Introduction

about the writer

Bettina Wilk

Bettina Wilk is a sustainable urban development practitioner with expertise in nature-based solutions, urban resilience, and environmental governance. Bettina has worked with local authorities on policy integration, nature-inclusive urban planning and governance (Urban Nature Plans, EU Nature Restoration Law) with ICLEI Europe. She now leads projects and services development on urban nature at The Nature of Cities Europe, fostering strategic partnerships to advance sustainable urban futures.

The first EU-wide legislation for large-scale ecosystem restoration was adopted in August last year, with legally binding, time-bound targets for all relevant ecosystems. The EU Nature Restoration Law was celebrated as a game changer in the fight against biodiversity loss and climate change impacts. However, its adoption was highly controversial, and proponents raised concerns about ecosystem targets being watered down for the law to pass.

Implementation will be a challenge―as we have learned from previous policies and commitments, such as the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2020, the EU Nature Directives, and the Aichi Targets.

The regulation’s success depends on its effective implementation by EU Member States. As the first important stepping stone, 2025 is the year for all the Member States to develop coherent, inclusive, and well-resourced National Restoration Plans (due Sept. 2026).

With important policy frameworks and regulations in place at the EU and international levels, what are the prospects for the implementation of the EU Nature Restoration Law? Will it be possible to set aside sectoral divides for joint, effective actions? Or does implementation―once more―run the danger of lagging behind its ambitious targets? How do we ensure scaled and timely actions in response to the urgency of the dual climate and biodiversity crises? And what are the alternatives?

This roundtable explores diverse perspectives on putting the EU Nature Restoration Law into action, considering global developments at CBD COP16 and the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF). It includes policymakers and policy think tanks, landscape architects, representatives of landowners, local and national authorities and city planners, ecosystem restoration practitioners and scientists, youth representatives, and business voices.

Humberto Delgado Rosa

about the writer

Humberto Delgado Rosa

Humberto Delgado Rosa is the Director for Biodiversity, DG Environment, European Commission. Previously he was Director for Mainstreaming Adaptation and Low Carbon Technology in DG Climate Action. He is experienced in European and international environmental policy, particularly in biodiversity and climate change issues.

With important policy frameworks and commitments in place at the EU and international level, what are the prospects for the implementation of the EU Nature Restoration Regulation?

It’s been a busy five years, and we have faced some real challenges to get the Nature Restoration Regulation in place, but this is the nature of the law-making process, and it serves a real purpose. It’s what the negotiations are for, and why we have a co-legislation process. It should not be seen as a negative process, but a collaborative one, that can improve the quality and acceptance of legislation. The process can actually improve the prospects for implementation. In some cases, the text was strengthened, for example in the case of the targets for pollinators, and in others, it was softened but, in the end, it may have become more realistically implementable, while remaining quite ambitious. Different stakeholders had different views, of course. The involvement of all actors in the process, national and local administrations, members of the European Parliament, NGOs, scientists, along with Commission officials, have produced a Regulation that is, in my view, well-balanced and genuinely implementable.

In the context of our EU and international commitments, it is an essential piece of the jigsaw. It cannot be understated how significant it is that we have the Nature Restoration Regulation in place, to give credibility to our position on the global stage. The Nature Restoration Regulation will help the EU and its Member States to meet their international commitments to restoration under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework adopted in December 2022. It is a ground-breaking piece of law, that shows how committed and serious we are, and that we are not just talking the talk, but also walking the walk. The Commission is now working intensely with the Member States towards implementation, starting with the development of the National Restoration Plans and the development of guidance material.

Will it be possible to set aside sectoral divides for joint, effective actions? Or does implementation―once more―run the danger of lagging behind its ambitious targets?

I am convinced that any differences of opinion that were seen during the negotiations will now be progressively set aside and that we can work together toward effective implementation. Indeed, implementation of the Regulation has already started well, with conversations underway in the EU Biodiversity Platform on how best to establish the National Restoration Plans.

The Nature Restoration Regulation builds on existing nature legislation, adding binding, quantitative, and time-bound targets. It is now in force and is binding to the Member States. Although we often hear stories about breaches of environmental laws, we should remember that a vast majority of our laws are implemented and complied with; and for those that are not, the Commission has the possibility to take action to make sure they are, which we often do. I feel confident about the implementation of the Nature Restoration Law. If you take the time to read it, not just the headlines in the press, you will see that it has a strong focus on building resilience, improving knowledge, on measuring and monitoring, and on setting targets in an open and transparent way so as to get back more of the ecosystem services that we need. Implementing the Regulation will involve cross-cutting cooperation, between different departments of national, regional, and local authorities as well as the involvement of stakeholders such as farmers, foresters, fishers and landowners. There is flexibility to allow for Member States to develop their national restoration plans according to their needs and circumstances and develop measures that are effective and meaningful for them. That is why I am confident that the overall targets of the Nature Restoration Regulation can and will be met.

How do we ensure scaled and timely actions in response to the urgency of the dual climate and biodiversity crises? And what are the alternatives?

For too long the climate and biodiversity crises have been seen as two separate challenges to tackle, and they are not. They are part and parcel of the same crisis, the crisis of degradation of the biosphere due to human activities. We need to tackle them together if we are to secure our own future. This fact has been well recognised in the Green Deal and in the 2030 Biodiversity Strategy, and it has been a fundamental part of the development of the Nature Restoration Regulation. From the impact assessment to the choice of ecosystems and their targets, the relationship between restoration and climate change has been key. The Nature Restoration Regulation can be seen as a climate-related policy. We have not only set out to restore ecosystems for the sake of nature (although this is a meaningful action in itself in my opinion) but also to make a major contribution to meeting our climate change mitigation and adaptation targets, and for the many other ecosystem services we depend on.

Using Nature-Based Solutions has been shown time and time again to be a cost-effective way to reduce impacts of climate change and extreme weather events while being cost-effective and having many additional benefits to society. Our green space and tree canopy cover targets are an excellent example of this: urban green space is not only fantastic for local biodiversity (including birds and pollinators), and not only can it improve the mental and physical well-being of citizens, but it also helps to filter pollution and regulate climate. Nature in cities acts as a ‘sponge’ for rainwater, helping to protect against flooding, and at the same time helps significantly cool cities, much more cost-effectively than using air conditioning.

We have to take action now and we have to use nature and work with nature to tackle the urgent challenges we face. There is no alternative.

Liviu Bailesteanu and Bogdan Micu

about the writer

Liviu Bailesteanu

Liviu Bailesteanu acts as co-coordinator of the Greening Cities Partnership, under the Urban Agenda for the EU. He has been working at the Romanian Ministry of Development, Public Works and Administration since 2008. In 2017 he became Director of the Policy and Strategy Directorate, being responsible for informal cooperation in the areas of territorial cohesion and urban development, as well as for ensuring the national strategic framework for these areas.

about the writer

Bogdan Micu

Bogdan Micu is a geographer based in Bucharest with over 7 years of experience in spatial policy and planning. He currently works for the Romanian Ministry of Development, Public Works and Administration, implementing, monitoring and evaluating national strategy and policy, performing GIS modelling and analysis, as well as liaising with EU institutions on urban matters, including the Urban Agenda for the EU.

Pragmatic Considerations on Implementing the Nature Restoration Regulation

While the Nature restoration regulation (Regulation (EU) 2024/1991) is seen as an important step toward the goals of climate mitigation and ecosystems health, we do recognise that its successful implementation will require overcoming certain challenges through effective policy design, adequate funding, collaboration among diverse stakeholders, and long-term planning. Most of these issues are well-known to policymakers and practitioners, so we will only echo the most obvious ones based on our experience with similar initiatives:

Public support

While nature restoration is broadly supported by the public in principle, the actual implementation may face resistance, particularly if local communities feel that it could negatively impact their livelihoods or quality of life. There may also be skepticism about the benefits of restoration or concerns about the costs involved.

