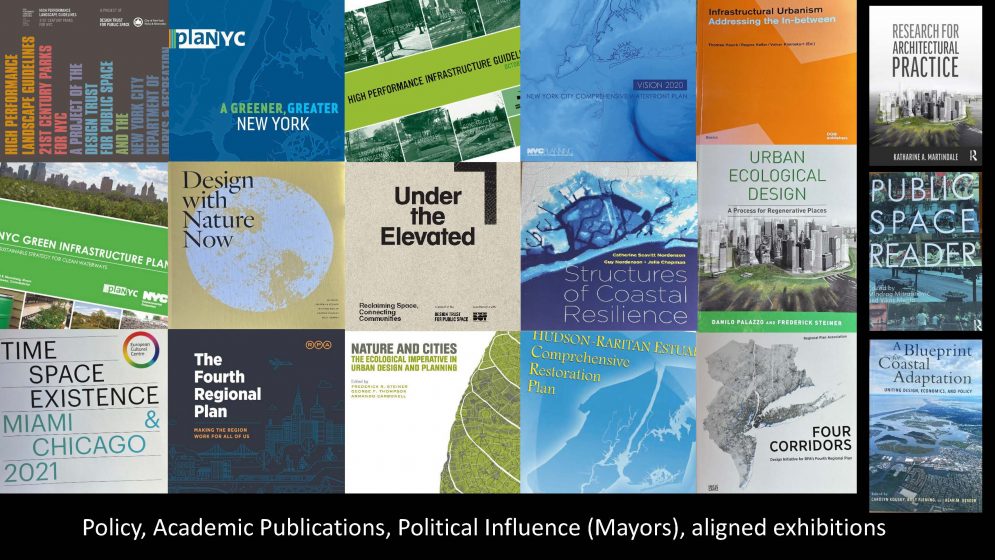

The proposal consisted of two components that form an interconnected system: porous green streets and a graduated edge. Rain events irrigate porous streets to maintain the health of upland and coastal ecologies. Three interrelated high-performance systems are constructed on the coast to mitigate sea level rise and storm surge force: a park network, freshwater wetlands, and brackish marshes. By aligning the advantages of naturally occurring and engineered systems, this new urban model proposed transforming the city in both performance and experience. A New Urban Ground is part of the permanent collections of the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum and The Museum of Modern Art.The work of Rising Currents had a tremendous impact on public policy, academic publication, political influence, and aligned work and exhibitions and work. PlaNYC, High Performance Infrastructure Guidelines, NYC Comprehensive Waterfront Vision, RPA Four Corridors Plan, RPA 4th Regional Plan, Design with Nature Now, and a Blueprint for Coastal Adaptation among many other publications were influenced by the work. Presentations to public agency officials influenced policy. Design studios about Rising Currents at schools across the influenced the next generation of designers and thought leaders.

Our image of Lower Manhattan surrounded by living shorelines is widely published as the enduring image of how to protect coastal cities. Rebuild by Design and opportunistic designers picked up on the potential marketing power of the site. The BIG-U as imagined by the Danish architecture firm BIG is the clear stepchild of the original planning. The plan lacks the integrated upland flood management component of our original design. In the rush to build something shiny and new, the plan also missed a tremendous opportunity for additional development space (housing!) on new elevated fill in the shallows of the East River. The original design kept existing parkland online for a generation of New Yorkers and preserved hundreds of mature trees. Sarah Bojsen, student at Cooper Union developed a brilliant thesis about the shortcomings of the Lower East Side Resilience (LES) aka BIG-U. Her work proposes alternate planning and design scenarios that are more inclusive of diverse populations, and more sensitive to climate change impacts on the neighborhood in both the short and long term. She is now pursuing a master’s degree in landscape architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. Her work will carry the torch of Rising Currents forward to the next generation.

about the writer

Susannah Drake

Susannah C. Drake FAIA FASLA is a Principal at Sasaki and founder of DLANDstudio. Susannah lectures globally about resilient urban design and has taught at Harvard, IIT, and the Cooper Union among others. Her award-winning work is consistently at the forefront of urban climate adaptation innovation. Most recently “From Redlining to Blue Zoning: Equity and Environmental Risk, Liberty City, Miami 2100,” was included in the 2023 Venice Biennale. Her first book “Gowanus Sponge Park,” was published by Park Books in 2024. Her work is in the permanent collection of MoMA.

