In October 2014, we had a great opportunity to explore different green areas of several Chinese cities within the project “Sustainable green infrastructure in urban-rural areas of China based on eco-civilization,” which was sponsored by the Chinese Government. It was particularly interesting to see different types of greenery that reflects the development of planning structure in Chinese cities.

Classic Chinese private gardens (scholar and imperial gardens) and scenic spots (specially chosen for their scenic natural landscapes) were the dominant type of green space in Chinese cities for almost 2000 years. These gardens were based on the philosophical canons of harmony and beauty (Taoism, Confucianism and Buddhism).

European public elements of green spaces, such as lawns and flowerbeds, were introduced to China by foreign missionaries during the First Opium War (1839-1842). After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, some remnants of colonial gardens were transformed into public parks for the local inhabitants. In the 1950s, as a result of the “Learning from the Soviet Union” policy, public, multifunctional parks (similar to the USSR’s concept of Parks of Recreation and Culture) became an integral feature of greenspaces in China.

Since the Chinese Economic Reform in 1978, the use of Western forms for green areas has sped up. Governmental officials had a chance to go abroad and rediscover European Renaissance-Baroque styles, followed by English as well as Modernist styles of landscape architecture. They “fell in love” with manicured lawns and colorful flowerbeds. Finally, when China became a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO), it was included in the process of globalization and globalized landscapes arrived to China.

However, this influx did not take into consideration the different climatic conditions or local cultural traditions. Well-mown lawns together with huge plazas, scattered broad leaved trees and regular flower beds became a symbol of success of the Chinese market economy model. Nobody was embarrassed by the high maintenance costs and low environmental value of such new, placeless urban landscapes.

However, increasing densification, traffic problems, and air pollution forced Chinese landscape architects to start the process of searching for local identity of place and new sustainable models for urban development.

Nowadays, design for urban green areas is done mostly by Chinese private architectural or landscape architectural firms as well as by special planning municipal institutions. In some cases, foreign landscape firms and consultants are also involved in the design and planning stages, especially in large-scale projects such as the Olympic Park in Beijing.

One of the most common types of green areas in Chinese cities is the public park. We were pleasantly surprised to see some principles of Feng shui in the overall design schemes of such parks (orientation, axis etc.). Traditional Chinese garden elements such as rocks, water bodies, classic architecture in Chinese style (pavilions, winding corridors, pagodas and bridges), and paving with stones are actively included in the latest public parks.

However, even these kinds of references to Chinese character are in some cases purely decorative and have lost the spiritual meaningfulness they would have held in Chinese classical gardens. Still, some carving stones mimic the original, very important masterpieces of Chinese calligraphy and provide historic information about the site. We were impressed by the very active use of public parks spaces by people during the weekdays and on holidays.

Green areas inside living neighborhoods (multifamily houses of 4-12 floors). The availability of green areas is varied. From a very limited amount in the living quarters of the 1970-1980s, such spaces grew to a quite reasonable size in the 1990s, and in the 2000s-2010s came to include the greenery of bigger inner yards. In such areas, there is a clear tendency to turning away from productive green areas (no lawns) to more decorative pre-designed areas with standardized lawns, hedges, topiary shrubs, and some ground covers.

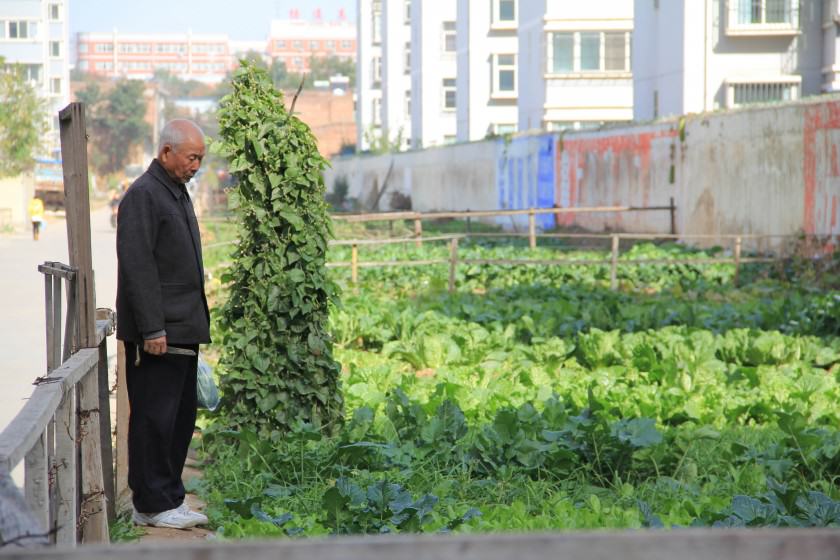

However, even in the most recent neighborhoods (established in 2012-2014) people have turned some of these lawns into community gardens. Many urban communities have a specially designated urban agriculture area within their neighborhood. We connected this phenomenon to the agricultural past of people who have left their countryside farms and moved, seeking a better life in the city.

