As our interviews highlight, the employment scheme has helped to address a range of environmental issues at the household and community level, including income, water scarcity, and food security.

There is a close relationship between the three Es―economy, employment, and environment. Economic growth and jobs rely heavily on environmental resources, but a myopic focus on either of these aspects often results in environmental degradation.

Green jobs have been seen as a way to buffer the adverse effects of economic development on the environment (ILO 2018). The International Labour Organization defines green jobs as those that contribute to preserving and restoring the environment whether in traditional manufacturing sectors or in emerging areas such as renewable energy. Green jobs are anticipated to contribute to the protection of natural resources and enable climate change adaptation.

One of the biggest challenges, especially for the urbanising Global South is finding synergies between the three Es—keeping in mind the persisting inequality in cities. India is perceived as an economic powerhouse, and today is also the world’s most populous nation. The country is rapidly urbanising, with more than 50 percent of its population expected to live in cities by the year 2050 (Ritchie et al., 2024). At the same time, urban India is characterised by considerable inequality and increasing levels of unemployment. Indian cities are also exposed to a range of environmental and climate-related stresses (Rangawala et al., 2024).

In this context, the Ayyankali Urban Employment Guarantees Scheme (AUEGS) of the Government of Kerala, in southern India, assumes significance. AUEGS was initiated by the Government of Kerala in 2011. The scheme aims to provide benefits for beneficiaries as well as to address environmental challenges.

Between May and October 2022, we interviewed 49 beneficiaries employed in the scheme, as well as community members and officials, to document the environmental activities conducted in the scheme and to understand the perceptions of these three groups. Our broader objective was to assess the potential of the scheme in addressing the three Es.

Addressing environmental issues

Several activities were undertaken on private, leased, and public lands. Public lands included premises of government schools, anganwadis (childcare centres), colleges, canals and ponds, and roadsides. Three areas stood out for the interlinked ecological and social benefits for individual households and the community in the context of urban natural resource management—water conservation, urban agriculture, and urban afforestation.

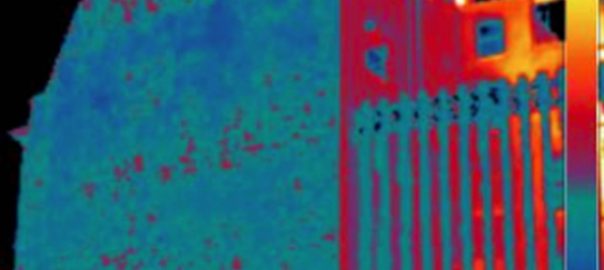

Water conservation activities ranged from digging rain pits and wells in homes to cleaning and desilting public ponds and canals. Digging wells and recharge pits in homes addressed household and domestic water scarcity, especially that of drinking water. Cleaning ponds and canals helped in desiltation and ensured the flow of water, reducing urban flooding. In the aftermath of the devastating 2018 floods that Kerala had witnessed, the state recognised the importance of keeping its waterways clean.

Urban agriculture included flower and vegetable cultivation, and work in coconut (Cocos nucifera) or arecanut (Areca catechu) plantations. This was done on public, leased, and private lands. In public and leased lands, different arrangements were used. In some cases, workers took a share of the produce. In other cases, workers took a share of the produce home and sold the surplus. They shared the income generated from selling the produce, in addition to collecting wages for their work. The scheme also provided labour for agriculture in private lands, to undertake work such as cleaning the land and building bunds for sowing seeds. This was especially useful for poorer agricultural families who could not afford to hire labour to work in their fields. In addition, one family mentioned that they had got an aquaculture pond dug in their land under the AUEGS scheme, using this for fish cultivation.

Urban afforestation involved the planting of fruit and flowering trees on green islands on public lands, in schools and colleges, and on private land. Ornamental plants, including flowering plants, were planted along the side of the road. Species of fruit trees were planted on public land, including mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana) in households; bananas (Musa sp.), amla (Phyllanthus emblica), and jamun (Syzygium cumini) in anganwadis and schools; and cashew (Anacardium occidentale) on public lands.

In addition, other environment-associated activities included the creation of compost pits, cleaning of playgrounds in schools, especially in the aftermath of COVID-19, lopping tree branches, and collecting plastic waste. Cleaning roads by cutting grass was one of the activities people considered especially useful work because it kept the roads free of places where snakes might hide, reducing the risk for people, especially children.

Helping the most vulnerable with accessing jobs

Bureaucrats implementing the scheme described a number of benefits—employment generation, asset creation, women’s empowerment, providing aid to underprivileged and economically poor households, providing social security for the elderly, poverty reduction, and environmental conservation.

Those employed in wage labour were some of the most vulnerable. Several were elderly, some as old as 70 years. They either lacked financial support or wanted to retain their independence, but because of their age, they were unable to work in more physically demanding traditional daily wage work that pays more. In the words of a 72-year-old worker:

“I used to work in paddy fields. If there was no work there I used to go for manual labour. I have physical ailments so doing that work is not possible. Now I only like this work.”