Lisa Fitzsimons

Mainstreaming Nature-Based Solutions: The Role of Cultural Institutions

What if the answers to our biggest environmental challenges weren’t hidden in advanced technologies or far-off innovations but right in front of us, in the natural systems we often take for granted? Mainstreaming nature-based solutions (NbS) isn’t just about new science—it’s about changing how we see ourselves and our relationship with the world around us. It’s about recognising that humans are part of nature, not separate from it and that our well-being is directly tied to the health of natural ecosystems.

This mindset opens up extraordinary possibilities. By combining nature’s time-tested wisdom with the ingenuity of science and technology, we can create solutions that do more than sustain—they regenerate. These solutions have the potential to heal what’s been damaged. But if we’re serious about embedding NbS into everyday life, it’ll take more than policies or technical fixes. It will take people—engaged, inspired, and connected.

Community involvement is crucial because it bridges the gap between experts, policymakers, and everyday citizens. It ensures that these solutions aren’t just innovative but inclusive, impactful, and scalable. The challenges we face—climate change, pollution, and biodiversity loss—are enormous, and they require responses that are as creative as they are comprehensive. This is where cultural institutions can lead, serving as trusted spaces where science, art, and community come together.

The Unique Power of Cultural Institutions

Cultural institutions hold a quiet yet significant influence over societal values. Take museums, for instance. They’re among the most trusted institutions, with museum curators ranking alongside nurses and teachers in public confidence, according to the 2022 UK IPSO Veracity Index. This credibility gives them a unique platform to champion nature-based solutions.

By collaborating with NbS professionals, museums and other cultural spaces can connect the logic of science with the emotional pull of art. Art, after all, has a way of cutting through noise and reaching people in ways traditional methods often can’t. As Andrew Simms wrote in The Guardian, “For some, art may be a hammer with which to shape reality. For others, it’s a window opening on a world seen in a compelling new way. But it can also be a feather that tickles you through a difficult idea to a new understanding and frame of mind”.

Through exhibitions, performances, and creative programming, cultural institutions can spark reflection on our connection to the natural world. Art’s power to visualise complex issues and evoke emotion helps audiences engage with the Earth crisis on a personal level—and that emotional connection is a catalyst for action.

Collaboration for Impact

Cultural spaces are natural facilitators of dialogue, and that strength can be used to tackle environmental challenges. By partnering with NbS professionals, museums can help make these solutions relatable, linking them to cultural histories and visions for the future. Artistic practices, in particular, can evoke the emotional resonance needed to make environmental issues feel urgent and relatable, while science-based frameworks like biomimicry can anchor creative ideas in real-world applications.

Transforming Public Spaces

Cultural institutions often manage public spaces, which gives them the chance to show NbS in action. These spaces can be transformed into living, regenerative environments that engage communities and demonstrate the power of NbS.

Imagine public art installations that restore biodiversity, exhibitions that double as urban cooling solutions, or workshops where citizens design their own green interventions. These spaces can shift from places of observation to hubs of participation, blending ecological design with cultural programming to tackle environmental challenges head-on.

A Call to Action

By weaving the wisdom of nature into the stories we tell and the spaces we create, we can do more than address the Earth crisis—we can redefine how we live alongside the natural world. Cultural institutions, working alongside science and communities, hold the potential to inspire and lead this transformation.

Museums and cultural spaces are uniquely placed to ignite change. They can foster understanding, spark action, and build a vision of the future that is not just sustainable, but regenerative. Together, we can create a world where humans and nature thrive side by side—a world that is as culturally rich as it is ecologically vibrant.

about the writer

Lisa Fitzsimons

Lisa holds a MSc in Climate Change: Policy Media and Society from Dublin City University (DCU) and serves as the Strategy and Sustainability lead at the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) in Dublin.

Isobel Fletcher

On sitting down to answer this question, my initial thoughts are where do I even start? There is so much we, as NbS professionals can learn from cultural institutions. What strikes me first and foremost is that these creative and cultural institutions are front runners when it comes to engaging and involving many different citizen groups and communities with their offerings. To reach audiences beyond the “traditional” culture junkies, they have had to adapt their offerings, and present art, culture, nature, etc. in different formats that make the subject matter more accessible to a multiplicity of stakeholders. In doing so they continue to grow their reach and tap into new audiences.

How do they do this? Customer engagement and feedback I think has formed a large part―listening to what audiences like and dislike, what formats they engage with. Taking things like education and mental health seriously―crafting and creating programmes for people with Alzheimer’s, programmes for school children, even parent and child events. Being embedded in the local community, meeting local needs as well as catering to the tourist population who come to see national treasures. Listening and prioritising resources to engage with and learn from audiences, from the local community, and from stakeholders and then crafting exhibits, workshops and programmes for those diverse audiences that connect and resonate.