We found a limited number of tree species used for landscape design in Chinese cities. Monocultures—for example, rows of one tree species—are the rule rather than the exception. A “prefabricated” design palette with open lawns, trimmed bushes, and scattered trees landscapes reminded us of classical Western patterns. Famous English Landscape designer Capability Brown would be very pleased seeing such fruitful results of his ideas on Chinese soil. Since the 1990s, China has turned towards using more global plant material.

Suprisingly for us, we were able to identify quite a few Chinese species. These plants, including Koelreuteria paniculata, Gingko biloba, Lagerstroemia indica, Osmanthus fragrans, and Sophora japonica, were also included in the global “pool” of plants for modern urban landscapes and probably date from the late 1990s. They are used in many countries around the world.

We identified one uniquely Chinese type of urban green area—urban nursery plantations for the growing and sale of plant material. Commercial growing of this type fulfills an important ecosystem services in cities. Compared to Western European countries that principally use global nurseries (from a few particular countries specialized in producing plant material), today China has its own local plant nursery market.

Street tree design is also standardized with a tendency to monoculture. Importantly, this particular type of green area plays a very significant role in Chinese cities because of high levels of urban air pollution. The traditional grandeur of formal planning structure in cities such as Xi’an illustrates the key role of the plazas in the front of historic monuments and administrative buildings. Here lawns and annual flowerbeds cover tremendous spaces. The management of such places is the most intensive and is thus incredibly expansive. There are also some surrounding native forests that are used as public parks.

In a new multifamily neighborhood in Jinan, surrounding forest (on hills with Platycladus orientalis) is used as a neighborhood park. New pathways and traditional pavilions are arranged following canons of classic Chinese parks. Local rocks are used in the construction of the park and in inner green areas. Here, the landscape architect tried to have identity of place by using local material. Local people influenced the choice of plant material so the plant list is a bit different from the one that we have earlier described.

“Gated” community phenomenon

We found the existence of “gated,” highly secured and walled urban communities to be a real surprise considering that before the 1990s, most of the urban green spaces in residential areas (next to homes) were accessible to all people from different areas. According to Chinese colleagues, this gated community phenomenon related to the change of society towards a more individualistic market economy. Other authors argued that this phenomenon is closely related to the old tradition of people living as one family unit separated from busy street life. We observed especially strict control related to these communities in the most recently-developed, rich neighborhood-villa areas.

In recent years as a result of searching for new sustainable solutions, the green roof concept is also becoming quite fashionable. There are still not many green roofs, and the most dominant form is the intensive green roof located on high-rise buildings in dense downtowns. Such roofs no doubt provide several ecosystem services, but they are expensive to manage and maintain. According to landscape architecture practitioners, this is becoming a restrictive factor for mass use of green roofs in China.

- Established in 2009-2011

- Intensive green roof on the top of the building belonging to Real Estate Corporation

- 7000 m2, structure: roof drainage, sand 30 cm and 80 cm of soil

- Big area of lawns. Maintenance of lawns is 50% from whole green roof maintenance. 7 yuan per m2 for lawn maintenance. In summer: every 10 days need mowing. Main argument of having lawn: it’s “cooling” effect (compare to hard surfaces) and absence of appropriate ground covers.

One of the main functions of all green areas in Chinese cities is reduction of air pollution. Today, even a small green area is a very valuable contributor to the physical and spiritual health of Chinese cities.

What we can also conclude from the observation of existing Chinese green areas is that there is a necessity of exchanging good experiences dealing with green areas from Western perspective as well as successful case studies developed by Chinese landscape architects.

We call for creating more hybrid approach emerging positive western and eastern experience.

Maria Ignatieva, Na Xiu and Fengping Yang

Uppsala

about the writer

Na Xiu

Na Xiu, landscape architect and PhD student in Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala. Interested in how green and blue spaces in cities can be strongly connected, landscape history and theory in Scandinavia and China.

about the writer

Fengping Yang

Born in China, Fengping Yang is a PhD student in Landscape Architecture at department of Urban and Rural development in Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU).

fabulous china

all that green within the city…