Aligning private sector incentives with public policy goals can also be difficult, and the long-term nature of restoration efforts may not always match with short-term business interests. This usually spills over into the political arena, and political will to implement nature restoration plans may fluctuate, particularly in countries where there is resistance from industry groups or where economic pressures take priority over environmental concerns.

Social considerations

Successful restoration requires engaging local communities and ensuring that they benefit from the projects. If the communities do not see the value or if they are excluded from the planning process, the chances of success diminish. Restoration efforts need to balance ecological goals with the needs of local populations, ensuring that they are not unduly harmed.

Financial constraints

Large-scale restoration projects require substantial financial resources and the involvement of the private sector. Many member states, particularly those with less economic capacity, may struggle to allocate the necessary funding, both from public budgets and private investments. Furthermore, restoration efforts can be time-consuming, and measuring the long-term cost-effectiveness of restoration is difficult. As such, securing consistent funding for long-term projects will remain a challenge.

Legal barriers

Nature restoration involves multiple stakeholders at various levels (EU, national, regional, and local), and ensuring effective coordination and cooperation can be difficult. Different member states have varying legal frameworks and regulatory standards for land use, conservation, and environmental protection. Harmonising these approaches while adhering to EU guidelines is a complex task.

Land-use conflicts

Restoring land for nature may compete with agricultural and forestry activities, which are critical for the economy in many rural areas. Farmers and landowners may resist changes to land use, fearing that it will limit their ability to produce food or timber, or even reduce property value. Restoration efforts need to balance ecological goals with the needs of local populations, ensuring that they are not unduly harmed.

The need for restoration may also conflict with ongoing or planned infrastructure projects like roads, buildings, and energy facilities, especially in densely populated or industrialised areas.

Technical challenges

Effective restoration requires reliable baseline data and long-term monitoring to track progress. Many ecosystems have been so degraded that it’s difficult to assess their potential for restoration, and monitoring methods may not be sufficiently advanced or standardised across the EU.

Since there is no one-size-fits-all solution for ecosystem restoration, the effectiveness of restoration techniques can vary greatly depending on the type of habitat, species involved, and local conditions. Developing and scaling up effective restoration methods is a significant challenge.

It must also be said that ecological restoration outcomes can be slow, and benefits are often long-term and difficult to quantify. Accurate reporting and transparent monitoring mechanisms will be crucial for holding stakeholders accountable and ensuring that restoration goals are met.

Local contexts

The EU regulation aims to restore ecosystems across a wide range of landscapes, from forests to wetlands to agricultural areas. However, local contexts and specific ecosystem needs will require tailored approaches, which may complicate implementation. What works in one region or habitat type might not be applicable in another.

In some cases, the ecosystems being restored have experienced irreversible damage, and restoring them to their original state may be unrealistic. In such cases, creating resilient ecosystems that support biodiversity may be more practical than restoring a specific habitat.

Chiara Baldacchini and Carlo Calfapietra

about the writer

Chiara Baldacchini

Chiara Baldacchini is an Associate Professor in Applied Physics at University of Tuscia (Viterbo, Italy). She is an expert in Nature-based Solutions implementation and impact monitoring, involved in projects and taskforces at European level and in the NbS-related activities of the Italian National Biodiversity Future Centre. She is the Vice-Coordinator of the NbS Italy Hub and represents the Italian Ministry of University and Research within the Biodiversa+ partnership.

about the writer

Carlo Calfapietra

Carlo Calfapietra is the Director of the Institute of Research on Terrestrial Ecosystems (IRET) of the National Research Council of Italy (CNR). He is expert in Nature-based Solutions and particularly in the relationships between vegetation and the environment. He is responsible of CNR for the National Biodiversity Future Centre and Coordinator of the NbS Italy Hub.

The Nature Restoration Law (NRL) is the first comprehensive continental-level law of its kind, and its implementation will contribute not only to reducing biodiversity losses and to mitigate climate changes but also to the safeguard of human health and well-being.

The process for implementing the NRL at the level of EU Membre States has already started, and big efforts are now required at a national level to prepare the National Restoration Plans (NRP; due in 2026), which should include the restoration of at least 20% of the EU’s land and sea areas by 2030. This is an ambitious target, but the presence of a strict protocol would increase the probability of success.

To facilitate the process, it would be important to take advantage of the initiatives already put into action, such as the Natura 2000 network (in which priority actions by 2030 are already planned), the National Plans for Recovery and Resilience (NPRR; funded by the EU upon the pandemic), or the National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (which should drive the implementation at a national level of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework).

Also, setting aside sectoral divides would be mandatory to reach the NRL targets, and synergies should be put into action across all sectors of society, as ecosystem restoration must be conceived as a strategic investment for sustainable development.

To do this, the connection between business, investors, and natural capital (including, but not limited to, biodiversity) should be made clear: according to the World Economic Forum, almost half of the global gross domestic product (GDP; corresponding to the value of 44 trillion dollars) depends on ecosystem services guaranteed by biodiverse and functional habitats (WEF, 2020) and biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse could lead to a drop in global GDP by $2.7 trillion per year by 2030. Furthermore, the European Commission has estimated that for every euro invested in ecological restoration, there are 8 to 38 euros in return (EC, 2022), which is much more than what is obtained by many standard financial products!

A crucial role is further played by urban areas, where it is more evident that ecological restoration and social justice are sibling issues that could (and should) be simultaneously addressed. Indeed, the United Nations estimated that about 70% of the world population will live in urban contexts by 2050 (UN, 2022) and these are the areas where the 70% of Green House Gas Emissions are originated (ICCP, 2022). In this perspective, it is mandatory to take advantage of the huge efforts produced within the Nature-based Solutions (NbS) strategic area in the last decade, as NbS clearly represent a primary tool for most of the NRL targets, while ensuring human well-being at the same time.

Finally, for the NRL to be effective in a short time, it is essential to have a thorough understanding of the approaches and practices to be followed. Thanks to the foresight of funding strategies in R&I put into action in the last decade by the EU and by other relevant actors, the knowledge about environmental and climatic risks, recovering strategies, and related impact has largely increased. This knowledge should be made available and shared as soon as possible, to drive decision makers.

At a national level, Italy has a huge initiative dedicated to building and sharing knowledge on biodiversity and nature restoration: the National Biodiversity Future Centre, funded by the EU under the NPRR and started in 2022, is the largest project ever funded in Italy on Biodiversity, with more than 320M Euros of investment. More than 2000 researchers are contributing to building the national biodiversity and ecosystem function community, boosting knowledge. One gateway connected to four data platforms and several other products will be made available for society at the end of the project. This would likely drive decision-makers and practitioners toward the most rapid and cost-effective direction.

We have no reasonable alternatives.

Heather Brooks

about the writer

Heather Brooks

Heather Brooks is an urban enthusiast focused on all things related to urban nature, climate, and city soundscapes. She is policy advisor in the environment and climate team at Eurocities. On the recently adopted Nature Restoration Law, she worked with cities, national ministries, MEPs, and NGOs.

The EU Nature Restoration Law is here. Do we have what it takes to make it work?

Yes and no. Firstly, the adoption of the Nature Restoration Law (NRL) is brilliant news for cities, which were very vocal in their support of the urban ecosystem restoration targets. The targets for urban ecosystem restoration include no net loss of urban green space or tree canopy cover by 2030, and thereafter an increasing trend in both until “satisfactory levels” are reached―a level that will need to be defined by national governments with the support of the European Commission. And this is crucial as cities face increasing pressure in terms of how to use land with growing demand for housing, and for transport and energy infrastructure. Land take―by this we mean the conversion of land cover from natural to agricultural and urban use―is a key driver of biodiversity loss, while sealing our soils with concrete increases urban heating as well as surface water runoff and flooding. Cities know this, and that’s why they wanted support to protect and restore existing urban green space.