What we do know is that building relationships takes time and resources―and these both time and resources are often things that are not so readily available to nature-based solutions initiatives or the organisations that are driving them.

Certainly, since I started working in the world of nature-based solutions almost a decade ago, nature-based solutions have progressed from niche towards mainstream. There is a lot more knowledge around NbS but it still feels as though sometimes we are preaching to ourselves and that there are a lot of stakeholders that don’t really understand all that nature-based solutions offer. That combined with a sometimes validly held mistrust of authority where local planning decisions, building or demolition of community infrastructure has taken place with no community consultation or perhaps a menial community consultation only served to heighten tensions in the past between stakeholders and programme managers.

Consultation and engagement are different things and stakeholder engagement for me means building a connection, fostering a relationship and bringing your audience or stakeholders on a journey with you. It’s about building trust and a loyalty that goes both ways. In NbS, we need to build relationships with lots of different stakeholders over long periods of time. It’s not just about getting a project off the ground, NbS provide valuable services in so many ways from active climate prevention measures to providing social cohesion and economic opportunities―how we convey this messaging to stakeholders in a way that they can identify with and come on that NbS journey as active participants or sometime users. I think we could learn a lot from our partners and collaborators in cultural institutions on how to position NbS as centres of community with many different offerings for many different audiences by tapping onto their expertise on stakeholder engagement―learning how to draw out audiences and building trust and community.

about the writer

Isobel Fletcher

Isobel Fletcher is CEO Horizon Nua. Experienced project management professional with 25+ years’ working across Horizon Europe, Horizon 2020, FP7, LEADER and Lifelong learning programmes.

Todd Forrest

If botanical gardens didn’t exist, we would have to invent them so we could have the perfect vehicle for engaging people in Nature-based Solutions. Where else can one find the ready-made and eminently accessible combination of well-documented collections, educational and research facilities, biodiversity expertise, and diverse audiences who trust that expertise?

I imagine that many NbS practitioners and researchers already take advantage of botanical gardens’ unique scientific strengths through herbarium and library collections, plant biodiversity data, and research partnerships. I am certain many also participate in botanical gardens’ educational programs as instructors or students or both. But I wonder how many in the growing field of NbS look to living collections horticulture—the third leg of the botanical garden programmatic triangle—for inspiration or information?

Botanical garden horticulturists coax dense life out of disturbed ground—often in urban or peri-urban areas that have been altered physically, chemically, and biologically from their natural state. The horticultural problem-solving skills developed through efforts to assemble and cultivate rare and exotic plants in the most unlikely of settings will be essential in our efforts to successfully reestablish and enhance native plant biodiversity, particularly in the altered environments of cities, where native plants are increasingly becoming the rarest and most exotic of all.

As any gardener will tell you, it is never sufficient to just plant something and walk away. Yes, something will probably grow, but without thoughtful tending, it is unlikely to end up being the right plant in the right place. A garden without a gardener is fertile ground for failure. This may be the most important lesson that botanical garden horticulturists can share with NbS practitioners and researchers. To be successful over the long term, NbS, no matter where they are created, will need to be conceived with management in mind.

A genuine exchange of ideas between botanical garden horticulturists and NbS practitioners and researchers would be a boon to all. Botanical garden horticulturists care deeply about native plants and thriving ecosystems. They would love to see their callused hands, discerning eyes, and inquisitive minds put to use in the development and implementation of solutions to the growing climate and biodiversity crises. By seeking the counsel of skilled botanical garden gardeners, NbS practitioners and researchers would gain insights that would inform the design of effective NbS and plan and advocate for the resources required for their long-term stewardship.

Eventually, we are all going to realize that we are going to have to garden our way out of the climate and biodiversity crises. Botanical gardens are where that work should begin.

about the writer

Todd Forest

Todd Forrest is Arthur Ross Vice President for Horticulture and Living Collections at The New York Botanical Garden. He oversees the team of managers, horticulturists, and curators who steward the Garden’s plant collections, natural areas, gardens, and glasshouses and has been a leader in the development of the Garden’s celebrated program of interdisciplinary exhibitions.

Ewa Iwaszuk

As someone passionate about nature-based solutions (NbS), I’ve come to realize that working in this field isn’t only about proposing ecological interventions. It’s also about the art of communication, of convincing others that these solutions matter. Compared to many other fields of environmental policy—often framed around restrictions, bans, or phasing-out harmful practices—nature-based solutions offer a positive, often restorative path forward. Yet, the task of getting people on board remains a significant challenge.

Cultural institutions naturally cultivate an open mindset: they invite people to explore, reflect, and engage on a deeper, emotional level. Visitors are taken on a journey through time, across ideas, and into immersive worlds that make them feel part of something larger. So, I ask: how can we create a space for nature-based solutions where people come with the same curiosity, openness, and readiness to engage that they bring to museums or botanical gardens?

