Spring in Brussels. Balmy weather, traffic jams, helicopters hovering in skies of pale, duck-egg blue. Politicians, policy-makers and lobbyists rub shoulders with the G4S security personnel tasked with their safety. The guards outnumber their charges, and by some margin. The hotels and train stations are full. Lufthansa is on strike.

At the tail-end of the 4th EU-Africa Summit, April 2014, some forty-odd people have gathered to talk about — and to imagine — the African city of the future. It’s a bold move on the part of the organisers to bring together at least four distinct groups: academics; architects/planners; artists and politicians to swap ideas, share experiences and collectively imagine a better, brighter future for the continent’s beleaguered urban centres. In the organisers’ own words, ‘the objective of the meeting is to define priority interventions that need to occur in cities in order to contribute to a more sustainable, inclusive and creative urban environment, based on cities’ architectural, cultural and spatial capital. How can cultural, architectural and spatial capital contribute to social cohesion and inclusiveness, and to economic prosperity in African cities?’

Over several hours of intense discussion, a broad range of ideas and issues emerged, for the most part centred around those old ‘staples’: education, infrastructure, funding, policy. But, every now and then, a word or a sentence – a description of a park, an open green space, the village square, a desire? – emerged and although ‘ecology’ as a distinct category wasn’t a specific topic on the agenda, two things struck me again and again as I attempted to moderate the discussions: one, that the question of the nature of African cities is still very much up for grabs and two, possibly more interesting, that the culture, history and role of nature in African cities is hardly ever discussed. In and of, of and in. Two sides of the same, particular coin.

Over several hours of intense discussion, a broad range of ideas and issues emerged, for the most part centred around those old ‘staples’: education, infrastructure, funding, policy. But, every now and then, a word or a sentence – a description of a park, an open green space, the village square, a desire? – emerged and although ‘ecology’ as a distinct category wasn’t a specific topic on the agenda, two things struck me again and again as I attempted to moderate the discussions: one, that the question of the nature of African cities is still very much up for grabs and two, possibly more interesting, that the culture, history and role of nature in African cities is hardly ever discussed. In and of, of and in. Two sides of the same, particular coin.

Note: The ‘Sweet’ in the title refers to the West African colloquialism, ‘sweet, paa,’ meaning ‘deep’, ‘profound’, ‘meaningful’.

Root(s)

The word ‘root’ has multiple and myriad meanings. Amongst those that are of interest (or relevance) to me, are:

- (noun) the essential, fundamental or primary part or nature of something (your analysis strikes at the root of the problem);

- (noun) origin or derivation, especially as a source of growth, vitality or existence (plural) a person’s sense of belonging in a community, place, especially the one in which he/she was born, brought up;

- (noun) an ancestor or antecedent;

- (verb) to take root: to put forth a root, to establish and begin to grow;

- (verb) to take root: also to become embedded or effective;

- (adverb) entirely; completely; utterly; radical; complete.

In the sense of 2) and 3) above, origins and ancestors, the following short story perfectly encapsulates a now almost forgotten sense of the importance of nature in Accra, the capital city of Ghana, West Africa.

‘As a child, I knew how far I could stray outside our family compound by the trees. That tree, yes, that one . . . I don’t know how you call it. In our language, it’s called awiemfosamina. That tree, they plant it at the edges, the edges of properties. So, you see . . . when you go roaming as a child, when you see that tree, you know you are at the edge of something, maybe your family’s compound, maybe somebody else’s property, maybe the edge of the area. That tree is a signal, a sign. Yes, a sign.’

— © Lesley Lokko, PhD Dissertation, 2007, Out of Africa: Race, Space, Place.

Its crown is umbrella-shaped and can reach heights of up to 45 metres. Both fresh leaves and fruits are reddish in colour, hence the name albizia ferruginea, referring to the Latin word for ‘iron’, or ‘rust-coloured’. The wood is moderately durable, resistant to fungi and termite attacks. It is suitable for building construction, carpentry and railroads, but also for toys, furniture and musical instruments. Its leaves can be eaten by goats. Parts of the tree are used to treat dysentery.

A tree that marks an edge. Amongst many other things.

Awiemfosamina’s pods also be cracked open, boiled and applied to mud walls as a sealant, keeping the natural iron-coloured pigment intact.