So, what will it take to implement the NRL on a local level? In the short-term, it means exploring existing policy regulations and building codes that can support greener developments, practices for the protection of mature and healthy trees, and partnerships with businesses that encourage the de-sealing of small portions of their car parks, for example, or tree planting schemes. In the longer term, the NRL provides a framework to guide cities towards more sustainable urban and spatial planning. The targets for “no net loss” do not mean “no development”, they rather acknowledge the crucial benefits of urban green space and tree cover for the health and wellbeing of citizens, and the fight against the triple crises of climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution.

Is that all? In itself, this is no small task, but there’s also a catch. Practically speaking, this requires human and financial resources that cities just do not have. Cities will need technical expertise to design effective nature-based solution projects. Take the example of biosolar roofs which combine green and solar roofs to the benefit of both―green roofs cool the solar panels increasing their efficiency, while the solar panels provide shade to the green roof allowing for a wider range of flora; however, the type and proportion of green roof to solar panel requires specific knowledge that is often lacking within cities. This knowledge is often lacking in the construction sector too. Once the project has been designed, there is the challenge of finding the upfront cost for its implementation. Access to EU-level funding is often long and complicated for cities to apply to. Then add to this the long-term maintenance costs―once the project is complete, who should fund its maintenance needs?

Indeed, financing is a key area that needs focus to ensure the longevity of restoration projects. As part of the NRL, member states will need to develop National Restoration Plans (NRP) highlighting the planned measures, who is responsible for them, and, crucially, how they will be financed. Cities must be equal partners in the discussions as to the selection of measures and financing.

So how can NRPs help us to overcome the financing and human resource gap? By addressing the final key challenge: siloed knowledge and planning. Be it within municipalities or across governance levels (from local to regional to national), one of the greatest―and oldest―threats to restoring nature is siloed working. It’s also one of the greatest opportunities.

Concrete knowledge as to benefits and design of nature restoration projects―from human health, to building the resilience of ecosystems, to reducing air and noise pollution, and more―is often contained within a small subset of staff working in municipalities. As cities increasingly feel the impact of climate change, nature restoration can provide a cost-effective solution to adapting and building the resilience of our cities. But this requires breaking through our silos to plan for and with nature. This means bringing together experts from departments within cities and national governments to understand the ‘need’ and co-benefits of urban greening. National Restoration Plans should be considered in light of climate risk assessments―on the urban scale, how much green space is needed to reduce heat stress, water stress, flooding, etc? Who is most vulnerable? How should we prioritise restoration measures? Public and private funding must follow these priorities.

Finally, the European Commission has just announced the possibility of a new policy on nature-credits, similar to those for carbon (under the Emissions Trading System). For now, we are cautious about this prospect; it is well known that habitat destroyed in one place cannot be replaced in another―not only can we not create the exact ecosystem in a different location, but, purely from a human perspective, we also lose access to that ecosystem for the residents. It is far from clear that nature-credits could be the solution to achieving our nature―and climate―objectives. Rather, re-directing some of the harmful subsidies and uplocking private sector investment via other means, should be the priority.

Marta Mansanet Cánovas and Roby Biwer

about the writer

Marta Mansanet Cánovas

Marta Mansanet is a Policy Officer at the Commission for Environment, Climate change and Energy (ENVE) of the European Committee of the Regions (CoR). Her work focuses on shaping EU policymaking by ensuring that the perspectives of cities and regions are considered on key issues like urban greening, pollinators, nature-based solutions, and local adaptation plans.

about the writer

Roby Biwer

Roby Biwer is the former Mayor and currently councillor of the municipality of Bettembourg, in Luxembourg. He is an active member of the largest Luxembourgish association for the protection of nature and environment (natur&ëmwelt), and since 2013, its national president. Roby Biwer has also been president for 18 years of SICONA.

The EU Nature Restoration Law is here. Do we have what it takes to make it work?

The EU Nature Restoration Law is a monumental step forward for biodiversity, climate and environmental resilience in Europe. As representatives of both, the administrative and political level of the European Committee of the Regions (CoR), we can confidently say that while the ambition and legal framework are solid, the real challenge lies in implementation. Do we have what it takes? The answer is: potentially, but only if we address some key hurdles and maximize the tools at our disposal.

First, let’s acknowledge what the law represents. It’s the first piece of EU legislation to explicitly set legally binding targets for ecosystem restoration across land and sea. It’s a beacon of hope for reversing biodiversity loss and tackling climate change, with the potential to bring back degraded ecosystems, improve pollinator populations, and build resilience to natural disasters like floods and droughts. On the global stage—especially at biodiversity COPs—, the law is a chance to solidify the EU’s credibility as a leader. But setting targets is one thing; achieving them is another.

One of the biggest factors for success will be funding. Nature restoration is not cheap, and local and regional authorities—the backbone of implementation—will need significant financial support. The EU is planning to earmark resources for restoration projects. However, these funds often come with strings attached or require co-financing, which can be a barrier for smaller municipalities. We’ll need to ensure better access to these funds and encourage innovative financing models, like public-private partnerships or green bonds. Ensuring a good distribution and allocation of the resources and attracting private investments will be essential.

Then there’s the issue of local capacity and expertise. The EU’s diversity is one of its strengths, but it also means varying levels of readiness to implement such an ambitious law. Some regions have the expertise, networks, and political will to move quickly, while others are still struggling with basic environmental management. At the CoR we facilitate information, encourage peer learning, share best practices, and provide resources for technical support to regions and cities that might otherwise lag behind.

Stakeholder engagement is another make-or-break factor. Restoration efforts won’t succeed if they’re imposed from the top down. Farmers, fishers, foresters, and local communities need to be part of the process, not just as passive recipients but as active co-creators. They’re the ones who know the land and sea best and will be directly affected by restoration measures. That’s why it’s vital to provide clear benefits for everyone involved—whether it’s financial incentives, improved ecosystem services, or new economic opportunities like eco-tourism.

Of course, we can’t ignore the political and social resistance that may arise. Some sectors view the Nature Restoration Law as a threat to economic activities, particularly agriculture and fisheries. We need to frame restoration not as a cost but as an investment in long-term sustainability. Healthy ecosystems mean more fertile soils, more productive fisheries, and better protection against climate impacts. Nature restoration also means enhanced wellbeing conditions for citizens and provides health benefits. Communicating these messages effectively to everyone is crucial for the success of the law and will require coordinated efforts at all levels of governance.

Next, there’s monitoring and enforcement. The Nature Restoration Law includes clear benchmarks, which is crucial. But tracking progress across the EU is no small feat. We’ll need robust, standardized monitoring systems and transparency in order to hold Member States accountable. This is where local and regional governments can shine. They’re closest to the ground, literally, and can provide invaluable data and insights—if they’re given the resources and tools to do so.

Finally, we would emphasize the need to amplify awareness-raising efforts to engage and sensitize all citizens – well-informed communities can become strong advocates, driving change from bottom up and ensuring long-term support for restoration efforts.

So, do we have what it takes? The foundations are there: strong legislation, EU funding mechanisms, and a network of committed actors. But success will depend on how we fill the gaps: ensuring adequate distribution of funding, building capacity, engaging stakeholders, addressing resistance, and maintaining accountability. The Nature Restoration Law is a once-in-a-generation opportunity to not just stop the decline of Europe’s nature but actively rebuild it. It’s going to be tough, no doubt, but with collaboration and determination, we can make it happen.

Jordi Cortina-Segarra

about the writer

Jordi Cortina-Segarra

Jordi is a Professor of Ecology at the University of Alicante (Spain) and a member of the Board of the Society for Ecological Restoration, he specializes in dryland ecology and restoration. His current research emphasizes participatory systematic restoration planning and vocational education and training (VET).

