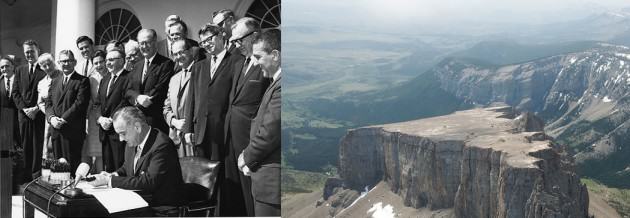

September 2014 marked the 50th anniversary of the signing into United States law of the Wilderness Act. A watershed act and a cornerstone of contemporary environmentalism, it put into place new and important safeguards on the protection and development of some of the nation’s most impressive wild areas.

As we celebrate the accomplishments of this act and the incredible wild and wondrous places it protects, it is timely perhaps to re-consider the concepts of wilderness and nature in our lives, and to consider they ways they will necessarily need to evolve and change in an increasingly urbanized planet.

The Wilderness Act of 1964 contained an essential and oft-repeated definition of wilderness: lands that are “untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain”, and an area “retaining its primeval character and influence, without permanent improvements or human habitation”. The Act created the National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS), and now protects more than 9 million acres, placing important restrictions on road building and development in these areas, and ensuring the preservation of their wilderness qualities and habitat values.

The Act was a remarkable accomplishment, and a ringing endorsement of the value of wild places and the quiet solitude of nature in a modern world. But the Act has also had the unintended consequence of helping to solidify the particular notion that genuine or “authentic” nature is remote, pristine, necessarily large in size, and for the most part absent human beings.

Re-thinking urban wildness

Perhaps on this important anniversary it is time to broaden our view of wilderness, not to deny the value of experiencing remote quietude, but to acknowledge the equally valid experiences of wild nature in and around cities, where most people live.

Much has changed, of course, since 1964 and our knowledge of the history of land and landscapes has grown in some important ways. Book’s like Charles C. Mann’s 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus, for instance, have helped to show the true (and considerable) extent to which native peoples have actually modified the landscapes in which they lived. The long-popular view of the new world as a verdant land, untouched by human hand, has been shown to largely false. There are few places in North America or elsewhere that have not been highly impacted by humans, and thus the very notion of pristineness has come into question.

Equally true, we increasingly recognize the importance of natural areas that are in symbiosis with humans, and understand that any notion of modern environmentalism must include, not exclude humans. There has also been a significant rise in the body of research showing how important access to any contact with nature is our health and happiness. We know that we need that connection, that contact with nature, not just during an occasional holiday or summer vacation, but we need it daily or hourly. We need nature all around us and nature, so the new view holds, necessarily need not be remote or distant, but is often more essential and useful when it is near to where we live and work.

Landscape historian William Cronin helped in the mid-1990s to stimulate new thinking and discussion about what we think of as nature, most importantly in his book Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature. As Cronin says there, “Wilderness gets us into trouble only if we imagine that this experience of wonder and otherness is limited to the remote corners of the planet, or that it somehow depends on pristine landscapes we ourselves do not inhabit”. When talking of cities perhaps wildness is a better word.

The potential for experiencing the wonder and amazement of the natural world is all around us, even in dense cities, and thus we need to embrace a new, expanded view of nature, one that understands that the qualities wildness can be found in many places and spaces that may not fit the usual stereotype.

We must work to overcome an overly purest view of wildness that questions natural views and settings that contain buildings or urban skylines. The experience of urban wildness may be more fleeting, less immersive, than the Wilderness Act envisioned, but better fits the reality of urban life. We need wild places a close walk or bike ride, or a quick transit trip away.

The Wildness of the Nature of Cities

We know, for instance, that there is immense biological diversity in the soil, and in water at a microscopic level. E. O. Wilson has referred to this as “microwildernesses”: “A suburban woodlot is obviously no longer a wilderness for mammals, birds, and trees. But it might be a “microwilderness” for small organisms” (2006, p. 18). We know that there is often remarkable wildness in the diverse world of the many other small things around us, from moths (there are more than 10,000 species of moths in North America, many of which are micro-moths), to lichen, to mushrooms and fungi. Larger green spaces will remain important, of course, but much of this wildness is delivered in the often small, but potent, interstitial spaces of cities.