In our conversations in Brussels last week, we seldom mentioned the words ‘material’ or ‘matter’, as though the stuff of our cities matters less than its form. Yet the relationship in most tropical climes between the natural and the manmade (for want of better terms), is profound: heat and humidity combine to ensure a fecundity that is fierce, almost fearful. Inert matter — concrete, glass, metal, wood — must fight nature in order to survive, maintain, remain. Things rot, disintegrate, weather and decay at a rate that far exceeds anything more milder climes contend with. Nature’s vitality is evident everywhere. Yet we speak little of nature, even less about it. It seems to me that there’s a missed opportunity somewhere to think deeply and creatively about what nature means to us, and to translate those narratives into built/grown/planted/managed form. The program of a park (recreation, respite, respiration) might be one such example but I suspect (hope) there are others. In a context and culture(s) where the very term ‘nature’ and the word ‘natural’ might have radically (see 6 above) different meanings, the opportunity to come up with new programs, new forms, new landscapes of leisure and pleasure is perhaps more visionary than we’ve been prepared to accept.

Radi(c)al City

Similarly, although speaking to and with a different audience (students rather than politicians) ‘ecology’ and ‘nature’ aren’t specific topics on the list at many schools of architecture — much less African schools of architecture — but in my present role as coordinator of final year (Masters-level) students at the University of Johannesburg, South Africa, the question of nature has emerged in their theses topics in interesting and somewhat unexpected ways. I’ve only just started in my new job, and, as a way of quickly getting to know my new students and the ways in which they think/draw/read/explore their immediate built environment, I asked them to ‘name’ their city — Johannesburg. I was fully expecting terms such as, The ‘Disconnected’ City; The ‘Migrant’ City, The ‘Broken’ City, adjectives that have been in vogue in South African urban discourse(s) for many years. Somewhat to my surprise, however, they came back with other adjectives, new ways of describing the spaces and places they inhabit. The ‘Natural’ City; ‘Rehabilitated’ City; ‘Landscape’ City, ‘Greenway’ City, pointing to a fascination (and possibly new affinity) with nature that goes beyond the historical and colonial obsession with land as a way of binding oneself to inconveniently hostile, already-inhabited territories. Of the thirteen projects I’m currently guiding, four stand out, in different ways and for different reasons.

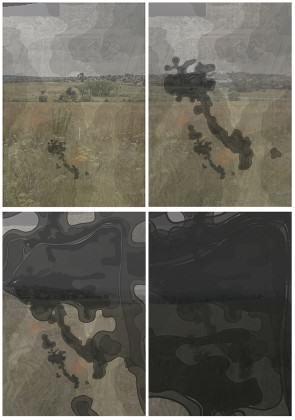

The Frontier City, by Tiffany Melles

A barren ridge in the centre of Johannesburg. A cluster of people dressed in white sit on a rocky outcrop. A man stands, addressing his followers: women on the right and men on the left. Over time, his speaking ceases and the sitting people join together in song, their hands pressed together in a gesture of prayer. A solitary nun, dressed in her full habit, kneels, hands clasped tightly in prayer. Nearby, on the roof of an abandoned building, a line of Muslim men stand bowed over, facing Mecca, reciting the Quran. Clapping and singing can be heard from all around. Amongst the gatherings there are large puddles of wet earth and broken glass, marking areas where prayers have been released. There are numerous ‘frontiers’ — forgotten gaps — in Johannesburg’s urban fabric, empty ‘natural’ landscapes where people gather for different purposes. Some gatherings are religious, some social, some a combination. This dissertation will attempt to describe the narrative and spatial stories of a number of these ‘frontier’ sites, and develop an appropriate architectural response.

Tiffany’s main site — the Wilds — is a 16 hectare nature reserve, adjacent to Houghton, one of Johannesburg’s oldest suburbs. Her project, although in its early stages, attempts to marry the contradictions between religion, ritual, leisure and recreation to suggest an architecture that is neither entirely ‘natural’ nor entirely manmade.

Her drawings, which combine a number of different techniques: mapping, siting, coding, and land-marking, suggest a new relationship between program and site. In an area prized for its ‘wild’ nature, new forms of use and occupation have sprung up outside the city’s formal planning strictures. These ‘traditional’ forms of worship are not bounded and housed in the same way as other major religions: here there is no ‘church’, no altar, no mosque, no temple. The spiritual and natural worlds exist in the same dimension and space, where ritual and use establish the hierarchies of worship: preaching and prayer, hearing and listening, cleansing and purifying.