This law presents a transformative opportunity to halt environmental degradation and improve the well-being of European citizens, but its success depends on addressing several critical challenges. Policymakers must recognize the law’s importance, understand its potential to reverse nature degradation and enhance the quality of life of European citizens, and act with determination to achieve its goals. Equally, there must be a deeper comprehension of what ecological restoration entails. Restoration goes far beyond reforestation, rewilding, or revegetation; it requires a nuanced approach that considers its scope, benefits, and limitations. Effective restoration must be grounded in science, supported by research, rigorous monitoring, accessible information, and comprehensive training. Public engagement is essential, and authorities must create mechanisms to ensure active participation and equitable distribution of restoration benefits.

Coordinated actions and tools to ensure project quality are critical to achieving meaningful results. Governments should facilitate the access to resources like demonstration and pilot projects, best-practice guidelines, standards, and certification systems to maximize benefits, mitigate risks, and attract private investment. To support the law’s ambitious objectives, administrations need to provide robust strategies, legislative frameworks, and financial tools while encouraging local initiatives and promoting integrated, landscape-scale, long-term projects.

Unlike other regulations of its magnitude, this law does not assign responsibility for degradation to specific actors or actions. Instead, it acknowledges centuries of human impact on the environment and emphasizes the collective responsibility to repair it for the benefit of nature and humanity. With over 50% of global GDP—exceeding €40 trillion—dependent on ecosystem services, the importance of restoring nature is undeniable. The law responds to current environmental crises, including climate change, biodiversity loss, and desertification, by setting ambitious targets for affected areas and emphasizing the necessary social and economic efforts. Restoration is not merely an expense but a sound investment, as its benefits far outweigh the costs.

In Mediterranean countries, large-scale restoration represents a dual opportunity: fostering sustainable economic growth while addressing critical socio-ecological challenges. These include adapting to climate change, reducing risks such as wildfires, coastal erosion, and flooding, and tackling rural depopulation. Academia should play a vital role in these efforts by generating and transferring knowledge, developing quality assurance tools, raising awareness, providing training, and fostering meaningful dialogue.

One of the law’s most complex but vital aspects is prioritizing restoration efforts. It provides clear criteria, with some mandatory, such as compliance with European nature directives under Articles 4 and 5 and specific measures for river restoration and reforestation, while others are aspirational, like success indicators for urban ecosystems, agroecosystems, pollinators, rivers, floodplains, and forests. Restoration must balance these overarching objectives with local considerations to achieve maximum impact. For example, addressing large-scale risks like wildfires, coastal erosion, and flooding should be a priority for both national and subnational governments due to their far-reaching effects. At the local level, additional factors, such as the cultural or identity value of natural spaces or alignment with local development strategies, must also be taken into account. Engaging society in this process is crucial.

Ultimately, this law represents an unparalleled opportunity for economic and social development, particularly in rural areas. By prioritizing strategies that align ecological restoration with regional growth, it is possible to strengthen ecosystems and communities simultaneously.

Marta Delas

about the writer

Marta Delas

Marta Delas is a Spanish architect, illustrator, and videomaker. Concerned about urban planning and identity, her artwork engages with local projects and initiatives, giving support to neighbourhood networks. She has been involved in many community building art projects in Madrid, Vienna, Sao Paulo and now Barcelona. Her flashy coloured and fluid shaped language harbours a vindictive spirit, dressed with her experimental rallying cries whenever there is a chance. Together with comics and animations she is now building her own musical universe.

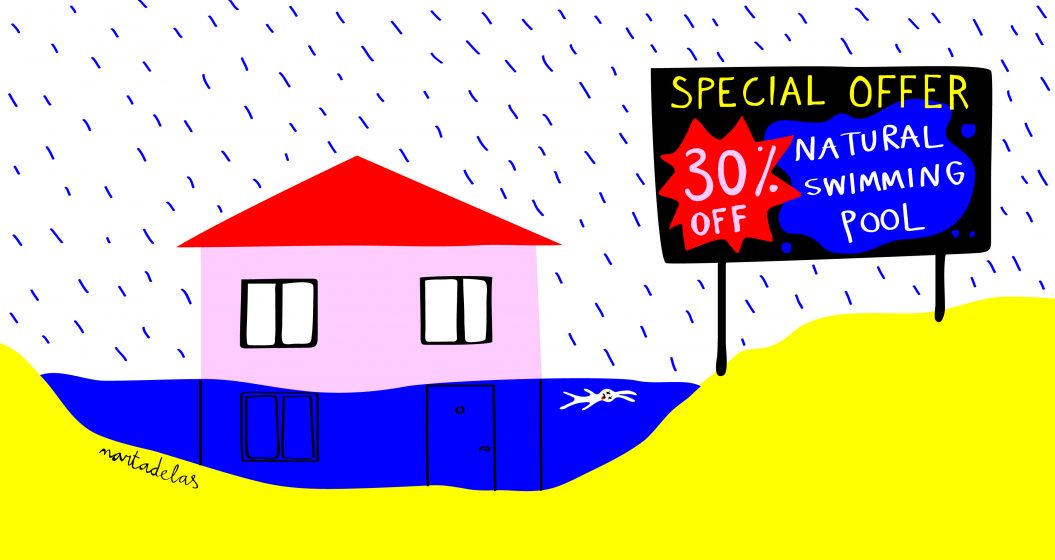

Laws are useful allies when it comes to implementing changes, but without political engagement and citizen support, there is always a risk that the law is misinterpreted, bypassed, or even ignored. The EU NRL is crucial to respond to our environmental challenges, but it may not be enough.

Although there is an increasing awareness of climate and biodiversity issues, it is still something escaping the list of priority topics for many sectors of our society.

Unfortunately, we have recently experienced the devastating effects of torrential rains in Valencia, where many of the houses that were destroyed were actually built in flood-prone areas, and recently updated emergency protocols had been deactivated by the new government, resulting in more than 200 deaths and 130.000 damaged homes.

These recent events have set off alarm bells in the population and have triggered a huge mobilisation and consciousness campaign. This is a huge opportunity to bring the importance of the Nature Restoration Law to the table and discuss the need to pay attention to the natural drainage network, not ignoring its relevance when it comes to planning major infrastructures.

We need to gather information on what has happened, using this evidence as a powerful resource to deliver a message: We cannot afford to ignore nature and the climate crisis we are experiencing. We must act, raise awareness, and listen to experts on the matter. Our governments must include professionals on ecosystem restoration in planning processes, or there will be more and more fatal consequences.

It is crucial to learn from these examples, such as the case in Valencia, keep the media focused on them, and take advantage of the current situation to introduce the NRL to the public. In a world where it is difficult to keep the media focused on an event for more than a few weeks, no matter how catastrophic it may be, it is vital that we take the opportunity of these events to communicate effectively and build a social network that is aware of the law and is, therefore, ready to back it up when it comes to implementing new policies.

If we miss this chance, if we are not able to maintain the public debate around this subject, if this case is not brought to international attention, and if a strong enough debate is not triggered regarding what has happened, we run the risk that the law will become a paper exercise and institutions will prefer to pay exorbitant fines rather than preserving the environment.

João Dinis

about the writer

João Dinis

João Dinis, Cascais’ council climate action director, graduated in Geography and Urban Planning with a post-graduate degrees in Geographic Information Systems and Sustainable Development Strategies. He is currently responsible for Cascais' action strategy for climate change and sustainable development strategies through innovative approaches in spatial planning, technology, green and circular economy, and governance models.

The EU Nature Restoration Law: Cities on the Front Line of Action

What an intriguing task it is to define the “European Union”. There are myriad perspectives, each shaped by personal and political lenses.

To me, the EU embodies the “world’s greatest peace project,” an unprecedented union of nearly 30 countries that once stood apart. What binds us, you ask? I would say, “our common good”.

Indeed, our natural heritage is not only the backbone of this thought but also our future as Europeans.

The EU Nature Restoration Law (NRL) stands as a central pillar of European ambition, leading a systemic approach to sustainable development, ensuring no one is left behind. Local communities and nations are called to join forces under the ambitious European Green Deal.