In museums, the artifacts, explanations, and interpretations are curated in ways that encourage exploration and interaction. This spatial and sensory immersion allows visitors to journey through knowledge and beauty, often connecting with them at multiple levels. Imagine, then, creating NbS projects that also serve as exhibits: rather than only focusing on the practical, we can design these spaces as immersive experiences, blending science and art to create installations that are as much exhibits as they are environmental interventions.

Such inspiring examples exist already: for instance, the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin, in collaboration with the Pollinator Pathmaker project, has created an outdoor space that invites visitors to see the world through the eyes of pollinators. Using an algorithm-based planting program, the garden brings in local species to attract pollinators, creating a beautiful living artwork that also educates and raises awareness about insect conservation. Visitors are exposed to science in a tangible, visually engaging way, where the garden itself becomes a story of biodiversity, art, and local ecology. Another model that blends the exhibit experience with nature-based solutions is the concept of “Edible Bus Stops” implemented in early 2010s in London, where community gardens were embedded in previously neglected urban transit spaces. Created to be both functional and beautiful, these gardens turned neglected patches of land into spaces that build community and promoted sustainable urban living.

Similarly, we could reimagine NbS projects as interactive installations in urban spaces, inviting communities to engage directly with rain gardens, pollinator-friendly landscapes, or even experimental urban wetlands. Just as a well-curated exhibit uses aesthetic appeal and narrative flow to captivate its audience, these NbS projects could use artistic elements, participatory design, and community-focused storytelling to turn everyday spaces into educational, ecological experiences. Imagine visiting a rain garden, where informational panels share insights on water management alongside beautiful native plants that you can touch, smell, and explore.

Engaging the public in environmental projects, however, goes beyond building something beautiful—it’s about creating a sense of involvement and personal connection. Here, too, NbS can take cues from cultural institutions. A London-based artist and engineer, Liliana Ortega Garza, developed a participatory labyrinth where people made decisions by choosing paths through a maze, illustrating the complexity of urban planning and stakeholder engagement in an accessible, playful way. Such immersive experiences demonstrate that participation can be more than a one-time event; it can be an ongoing journey that’s as playful as it is educational.

Imagine NbS community and cultural institutions coming together to design participatory experiences that engage the public through emotions, aesthetics, and learning. As we’ve seen in Berlin and London, the combination of art, science, and community can transform how we experience and value nature in urban spaces. By creating immersive exhibits around nature-based solutions, we’re not just adding greenery to our cities; we’re cultivating a public that feels genuinely connected to the solutions that sustain their environment. The journey towards a nature-positive future might just start with a simple visit to a garden, a bus stop, or a museum—a place where science meets art, and community meets nature―and land.

about the writer

Ewa Iwaszuk

Ewa Iwaszuk is a research fellow at Ecologic Institute. She focuses on climate and sustainability, with a particular interest in urban climate policy and nature-based solutions. She explores how cities can use natural systems to build resilience, address climate impacts, and support biodiversity. Ewa collaborates with various organizations to help develop practical strategies that make cities more sustainable and climate-friendly. Her work highlights the role of local governments in integrating nature into urban planning to create healthier, more resilient urban spaces.

Paola Lepori

I’m a museumgoer. I love museums. I love the most history, ethnographic and natural sciences museums. When I visit a new country, I do two things: I check out their national history museum and see if they have a natural history museum. Here in Belgium, my favourite museum is the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, which I visit at least a couple of times a year. I even have a museum pass that, for an annual fee, grants me unlimited access to hundreds of museums across the country. Did I mentioned I love museums?

Museums and other cultural institutions hold incredible power as places of culture, education, aggregation, and democracy. Could they be natural allies to help popularise nature-based solutions? The short answer is yes.

While museums didn’t start as places of education (early museums being mostly private collections and later becoming exhibitions of wonders and curiosities with little to be said about scientific rigour), they are today that amazing place where people of all ages can learn without the need of a book in hand, almost by osmosis, absorbing knowledge through their eyes and other senses. And that applies to other cultural institutions as well.

And the power of their reach is not lost to communication professionals either. A few years ago, I was working on the Our Ocean Conference. It was 2017. One of the themes of this high-level event was marine pollution. What better ally to campaign against marine pollution than an aquarium? And that’s how the awareness raising campaign World Aquariums Against Marine Litter came to be, involving dozens of aquariums across over thirty different countries. Participating institutions, real pros in scientific dissemination, showed tanks filled with plastic litter to explain visitors that, if nothing changes, by 2050 our ocean and seas will contain more plastic than fish. It’s almost redundant to point out that the impact of such a campaign, with the millions of visitors going through world aquariums each year, was bigger than any paid advertisement on commercials and billboards could have ever achieved.