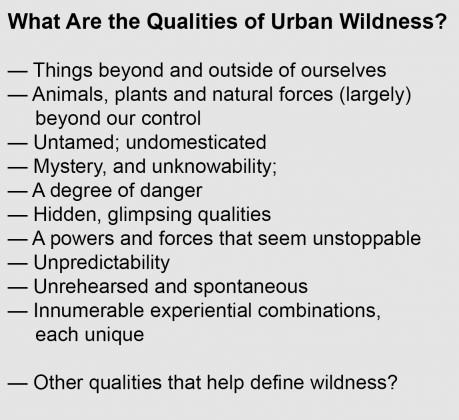

Precisely what constitutes wildness, and what stimulates the feeling or experience of wildness, remains an open question. It is certainly a complex set of conditions, to be sure, but some mix of sense of the immensity of the scale and uncontrollability of forces at work, that it exists without much concern for the human world, and lives and thrives in ways that are, to some considerable degree, mysterious and unknowable even. It is the sense we get from things that seem untamed, undomesticated. Perhaps it is the glimpsing ways in which we see the nature around us—and the largely hidden lives that characterize much of natural world. And it is the fierceness and force of nature often that seems to impart its wildness and demonstrate its untamedness, as with a flooding river or fast creek, or a windstorm or hurricane.

Which is all to say that these qualities of wildness, and the experiences of wildness, need not be restricted to remote “wilderness areas”, areas far away from cities. The experience of wildness, moreover, need not be a solitary experience to be meaningful or beneficial. It can happen even in the presence of many others, for instance when hundreds congregate each fall in Portland, Oregon, to watch the amazing spectacle of thousands of migrating Vaux’s Swifts as they converge on a school chimney to roost for the evening.

We need to replace the perceptual dichotomy that many still carry in our heads between cities and nature. The evolution in our thinking should encompass the new ways in which flora and fauna are evolving and adapting to cities and urbanization, and we’re only now beginning to understand this. Bird species are changing the frequencies of their songs in response to urban and traffic noise, for instance. And increasingly there are examples of “new” forms of nature, what ecologists sometimes call novel ecosystems, unique assemblages of native (and non-native species and habitats, that have formed in and around cities. Perhaps there is need for unplanned ecological spaces in our notions of urban wildness; making room in cities for a sort of ecological improvisation, with sometimes unexpected results. We will need to adjust our ideas about nature to include these ways in which the nature in the future will be different from what we previously have known.

We need to replace the perceptual dichotomy that many still carry in our heads between cities and nature. The evolution in our thinking should encompass the new ways in which flora and fauna are evolving and adapting to cities and urbanization, and we’re only now beginning to understand this. Bird species are changing the frequencies of their songs in response to urban and traffic noise, for instance. And increasingly there are examples of “new” forms of nature, what ecologists sometimes call novel ecosystems, unique assemblages of native (and non-native species and habitats, that have formed in and around cities. Perhaps there is need for unplanned ecological spaces in our notions of urban wildness; making room in cities for a sort of ecological improvisation, with sometimes unexpected results. We will need to adjust our ideas about nature to include these ways in which the nature in the future will be different from what we previously have known.

Part of this urban wildness is on display where formerly developed or human-occupied is, for some period of time, given over or given back to nature. One thinks of the experiments in re-naturalizing in the Emscher Park, in the Ruhr Valley of Germany, or the newer efforts to re-purpose spaces in Berlin, such as the former Templehof Airport (now an urban park larger than Central Park in New York). There is even an organization called “Abandoned Berlin” celebrating the many places, like Spree Park, a former amusement park now, and at least temporarily, given back to nature. Setting aside areas in and around cities for re-naturalizing, or re-wilding, is close to the notion put forth by environmental philosopher Paul Taylor in his classic book Respect for Nature: “rotation” or “taking turns”, he indicates is one method for advancing distributive justice between and among human and non-human species. An urban nature version perhaps of leaving agricultural fields fallow, the longer-scale rotation of some lands in cities offers opportunities for forms of wildness quite different from those imagined by the Wilderness Act.

This opens as well the possibilities of designed wildness in cities. Perhaps a contradiction on some level, architects and urban designers increasingly recognize the need to accommodate some degree of wild nature into the very corpus of buildings and urban structures. University of Buffalo architect Joyce Hwang has been innovating here, experimenting with new human-designed structures to accommodate bats and other urban critters (she has designed a beautiful, prototype bat tower, and a series of hanging bat pods that she calls a Bat Cloud). She is also working on creative new ways of re-imagining building walls and facades that also serve as important urban habitat (“pest walls”, she calls them , in her essay “Constructing Wilderness”). Part of her key goal is to make the wildness visible to urbanites.