This new Law’s harmonization for Member States requires a multi-scale approach, tackling various levels of commitment and resources. For the Law to thrive, the European Commission must empower nations with reasonable funding and technical support, fostering a collaborative spirit with regional and local governments. It clearly stands as an opportunity for cities to their communities as agents of change.

By focusing on the local perspective, the NRL embraces the potential of collaboration among stakeholders, citizens, and communities, directly involved in nature restoration practices. It will raise awareness of our ecosystem’s importance for climate resilience, social cohesion, well-being, and a healthy environment, stimulating the green economy and providing a sustainable model for cities and municipalities, aligning perfectly with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

And a significant part of it focuses on the EU’s vision for climate change adaptation. The revised EU’s Climate Change Adaptation Strategy highlights the importance of “nature-based solutions” and “green infrastructure” to mitigate vulnerabilities and risks from extreme weather events. Severe droughts, heat waves, forest fires, health impacts, biodiversity loss, and increased energy demand—these challenges also threaten social inequality within local communities and EU member states. The NRL’s vision is to address these through biodiversity and ecological balance in urban areas, transforming green spaces, water bodies, wetlands, green corridors, forests, coastal areas, cliffs, and many more.

However, the success of this nature-based development approach requires its integration into spatial planning processes. Urban development must benefit from inclusive, resilience-driven policies. The NRL’s foresight can accelerate the uptake and scale-up of these solutions, showcasing cities as successful case studies in combating heat-island effects, reducing flooding hazards, promoting carbon sinks, curbing biodiversity loss, and improving air quality. This will promote sustainable mobility, healthier lifestyles, public health, and more leisure options for residents and visitors, ultimately enhancing quality of life.

EU Member States must develop their own nature conservation plans, but cities can take the lead by adopting similar principles for their ecosystems, spearheading the NRL’s successful implementation. Engaging with local stakeholders, cities can raise awareness and clarify new opportunities for a sustainably driven economy. Cross-sectorial coordination will foster coherent policies benefiting all.

Following Europe’s global leadership in peace-making and sustainability, the law is a landmark where nature takes centre stage in a coordinated international effort to address 21st-century challenges. Climate change, thriving economies, and peaceful communities can only be achieved through collective efforts to safeguard our precious resources.

The NRL can foster thriving communities with a harmonious urban environment and natural ecosystem. The future of cities lies in their ability to adapt to societies’ fast-changing pace and the risks posed by climate change. As older generations brought us peace and prosperity, it is now our turn to do the same for future ones. This time from local to global, leaving no one behind.

Niki Frantzeskaki

about the writer

Niki Frantzeskaki

Niki Frantzeskaki is a Chair Professor in Regional and Metropolitan Governance and Planning at Utrecht University the Netherlands. Her research is centered on the planning and governance of urban nature, urban biodiversity and climate adaptation in cities, focusing on novel approaches such as experimentation, co-creation and collaborative governance.

EU Nature Restoration Law comes to town? Restoring urban riverscapes requires landscape action, collaboration, and imagination

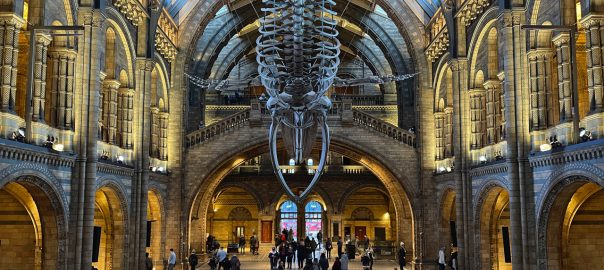

Walking in European cities is oftentimes a walk of discovery. On a recent trip to Catania, Sicily, walking in the city center led me to a fountain that otherwise would have gone unnoticed if a local was not pointing out to me that under the fish market runs an old river with only one “visible point”: the visible point is under the fountain (see Photo 1). In the north-western part of Europe, a celebrated case of urban regeneration involves another canal in the city of Utrecht: where was before a street, a canal has been resurfaced even though it remains disconnected from the waterscape of the city (Photo 2). Such uncovering and “rethinking of the value” of urban rivers require not only a vision from the cities but also a legal push for the importance of regenerating them as parts of broader river landscapes.

The recently enforced European Nature Restoration Law is putting river regeneration to the fore of policy attention. It proposes to restore rivers by removing any type of obstacles to improve biodiversity in riverscapes. This is an important first step in restoring nature, but a landscape perspective is required. That means riverscapes need to also consider the urban riverscape sites in Europe, or to put it simpler: urban riverscapes and urban river deltas need to also contribute to biodiversity, to be restored and renatured. We argued for this as the missing piece in the current law (Frantzeskaki and Malamis, 2024), and a proposal to take on board to seize the potential of urban green and blue spaces to be more than spaces of amenity, to spaces of reconnecting people with nature and connected landscapes with rural areas improving biodiversity. The Nature Restoration Law further shows the importance of urban green spaces and presents a clear target on improving them. What we want to see during its implementation, is the Nature Restoration Law guiding urban green-blue landscapes renaturing and restoration across Europe. That will bring new opportunities for transforming European cities with nature as well as new challenges.

Urban riverscapes have been transforming over time: from trade-water lines in the middle of the Industrial Revolution to waste-disposal areas in late industrialization, to amenity and recreation veins of the cities in the eve of their ecological modernization eras. But not all of them are of the quality to guarantee safe use by humans as well as not designed to contribute to habitat creation for animals, being canalized, with many physical barriers for animals to nest and live in them. Building with and for nature is confronted with many trade-offs: build for people, for nature, or for both? Designing and regenerating urban landscapes for recreation and commercial use does not always allow for habitat creation, deeming to the question: whose benefits get prioritized and whose get compromised? (Stijnen et al 2024).

Restoring urban rivers across Europe to ensure they contribute to nature restoration and become integral parts of the restored European landscape, requires imagination for forward action that connects nature with people and place (Bellato et al 2024). For this we offer three thinking ways forward: First, a landscape perspective is critical, to neither understand nor plan urban river restoration in disconnect from the landscape (river landscape and more) itself. Second, urban river regeneration plans and programs need to be planned in an inclusive and invite interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary teams to consider the various trade-offs that exist and those that will surface with their regeneration, moving to more collaborative ways of planning. Third, employing nature-based solutions to transform urban riverscapes will require radical imagination for the present and the future of our cities, to not have all urban rivers in Europe look alike, to avoid an urban homogenization through design but rather allow for urban riverscape diversity. Let’s start with imagining urban rivers as living veins of our cities full of life and as urban nature.

References:

Bellato, L., Frantzeskaki, N., & Nygaard, C. (Andi). (2024). Towards a regenerative shift in tourism: applying a regenerative conceptual framework toward swimmable urban rivers. Tourism Geographies, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2024.2358306

John Tayleur, Chris McOwen, Opi Outhwaite, and Valerie Kapos

about the writer

John Tayleur

John Tayleur leads the UNEP-WCMC Nature Restored Team to support ecological restoration of degraded lands, inland waters and oceans as the key approach to reverse the global nature crisis. John brings academic, policy, governance, management and communication experience to help the team improve the legal, policy and planning enabling environment, develop monitoring and evaluation frameworks, and provide an accessible knowledge base.

about the writer

Chris McOwen

Chris McOwen, Lead Marine Scientist at UNEP-WCMC, provides strategic and technical oversight for coastal and marine conservation initiatives. His work spans the formation, delivery, and monitoring of national, regional, and global conservation and restoration goals, ensuring alignment with ambitious targets and commitments.

about the writer

Opi Outhwaite

Opi Outhwaite has over 15 years of experience in international and EU environmental law. Her work focuses especially on the intersections of environmental law and policy with trade, agriculture and human rights. Opi is currently Senior Environmental Law Specialist at UNEP-WCMC.

about the writer

Valerie Kapos

Valerie Kapos is Principal Specialist in Nature-based Solutions at the UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre in Cambridge, UK. She helps to oversee and provide strategic direction for the Centre’s work on the role of ecosystems in climate change adaptation and mitigation, and in health and well-being.

