The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) estimates that 19 to 23 million tonnes of plastic waste end up in lakes, rivers, and seas annually[1]. This staggering number highlights the urgent need to tackle plastic pollution. The growing production of waste, inadequate disposal methods, and the slow degradation of plastics significantly contribute to the accumulation of litter in aquatic environments[2]. With plastic production on the rise, if current practices continue, mismanaged plastic waste is projected to triple by 2060[3].

European policymakers are intensifying efforts to tackle plastic pollution. The European Union has introduced various regulations aimed at reducing plastic waste and promoting recycling. These measures are part of a broader sustainability commitment, aligning with initiatives such as the European Green Deal, the Circular Economy Action Plan, and the Biodiversity Strategy for 2030.

The problem of microplastics

A growing concern is the breakdown of macroplastics into microplastics (plastics smaller than 5 mm), which can also result from various human products and activities[4]. There are significant worries about the persistence, ubiquity, and irreversibility of microplastics in the environment[5]. In aquatic ecosystems, organisms may ingest microplastics, leading to malnutrition, toxicity, and increased exposure to other contaminants[6][7][8]. These microplastics can accumulate in the food chain, transferring harmful chemicals[9]. Laboratory studies indicate that microplastics can damage human cells, potentially causing allergic reactions and cell death. However, there is still a lack of large-scale epidemiological studies documenting the direct impacts on human health[10].

Recent findings show that about 1000 rivers worldwide significantly contribute to the annual input of plastics into the oceans[11]. Additionally, much of the mismanaged plastics remains near rivers, never reaching the open sea. Once in rivers and oceans, retrieving all plastic waste becomes nearly impossible. While mechanical systems can collect larger plastic items in inland waters, recovery becomes much more difficult once these plastics break down into microplastics.

The key to combating plastic pollution lies in preventing plastic waste from entering rivers and seas. This can be achieved through better waste management systems, recycling, designing products with longer lifespans, and crucially, increasing awareness and environmental education.

Tackling Plastic Pollution: Initiatives at Landscape Laboratory

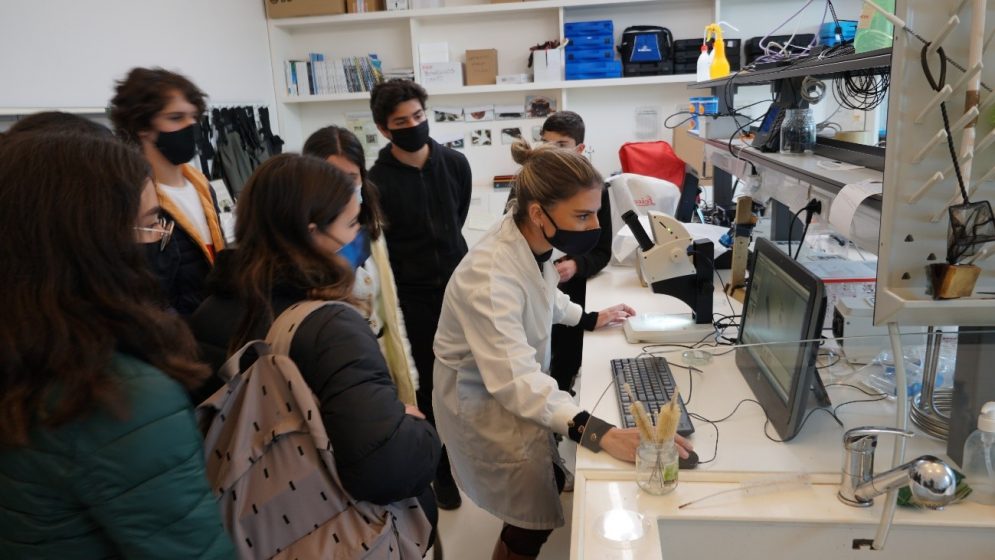

At Landscape Laboratory[12], an association dedicated to promoting sustainable development in Guimarães (Portugal), we are committed to combating plastic pollution in rivers through interdisciplinary projects. Our approach combines advanced research with environmental education, reflecting our dedication to ecosystem preservation.

Our main initiatives include assessing the presence and abundance of microplastics in sediments and aquatic organisms in local rivers, such as the Selho River and the Costa-Couros Stream[13]. Additionally, we aim to educate citizens about the origins and effects of microplastics in freshwater ecosystems. Monitoring these ecosystems and engaging the community are crucial for the successful implementation of mitigation and remediation strategies.

We found that microplastic contamination is widespread in the sediments and aquatic organisms of Guimarães’ rivers, with urbanization being the main driver[14]. These findings have been used in awareness activities to increase citizens’ knowledge about microplastics and their threats to the environment, human health, and the economy.

Using empirical data from 14 sites across two rivers in Guimarães (Ave and Selho rivers), we improved our ability to predict the spatial distribution of litter along the rivers (14). We discovered that the highest accumulation of litter is strongly linked to population density, especially after flood events. These insights are crucial for environmental managers to detect and predict critical litter accumulation points, enabling the implementation of effective prevention and cleanup campaigns.