There is more. Museums and other cultural institutions have evolved quite a bit, thanks to technological advancements and developments in the field of education and scientific dissemination. No longer are they just row upon row of display cases and dry labels. They purposefully make use of a variety of tools from audio guides to virtual reality to create immersive, interactive experiences. Is it time to forge a new alliance with these science communication powerhouses? Once again, the short answer is yes.

And the amazing thing is that, for us—nature-based solutions professional from policy makers to researchers and practitioners—there is plenty of choice. While natural sciences museums and botanical gardens might seem obvious partners, I like to imagine how cultural institutions dedicated to art and design would bring to life nature-based solutions, perhaps through virtual reality or experiential exhibitions.

Art is already a powerful tool in conservation education. According to Jacobson et al., “Using the arts for conservation can help attract new audiences, increase understanding, introduce new perspectives, and create a dialogue among diverse people. The arts–painting, photography, literature, theatre, and music―offer an emotional connection to nature”.[1]

That rings immediately true as I think of my own experience of reading the NBS Comics.

So yes, I can imagine a design museum where visitors are invited to imagine and co-create urban landscapes with nature-based solutions—green, lush, and beautiful. This would serve multiple purposes at the same time: it would rekindle the visitor’s connection with nature, it would empower the visitor to participate in the design of their urban living space, it would popularise nature-based solutions and raise awareness about their functions.

Ultimately, making space for nature-based solutions in museums and other cultural institutions, leveraging the enormous educational and congregating power of those institutions, could help make sure that, in the future, nature won’t be relegated to museums as a thing of the past we can no longer experience, but rather remains a living part of our world.

[1] https://academic.oup.com/book/26975/chapter-abstract/196171060?redirectedFrom=fulltext

about the writer

Paola Lepori

Paola Lepori is a Policy Officer for Nature-based Solutions at the European Commission, DG Research & Innovation. Her core professional objective is building alliances to trigger transformative change towards an inclusive nature-positive future.

Eleanor Ratcliffe, Terry Hartig, Alistair Griffiths, and Birgitta Gatersleben

In response to this question we offer perspectives from environmental psychology and horticultural science. We focus specifically on the intersection between botanical gardens as cultural institutions and as nature-based solutions (NbS) that support human wellbeing.

Terry Hartig, Uppsala University

Botanical gardens are often located within or near urban centres. Those that are thus become part of an urban green space structure, primarily valued by many residents and other visitors not because they offer possibilities to learn about particular plant species and biodiversity more generally, but rather because they are relatively quiet, sheltered places where those people can enjoy a calming respite surrounded by natural beauty. This is not to say the magnificence of the collections is unimportant, and once visitors to botanical gardens have come into a pleasant experience there they may be more open to some of the scientific information put before them as they move around. This kind of relationship between the experience of the garden, the acquisition of new knowledge, and the subsequent willingness to support conservation efforts in various ways is one of the concerns of the research we do at the Linnaean Gardens of Uppsala.

In brief, through the experiences they afford, botanical gardens can of themselves stand as an NbS for a different kind of pressing problem facing urbanized societies, a problem that apparently has contributed to the flooding, excessive heat, and other problems ordinarily addressed by NbS, namely, an all-too-persistent and all-too-widespread lack of appreciation for and understanding of the natural world and natural processes.

Alistair Griffiths, Royal Horticultural Society

NbS professionals can gain valuable insights and practical benefits from collaborations with botanical gardens. These cultural institutions have developed engaging ways of conveying scientific information and building public interest in environmental issues (see, e.g., RHS Hilltop, the UK’s first dedicated horticultural scientific centre of excellence, situated within RHS Garden Wisley). Botanical gardens’ participation in cross-disciplinary and cross-sector collaborations can enhance the design and implementation of wellbeing-focused NbS. For example, research at the University of Surrey and RHS Garden Wisley has shown that water, seating, views, and planting choices shape emotional experiences in a Wellbeing Garden. Interactive exhibits in botanical gardens can also help people to visualise the benefits of NbS, which RHS is using to research emotional preferences for plant colours, scents, and flower shapes. These insights are valuable for both NbS practitioners and botanical gardens in enhancing visitor experiences. RHS has also partnered with the National Health Service to create health-centred wellbeing spaces around England.