EU Nature Restoration Regulation: Opportunities and Challenges in Monitoring Progress

The EU Nature Restoration Regulation (EURR) is a milestone legislation, addressing biodiversity loss, and climate change while emphasizing benefits for people and nature. For the EURR to deliver on its promise, robust monitoring systems are essential to track progress and adjust management practices.

Filling Data Gaps to Meet SMARTER Targets

The EURR contains SMARTER (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-bound, Evaluated, and Revised) targets, which are crucial for driving tangible progress. Setting SMARTER targets requires sufficient data to support implementation and measure progress.

The EURR’s impact assessments revealed significant gaps in the availability and quality of relevant data at the national level, including limited baseline information on the condition of ecosystems and habitats. This presents an implementation challenge for Member States (MS), who must identify areas in need of restoration, accounting for the condition, quality, and quantity of specified habitats. They must also monitor conditions and trends in regulated habitat types and species.

The EUNRR also obliges the European Commission to evaluate the adequacy of National Restoration Plans (NRP) for meeting specific targets and obligations and the Regulation’s overarching objectives. Consistency and availability of data for monitoring and reporting is required to track compliance, effectiveness of national measures, and overall progress towards the headline EU targets.

Monitoring systems must account for social dimensions, including gender equity, safeguarding, and fairness. Comprehensive monitoring frameworks that integrate these considerations will not only meet statutory obligations but also contribute to broader goals of equity and inclusion. This will require intensive data collection and coordinated efforts to improve data quality and sharing.

Synergies

The EURR intersects with existing and proposed EU legislation, including urban planning, energy, agriculture, supply chains, and fisheries. Effective monitoring can support implementation at these intersections, but to enhance efficiency across sectors, objectives will need to be aligned. For instance, leveraging synergies with the European Union Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) could streamline restoration-related monitoring by utilizing and improving forest monitoring and transparency tools being implemented within MS. These tools can also support companies with compliance while reinforcing restoration objectives.

If aligned appropriately, monitoring the EURR can help MS meet their commitments under multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) such as the CBD, UNFCCC, and UNCCD. It can also benefit from global monitoring systems, such as the FAO-led Framework for Ecosystem Restoration Monitoring (FERM) and the Kunming-Montreal GBF monitoring framework. Collaborative initiatives like the Bern process, which facilitates cross-framework cooperation, should be leveraged to develop integrated monitoring systems adhering to international standards. By tapping into global momentum and tools, MS and the EU can accelerate restoration efforts while meeting overlapping global and regional mandates.

Definitions

Whilst the regulation references, for example, degraded ecosystems and implies improvements to structure, function and composition, clear and standardized definitions of key terms, such as “degraded ecosystems” and “area under restoration”, are essential for effective monitoring. These definitions must be harmonized across terrestrial, inland water, coastal, and marine ecosystems to ensure clarity, comparability, and equitable representation. Coastal ecosystems—encompassing seagrasses, kelp forests, and wetlands—must be fully integrated into restoration plans and monitoring frameworks to address gaps in representation.

Capacity

The success of the EURR depends on strengthening the capacity of governments and stakeholders to implement the regulation effectively and monitor progress. Early evidence from the CBD suggests many Parties are not ready to report on target two of the Kunming-Montreal GBF, including headline indicator 2.2, “area under restoration”. Targeted financial and technical support will be essential to develop the systems and data flows required for robust monitoring and reporting. This includes training programs, financial resources, and technical assistance to bridge gaps in expertise and infrastructure.

Collaboration and knowledge exchange are critical to addressing capacity challenges. Sharing best practices, tools, and methodologies among MS and with global counterparts can accelerate progress and foster innovation. Supporting practitioners with practical monitoring tools—such as carbon tracking methods—and ensuring equitable representation of underrepresented ecosystems will be crucial to long-term success.

Gitty Korsuize

about the writer

Gitty Korsuize

Gitty Korsuize works as an independent urban ecologist. She lives in the city of Utrecht. Gitty connects people with nature, nature with people and people with an interest in nature with each other.

In my opinion, the adaption of the Nature Restoration is a big next step on the road to halting biodiversity loss in Europe. Do we have what it takes to make it happen? No. Not yet. Will we find ways to make it happen? Yes. And hopefully soon!

As with all European Directives (the Bird Directive, the Habitat Directive, the Water Framework Directive), it will take time to implement them into national regulations. And even after implementation, it still will take time for organizations, people, and businesses to figure out how they should deal with these new rules. At first, nobody knows the new rules (or they pretend not to know about them). Then the first acts of enforcement are carried out: these projects or incidents (hopefully) will be all over the news. This is the crisis that is needed for change. It will bring the urgency to try harder to figure out the new rules and how to abide by them. And, of course, some people are more interested in figuring out how to legally not abide by them. Thus, showing us the loopholes in the law. On which the law will need to be updated (sooner or later).

All these directives have in common that birds, habitats, water quality, and water management are now incorporated into our governance structures. It’s on the mental map of people who develop projects as topics which they need to take into account. And once they learn the trick of how to deal with the new rules it will become easier. We will learn from each other. We will get inspired by creative ways of incorporating birds, habitats, water, and the restoration of nature into our projects. Eventually, it will become business as usual.

We had an EU Biodiversity Strategy 2010, and an EU Biodiversity Strategy 2020, both with good ambitions, helpful tools, ever-growing monitoring but no legally binding targets. With the new law, we send out a message that we are serious about the restoration of our nature. We are committed to halting biodiversity loss, so committed that we even made a law for it. Not only to restore our nature but also to restore our cities and our (human) future.

By adopting the Nature Restoration Law, we are putting nature higher on the mental map of people. We will be incorporating greening cities into our governance systems. And by doing so, more people will help figure out what it takes to make greener liveable cities happen.

Philipp LaHaela Walter and Goksen Sahin

about the writer

Philipp LaHaela-Walter

Philipp joined ICLEI in 2019 and leads its Biodiversity and Nature-based Solutions Team. He oversees the Team’s current involvement in over 15 projects and initiatives on topics ranging from ecosystem restoration, green and blue infrastructure, nature-positive economy, environmental quality, health to advocacy for biodiversity & NbS on the European and global level.

about the writer

Goksen Sahin

Goksen Sahin is a Senior Advocacy Officer at ICLEI’s European Secretariat, working in Brussels, Belgium. Sahin has extensive experience working in the environmental sector, having previously held roles as: Environmental Projects and Communications Coordinator at Agence Française de Développement; People’s Climate Case Campaign coordinator and Project Manager at Climate Action Network (CAN) Europe; Senior Project Manager and Programme Manager at Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL).

The European Union has taken a monumental step in environmental policy with the adoption of the Nature Restoration Law—the first EU-wide legislation aimed at large-scale ecosystem restoration. With legally binding, time-bound targets for all relevant ecosystems, this law is hailed as a potential game changer in the fight against biodiversity loss and climate change impacts. For our urban areas, it is legally required to ensure that there is no net loss of urban green space and of urban tree canopy cover in urban ecosystems. Yet, some pressing questions emerge: How to design holistic policies to make it happen?

Opportunities for Urban Transformation

Cities are uniquely positioned to spearhead nature restoration efforts. Urban areas, often perceived as concrete jungles, have untapped potential for enhancing biodiversity and ecological resilience. Implementing green roofs, creating urban wetlands, and expanding parklands not only restore habitats but also improve air quality, reduce urban heat islands, and enhance the well-being of residents.

Moreover, the Nature Restoration Law provides a strong impetus for cities to innovate and integrate nature-based solutions into urban planning. Engaging local communities in restoration projects can unlock place-based knowledge, foster a sense of ownership, strengthen the social fabric, and promote environmental education. These approaches are combined into a cohesive framework in the Commission’s Urban Nature Plan initiative, enabling cities holistic urban planning that implements the Nature Restoration Law on the local level.