Women also chose to work in the scheme because they could select work near their homes, enabling them to take their young children to the work site. The scheme afforded them the independence to choose the number of days they could work. As one of the women mentioned:

“Unlike other jobs, I can work near my home–this gives me the time to take care of family, do daily chores and then leave for work. In private jobs like saleswoman, I will have to leave very early and also travel a long distance to work.”

For others, this was the only job they could get as they felt they did not have any skills.

Benefits beyond wage earning

The scheme gave preference to households below the poverty line, including those with small land holdings of around 0.01 acres. A poor household could apply for a well to be dug in their home, and at the same time also earn money by having family members employed under the scheme. Thus, they benefited both as community members and as beneficiaries of the scheme.

When we asked the beneficiaries and community members what they most preferred in terms of work, many mentioned agriculture. By growing vegetables that they could take home, they improved nutrition and mitigated food insecurity. They also earned an income from this scheme, especially from selling flowers grown for festivals. Vegetables were grown organically, and people recognised the benefits. As one of the interviewees put it:

“Vegetable farming is a good initiative. The vegetables we buy from the market contains toxic chemicals and consuming them is not good for health.”

They also found agricultural work to be more satisfying. In the words of one of the interviewees:

“I am willing to do any work, but I like agriculture. It gives me happiness when I see the vegetables growing, and they are so fresh and free of pesticide.”

One woman felt that she had learnt a new skill by working in agriculture. Others approved of the urban afforestation that involved planting fruit trees. Even though they would not be able to harvest any fruits immediately, they looked forward to doing so in the future. People also anticipated the shade that the trees would provide. As one of them said,

“I prefer shade trees in the roadside. In the harsh summers it gives shade for pedestrians to walk comfortably.”

The many benefits of the scheme for the individual and the community were not lost on the people. As one of the community members on whose land a well was dug said:

“Thanks to this scheme, I now have a well that will benefit not only myself but also my neighbours.”

For the workers these wages were a critical source of income. Some community members felt that the major beneficiaries were the workers employed in the scheme, especially the aged, as they were able to get work. But there were others who felt differently. As one community member who had a well dug in his house said:

“We are the ones who got a well from the scheme, so we are the ones who get the benefit the most.”

Some also pointed out that the scheme was mutually beneficial:

“Considering the fact that the works make our place clean I guess it is a benefit for me and others who reside here. This makes us happy. For the workers, even if they are old, they have a job and guaranteed living, and as they are doing it in a group it is entertaining and fun for them.”

Conclusions

It is often very difficult to find synergies in tackling economic and environmental challenges, especially those faced by the poor in the fast-growing cities of the Global South. The south Indian state of Kerala’s urban employment guarantee scheme, AUEGS, demonstrates that such synergies are possible. As our interviews highlight, the scheme has helped to address a range of environmental issues at the household and community level, including water scarcity and food security. Urban afforestation provides shade, fruit, and other multiple ecological benefits. The AUEGS also helps to provide the most vulnerable residents—those below the poverty line, the aged, and mothers—dignified employment, and a source of income. Of course, the scheme is not without its issues. For example, workers would like higher wages and more days of work. But in a world where growth is a necessity, dignified employment is a pressing need to address poverty, and protecting the environment for future generations is the need of the hour, schemes such as the AUEGS provide just such an opportunity—to attempt to have it all.

Seema Mundoli and Harini Nagendra

Bengaluru

On The Nature of Cities

about the writer

Seema Mundoli

Seema Mundoli is an Assistant Professor at Azim Premji University, Bengaluru. Her recent co-authored books (with Harini Nagendra) include, “Cities and Canopies: Trees in Indian Cities” (Penguin India, 2019), “Shades of Blue: Connecting the Drops in India’s Cities” (Penguin India, 2023) and the illustrated children’s book “So Many Leaves” (Pratham Books, 2020).

about the writer

Harini Nagendra

Harini Nagendra is a Professor of Sustainability at Azim Premji University, Bangalore, India. She uses social and ecological approaches to examine the factors shaping the sustainability of forests and cities in the south Asian context. Her books include “Cities and Canopies: Trees of Indian Cities” and “Shades of Blue: Connecting the Drops in India’s Cities” (Penguin India, 2023) (with Seema Mundoli), and “The Bangalore Detectives Club” historical mystery series set in 1920s colonial India.

Acknowledgements

We thank Greeshma Saju who conducted the field interviews and are grateful to all interviewees for their time and inputs. We thank Azim Premji University for funding this research.

References

ILO. 2018. Greening with jobs: World Employment Social outlook 2018. International Labour Office, Geneva

Rangwala, L., Chatterjee, S., Agarwal, A., Khanna, B., Shetty, B., Palanichamy, R. B., Uri, I., and Ramesh, A. 2024. Climate Resilient Cities: Assessing Differential Vulnerability to Climate Hazards in Urban India. Report. New Delhi: WRI India.

Ritchie, H., Samborska, V., and Roser, M. 2024. Urbanization. Our World in Data. URL: https://ourworldindata.org/urbanization (last accessed 21st October 2024).

Strietska-Ilina, O., Hofmann, C., Durán Haro, M., and Jeon, S. 2011. Skills for green jobs. A global view. Synthesis report based on 21 country studies. International Labour Office, Skills and Employability Department, Job Creation and Enterprise Development Department, Geneva.

Leave a Reply