“Because then it becomes a beautiful self-driven machine. Nature driving people driving nature. Where the word is spread and the pride is shared and spread and it spills over (in the community). Everyone wants to feel proud of something that is on their doorstep“.

—Kelvin Cochrane, baker and community-activist,

Bottom Road Sanctuary, Cape Town

This piece sets out to explore whether small-scale civic-led gardening schemes are just feel good stuff or whether they make a contribution to the functioning ecology of our cities.

The simple act of digging your fingers into the soil, pushing a seedling into the ground, nurturing it and watching it grow is a sacred, visceral and beautiful process, which opens the door to a greater respect and sense of awe for nature’s mysteries and treasures. There is no doubt that social gardening initiatives, aside from playing a pivotal role in creating the human connections that help reinforce a sense of community, help to generate biophilia and a greater reverence for and connectedness with nature in cities. These sorts of initiatives assist in integrating urban ecosystems as part of the daily experience of citizens, subsequently aiding in creating a new inclusive way, as opposed to a purely scientific way, of speaking about and carrying out conservation objectives that can include and be understood by the everyday citizen.

The urban ecology literature presents several cases of the importance of the social dimension of these kinds of engagements promoting and supporting sustainable environmental projects and awareness, encouraging social cohesion, and fostering local ecological knowledge. A colleague of ours who works for the Biodiversity Management Branch at the City of Cape Town once noted how humbled and delighted she always is to stumble on pockets of people doing innovative, environmentally-relevant gardening projects in their neighbourhoods. She also noted that these were the best places where urban conservation managers might intervene, where value could be readily added with information on appropriate indigenous plant species or offers of support in kind or through labour, as the energy and enthusiasm of an already-mobilized community is an exciting thing.

However, some conservation managers dismiss small urban patches and civic indigenous gardening projects as nothing more than points of social cohesion and activity on the basis that make no meaningful contribution to greater ecological functioning in the city. We disagree.

The social value of urban gardens is not news. What is less understood, and what drove us into this particular field of enquiry—this research formed part of a Masters dissertation conducted in 2010 by Georgina Avlonitis—was what the ecological spin-offs of small-scale community endeavors in our cities are. Are these just feel-good hotspots or do these small-scale civic projects actually make an ecological contribution of sorts and what are the likely biodiversity outcomes?

We set out to explore this question by picking a spread of sites to examine ecological outcomes along what we saw as a gradient of engagement and an ecological continuum (ranging from relatively degraded sites, to those that have a high conservation status). Our sites included two civic-led indigenous gardening projects, a vacant lot, and two local nature reserves (one of which is a tiny patch of land conserved by default in the middle of one of Cape Town’s oldest horse race tracks). The two civic-led garden projects are the Bottom Road Sanctuary project and the Princess Vlei garden. Bottom Road Sanctuary is a household neighbourhood project which saw the transformation of a wasteland in a low-to-middle income community. Neighbours, inspired by what they saw over the wall in the first garden, which was catalyzed by community-activist Kelvin Cochrane, decided to physically remove the walls separating their front yards to eventually create (in a little over 10 years) what now stands as a magnificent open-access and indigenous community garden on their doorsteps.

The second community garden project is in the same neighborhood, but is a school gardening project on what was previously a wasteland adjacent to the Princess Vlei. This project is younger, being only about six years old, but has a much larger public participation component. Both these projects, while driven by the community, were supported with plants and guidance from the local nature reserve, Rondevlei. The factors driving these gardening projects were informed by a sense of community activism relevant to the post-apartheid urban form, relating to notions of indigeneity, ownership, the ‘good and just city’, and beautification. Our nature reserves were the Kenilworth Racecourse and Rondevlei Nature Reserve. The vacant lot was simply a large empty lot that had no evidence, or any local history, of ever having been developed.

We confined our sites to one original vegetation type, the Cape Flats Sand Fynbos, deemed Cape Town’s most ‘unlucky’ vegetation type as more than 80% has already been transformed and only 1% is statutorily conserved. We measured richness and functional richness among insects and plants (on the basis of the understanding of the causal link between diversity and function) in a series of plots at each site.