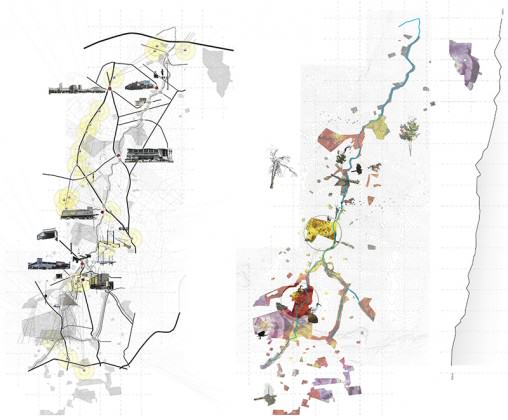

The Connected City, by Zoë Goodbrand

Zoë’s strapline, Reclaiming Johannesburg’s Natural Environment, speaks directly to the issues of ecology, nature and parklands that most of us are already familiar with. What is potentially interesting in her project is the juxtaposition of normative (read: Western) notions of parklands, the management of ‘nature’ by city municipalities for the enjoyment of city dwellers and the potential for ‘other’ cultural readings of nature, leisure and recreation that could influence and shape her chosen site and program. Her reading of the site sits within a traditional Eurocentric perspective:

‘public parks are utilised primarily for recreational use and to provide people with social locations that offer opportunities for them to meet with friends, observe other people and be seen. Crime, a history of spatial segregation and a lack of infrastructure have rendered the area under-utilised and abandoned. It is a sad fact that many Johannesburg residents’ experience of outdoor space and nature is often limited to that which exists in their backyards. People often travel to and from work without ever coming into contact with nature, placing a disproportionate importance on private gardens as a way of connecting people with their natural environment. One possible way to link the domestic ‘garden’ and its somewhat sanitized version of the ‘natural’ world with broader ecological themes, is through ‘linking spaces’, green linkages between home/park/work/local services and the ‘wilds’, of particular importance to suburban dwellers who, in themselves, exist in a twilight state between the ‘real’ urban and the rural.’

‘Humanity currently exists in a dysfunctional relationship with the natural world and auto-bound cities are both symptom and cause of this dysfunction.’

As Johannesburg’s suburban population becomes increasingly reliant on private motor vehicles as a mode of transportation, we enter deeper and deeper into this dysfunctional relationship. This is a result of the fact that middle-class, suburban Johannesburg was created on the assumption that every middle-class household would own a car, with blocks too large and facilities too separated to enable people to walk, replacing pedestrian movement with vehicular movement. In this scenario, it can be argued that the private vehicle is as a major source of social alienation, creating a city of disconnected strangers.

Zoë’s proposal sits at the intersection of these concerns: our growing disconnectedness from our natural environments; the dislocation of the suburb from both nature and the city and the risk of even greater social alienation.

Like Tiffany, her use of the techniques of mapping and coding allow her to grasp, digest and manage the vastness of her site, which stretches almost the length of the city. By identifying infrastructural elements (bridges, power lines, tunnels, roads, malls, leisure facilities) alongside ‘natural’ elements (plants, gardens, views), a conversation starts to emerge between the two worlds: instead of a strip shopping mall, she proposes a garden centre; a drive-in movie theatre that makes use of nature, rather than suppressing it. The speed at which one cycles or walks through a landscape profoundly alters one’s view of it: her careful analysis of surfaces — tarred, rough, smooth, paved, grassy — provides opportunities to stop, savour a view or a scent, take in the city from a distance, see something new/different/’other’.

The Forgotten City, by Gabi Coter

This thesis looks at open landscapes across Johannesburg that were left behind and forgotten within suburban areas of the city as a result of white flight, urban sprawl and the establishments of buffer zones between residential areas. This thesis aims to imbue such forgotten landscapes with dignified means of ‘memory’ and/or ‘remembering. Rietfontein Farm (in Johannesburg) sits like an urban island within the suburban areas of Edenvale, Linksfield and Rembrandtpark. This fifteen hectare site lies unused and forgotten, primarily because of the Sizwe Tropical Diseases Hospital situated in the centre. When the hospital was first opened in 1895, the open land around it was configured as a buffer zone between the ‘unhealthy’ grounds and surrounds of the hospital, and the neighbouring suburbs. Just outside the hospital grounds, a number of cemeteries were created to bury victims of smallpox, tuberculosis and bubonic plague. Although many of these graves are unmarked, it has been established that over 6,000 bodies lie buried within the site’s boundaries in unmarked and unnoticed graves. This site, which has adapted and reinvented itself many times over, can be read as a ‘third’ landscape, following Clements’ description of ‘landscapes having been formed primarily due to the rapid growth of cities and the effects of urban sprawl.’

Gabi’s drawings, which map and explore the site at a number of different scales, see nature as a healing force within the city-scape, not only for its restorative powers in terms of growth and re-growth, but for its ability to protect and prolong memory. Using the notion and programme of a clinic, it is her intention to rehabilitate this third forgotten landscape through sensitive landscape interventions and restore its ecological and cultural dignity.