Further, botanical gardens play a crucial role in delivering benefits for people and nature via outreach programs (e.g., RHS It’s Your Neighbourhood; RHS Britain in Bloom) which make positive differences nationwide. As a charity, RHS freely shares knowledge online, reaching nearly 30 million people across the UK—a powerful force for societal influence on nature-based solutions.

Eleanor Ratcliffe and Birgitta Gatersleben, University of Surrey

Botanical gardens tend to be high-profile tourist attractions. NbS practitioners can benefit from this footfall by developing, e.g., nature for wellbeing solutions within or close to the gardens, and by learning from the engagement strategies used by botanical gardens to increase awareness of NbS. However, equality/equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) should be key points for consideration by both NbS practitioners and cultural organisations. Botanical gardens tend to attract visitors who are mainly white, middle-class, and of older age (BCGI, 2011). Cultural stereotypes about ‘who botanical gardens are for’ means that certain demographic sectors of society may be less inclined, or less able, to visit and derive benefits from these spaces. Organisational strategies (e.g., EDI Charter for Horticulture, Arboriculture, Landscaping, and Garden Media Sector) and programming decisions can highlight EDI topics and emphasise that botanical gardens are for everyone (e.g., Kew Gardens’ 2023 festival Queer Nature and their dementia-friendly health walks, and RHS Bridgewater Garden’s celebration of Pride in Nature).

Further, given the connections between many botanical gardens and colonialism, some institutions are taking steps to decolonise their collections (e.g., Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh)―an important part of challenging deeply-rooted power relations. NbS practitioners can learn from and build on these actions, to ensure that wellbeing-focused NbS are context-sensitive and welcoming to all.

about the writer

Eleanor Ratcliffe

Eleanor Ratcliffe is a Senior Lecturer in Environmental Psychology and a Fellow of the Institute for Sustainability at University of Surrey, UK. She is a Board member of the International Association of People-Environment Studies and programme lead for Surrey’s MSc Environmental Psychology.

about the writer

Terry Hartig

Terry Hartig works as Professor of Environmental Psychology at Uppsala University in Sweden. He has extensive experience in research on the experience of nature and environmental supports for restorative processes.

about the writer

Alistair Griffiths

Alistair Griffiths is Director of Science and Collections at the Royal Horticultural Society, a member of the RHS Executive Leadership team, and a Visiting Professor at Royal Holloway, University of London.

about the writer

Birgitta Gatersleben

Birgitta Gatersleben is a Professor of Environmental Psychology at University of Surrey and leads its Environmental Psychology Research Group. Birgitta is co-director of the ESRC-funded ACCESS network which champions environmental social science to tackle environmental challenges.

Baixo Ribeiro

This year, I was invited to participate in a project where I would lead the efforts to direct a regional art collection―a wonderful compilation of paintings and sculptures from the 19th and 20th centuries―featuring artists from the state of Rio Grande do Sul (the southernmost part of Brazil). My contractor was a bank socialized in “student credit” for working-class families. After several meetings, we arrived at a draft strategy to promote the art collection to a broad audience, with the participation of the young people, who are the focus of student loans.

The central idea was to listen to students about the themes addressed in the works of the collection, that is, to connect art and audience through topics of common interest. We defined the field from which we would extract the themes: the climate future. This field was chosen due to the urgency of the issue and the necessity to consider climate change in all projects involving youth, and thus the future. Incorporating the climate issue into projects with a temporal reach ensures that participants are not caught off guard by serious climate changes during the course of the projects―situations we must always account for. We proceeded similarly regarding the future of the regional art collection we were dealing with. Everything seemed a bit theoretical, and the participants in this process were engaged, but there was not much conviction that we were focusing on the best area of interest. However, before the skeptics could outnumber the believers in the project’s guidelines, Rio Grande do Sul was struck by a terrible climate disaster, and the state was flooded by intense rains. All cities were affected, and many were completely submerged and isolated. It took several months for everything to “return to normal”. But nothing returned to normal, actually…

After reconstruction began, it became clear that all structures needed to be rethought to withstand new climate patterns―otherwise, suffering tends will multiply. This new situation certainly altered people’s perceptions regarding the art collection project. The climate issue was solidified as the very central theme of the project, meaning that climate became the main driver for engagement with the project. Finally, we decided to schedule a Youth Climate Forum in 2025, which will serve as a basis for listening to new generations about the climate future. The purpose of the Forum is to gather insights on the vulnerability of the population (especially the poorest) in cases of disasters and to raise ideas that can be taken to COP30, which will follow in the Amazon (in the northern part of the country).