In response to these findings, the Cleanup4Guimarães project was launched as part of the European REMEDIES program, which supports the EU Mission “Restore our Ocean and Waters”. This mission aims to protect and restore the health of our oceans and waters through research, innovation, citizen engagement, and blue investments. The project fosters collaboration between the Municipality of Guimarães, Landscape Laboratory, the University of Minho, The Centre of Molecular and Environmental Biology, and local citizens to clean waterways and repurpose collected plastic. Activities include mobilizing volunteers to remove river waste, installing floating litter retention barriers, and recycling the gathered plastic. This strategic partnership will identify critical areas of plastic pollution and take effective action.

In August, Guimarães will launch an awareness campaign to highlight the importance of keeping rivers free of plastic. The campaign will include an exhibition in Largo do Toural, the heart of the city, showcasing images of recently collected plastic waste. This exhibition aims to engage the community and promote a shift towards circular economy. Additionally, an art installation at the Landscape Laboratory building will draw attention to the critical issue of plastic pollution in our rivers, which serve as major pathways for microplastic residues traveling from land to the oceans. Beyond raising awareness, the campaign will focus on action: the collected plastics will be sorted, analyzed, and recycled.

Guimarães, aiming for climate neutrality by 2030, recognizes that tackling plastic pollution is crucial for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and preserving marine ecosystems that sequester carbon. As a finalist for the European Green Capital 2026, the Guimarães reaffirms its commitment to sustainability. Reducing plastic use, developing waste management technologies, and raising public awareness are essential to tackling plastic pollution and protecting the planet.

Ana Pinheira and Carolina Rodrigues

Guimarães, Guimarães

about the writer

Carolina Rodrigues

Scientific Coordinator at the Landscape Laboratory (Guimarães), an institution dedicated to Environmental Research and Education. Co-chair of the “Green Areas and Biodiversity” working group within the EUROCITIES network since 2019. Was part of the writing team for the winning proposal for Guimarães as the European Green Capital 2026.

References

[1] https://www.un.org/en/observances/environment-day

[2] van Emmerik, T.H.M.; Gonzalez-Fernandez, D.; Laufkotter, C.; Bletter, M.; Lusher, A.; Hurley, R.; Ryan, P.G. (2023). Focus on plastics from land to aquatic ecosystems. Environmental Research Letters, 18, 040401.

[3] Lebreton, L.; Andrady, A. (2019). Future scenarios of global plastic waste generation and disposal. Palgrave Communications 5, 6.

[4] Frias, J.P.G.L.; Nash, R. (2019). Microplastics: finding a consensus on the definition. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 138:145-7.

[5] Villarrubia-gómez, P.; Cornell, S.E.; Fabres, J. (2018). Marine plastic pollution as a planetary boundary threat – the drifting piece in the sustainability puzzle (2018). Marine Policy, 96:213–20.

[6] Andrady, A.L. (2017). The plastic in microplastics: A review. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 119, 12–22.

[7] Luís, L.G.; Ferreira, P.; Fonte, E.; Oliveira, M.; Guilhermino, L. (2015). Does the presence of microplastics influence the acute toxicity of chromium (VI) to early juveniles of the common goby (Pomatoschistus microps)? A study with juveniles from two wild estuarine populations. Aquatic Toxicology, 164, 163–174.

[8] Santana, M.F.M.; Moreira, F.T.; Turra, A. (2017). Trophic transference of microplastics under a low exposure scenario: Insights on the likelihood of particle cascading along marine food-webs. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 121, 154–159.

[9] Teuten, E.L.; Saquing, J.M.; Knappe, D.R.U.; Barlaz, M.A.; Jonsson, S.; Björn, A.; Rowland, S.J.; Thompson, R.C.; Galloway, T.S.; Yamashita, R.; et al. (2009). Transport and release of chemicals from plastics to the environment and to wildlife. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 364, 2027–2045.

[10] Danopoulos, E.; Twiddy, M.; West, R.; Rotchell, J.M. (2022). A rapid review and meta-regression analyses of the toxicological impacts of microplastic exposure in human cells. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 427, 127861.

[11] Meijer, L.J.J.; van Emmerik, T.; van der Ent, R.; Schmidt, C.; Lebreton, L. (2021). More than 1000 rivers account for 80% of global riverine plastic emissions into the ocean. Science Advances, 7, eaaz5803.

[13] Ribeiro, A.; Gravato, C.; Cardoso, J.; Ribeiro, C.A.; Vieira, M.N.; Rodrigues, C. (2022). Microplastic Contamination and Ecological Status of Freshwater Ecosystems: A Case Study in Two Northern Portuguese Rivers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 15956.

[14] Pace G.; Lourenço, L.; Ribeiro, C.A.; Rodrigues, C.; Pascoal, C.; Cássio, F. (2024). Spatial accumulation of flood-driven riverside litter in two Northern Atlantic Rivers. Environmental Pollution, 345, 123528.

Add a Comment

Join our conversation