Challenges on the Urban Front

It would be key to rightly interpret the legislation and design policies. For instance, the questions of: What does “satisfactory level” mean exactly? Are we talking about public and/or private land ownership? Or very simply “Is lawn a green space?” should be answered clearly to design the right policies and integrate them into sustainable urban planning. Especially considering that urban planning, transportation, housing, and environmental protection departments must work cohesively to make this transition happen.

Funding is another critical issue. Restoration projects require substantial investment, and cities may struggle to allocate resources amidst other pressing needs like infrastructure, healthcare, and education. Securing financial support from national governments or the EU as well as mobilising resources from the private sector might go a long way in scaling restoration action.

Bridging Sectoral Divides

One of the pivotal factors in the success of the Nature Restoration Law will be the ability to set aside sectoral divides for joint, effective actions. Collaboration between different levels of governments, as well as with the private sector, NGOs, and the community in a whole-of-society approach is essential. Cities can serve as hubs for such collaborative efforts, fostering partnerships that leverage diverse expertise and resources.

Engaging businesses, for instance, can unlock innovative financing models and technological solutions. Involving youth representatives and community groups can infuse fresh perspectives and drive grassroots support. Such inclusive approaches are packaged in the Urban Nature Plan framework, enhancing the scalability and sustainability of restoration initiatives.

Moving Forward with Urgency

The intertwined climate change and biodiversity loss crises demand urgent and decisive action. For cities, this means not only embracing the opportunities presented by the Nature Restoration Law but also proactively addressing the challenges. Developing comprehensive Urban Nature Plans, securing necessary funding, fostering cross-sector collaboration and building local capacity through programmes such as UrbanByNature are critical steps forward.

As demonstrated by the newly launched global initiative “Berlin Urban Nature Pact”, cities have the potential to become lighthouses of sustainable living, but realizing this vision requires commitment, innovation, the whole―of government approach and financing to transform how we think about urban spaces.

Do we have what it takes to make it happen? The answer lies in our actions today.

Shane McGuinness

about the writer

Shane McGuinness

Dr. Shane Mc Guinness FRGS is a conservation biologist specialising in human-wildlife interactions, conservation finance and wetland restoration. Dr. Mc Guinness is a coordinator of the WaterLANDS project, a Climate Fellow of University College Dublin, a Senior Project Manager with ERINN Innovation, and is the Founder and Director of Peatland Finance Ireland, a not-for-profit which structures blended finance for restoration.

Let’s not downplay the significance: the passing into force of the Nature Restoration Law has been a seismic success which sets strong precedent in global terms. It’s ambitious commitments, though significantly eroded from initial targets, have nevertheless traversed choppy democratic waters and landed safely. This has not been without pain, and is not unanimous, though rarely do such progressive actions reach immediate “normal” status. Notable in this process was the opposition of Member States usually supportive of environmental protection and restoration, exposing the inevitable economic impact expected from the NRL on forestry, peat mining, and agriculture in particular. Notable also was the strong support of Ireland, traditionally averse to measures impacting on the nation’s vital agri-food sector, based on the clearly communicated demonstration that farmers will not be over-burdened or vilified.

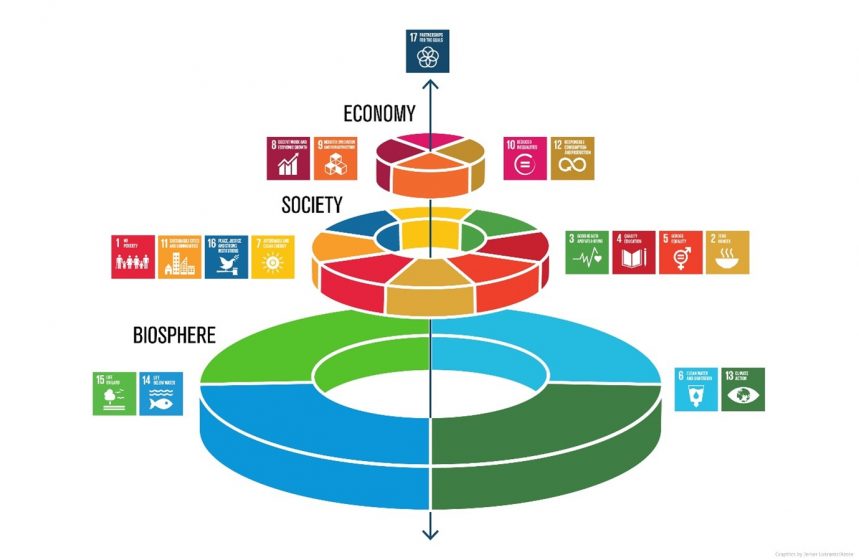

At present, we do not live in a reality where actions are taken of purely moral imperative (especially those of an ecological slant). Rather, we must rely on existing market function, pressures, and drivers to implement change. This includes valuation of the services that nature provides, through either carbon, water, and biodiversity markets, or the emergent development of natural capital accounting. However, like any system relying on collective exploitation of a commons, strict oversight would thus be required, which is where the NRL should enter. And, also, though cross-sectoral support for such a seemingly “niche” Law will remain challenging, this is where objective economic assessment of costs, opportunities, compliance, and obligation will drive action on the NRL mandate above and beyond these commitments. Nature restoration will soon be seen as common-sense, economically, socially, and environmentally, especially if the “wedding cake” for the Sustainable Development Goals is better translated into policy and action.

If the transposition, implementation, and regulation of Directives in the past have taught us anything, it is that we should expect under-compliance and delays. My belief is that if we anticipate this underperformance from the beginning, respectfully engage with and incentivise communities, and appreciate the harsh economic realities of this phase shift in European life, then greater buy-in will be achieved. Inducing steep legal fees and fines for failure to comply does little for long-term support.

If the transposition, implementation, and regulation of Directives in the past have taught us anything, it is that we should expect under-compliance and delays. My belief is that if we anticipate this underperformance from the beginning, respectfully engage with and incentivise communities, and appreciate the harsh economic realities of this phase shift in European life, then greater buy-in will be achieved. Inducing steep legal fees and fines for failure to comply does little for long-term support.

Finally, relying on the separate, seemingly sentient forces of “the market” has yielded great development, scientific progress, and human well-being for centuries. These same forces have also led to inequality, injustice, and great environmental damage. Though often used as a catch-all solution, an embedded shift in mindset from a purely anthropocentric to a pseudo-ecocentric approach is required, allowing the exploitation of free market function for the good of the planet. In the same way that we should see the direct and interdependent coupled crises of biodiversity loss and climate change, we should also see the essential role of focussed education and outreach initiatives around nature and climate. This should be seen as a crisis on the same level as the COVID-19 pandemic, the depletion of the ozone layer, or the action that the climate crisis should be generating.

Despite the setbacks and dilution, I am confident that this is a non-return point for nature, if with a certain level of hysteresis or lag. Ensuring that national representative bodies have adequate resourcing, legitimacy, and creative freedom to support such efforts is thus ever more pressing.

Anne-Sophie Mulier

about the writer

Anne-Sophie Mulier

Anne-Sophie Mulier is a bio-science engineer and works as a project and policy officer in Brussels. Her work relates to the sustainable management of rural areas in Europe. During several years she coordinated the European secretariat for engagement and recognition of landowners in nature conservation efforts at the European Landowners' Organization (ELO).

In a recent meeting I attended, a “before-after” photo of the same area was shown. It was the result of a successful nature restoration project. What once was a heavily farmed, intensive agricultural area was transformed into a mosaic of diverse extensive land uses. In a room with practitioners, landowners, and conservationists several hands went up. They all had the same question; “How did you convince the landowners and farmers to lower the value of their land from production to nature?”. Because the higher the intensity of agricultural production, the higher the value of the land. And here we are, in need of a serious mind change.