What does climate have to do with the historic art collection that originated and is, after all, the central reason for the project? The academic works from the 19th century present in the collection showcase many local landscapes and also portraits of the people who lived there. These academic paintings contrast with many modern works, especially those that glorify industrial progress and consumer society. The idea is to encourage discussion about past customs that interfere with the present. Consequently, we aim to discuss how to influence the future through actions taken in the present.

about the writer

Baixo Ribeiro

Baixo is President of the Choque Cultural gallery in São Paulo.

Daniela Rizzi

Lessons from Museums for the Nature-Based Solutions Community and Vice-Versa

NbS professionals, including scientists and practitioners, play a pivotal role in addressing urgent global challenges such as biodiversity loss, climate change, and ecosystem degradation. Yet, effectively communicating the significance of NbS to a broader public often remains a challenge. Cultural institutions, particularly museums, have a long-standing tradition of transforming complex concepts into engaging and accessible experiences for diverse audiences. This expertise offers rich inspiration for NbS professionals seeking to enhance the impact of their research and practices. At the same time, NbS experts can inspire museums to bring biodiversity and environmental challenges closer to their visitors, creating a mutually enriching relationship.

Museums excel at storytelling, which allows them to connect with visitors on an emotional and intellectual level. They craft narratives that resonate, whether through historical artefacts, artistic interpretations, or thematic exhibits. NbS experts can learn from this by embedding their research findings into compelling stories that highlight the human and ecological dimensions of their work. For example, the story of a restored mangrove forest could illustrate how NbS not only protect coastlines from rising seas but also revitalise local livelihoods and biodiversity. These narratives can help make abstract scientific findings more tangible, relatable, and memorable for audiences.

Visual and interactive engagement is another area where museums thrive. From immersive installations to augmented reality displays, museums use creative formats to captivate their audiences and encourage exploration. Similarly, NbS professionals could use virtual reality to simulate the transformation of urban areas with green roofs or wetlands, allowing audiences to see the potential impacts of implementing NbS firsthand. Interactive models of sustainable landscapes or demonstrations of ecological processes could further spark curiosity and deepen understanding. By making NbS projects visually and experientially engaging, experts can bridge the gap between data and public awareness.

Inclusivity is a hallmark of museum design, as exhibits are crafted to appeal to a range of ages, educational levels, and cultural backgrounds. NbS professionals could emulate this approach by tailoring their communication strategies to specific audiences, such as children, policymakers, or business leaders. Educational kits, community workshops, or even artistic collaborations inspired by museum practices could help NbS professionals share their knowledge in formats that resonate with different groups. This inclusivity ensures that no audience is left behind in the drive to promote a nature-positive future.

While museums provide a wealth of communication tools for NbS professionals, the exchange of inspiration is far from one-sided. NbS experts can bring invaluable insights to museums, enabling these cultural institutions to engage more deeply with pressing environmental issues. By collaborating with museums, NbS professionals can help curate exhibitions that focus on the importance of biodiversity, ecosystem restoration, and climate resilience. These exhibitions could showcase real-world examples of NbS projects, highlighting their potential to create harmonious relationships between humans and nature.

Museums also have the potential to amplify the local-global connections inherent in NbS work. Many NbS initiatives are rooted in specific local contexts but contribute to broader global goals, such as those outlined in the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. Museums could use this knowledge to create exhibits that bridge local narratives with global environmental challenges, helping visitors understand how their actions and communities are linked to planetary health. This contextualisation empowers individuals to see themselves as active participants in global efforts to combat biodiversity loss and climate change.

Furthermore, collaboration between museums and NbS professionals could lead to dynamic educational programming. Workshops, public lectures, and interactive activities co-developed by both entities could provide hands-on experiences for visitors, such as planting pollinator gardens or designing urban green spaces. These initiatives not only educate but also inspire action, turning museum-goers into advocates for biodiversity and a nature-positive lifestyle.

The synergy between NbS professionals and museums represents a powerful opportunity to reframe how society engages with biodiversity and climate solutions. By adopting the creative communication strategies of museums, NbS experts can reach broader and more diverse audiences, making their work accessible, relatable, and impactful. Conversely, museums can draw on the expertise of NbS professionals to integrate contemporary environmental challenges into their cultural narratives, fostering greater public awareness and engagement.

In a time of ecological crisis, these partnerships have the potential to spark transformative change. Together, museums and NbS professionals can cultivate a deeper understanding of humanity’s interdependence with nature, inspiring collective action to protect and restore the ecosystems on which we all depend.

about the writer

Daniela Rizzi

Architect/urban planner (Faculty of Architecture & Urbanism of the University of Sao Paulo). Holds a doctoral degree in landscape architecture and planning (Technical University of Munich). Senior expert on Nature-based Solutions and Biodiversity at ICLEI Europe (ICLEI Europe).