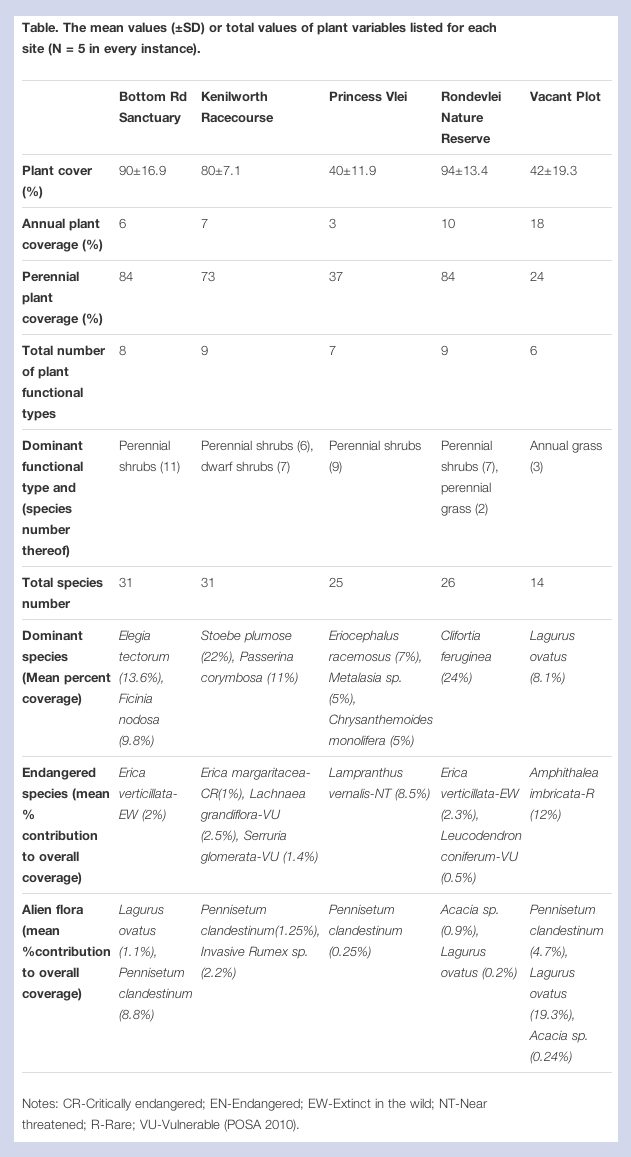

Our key findings, drawing on five 9m2 plots at each site, show a consistent pattern of similar plant cover, functional type diversity, and species richness between the conservation sites and the Bottom Road garden (see the Table at the bottom). The Princess Vlei project lags somewhat, but as a younger project much a kin to the Bottom Road project this is likely to be on a similar trajectory. The Vacant lot has lower plant cover, functional richness and species richness. The Princess Vlei project and the Vacant Lot have some similarities in cover and functional richness, but the Princess Vlei site has far greater species richness and greater perennial cover. The Vacant Lot has the greatest richness and cover of invasive alien plant species.

While we acknowledge that it is difficult to identify causal mechanisms in ecology at the best of times and that the urban context is even more complex where ecologies are produced and modified through social, economic, political and cultural processes, some clear trends are evident. What we see is that total neglect, represented by the vacant lot, results in poor species richness and associated ecological functionality outcomes. Without intervention our vacant lots rapidly deteriorate to the ubiquitous urban patch dominated by a relative monoculture of grass and weedy annual species. The presence of high annual cover suggests a seasonally vulnerable site that will have limited cover in the hot dry summer months rendering it open to erosion. The presence of one rare indigenous species on our vacant lot suggests potential; some remnant gems are waiting to be nurtured back to functioning communities.

Without intervention however, these extant species present nothing more than extinction debt, waiting to slip away into obscurity the same way other indigenous counterparts on this vacant lot must have quietly disappeared years ago. This vacant lot reminds us of the heavy toll of urbanization on our indigenous flora and stands in stark contrast to the outcomes of the civic-led indigenous gardening projects where the role of informed activism presents astoundingly different outcomes.

The two gardening projects show a sound trajectory towards sites that have plant richness and functionality similar to the two conservation sites. A correspondence analysis exploring species composition and cover in space show just the trajectory we anticipated with the vacant lot an isolated outlier, and the two gardening projects ‘pulling towards’ the conservation areas, with the older and more established Bottom Road garden lining up more closely with the conservation areas than the younger Princess Vlei garden. There are sampling issues around plot and plant size and associated age, but generally what is evident is that concerned and informed social engagement can see the construction of healthy patches of indigenous garden akin to adjacent conservation areas. In every instance the need to monitor and manage invasive alien plant species is evident. This is a common urban problem that requires relentless attention.