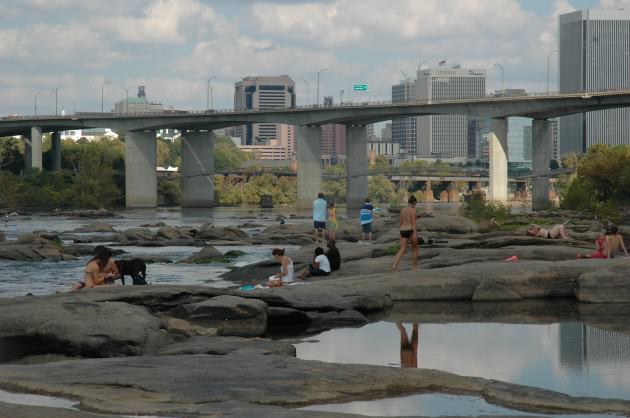

Urban notions of wildness will necessarily entail a hybrid mixing of the built and natural. An emerging example close to my heart (and geographically close), can be seen in Richmond, Virginia, where a wild river ecosystem (the James) interacts with a highly designed and constructed city. It is an unusual but desirable juxtaposing—class five rapids, and a rocky, powerful river in close proximity to where people work, live, walk and recreate, and exhibiting daily the conditions of nature only partially predictable and controllable.

Access to this river wildness has become a key feature of planning for the City of Richmond, and a new Riverfront Master Plan seeks to foster new opportunities for contact. One place where this is already possible is on the Pipeline Trail, a walking trail on top of an actual large pipeline running parallel and in the river itself. Visitors can walk along this trail, a breathtaking experience when water levels are high, and even more breathtaking when the re-assuring handrails disappear from the pipeline. There is a certain feeling of danger here, which may be another dimension to experiencing wildness, and on virtually any day a visceral sense of the power and fury of this majestic river.

And there are many other places along this urban stretch of river where its wildness can be enjoyed. Kayakers run the rapids, bathers and swimmers make cautious forays, kids and families hop from rock to rock in a fascinating kind of archipelago that exists near the northern edges of Belle Isle, all within sight of the tall buildings of downtown Richmond.

On a recent visit with students from my Cities + Nature class, we found a churning river, with abundant Shad (a migratory fish quite important to the history of the river) jumping and swirling in the eddies of the water caught in the corners of foundation walls. Walking on the Pipeline Trail takes you in close proximity to a large heron rookery, and on that day these majestic birds were sunning, and on the look-out for Shad, as was the Osprey flying overhead, all within a few hundred feet of a busy downtown. These experiences are as wild and exhilarating as any that might be in a more remote setting.

Wildness may in some ways challenge the very notion of contemporary urban planning. Some planners will resist the notion that there are things in the urban realm—natural forces, biology, flora and fauna—that are largely beyond our control (a point that David Maddox made in reading an early draft of this article). Yet, as I have suggested there may well need to be modes of urbanism and urban planning that emphasize designed wildness.

How to take this wildness into account in the formal plans and planning processes of cities remains an open question. Not many contemporary urban plans explicitly aspire to wildness, I suspect—and UVA PhD student Julia Triman is currently analyzing city plans to see if this is the case. On the contrary, we should begin to both advocate for and celebrate the many ways in which wildness, and experiences of the wild, can be seen to occur, and can be actively fostered as an important and desirable urban quality.

A desire for a wild city, or places of wildness in the city, should be included in a plan’s statement of goals and vision. Urban plans, moreover, might designate wild corridors, or wild urban zones (the watery edges of the James River in Richmond, for instance), or perhaps areas of planned re-naturalizing or re-generation? In part this would help to cultivate the wild sensibilities we want citizens and residents to bring to these places, and see and appreciate them for the wildness they present, in contexts that may seem surprising.

Tim Beatley

Charlottesville

Note: A shorter version of this essay appeared as Beatley’s Ever Green column, in the October issue of Planning Magazine (published by the American Planning Association).

References

Mann, Charles, 2006. 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus, New York: Vintage.

Wilson, E.O. 2006, The Creation: An Appeal to Save Life on Earth, New York: Norton and Company.

Wonderful piece, many thanks for developing and articulating those thoughts so nicely, Timothy. What a wonderful day out you had with your students, to see spawning Shad, hunting Osprey and herons within such urban proximity! I’m convinced that field trips are essential to ecological design education and training. For our ecological design modules, within the Dept of Landscape at the University of Sheffield, one site we always take students to is an abandoned quarry in the Peak District National Park. The neat lines of the quarried landscape, bordered by rocky uncut crags are juxtaposed with a dense forest of White birch, evenly spaced, same aged, without any undergrowth. It appears designed, and the relict industrial machinery and abandoned grindstones, suggest it has been. Yet the vegetation is clearly self established and dynamic without any human inputs. Thanks again for a great post. Continued success. Truly, Christine