David Skelley

Last week, I returned from an external review of the Natural History Museum of Utah. NHMU is one of the premier university-based natural history museums in the U.S. with an annual attendance of 350,000 visitors in Salt Lake City and school visits across the state that reach many more―as the state museum, NHMU has the mandate to reach each of the state’s 4th grade classrooms. The Museum building is at the edge of campus in the foothills of the Wasatch range on a site crossed by the Bonneville Shoreline Trail which follows the edge of prehistoric Lake Bonneville. The Trail is used by millions of hikers and bikers each year.

A centerpiece of the NHMU strategic plan is a goal of achieving zero carbon emissions. The Museum is seen by the Provost of the University of Utah, the Museum’s parent institution, as the leading edge of an effort that will eventually spread across the campus. The leadership of the Museum has a basic understanding of the range of technologies available to achieve this goal, but they would not consider themselves experts in this realm. Their expertise is in connecting their visitors with both the physical and natural world and with the ideas that help us understand its state and its future. And that is the opportunity for NbS practitioners.

On my own campus, the Peabody Museum will be holding a press preview tomorrow morning for a temporary exhibition on the brain entitled Mind/Matter: the Neuroscience of Attention, Memory, and Perception. Our curators and staff have very little understanding of neuroscience. But our colleagues across campus at the Wu Tsai Institute are among the best neuroscientists on the planet. We turned to neuroscientists from the WTI For their leadership in curating the exhibition―an experience that was entirely new to them. In turn, the Peabody has never hosted an exhibit on neuroscience. But this model of fusion―between those who know about the world and those who know how to share that knowledge―is what museums like NHMU and the Peabody do every day.

The zero carbon initiative at NHMU is at a much earlier stage but it can follow a similar path. Museum professionals will need to work with NbS experts to learn what is possible and to consider ways of making it legible and impactful to their visitors. The Museum opened an exhibit recently entitled Climate of Hope to introduce visitors, especially children, to the facts of climate change and the range of possibilities for the future. An exhibition highlighting the Museum’s own efforts to use NbS to achieve zero carbon emissions could be a powerful pairing with this exhibit which would help millions of people understand NbS.

This power comes from the standing of natural history museums. They are among the most trusted institutions in the United States, where trust in any institutions has been ebbing for the last decade. Part of that trust comes from the fundamental relationship between a museum and a visitor. Natural history museums were founded on their collections―the physical evidence. Museums still use evidence to reach conclusions and to invite visitors to consider that evidence for themselves. This is a form of trust that needs to be placed front and center in any effort to get the public on board with NbS. Collaborations with museums could be one of the most effective ways to show the public what NbS is in a setting where visitors are expecting to see scientific innovation and to be encouraged to understand what they could mean for our future.

about the writer

David Skelly

David Skelly, Ph.D., is the Frank R. Oastler Professor of Ecology at the Yale School of the Environment and the Director of the Yale Peabody Museum. His research focuses on rapid evolution and other means by which wildlife species are responding to human changes to landscapes and climate.

Ulrike Sturm and Marius Oesterheld

We believe the synergies between Nature-based Solutions (NbS) and cultural institutions can definitely be mutually beneficial. In our response we will focus on what NbS professionals can learn from cultural institutions, particularly in terms of how they engage the public, build partnerships, and foster a deeper understanding of ecological issues.

One key takeaway from cultural institutions is the art of effective public engagement and communication. For example, natural history museums engage visitors in accessible, interactive ways around complex topics like biodiversity and evolution. Their approach of blending scientific knowledge with creative storytelling and hands-on exhibits makes these topics relatable and meaningful to a wide audience. NbS projects could adopt similar strategies to make ecological concepts more understandable and engaging for diverse communities. By partnering with museums and botanical gardens, NbS professionals could leverage established networks and platforms to raise awareness and foster public understanding of the socio-ecological challenges we face.

Additionally, cultural institutions often bring valuable expertise in designing and implementing participatory formats, such as citizen science projects, living labs or co-design workshops, which invite public involvement in scientific research and innovation. Through such approaches, museums have empowered individuals to contribute to research on biodiversity, climate change, and other environmental challenges, fostering a sense of ownership and active participation in science. This approach is highly applicable to NbS initiatives, where local knowledge and community engagement are crucial for success. By drawing on the participatory expertise of museums, NbS initiatives can create more inclusive and responsive projects in conversation with the people they aim to benefit. In particular, NbS professionals could work with museums to document traditional ecological knowledge or develop participatory programs that blend scientific insights with indigenous and community-based knowledge, creating a more comprehensive approach to NbS.