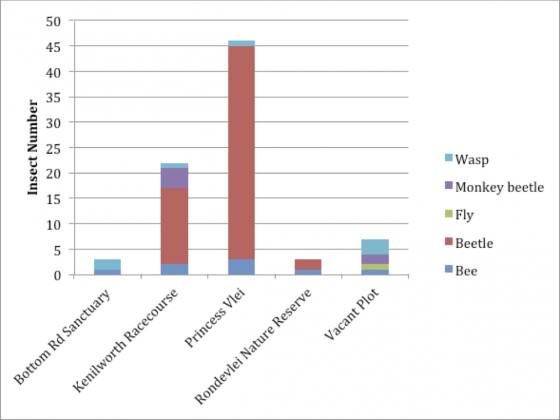

Consideration of the insect morpho-species richness at each site presents a potentially less clear picture. The Princess Vlei site has the greatest volumes of insects, followed by Kenilworth Racecourse (see the Table). Aside from these two sites the numbers of insects trapped are very low. The Vacant Lot, while low in actual numbers, has a surprising richness in functional diversity. It is possible the results are confounded by the competitive role of actual flowers resulting in lower insect trapping rates in the more diverse and densely vegetated conservation areas. This could also account for the high trapping rate at Princess Vlei which is less well vegetated as a more recently initiated project. The vacant lot presents relatively high morpho-species richness, and this can be attributed to the abundance of annual flowering species where there would be no floral support at this site outside of the spring flowering season. While perhaps less compelling when compared to each other, when considered together in the broader context of the urban setting, and in keeping with previous studies, these vegetated patches contribute to the matrix in providing a diversity and functional diversity of insect morpho-species. The loss of pollinators as an outcome of urban fragmentation is well documented. In the Cape it is believed as much as 83% of our flora is insect pollinated. Without the simultaneous return of pollinators any patch of indigenous vegetation ultimately faces extinction.

There are some conservation managers who would argue that this kind of endeavor, without ever being self-sustaining without fire or spontaneous propagation (certainly for those fire-driven species prevalent in the Cape Flora), can never be counted as a true contribution to conservation across the city.

There are some conservation managers who would argue that this kind of endeavor, without ever being self-sustaining without fire or spontaneous propagation (certainly for those fire-driven species prevalent in the Cape Flora), can never be counted as a true contribution to conservation across the city.

We feel they are wrong. Surely any effort that provides even small patches of indigenous vegetation with appropriate biodiversity elements and functional richness to the broader matrix of indigenous species across the city and fosters social engagement with nature makes a contribution to the conservation mandate of the city? So while these patches may not achieve what a large-scale conservation endeavour would in terms of sustainability they do have elements of ecological functionality that make a worthy contribution, akin to Timon McPhearson and Victoria Marshall’s notion of the relevance of the micro-urban.

Here we see how socially-informed goals meet those of biodiversity conservation to produce excellent social and ecological outcomes. Local school children have learnt about indigenous plants and experienced the joy of planting, residents have access to a biodiversity-rich public space akin to the City’s Botanical Garden, the gaps in the urban matrix are filling up with plants that can share pollinators and pollen with adjacent conservation areas, and populations of threatened species have been expanded. Our work supports the view that these pockets of civic-engagement present a key opportunity to both restore nature and build respect and an infectious sense of community pride for what is growing ‘on their doorsteps’ with both social and ecological gains.

Georgina Avlonitis and Pippin Anderson

Cape Town

about the writer

Pippin Anderson

Pippin Anderson, a lecturer at the University of Cape Town, is an African urban ecologist who enjoys the untidiness of cities where society and nature must thrive together. FULL BIO

“[O]ur people can’t afford to go to Kirstenbosch. […] No, and why should they, is the question mark I ask (sic). I’ve always said to them we need to create more Kirstenbosches. Don’t come tell me there’s Kirstenbosch. […] We need to bring that people or the reserves closer to the people. Let them interact and let them find that peace and tranquillity. You know, that has been my fight. Has been from the day we started at… Bottom Road, like I’ve always said to you, it’s only the alpha; it’s not the omega of things.”

https://depts.washington.edu/urbdpphd/symposium/Ernstson4.pdf

Hi, thanks for this piece. What is the approximate land area of each of the places that you looked at?