For decades we have been trapped in the dichotomy of “intensive production vs. strict conservation”. Today climate change is more than ever forcing us to rethink. We need our landscapes to produce food, fight climate change, preserve biodiversity, and reduce pollution all at once, and all of crucial value. Intensive agriculture provides us with food, nature can provide us with clean air, water filtration, flood protection, carbon storage, wood, temperature regulation, recreational spaces to walk and play in… Can we see these nature services as “products” in the same way we treat food as a marketable product? Just as we choose which crops to grow, we could think about which services to provide and manage the land accordingly. Similarly, those who produce food get compensated, so why not support those who provide such essential services? Several good examples of this principle of “payments for ecosystem services” already exist in Europe and have much room for upscaling and improvement. Only by generating viable alternative income streams for the benefit of our green environment will it be possible to reach our restoration targets in the long term, for those who want to make the transition to do so, and for those relying on the land to survive.

With the law in place, we must also recognize that quantitative targets, though well-intentioned, may not always be the best way to aim for nature improvement. Qualitative results and the initiative of those living and working on the land are far more valuable than striving for unattainable quantitative targets that will undermine trust in the process.

Nature restoration is not about reverting to a past that no longer exists; it’s about moving forward in a way that benefits both people and the planet. We now urgently need innovative, viable initiatives to make this happen. We need to be ambitious, but we also need everyone on board. Let’s start with “good is good enough”, and take-off from there.

Christos Papachristou

about the writer

Christos Papachristou

Christos is the delegate for Ireland to IFLA Europe. He has landscape architectural and horticultural experience working in Ireland, the UK and internationally. He is a Corporate member of the Irish Landscape Institute and a Chartered Member of the UK Landscape Institute. He lectured in UCD on LVIA and tutored on ornamental wildflower meadow establishment.

This article was sent on behalf of IFLA Europe.

The experience from the implementation of the EU Biodiversity Strategy indicated that while progress was made, over 80% of Europe’s habitats still require significant improvement. The obstacles were clear: economic trade-offs, financial limitations, administrative fragmentation, and varying levels of commitment across Member States. It is this experience that can guide the smooth implementation of the NRL.

One of the key lessons from previous initiatives is the importance of translating policy into practical, relatable terms for both citizens and professionals. The NRL’s targets span ecosystems from forests and rivers to urban spaces, and clarity in communication is essential for fostering widespread support and understanding. Educating the public on the importance of these goals can engage communities in restoration efforts, participation in local conservation projects, and hands-on enhancement of green spaces in cities.

Effective communication is at the heart of successful policy implementation. For the NRL to reach its full potential, it must be supported by timely, clear messaging that informs the public and professionals of practical actions they can take. Digital tools, social media, and local events can be used to disseminate information. Highlighting success stories and showcasing community involvement can create a shared sense of purpose. Direct, in-person interaction remains invaluable, particularly in remote areas where digital reach may be limited. Ensuring that the information is consistent and that communication channels are open, can bolster public trust and maintain momentum.

With these in mind, IFLA Europe has highlighted how landscape architects are uniquely positioned to lead the practical implementation of the NRL. Their training in sustainable design, ecological restoration, and public engagement equips them with the ability to translate policy into easy to understand and implement principles that resonate with the public. What is more, IFLA Europe’s 2024 resolution, has recognised the profession’s deep roots in nature and its critical role in addressing environmental challenges, highlighting their capacity to act as intermediaries between policymakers and the communities.

By incorporating landscape architects in the implementation process, the EU can accelerate efforts in urban greening, rehabilitating degraded lands, and creating infrastructure that supports biodiversity. Their ability to design with both ecological and human needs in mind fosters solutions that are sustainable and publicly embraced. Acting as ambassadors for the NRL, landscape architects can advocate for and demonstrate the tangible benefits of restoration projects, helping to build public confidence and enthusiasm.

The Nature Restoration Law represents a significant step forward for the EU’s environmental policy, promising substantial benefits if implemented effectively. Success will depend on overcoming past challenges, making the message clearer, approachable, and relatable to its communities. The active involvement of skilled professionals like landscape architects can play a pivotal role in bringing the NRL’s vision to life, turning policy into projects that inspire and engage communities. By learning from past efforts and using professional experts to communicate the information and foster a sense of collective responsibility, the EU can smoothly progress toward a more resilient and biodiverse future.

Silvia Quarta

about the writer

Silvia Quarta

Silvia is a drylands restoration practitioner and trainer. Born in the north of Italy, her home is in the dry, arid and wild south of Spain. She is currently involved in the Quipar Watershed restoration project, aimed at restoring 30,000 ha of land around La Junquera. Her role is creating spaces for people in the territory to reconnect with the landscape and foster a culture of care and restoration.

It’s going to take so much effort to achieve these goals, and we’re not ready for it.

At La Junquera, a 1100 ha regenerative farm in the south of Spain (Murcia), we’re at the forefront of regeneration, we’re considered experts, a lighthouse farm, a shining example of regeneration in the region. And we’re doing so little compared to what needs to be done.

So, I fear: where are the experts that can support this shift in land management? A shift in the way we care for nature, we look at nature, we connect to it?

The targets of the EU restoration Law sound beautiful and very much needed. But Europe is not ready for it.

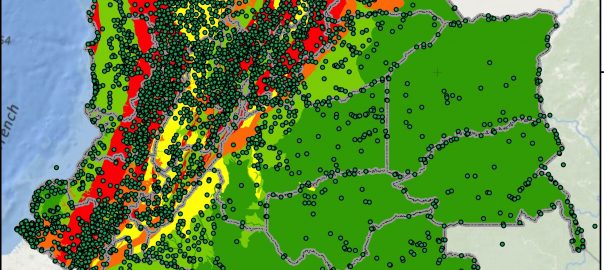

Within the La Junquera team, we’re currently promoting a participatory process to restore the Quipar River Watershed. We’re located at the head of an 80 km long river, which over the past 20 years has suffered over-exploitation, contamination, and reduced recharge due to aquifer exploitation. His banks have not been respected, and the natural vegetation supposed to grow around it (to act as a buffer with intense rain events) has been destroyed, even if we find ourselves in an area of ecological interest. In some areas the river fully disappears. All of a sudden, the reeds and riparian vegetation are suffocated, and instead, you find a perfectly ploughed naked field with almond trees. Or, even worse, intensive plantations of lettuce and broccoli.

Laws have not been respected. Nature is not being respected.

I have no doubt that something will change, but I also have no doubt that the targets won’t be reached, and this will be simply a small push, not enough for the urgency we’re in.

I am glad the European Union is putting this forward, but I believe we need much more than this. Many more things in our current system need to change in order to make the EU Restoration Law a reality. Our current educational and economic systems need to change, in order to prepare ourselves for a very different future, not based on exploitation but on cooperation.

I see the violence with which land is “taken care of” by all of us, and I fear the implementation of these new practices will follow the same frame of structural violence and control over nature.

We need to start feeling part of nature, and working with it, rather than controlling it, for the good or the bad.

As much as I am glad this Law has come through, I very much believe in bottom-up processes, coming from the people who live on the land and care for it and will push from within for a change in practices. Because soon, there won’t be any alternative.

Federica Risi and Martin Grisel

about the writer

Federica Risi

Federica is an interdisciplinary practitioner and facilitator of change who believes in the power of co-creation and sees urban development as a key entry point to unpack and heal society’s relationship with nature. Federica has 8+ years of experience working at the interface between policy, research, and practice, focusing her work around urban sustainability transitions and nature-based solutions.

about the writer

Martin Grisel

What really drives Martin is working with a wide variety of stakeholders, sometimes at a high strategic level, to develop policies and research projects that contribute to greener, more just and yet prosperous cities. As founding director of the European Urban Knowledge Network (EUKN), a network of national ministries responsible for urban matters, Martin operates as a knowledge broker, a connector, a networker, and a strategic advisor and trusted partner of policymakers from the local to the global level.

Federica Risi

Senior Policy and Project officer, EUKN

“Frameworks and roadmaps are only as effective as the belief systems they are made with and the action that is taken from that…”.