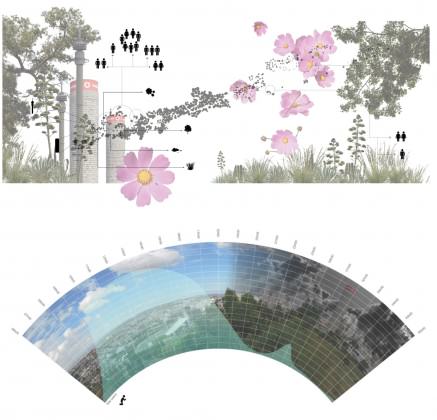

Junkspace City, by Rachel Wilson

‘We no longer live life, we consume it.’

A consumer-driven approach to the economic ‘health’ of a society tends to focus solely on growth (GDP), employment and urbanisation. As a result, ‘softer’ measures of development such as water and natural landscape preservation tend to fall by the wayside. In Africa, this is particularly endemic where ‘progress’ and ‘development’ focus almost exclusively on ‘hard’ data and more nuanced and culturally-sensitive/appropriate responses to the environment are dismissed or under-played. This unbalanced approach to development has led to the destruction and scarring of many urban landscapes which teeter on the brink between potentially productive spaces (in all senses of the word) and perpetual abandonment. These marginalised and often unseemly landscapes are what I call ‘junkspaces’, and are the focus of this year’s investigation, a potential buffer-zone or no-man’s land between spaces of consumerism and extreme urbanisation and ecological preservation.

Rachel’s dissertation explores the breakdown in society between extreme consumerism and the fragile eco-systems of Johannesburg, proposing an Institute of Political Ecology which mediates between the worlds of finance, development and politics, the ‘real’ world of policy and governance, and the ‘natural’ world of ecology, sustainability and landscapes. It’s a challenging, complex architectural brief with the potential to weave together systems, materials, programs and possibly even forms from a number of different spheres. Her ‘Endoxene’ drawings below are a hybrid transplant of Johannesburg into the rural landscapes of Kigali, Rwanda, showing the communication connections that bind diasporic communities together and playing on the notion of the nostalgia for the ‘homeland’ that is often experienced by those who have left home (back again to the notion of ‘roots’, see 1-4 at the beginning of this essay).

Root and Rhizome(s)

7. to root for (verb) to encourage a team or contestant by cheering or applauding enthusiastically. To cheer, cheer on, shout for, applaud, clap, boost, support.

8. rhizome (noun) in botany and dendrology, a rhizome (from Ancient Greek: rhízōma ‘mass of roots’,from rhizóō ‘cause to strike root’)

Embedded (perhaps subconsciously) within these four student projects are complex ideas about ‘landscape’, ‘nature’ and ‘ecology’, particularly in South Africa where conflicting material interests in the ‘natural’ world — from ideas about how and what to farm (subsistence vs. industrial farming practices, for example) to the ‘spoils of nature’ — minerals — which have driven and dominated South Africa’s wealth for centuries — collide. Questions of ownership still dominate the discourse around ‘land’ and ‘landscapes’: who ‘owns’ the land, on whose terms, in whose image, according to whose beliefs and practices? We are accustomed to the idea that culture, social practices and religion are the common fault lines in any given society: what these student projects demonstrate, albeit tentatively, is that ‘nature’ itself is every bit as rich, complex (and, yes, fraught) a belief system as anything and everything else.

The schism between the natural and the man-made, or between ‘nature’ and ‘culture’ (culture being what we do to and with nature), is site-specific and culture-specific, and not universal in any sense. In today’s global, multicultural and highly cosmopolitan urban environments, where radically different views about ‘nature’ often predominate, how do we explain, explore and exploit these differences in ways that hold meaning for us all? (see 7 above). The radical feminist Audre Lorde’s phrase, ‘the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house’ is pertinent: now, more than ever, in societies that are literally ‘made up’ of sometimes contradictory and opposing views, the ability to think outside our normative boxes, disciplines, ways of seeing and working, is not just visionary, it’s required. It’s sometimes said that culture is the sum total of the stories we tell ourselves, about ourselves. For many Africans, whose spiritual, ritual and material connections to the ‘natural’ world run deep, the absence of a sustained, creative and critical discourse around ecology and nature in our exploding urban centres is a dangerous void, one that we will struggle to fill.

Origins. Ancestors. Roots. Rhizomes.

To root for: to cheer, to cheer on, to support and applaud.

Lesley Lokko

Johannesburg

Great text, love the linking of landscape to boundaries…

Would be interesting to read the reference to ancestory & landscape in context of films by Jean Pierre Beloko…

It is great to see theses projects that go beyond the building, which begin to speak more aboot the real spheres of influence that future architects should and need to address in their context. What these projects do in the spatial “healing ” of the the city, speaks of much greater social cultural influence that architects need to exercise in the future- to remain relevant. These projects give architecture and society much hope. The students are in good hands. Well done!